Abstract

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignancy of the skeleton and is prevalent in children and adolescents. Survival rates are poor and have remained stagnant due to chemoresistance and the high propensity to form lung metastases. In this study, we used in vivo transgenic models of c-fos oncogene-induced osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma in addition to c-Fos-inducible systems in vitro to investigate downstream signaling pathways that regulate osteosarcoma growth and metastasis. Fgfr1 was identified as a novel c-Fos/AP-1 regulated gene. Induction of c-Fos in vitro in osteoblasts and chondroblasts caused an increase in Fgfr1 RNA and FGFR1 protein expression levels that resulted in increased and sustained activation of MAPKs, morphological transformation and increased anchorage-independent growth in response to FGF2 ligand treatment. High levels of FGFR1 protein and activated pFRS2α signalling were observed in murine and human osteosarcomas. Pharmacological inhibition of FGFR1 signalling blocked MAPK activation and colony growth of osteosarcoma cells in vitro. Orthotopic injection in vivo of FGFR1 silenced osteosarcoma cells caused a marked 2- to 5-fold decrease in spontaneous lung metastases. Similarly, inhibition of FGFR signalling in vivo with the small molecule inhibitor AZD4547 markedly reduced the number and size of metastatic nodules. Thus, deregulated FGFR signalling plays an important role in osteoblast transformation and osteosarcoma formation and regulates the development of lung metastases. Our findings support the development of anti-FGFR inhibitors as potential antimetastatic therapy.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, metastasis, c-Fos/AP-1, FGFR, tyrosine kinase, AZD4547

INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive mesenchymal tumor and the most common primary malignancy of the skeleton, occurring primarily in children and young adults. Despite advances in combined adjuvant chemotherapy and limb-sparing surgery, the 5-year survival rate has not improved in the past decade and has reached a plateau of 60-70%1,2. Resistance to chemotherapy and a high propensity to form lung metastases represent the most significant indicators associated with overall low survival. The causes of osteosarcoma are not known, although there is clear predisposition to germline mutations in the pRb and p53 tumor suppressor genes, although these account for only a small subset of tumors3. Correlations also exist with some somatic mutations, including overexpression of oncogenes such as c-Met and c-Myc4-6, and in particular in c-Fos which is expressed in a significant number of osteosarcomas7,8. Genes involved in migration and metastasis, such as ezrin, podoplanin and S100A49-11 have been implicated, however, the mechanisms of metastasis are not clear. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that trigger both the onset as well as its metastatic development are required in order to develop suitable targeted molecular therapies.

Genetically modified mouse models have been informative in understanding the pathogenesis of osteosarcoma3. We have previously demonstrated that transgenic mice overexpressing the c-fos proto-oncogene postnatally develop osteosarcomas with 100% penetrance12. c-Fos is a member of the AP-1 family of transcription factors, containing c-Fos (FosB, Fra-1, Fra-2), c-Jun (JunB, JunD) and ATF (ATF-2, ATF-3, ATF-4 and ATFa) family members13. c-Fos targets cells of the osteoblast lineage for transformation and c-Fos-dependent tumor formation can be modified by additional genetic modification of the c-Fos dimerisation partner, c-Jun14 or the upstream regulatory kinase, Rsk-215. Chondrogenic cells are also targets for c-Fos-induced transformation as transgene overexpression during embryogenesis in chimaeric mice transforms chondrogenic cells leading to a high frequency of chondrosarcomas16. In both models of skeletal neoplasia, the transformation of osteogenic and chondrogenic cells is unique to c-Fos, as gain- or loss-of-function of any other AP-1 family member fails to induce bone or cartilage tumors, despite high expression levels17.

The downstream pathways induced by c-Fos activation and their contribution to tumorigenesis and metastasis are poorly understood. We have previously demonstrated overexpression of the cell cycle regulators cyclins D1, E and CDKs 2, 4 and 6 in c-Fos transgenic osteosarcomas, and specific induction of c-Fos in tetracycline-regulatable osteoblastic and chondroblastic cell lines affected cell cycle progression and differentiation18,19. Taking advantage of the c-Fos-inducible osteoblast and chondrocyte cell lines we have previously screened a number of candidate genes and have identified Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 (FGFR1) as a potential target. FGFRs (FGFR1-4) are members of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family that trigger intracellular signalling cascades that classically involve the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways, but also include PLCγ, Cbl and STAT pathways20,21. FGF/FGFR signalling has a well-established role in the differentiation and growth control of osteoblasts and chondroblasts22,23, and germline mutations in FGFRs cause many developmental skeletal disorders such as craniosynostoses and chondrodysplasias24,25. In this study, we have characterised FGFR1 signalling in the context of c-Fos oncogene induction in osteoblasts and chondrocytes and have identified a role for FGF/FGFR signalling in osteosarcoma cell metastasis.

RESULTS

Deregulated c-Fos expression increases FGFR1 levels in osteoblasts and chondrocytes

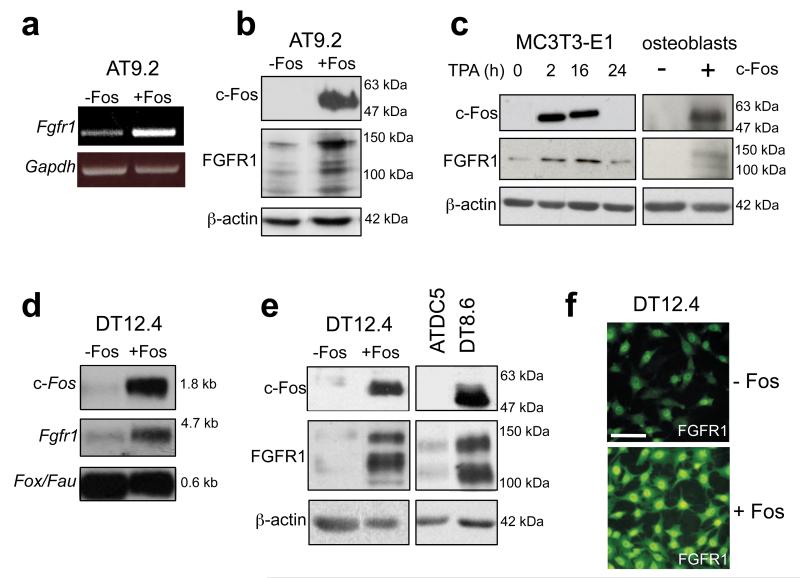

We used the osteoblastic AT9.2 and chondroblastic DT12.4 clonal cell lines which harbor a tetracycline-regulatable c-fos transgene19,26 to investigate potential c-Fos target genes. Withdrawal of tetracycline in AT9.2 osteoblasts stimulated the induction of Fgfr1 RNA and FGFR1 protein that corresponded with c-Fos induction (Figures 1a and b). The correlation with c-Fos expression was verified by incubation of the osteoblastic parental cell line MC3T3-E1 with the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), which resulted in the rapid induction of c-Fos protein within 2h of treatment, and a concomitant increase in FGFR1 protein (Figure 1c). In addition, overexpression of c-Fos by transient transfection in primary mouse osteoblasts resulted in increased FGFR1 protein expression (Figure 1c). A similar induction was observed in the c-fos-inducible DT12.4 chondrocyte cell line, where Fgfr1 RNA (Figure 1d) and FGFR1 protein (Figure 1e) were upregulated following tetracycline withdrawal and c-Fos induction. FGFR1 expression in an additional chondrocyte clone, DT8.6, which constitutively overexpresses c-Fos26, was also increased compared to wild-type parental ATDC5 cells (Figure 1e). Finally, immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the c-Fos-dependent increase in FGFR1 protein, which interestingly showed additional prominent nuclear expression in these cells (Figure 1f). These findings suggest that Fgfr1 is a potential c-Fos/AP-1 target gene in chondroblastic and osteoblastic cells. To assess c-Fos binding to the Fgfr1 promoter, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed which showed increased recruitment of c-Fos to the Fgfr1 promoter which contains AP-1 sites (Supplementary Figure S1), consistent with Fgfr1 being a direct c-Fos target.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of c-Fos in osteoblasts and chondrocytes stimulates FGFR1 expression. (a) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Fgfr1, and (b) Western blot analysis of c-Fos and FGFR1 protein in tetracycline-inducible AT9.2 osteoblasts following 48h c-Fos induction. (c) Western blot analysis of c-Fos and FGFR1 expression in MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts following induction of endogenous c-Fos by TPA, and in primary mouse osteoblasts after transient overexpression of c-Fos. (d) Northern blot analysis of c-Fos and Fgfr1 expression in tetracycline-inducible DT12.4 chondrocytes following c-Fos induction. (e) Western blot analysis in DT12.4 cells showing increased FGFR1 expression in DT12.4 cells after c-Fos induction and in the constitutively c-Fos-overexpressing ATDC5 subclone, DT8.6. (f) Immunofluorescence analysis showing increased FGFR1 staining in DT12.4 cells after c-Fos induction. Bar, 100μm. Housekeeping genes fox/fau, gapdh and β-Actin were used as controls for RNA and protein analyses as indicated.

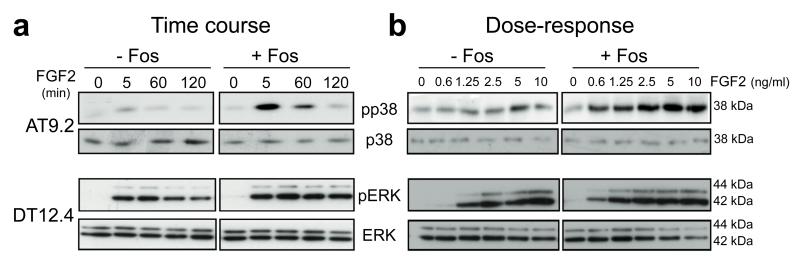

Increased MAPK activation by FGF in c-Fos-overexpressing cells

We next addressed whether the increase in FGFR1 levels resulted in enhanced responsiveness of the cells to FGF ligand stimulation. Time course experiments in AT9.2 osteoblasts indicated an increase in p38 phosphorylation in response to FGF2 following c-Fos induction compared to uninduced cells at 5-60 minutes post-incubation (Figure 2a). No significant effects on pERK and pJNK were observed in this cell line (Supplementary Figure S2a). Induction of c-Fos in DT12.4 chondrocytes led to an enhanced pERK phosophorylation compared to control cells and levels were sustained over a 120-minute period (Figure 2a). Phosphorylation of p38 was only marginally enhanced in this cell line and no effects on pJNK were notable (Supplementary Figure S2b). Moreover, dose-response analyses in AT9.2 and DT12.4 cells showed that increasing doses of FGF2 led to a dose-dependent upregulation of pp38 and pERK, respectively, and this was markedly enhanced following c-Fos induction, particularly at very low doses of FGF2 (Figure 2b). Taken together, these results suggest that FGF stimulation of osteoblastic and chondroblastic cell lines leads to an enhanced and sustained MAPK activation in the context of c-Fos overexpression in a time- and dose-dependent manner, an activity associated with cellular transformation.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of c-Fos in osteoblasts and chondrocytes stimulates FGF2-dependent MAPK activation. (a) Western blot time course and (b) dose-response analyses of p38 and pERK phosphorylation in response to FGF2 (10ng/ml) in AT9.2 osteoblasts and DT12.4 chondrocytes after 48h c-Fos induction. Total p38 and ERK were used as controls for RNA and protein analyses as indicated.

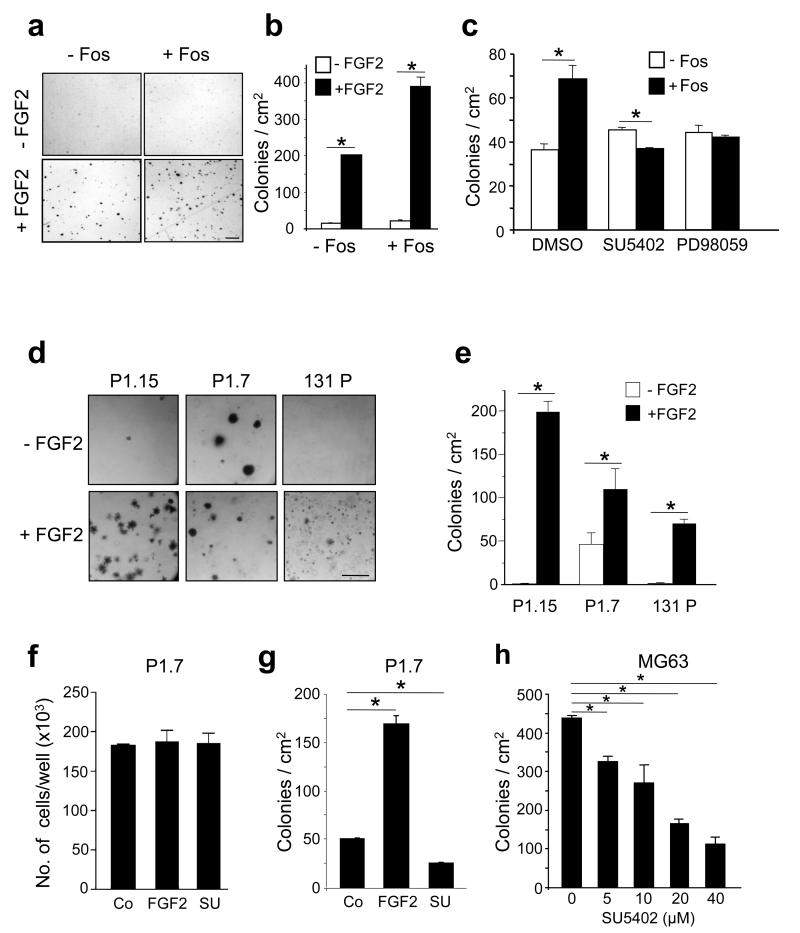

FGF2-induced anchorage-independent colony growth is enhanced by c-Fos induction

To study the functional consequences of FGF treatment, we performed anchorage-independent growth assays in soft agar. Incubation of DT12.4 cells with FGF2 led to an increase in soft agar colony growth and this was significantly enhanced 2-fold following c-Fos induction (Figures 3a and b). The c-Fos-dependent increase in colony number was inhibited by pretreatment with the small molecule FGFR inhibitor, SU5402, as well as with the MEK inhibitor PD98059, whereas no changes were observed in un-induced cells (Figure 3c). Further, treatment of cells with FGF2 caused a morphological change in adherent cells, which was enhanced by c-Fos induction (Supplementary Figure S3a). These morphological changes were prevented by pretreatment with the FGFR inhibitor, SU5402 (Supplementary Figure S3b). Long term cultures continued to show loss of contact inhibition and formation of transformed foci in the presence of both c-Fos and FGF2 (Supplementary Figure S3c). These results suggest that the transforming potential c-Fos in vitro is promoted by the FGF signalling pathway, and this involves FGFR activation and downstream MAPK signalling.

Figure 3.

The role of FGF2 and c-Fos in the regulation of anchorage-independent growth. (a) Representative photomicrographs and (b) quantification of soft agar colonies formed from DT12.4 cells cultured in the presence of tetracycline (−Fos) or absence of tetracycline (+Fos) showing increased colony number in c-Fos overexpressing cells with FGF2 treatment (10ng/ml). (c) Quantification of the number of FGF2-stimulated colonies in the absence or presence of c-Fos overexpression pre-treated with DMSO (control), or inhibitors of FGFR (20μM SU5402) or MEK (20μM PD98059) signalling. (d) Representative images and (e) quantification of anchorage-independent colonies from three c-Fos transgenic osteosarcoma cell lines, P1.15, P1.7, 131 P, in the absence and presence of FGF2 (10ng/ml). (f) Effects of FGF2 (10ng/ml) and SU5402 (SU; 20μM) on P1.7 cell number after monolayer culture, and (g) quantification of the number of soft agar colonies from P1.7 cells in the absence or presence of FGF2 (10ng/ml) or SU5402 (SU; 20μM) as indicated. (h) Dose-dependent inhibition of anchorage-independent colony growth of MG63 human osteosarcoma cells with the FGFR1 inhibitor, SU5402. The data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples. * p < 0.05 vs respective controls. Bars, a: 200μm; d: 400μm.

The functional consequences of altered FGFR1 signalling were next analysed in osteosarcoma cell lines derived from c-Fos transgenic tumours that constitutively express the c-fos transgene and form osteosarcomas as xenografts in syngeneic mice12. FGF2 treatment of three independent cell lines led to an increase in anchorage-independent growth compared to untreated cells, and the P1.15 cell line in particular showed the most robust response to FGF2 (Figures 3d and e). Interestingly, cell number was not affected by FGF2 treatment in monolayer adherent cultures (Figure 3f). Treatment with the FGFR inhibitor SU5402 alone prevented the number of basal soft agar colonies in c-Fos-transformed osteosarcoma cells, as well as in human osteosarcoma cells (Figures 3g and h). These data support the notion that FGFR1 signalling is required for osteosarcoma cell growth, specifically in an anchorage-independent context.

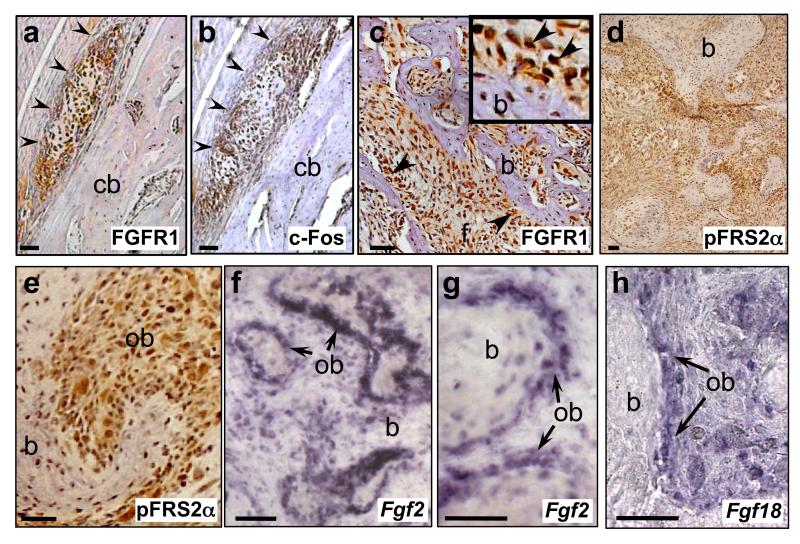

High expression of FGFR1 in vivo in c-Fos-induced murine and human osteosarcoma

We next investigated the expression of FGFR1 and the potential role of activated FGFR signalling in an in vivo context in c-Fos transgenic osteosarcomas. Immunohistochemical analysis in early neoplastic lesions that formed shortly after c-Fos transgene expression (eg. Supplementary Figure 4a) showed high FGFR1 expression that was co-expressed with c-Fos protein (Figures 4a and b). Strong immunoreactivity for FGFR1 protein was maintained up to late-stage tumours and this high expression was particularly notable in transformed osteoblasts lining neoplastic bone, with some osteoblasts showing strong nuclear FGFR1 expression, as well as in the less-differentiated fibrous tumour stroma (Figure 4c; Supplementary Figures 4b and c). Further immunohistochemical analysis of pFRS2α, a docking protein that is essential for FGFR signalling showed similarly high levels of pFRS2α protein in transformed osteoblasts lining neoplastic bone, including some with apparent nuclear localisation (Figures 4d and e). High expression of the FGF ligands, Fgf2 and Fgf18, were also demonstrated in transformed osteoblasts of late-stage tumours (Figures 4f-h), further suggesting activated FGFR signalling. The timing of FGF ligand/receptor expression was consistent with the increased proliferative index during osteosarcoma formation as defined by in vivo BrdU labeling of tumour cells (Supplementary Figures 4d and e). Finally, a correlation between FGFR1 and c-Fos expression was also observed in c-Fos chimaeric mouse chondrosarcomas16, with high levels of FGFR1 in differentiated chondrocytes that also expressed the c-Fos transgene (Supplementary Figures 4f and g).

Figure 4.

Expression of FGF/FGFR signalling components in c-Fos-transgenic mouse osteosarcomas and human tissue microarrays (TMA). (a-e) Immunohistochemical analysis of FGFR1, c-Fos and pFRS2α proteins as indicated, in early osteosarcoma lesions (a,b, arrowheads) arising adjacent to a femoral cortical bone surface (cb), as well as in late-stage c-Fos transgenic osteosarcomas (c-e) (see also Supplementary Figures 4a-c). FGFR1 (c) and pFRS2α (e) immunoreactive cells, including nuclear localisation, are observed in transformed osteoblasts (ob) lining neoplastic bone (b) (arrows, inset in (c)) as well as in fibrous areas (f). RNA in situ hybridisation for Fgf2 (f,g) and Fgf18 (h) expression in late-stage c-Fos transgenic tumours, showing high levels of FGF ligands in transformed osteoblasts (ob).

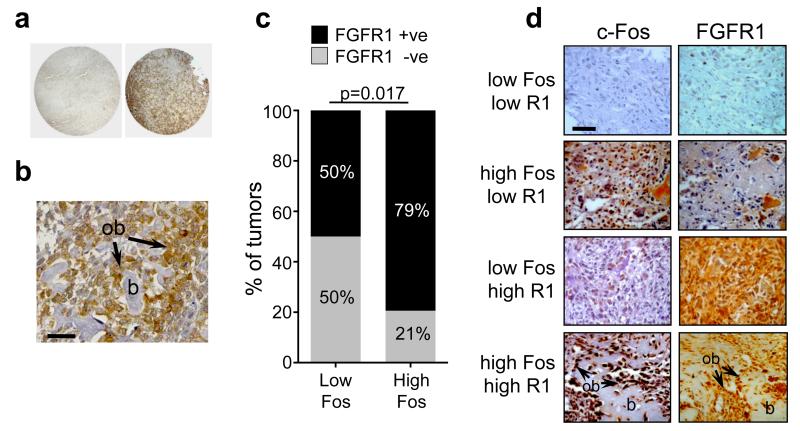

To establish whether FGFR1 might be involved in human osteosarcomas we next investigated FGFR1 protein expression in tumour samples using tissue microarrays (TMAs). Overall, from a total of 86 samples, a high proportion of tumours showed positive immunoreactivity for FGFR1 protein, and particularly relevant was the high expression in transformed osteoblasts within the tumour samples (Figures 5a and b). Semi-quantitative analysis suggested that 64/86 (74%) of samples demonstrated positive immunoreactivity for FGFR1 expression, and of those, 53/64 (83%) were classified as expressing moderate to high levels of FGFR1 (Table 1a). Because of the link existing between FGFR1 and c-Fos in transgenic mice, we also investigated whether a similar association was evident in human osteosarcomas. Parallel TMAs were also assessed for c-Fos expression, and consistent with the observations in mouse transgenic tumours, there was a good correlation between c-Fos and FGFR1 expression. From a total of 86 tumours, 68/86 (79%) expressed high levels of c-Fos, and of those, 54/68 (79%) also expressed FGFR1 (Table 1a). Of the tumours expressing low levels of c-Fos (18/86), 9/18 (50%) also expressed FGFR1 (Table 1a; Figure 5c). Overall, the highest proportion (~52%) of samples expressed high levels of both c-Fos and FGFR1, whereas only few tumours (~12%) expressed low levels of both c-Fos and FGFR1 (Table 1b, Figure 5d). Expression of c-Fos and FGFR1 was also frequently noted in osteoblastic cells (Figure 5b). Taken together, high expression of FGFR1 in osteosarcomas is detected in early stages of osteosarcoma pathogenesis, and this is maintained throughout tumour growth with high constitutive expression of FGF ligands and active FGFR/pFRS2α signalling in the tumours.

Figure 5.

(a) Representative human TMA tumour samples showing negative (left) and positive (right) FGFR1 protein expression by immunohistochemistry. (b) Representative osteosarcoma biopsy showing high FGFR1 expression also localised to transformed osteoblasts (ob) lining bone (b). (c) Quantification of percentage of tumours that express low or high c-Fos protein, and are either FGFR1-negative or FGFR1-positive. The data correspond to raw data presented in Table 1b (bottom panel). p=0.017; Fischer’s exact test. (d) Representative histological samples of c-Fos and FGFR1 protein staining combinations as indicated. High expression of both c-Fos and FGFR1 are also observed in osteoblasts (ob) lining neoplastic bone (b). Bars, 50μm.

Table 1.

(a) Top panel: Semi-quantitative analysis of FGFR1 and c-Fos expression showing the percentage of total samples (n=86) that exhibit negative or positive staining (see also Figure 5a). The total FGFR1-positive cells are further subdivided into low vs moderate-high expression. Bottom panel: The proportion of FGFR1 negative and positive samples that segregate with c-Fos high and low expression. (b) Semi-quantitative analysis following c-Fos and FGFR1 immunohistochemistry showing the percentage of all samples that are expressing the indicated levels of c- Fos and FGFR1 protein (see also Figure 5d). Semi-quantitative analysis was performed as described in the Methods.

| a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=86) |

FGFR1 negative 22/86 (26%) |

FGFR1 positive 64/86 (74%) |

|

|

Low: 11/64 (17%) |

Moderate-High: 53/64 (83%) |

||

|

Fos high 68/86 (79%) |

FGFR1 negative 14/68 (21%) |

FGFR1 positive 54/68 (79%) |

|

|

Fos low 18/86 (21%) |

FGFR1 negative 9/18 (50%) |

FGFR1 positive 9/18 (50%) |

|

| b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fos low

FGFR1 low |

Fos low

FGFR1 high |

Fos high

FGFR1 low |

Fos high

FGFR1 high |

|

| Total (n=86) | 10/86 (12%) | 8/86 (9%) | 23/86 (27%) | 45/86 (52%) |

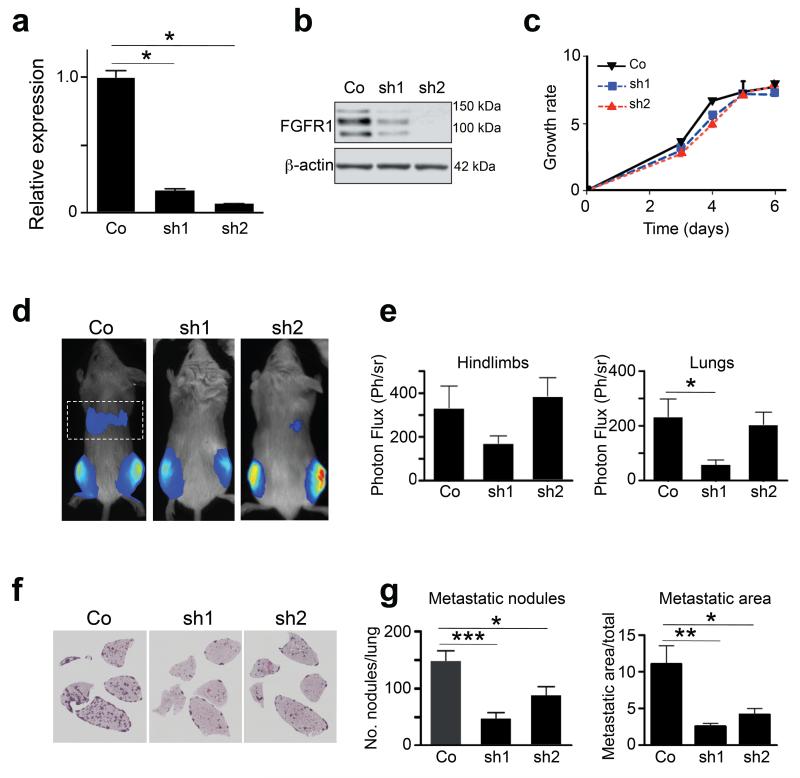

Genetic silencing of FGFR signalling inhibits osteosarcoma metastasis in vivo

Osteosarcoma cells have a high propensity for forming lung metastases, and c-Fos transgenic cells spontaneously metastasise to the lungs upon intratibial injection. We therefore used a well-established in vivo xenograft model to test whether FGFR1 signalling can regulate metastatic behavior of c-Fos-transformed osteosarcoma cells. To this end, we generated two independent lentivirally-transduced shRNA pools (sh1, sh2) targeting different Fgfr1 sequences in P1.15 cells. Both sh1 and sh2 clones showed significant decreases in Fgfr1 RNA levels and FGFR1 protein compared to mock-infected control cells (Figures 6a and b). Growth curve analysis of both silenced clones showed that knockdown of FGFR1 had no effects on cell number compared control-transduced cells (Figure 6c), which was similar to pharmacological inhibition of FGFR1 (Figure 3f). Orthotopic injection of mock-infected P1.15 cells into immunocompromised mice resulted in marked lung metastatic activity 14 days after intratibial injection. However, mice injected with both FGFR1 shRNA cells showed a decrease in tumour burden in the thoracic cavity as assessed by bioluminescence imaging, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figures 6d and e). However, post-mortem and histological analyses revealed a marked decrease in both the number and the area of metastatic nodules in the lung parenchyma in mice injected with both FGFR1 knockdown clones (Figure 6e and f). No metastases were found in other organs upon macroscopic necropsy of all animals (data not shown), and no apparent differences were observed in tumour volume and osteolysis at the primary tibial injection sites over the 2-week experimental period (Figures 6d and e, and data not shown). These results suggest that silenced FGFR1 signalling in the context of c-Fos overexpression decreases pro-metastatic activity in an orthotopic model of osteosarcoma.

Figure 6.

Effects of FGFR1 silencing on lung metastasis. (a) qPCR analysis showing reduced Fgfr1 mRNA expression in two independent P1.15 murine osteosarcoma cell clones (sh1, sh2) following lentivirally-transduced shRNA constructs, compared to scramble control (Co). Expression is relative to hprt. (b) Western blot analysis of FGFR1 protein levels in sh1 and sh2 P1.15 knockdown subclones showing reduced FGFR1 protein expression. β-actin was used as loading control. (c) In vitro cell growth kinetics of Fgfr1-silenced cells. (d) Representative bioluminescence images of Rag2-/-:IL2Rγ-/- immunocompromised mice (n=7/group) 14d after intratibial injection of either Control (Co) P1.15 transfectants or sh1 and sh2 Fgfr1 knockdown cells. The dotted rectangle identifies the bioluminescence imaging area of the thoracic cavity/lungs. (e) Quantification of bioluminescence in the hindlimbs and lungs. (f) Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained histological sections of lungs, showing metastatic nodules formed in mice 14d after intratibial injection with Co, sh1 and sh2 Fgfr1 knockdown cells. (g) Quantification of the number of metastatic nodules, and the percent metastatic area per lung formed in the lungs of animals injected with Co, sh1 and sh2 cells. All data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs respective controls.

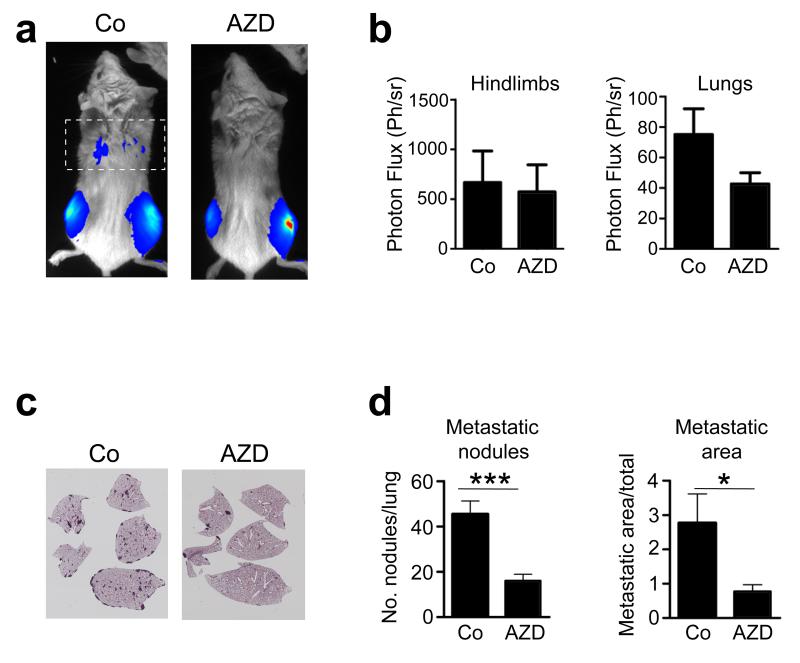

Pharmacological inhibition of FGFR signalling osteosarcoma metastasis in vivo

To demonstrate further the relevance of genetic knockdown of FGFR signalling, we inhibited this pathway in vivo using the pharmacological FGFR1 inhibitor, AZD4547. Using the spontaneous lung osteosarcoma metastasis model, we performed orthotopic injection of wild-type osteosarcoma cells into immunocompromised mice, followed by systemic treatment with either AZD4547 or vehicle. Fourteen days post-injection, a marked decrease in tumour burden was observed in the thoracic cavity as assessed by bioluminescence imaging, whereas no differences were observed in hind limbs (Figures 7a and b). Histological examination revealed a marked decrease in both the number of metastatic lung nodules and the area of metastatic lesions in the lung parenchyma in mice treated with AZD4547 compared to controls (Figures 7c and d). Interestingly, the degree of lung metastasis inhibition by systemic treatment of the FGFR inhibitor was similar to the genetic knockdown of FGFR1 (Figures 6e and f). As before, no metastases were found in other organs upon macroscopic necropsy of all animals (data not shown), and no apparent differences were observed in tumour volume and osteolysis at the primary tibial injection sites over the 2-week experimental period (Figures 7a and b). These data indicate that FGFR signalling is involved in the prometastatic activity of osteosarcoma cells to the lungs.

Figure 7.

Effects of in vivo pharmacological inhibition of FGFR signalling on lung metastasis. (a) Representative bioluminescence images of Rag2-/-:IL2Rγ-/- immunocompromised mice (n=7/group) 14d after intratibial injection of wild-type P1.15 osteosarcoma cells followed by daily administration of either vehicle (Co) or the FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 (AZD). The dotted rectangle identifies the bioluminescence imaging area of the thoracic cavity/lungs. (b) Quantification of bioluminescence in the hindlimbs and lungs. (c) Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained histological sections of lungs, showing metastatic nodules formed in mice 14d after intratibial injection of wild-type P1.15 osteosarcoma cells followed by daily administration of either vehicle (Co) or the FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 (AZD). (d) Quantification of the number of metastatic nodules, and the percent metastatic area per lung formed in the lungs of animals injected with P1.15 cells and treated with AZD4547 as above. All data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs respective controls.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have identified FGFR1 as a novel c-Fos/AP-1-regulated gene and have characterised the function of FGFR1 signalling in driving osteoblast transformation in human and murine osteosarcomas, and demonstrate a novel role for FGFR1 in pulmonary metastasis of osteosarcoma cells.

The role of altered signalling by different FGFRs in sarcomas is poorly understood compared to carcinomas20,27. Our findings of high FGFR1 protein levels in transgenic osteosarcomas from the earliest stages of tumour formation in vivo support its relevant role in its pathogenesis. High FGFR1 expression was paralleled by high pFRS2α expression, which is essential for downstream FGFR1 signalling. The apparent nuclear localisation of FGFR1 and pFRS2α is interesting in view of the continuously increasing importance of nuclear RTK signaling, FGFR1 and FGF ligands, in cancer cell proliferation and migration as well as in osteoblasts20,28-30. The consequences of activated FGFR/FRS2α signalling are mediated, at least in part, by MAPKs as increased FGFR1 expression both in c-Fos-inducible osteoblasts and chondrocytes, as well as in murine and human osteosarcoma cell lines, led to enhanced and sustained FGF2-stimulated MAPK signalling and anchorage-independent growth that were blocked by RTK and MEK inhibitors. The relevance of activated FGFR/FRS2α signaling is further supported by the recent analysis of TCGA datasets where FRS2 was identified as an oncogenic target potentially druggable31.

FGFs are well-known regulators of cell cycle progression and osteoblast proliferation32 and our results, as well as supporting the notion that enhanced FGF/FGFR signalling is a bona fide candidate for driving hyperproliferation of osteoblasts in a pathological setting, identify a specific role for FGFR1 signalling in anchorage-independent growth and metastasis that go beyond its role merely as a mitogen. The additional high expression of both FGF2 and FGF18 that we observed in c-Fos-induced osteosarcomas, in both stromal cells and osteoblasts, is noteworthy since both these ligands are unique in their ability to expand both osteoblast and chondrocyte precursor populations24,33. The high levels of both FGFR1 and FGF ligands suggest that osteoblast hyperproliferation, transformation and tumour progression might be driven in part by an FGF/FGFR autocrine loop20,34-37. Finally, as in vivo models have demonstrated that dosage levels of FGF ligands or FGFRs can differentially mediate their biological effects38,39, our suggestion of a positive autocrine loop, together with other cooperating pathways40, might surpass a threshold required for transformation and explain the potent tumorigenic and metastatic effects.

Interestingly, perturbation of FGFR signaling by mutations in FGFRs-2-4 have been found in a variety of human tumours, however, oncogenic mutations in FGFR1 are extremely rare and it appears that FGFR1-associated malignancies are rather driven through overexpression and/or gene amplification20,41. Our findings are consistent with this notion and also support the recent studies describing FGFR1 amplification in <20% of osteosarcoma patients that correlates with poor response to chemotherapy, as well in a small number of osteosarcoma cell lines that revealed sensitivity to an FGFR inhibitor42,43.

This relevance of FGFR1 signalling in vivo is further underscored by both genetic and pharmacological approaches demonstrating a marked decrease in lung metastases. Of note, the small molecule inhibitor, AZD4547, exhibits inhibitory activity on all FGFRs but has a 10-fold higher affinity to FGFR1. While there is an established role of FGFR signalling in cancer cell migration, invasion and metastatic progression41,44, the mechanisms underlying the role of FGFR in lung metastasis of osteosarcoma cells are not entirely clear. As these cells are derived from c-Fos overexpressing transgenic osteosarcomas, the high metastatic activity observed in this model may be explained in part by increased c-Fos/AP-1 activity which is associated with high expression of prometastatic genes45. In this regard, we have also previously identified potential candidates involved in murine and human osteosarcoma metastasis such as S100A4, periostin and podoplanin, some of which are also c-Fos/AP-1-dependent targets9,11,46,47. Further functional studies would be required to fully elucidate the mechanisms of FGFR1 signalling in osteosarcoma metastasis, either alone or in the context of cross-talk with other c-Fos/AP-1 target genes. It remains, nevertheless, that our findings have potential clinical relevance since lung metastasis represents the most common complication in osteosarcoma patients.

Although the c-Fos transgenic osteosarcoma model was instrumental in identifying the relevance of FGFR1 signalling to osteosarcomas, the analysis of a large number (89) of human osteosarcomas demonstrated not only a significant proportion of high FGFR1-expressing tumours, but also showed a good correlation between high expression of both FGFR1 and c-Fos. Thus, given the well-established heterogeneity in human osteosarcomas, our findings will most likely be representative of a substantial fraction of tumours. Intriguingly, as FGFR1 signalling also appears to be activated by c-Fos in transgenic chondrosarcomas, it is tempting to speculate that our findings could potentially be extrapolated to the subset of human high-grade chondrosarcomas that also express c-Fos and are characterised by their aggressive behavior with similar metastatic lung tropism and poor clinical outcome48.

In summary, our study sheds light on the FGF/FGFR1 pathway in deregulating osteoblast growth during transformation, tumour formation and metastasis. In view of the recent rapid development of FGFR inhibitors as anti-cancer agents, our work supports the expanding repertoire of tumour types that might be targetable by FGFR inhibitors, including AZD4547, that are being used in studies for FGFR1-amplified tumours20,35,49. More importantly, our novel findings of a prometastatic role for FGFR1 have important potential therapeutic applications for the use of FGFR inhibitors in osteosarcoma metastasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and reagents

All general laboratory reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Poole, UK) unless otherwise stated. All cells were cultured in α–MEM containing 10% batch-tested FCS (Lonza, Slough, UK), antibiotics (penicillin 50U/ml, streptomycin 50μg/ml) and L-glutamine (5mM). The tetracycline-inducible osteoblastic AT9.2 and chondroblastic DT12.4 cell lines were cultured as previously described19,26 in the presence of 10 μg/ml (AT9.2) or 1μg/ml (DT12.4) tetracycline to inhibit transgene expression, and c-Fos was induced following withdrawal of tetracycline for 48h. DT8.6 cells represent a subclone of ATDC5 chondrocytes constitutively overexpressing c-Fos26 and P1.15, P1.7, 131 P cells are clonal osteosarcoma cell lines derived from c-Fos murine transgenic osteosarcomas12. Primary mouse osteoblasts were obtained from newborn mouse calvariae as described19 and MG63 human osteosarcoma cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cell lines were mycoplasma-negative. Recombinant FGF2 was purchased from R&D Systems (Abingdon, UK). Transfections were performed using Effectene (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) and clones were selected in gentamycin (G418). Lentiviral shRNA vectors for FGFR1 were obtained from MISSION™ shRNA (Sigma). The FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 was purchased from ChemieTek (Indianapolis, IN).

RNA and protein analyses, growth assays

Northern blotting and semi-quantitative PCR were performed using specific 32P-labelled probes and primers against c-fos, Fgfr1, Gapdh and hprt as described26,50. RNA in situ hybridisation was performed on 5 μm paraffin sections using Fgf2 and Fgf18 riboprobes (a generous gift of Dr. Albert Basson, Dept Craniofacial Development and Stem Cell Biology, KCL) as described previously51. Western blotting was performed on whole cell extracts as described by Sunters et al.19 using specific primary antibodies as follows: c-Fos (sc-52), FGFR1 (sc-121) and β-actin (sc-1616) (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-specific/total MAPK (9926S) and FGFR1 (9740) Cell Signaling Technology), and pFRS2α (ab78195) (Abcam). All antibody concentrations were optimised independently. For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed in 4% PFA/PBS, permeabilised in 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked in 5% BSA and incubated the FGFR1 (sc-121) primary antibody followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5 μm paraffin sections of c-Fos transgenic osteosarcomas or on Tissue Microarrays (TMA) as described previously18 using primary antibodies c-Fos, FGFR1 (sc-121), pFRS2α and BrdU (CalTag) as described above, and a biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (DAKO) followed by visualisation using the ABC system (Vector Laboratories) with DAB substrate (Sigma). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed according to Bozec et al.52 using an antibody against c-Fos (Santa Cruz). Bound and unbound fragments were quantified by real-time PCR.

Anchorage-independent growth assays were performed by seeding cells in triplicates at 2000 cells/well in 12-well plates (Falcon, VWR, Lutterworth, UK) in 0.25% agar overlayed on a 0.6% agar lower layer. Colonies were stained after 3-4 weeks and quantified. For adherent growth curve assays, osteosarcoma cells were plated at 1×104 cells/cm2 and treated 24h later with FGF2 or SU5402. Cells were harvested after 72h at sub-confluence and counted using a haemocytometer.

Animal studies

c-Fos transgenic mice12 were maintained on a C57Bl6/J background at the KCL Biological Services Unit under UK Home Office guidelines (PPL70/7866). Radiographs were taken using a digital radiography system (Faxitron MX-20, Qados UK). For BrdU experiments mice, male 12-week old tumour-bearing mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (stock 5mg/ml) at 100μg/g body weight for 2h prior to sacrifice. Xenografts of intratibial injections were performed on four week-old female Rag2-/-:IL2Rγ-/- immunocompromised mice (Harlan, Barcelona, Spain) as previously described53 under licence CEEA/021-13 (CIMA, Pamplona). Studies were performed at n=7 per group, allocated randomly into experimental groups, and there were no exclusion criteria. All data were analysed unblinded and verified by two independent researchers. AZD4547 was reconstituted in 1% Tween80 and animals received either AZD4547 (12.5mg/kg) or vehicle control daily by oral gavage. Histological analyses were performed following fixation in 4% PFA/PBS followed by EDTA decalcification. 5μm paraffin sections were prepared for either Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining or RNA in situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry staining as described above.

Tissue Microarray Analysis

Tissue microarrays containing a total of 86 cases of human conventional osteosarcoma were constructed as previously described11 following ethical approval of the University of Tokyo (No.1220) following informed consent, and combined with commercially available samples (OS801, US Biomax, Inc., Rockville, MD). Immunohistochemical staining was carried out using anti-FGFR1 and anti-c-Fos polyclonal antibodies as described above. Only immunoreactive tumour cells were included in the quantification, and grading of the immunostaining was scored by estimating the intensity of staining: low expression representing those scored as no or low immunoreactivity, and high expression representing those scored as moderate or high immunoreactivity.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of proliferation rates, tumour growth, and differences in metastatic area were analysed either by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Post hoc test or by Brown-Forsythe and Tamhane’s T2 test. Data are presented as mean ± SD from a minimum of three independent experiments. All in vitro studies were assumed a normal distribution. For non-parametric statistics, data were analysed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney multiple comparison test with Bonferroni’s adjustment. Tissue Microarray Array data were analysed using Fisher’s exact test. Student’s t-test was used where indicated.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay of the murine Fgfr1 promoter showing canonical AP-1 binding sites at −670bp and −997bp from the transcriptional start site. Cell lysates of AT9.2 osteoblasts cultured in the presence of tetracycline (−Fos) or absence of tetracycline (+Fos) for 48 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a c-Fos-specific or control IgG antibody. Bars represent endpoint qPCR-amplified fragments relative to input chromatin.

Supplementary Figure 2. Western blot analysis of total cell lysates from (a) AT9.2 osteoblasts and (b) DT12.4 chondrocytes following 48h c-Fos induction and incubation with FGF2 (10ng/ml) for the indicated times. Samples were probed with the phospho-specific MAPK antibodies as indicated, and total p38, ERK and β-actin were used as loading controls.

Supplementary Figure 3. c-Fos and FGF2 cooperate in morphological transformation. (a) DT12.4 cells cultured in the presence of tetracycline (−Fos) or absence of tetracycline (+Fos) showed increased morphological transformation following c-Fos induction in the presence of FGF2 (10ng/ml). (b) Morphological changes were reversed by pre-treatment with the FGFR inhibitor 20μM SU5402. Bars, 100μm. Insets show representative high magnification images of cell morphology. (c) Long-term culture of cells treated with FGF2 (10ng/ml) form a great number of adherent foci following c-Fos induction (eg. arrow).

Supplementary Figure 4. Radiograph (a,b) and microCT (c) images of c-Fos murine transgenic osteosarcomas. Representative typical radiographs of different stages of tumour formation in this model are indicated as follows: Early stage tumour (stage I, arrow in (a)), intermediate stage tumour (stage II, arrowhead in A), late stage tumour (stage III, arrow in (b) and (c)). Bars, 300μm. (d) Representative immunohistochemistry micrograph of BrdU-labelled osteoblasts (ob) lining bone in transgenic osteosarcoma following in vivo BrdU injection. Bar, 50μm. (e) Quantification of BrdU-positive bone cells in c-Fos transgenic mice before tumour formation (Pre) and at different stages of tumour growth (I, II, III) as shown in (a,b). (f) FGFR1 and (g) c-Fos protein expression in chondrosarcomas that form in c-Fos ES cell chimaeras16. Bars, 50μm.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of Dr Takeshi G Kashima, friend and colleague, without whom this work would not progress. The authors thank Drs. M Albert Basson (KCL, London, UK), Özge Uluçkan (CNIO, Madrid, Spain), and Latifa Bakiri (CNIO, Madrid, Spain) for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript, and Prof Larry J Suva (UAMS, Little Rock, AR) for the microCT analysis. This work was supported in part by: Bone Cancer Research Trust, UK (BCRT04/07; BCRT09/08), Wellcome Trust (059344), Arthritis Research UK (G0538) and Medical Research Council (G78/4785) to AEG; “UTE project FIMA” agreement The Cancer Research Thematic Network of the Health Institute Carlos III (RTICC RD06/0020/0066), Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation & European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “Una manera de hacer Europa” and AECC grant to FL. FL is an investigator from the I3 Program.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando K, Mori K, Verrecchia F, Marc B, Redini F, Heymann D. Molecular alterations associated with osteosarcoma development. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:523432. doi: 10.1155/2012/523432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kansara M, Teng MW, Smyth MJ, Thomas DM. Translational biology of osteosarcoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(11):722–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng AJ, Mutsaers AJ, Baker EK, Walkley CR. Genetically engineered mouse models and human osteosarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2(1):19. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferracini R, Di Renzo MF, Scotlandi K, Baldini N, Olivero M, Lollini P, et al. The Met/HGF receptor is over-expressed in human osteosarcomas and is activated by either a paracrine or an autocrine circuit. Oncogene. 1995;10(4):739–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladanyi M, Park CK, Lewis R, Jhanwar SC, Healey JH, Huvos AG. Sporadic amplification of the MYC gene in human osteosarcomas. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1993;2(3):163–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu T, Ishikawa T, Sugihara E, Kuninaka S, Miyamoto T, Mabuchi Y, et al. c-MYC overexpression with loss of Ink4a/Arf transforms bone marrow stromal cells into osteosarcoma accompanied by loss of adipogenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29(42):5687–99. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franchi A, Calzolari A, Zampi G. Immunohistochemical detection of c-fos and c-jun expression in osseous and cartilaginous tumours of the skeleton. Virchows Arch. 1998;432(6):515–9. doi: 10.1007/s004280050199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu JX, Carpenter PM, Gresens C, Keh R, Niman H, Morris JW, et al. The protooncogene c-fos is over-expressed in the majority of human osteosarcomas. Oncogene. 1990;5(7):989–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujiwara M, Kashima TG, Kunita A, Kii I, Komura D, Grigoriadis AE, et al. Stable knockdown of S100A4 suppresses cell migration and metastasis of osteosarcoma. Tumour Biol. 2011;32(3):611–22. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0160-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanna C, Wan X, Bose S, Cassaday R, Olomu O, Mendoza A, et al. The membrane-cytoskeleton linker ezrin is necessary for osteosarcoma metastasis. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):182–6. doi: 10.1038/nm982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunita A, Kashima TG, Ohazama A, Grigoriadis AE, Fukayama M. Podoplanin is regulated by AP-1 and promotes platelet aggregation and cell migration in osteosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(2):1041–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigoriadis AE, Schellander K, Wang ZQ, Wagner EF. Osteoblasts are target cells for transformation in c-fos transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 1993;122(3):685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenz R, Eferl R, Scheinecker C, Redlich K, Smolen J, Schonthaler HB, et al. Activator protein 1 (Fos/Jun) functions in inflammatory bone and skin disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(1):201. doi: 10.1186/ar2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang ZQ, Liang J, Schellander K, Wagner EF, Grigoriadis AE. c-fos-induced osteosarcoma formation in transgenic mice: cooperativity with c-jun and the role of endogenous c-fos. Cancer Res. 1995;55(24):6244–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.David JP, Mehic D, Bakiri L, Schilling AF, Mandic V, Priemel M, et al. Essential role of RSK2 in c-Fos-dependent osteosarcoma development. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(3):664–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI22877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang ZQ, Grigoriadis AE, Mohle-Steinlein U, Wagner EF. A novel target cell for cfos-induced oncogenesis: development of chondrogenic tumours in embryonic stem cell chimeras. EMBO J. 1991;10(9):2437–50. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jochum W, Passegue E, Wagner EF. AP-1 in mouse development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20(19):2401–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunters A, McCluskey J, Grigoriadis AE. Control of cell cycle gene expression in bone development and during c-Fos-induced osteosarcoma formation. Dev Genet. 1998;22(4):386–97. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:4<386::AID-DVG8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunters A, Thomas DP, Yeudall WA, Grigoriadis AE. Accelerated cell cycle progression in osteoblasts overexpressing the c-fos proto-oncogene: induction of cyclin A and enhanced CDK2 activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(11):9882–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter EP, Fearon AE, Grose RP. Careless talk costs lives: fibroblast growth factor receptor signalling and the consequences of pathway malfunction. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(4):221–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eswarakumar VP, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Cellular signaling by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miraoui H, Marie PJ. Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling crosstalk in skeletogenesis. Sci Signal. 2010;3(146):re9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3146re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ornitz DM. FGF signaling in the developing endochondral skeleton. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marie PJ, Coffin JD, Hurley MM. FGF and FGFR signaling in chondrodysplasias and craniosynostosis. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96(5):888–96. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkie AO. Bad bones, absent smell, selfish testes: the pleiotropic consequences of human FGF receptor mutations. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):187–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas DP, Sunters A, Gentry A, Grigoriadis AE. Inhibition of chondrocyte differentiation in vitro by constitutive and inducible overexpression of the c-fos protooncogene. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 3):439–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(2):116–29. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills IG. Nuclear translocation and functions of growth factor receptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(2):165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabbieti MG, Marchetti L, Gabrielli MG, Menghi M, Materazzi S, Menghi G, et al. Prostaglandins differently regulate FGF-2 and FGF receptor expression and induce nuclear translocation in osteoblasts via MAPK kinase. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;319(2):267–78. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0981-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorensen V, Nilsen T, Wiedlocha A. Functional diversity of FGF-2 isoforms by intracellular sorting. Bioessays. 2006;28(5):504–14. doi: 10.1002/bies.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, McGee J, Chen X, Doman TN, Gong X, Zhang Y, et al. Identification of druggable cancer driver genes amplified across TCGA datasets. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e98293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raucci A, Bellosta P, Grassi R, Basilico C, Mansukhani A. Osteoblast proliferation or differentiation is regulated by relative strengths of opposing signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(2):442–51. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohbayashi N, Shibayama M, Kurotaki Y, Imanishi M, Fujimori T, Itoh N, et al. FGF18 is required for normal cell proliferation and differentiation during osteogenesis and chondrogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16(7):870–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.965702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodo M, Lilli C, Bellucci C, Carinci P, Calvitti M, Pezzetti F, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor autocrine loop controls human osteosarcoma phenotyping and differentiation. Mol Med. 2002;8(7):393–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks AN, Kilgour E, Smith PD. Molecular pathways: fibroblast growth factor signaling: a new therapeutic opportunity in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(7):1855–62. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall ME, Hinz TK, Kono SA, Singleton KR, Bichon B, Ware KE, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors are components of autocrine signaling networks in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(15):5016–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu T, Ishikawa T, Iwai S, Ueki A, Sugihara E, Onishi N, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 is an important factor that maintains cellular immaturity and contributes to aggressiveness of osteosarcoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10(3):454–68. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Behr B, Panetta NJ, Longaker MT, Quarto N. Different endogenous threshold levels of Fibroblast Growth Factor-ligands determine the healing potential of frontal and parietal bones. Bone. 2010;47(2):281–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hajihosseini MK, Lalioti MD, Arthaud S, Burgar HR, Brown JM, Twigg SR, et al. Skeletal development is regulated by fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signalling dynamics. Development. 2004;131(2):325–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.00940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dailey L, Ambrosetti D, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(2):233–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greulich H, Pollock PM. Targeting mutant fibroblast growth factor receptors in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17(5):283–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernanda Amary M, Ye H, Berisha F, Khatri B, Forbes G, Lehovsky K, et al. Fibroblastic growth factor receptor 1 amplification in osteosarcoma is associated with poor response to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer Med. 2014;3(4):980–7. doi: 10.1002/cam4.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guagnano V, Kauffmann A, Wohrle S, Stamm C, Ito M, Barys L, et al. FGFR genetic alterations predict for sensitivity to NVP-BGJ398, a selective pan-FGFR inhibitor. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(12):1118–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grose R, Fantl V, Werner S, Chioni AM, Jarosz M, Rudling R, et al. The role of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b in skin homeostasis and cancer development. EMBO J. 2007;26(5):1268–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozanne BW, Spence HJ, McGarry LC, Hennigan RF. Transcription factors control invasion: AP-1 the first among equals. Oncogene. 2007;26(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durchdewald M, Guinea-Viniegra J, Haag D, Riehl A, Lichter P, Hahn M, et al. Podoplanin is a novel fos target gene in skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68(17):6877–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kashima TG, Nishiyama T, Shimazu K, Shimazaki M, Kii I, Grigoriadis AE, et al. Periostin, a novel marker of intramembranous ossification, is expressed in fibrous dysplasia and in c-Fos-overexpressing bone lesions. Hum Pathol. 2009;40(2):226–37. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamil N, Howie S, Salter DM. Therapeutic molecular targets in human chondrosarcoma. Int J Exp Pathol. 2010;91(5):387–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gavine PR, Mooney L, Kilgour E, Thomas AP, Al-Kadhimi K, Beck S, et al. AZD4547: an orally bioavailable, potent, and selective inhibitor of the fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase family. Cancer Res. 2012;72(8):2045–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kashima T, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi J, Takanashi M, Ishida T, Aburatani H, et al. Overexpression of cadherins suppresses pulmonary metastasis of osteosarcoma in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(2):147–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yaguchi Y, Yu T, Ahmed MU, Berry M, Mason I, Basson MA. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) gene expression in the developing cerebellum suggests multiple roles for FGF signaling during cerebellar morphogenesis and development. Dev Dyn. 2009;238(8):2058–72. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bozec A, Bakiri L, Jimenez M, Schinke T, Amling M, Wagner EF. Fra-2/AP-1 controls bone formation by regulating osteoblast differentiation and collagen production. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(6):1093–106. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vicent S, Luis-Ravelo D, Anton I, Garcia-Tunon I, Borras-Cuesta F, Dotor J, et al. A novel lung cancer signature mediates metastatic bone colonization by a dual mechanism. Cancer Res. 2008;68(7):2275–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay of the murine Fgfr1 promoter showing canonical AP-1 binding sites at −670bp and −997bp from the transcriptional start site. Cell lysates of AT9.2 osteoblasts cultured in the presence of tetracycline (−Fos) or absence of tetracycline (+Fos) for 48 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) with a c-Fos-specific or control IgG antibody. Bars represent endpoint qPCR-amplified fragments relative to input chromatin.

Supplementary Figure 2. Western blot analysis of total cell lysates from (a) AT9.2 osteoblasts and (b) DT12.4 chondrocytes following 48h c-Fos induction and incubation with FGF2 (10ng/ml) for the indicated times. Samples were probed with the phospho-specific MAPK antibodies as indicated, and total p38, ERK and β-actin were used as loading controls.

Supplementary Figure 3. c-Fos and FGF2 cooperate in morphological transformation. (a) DT12.4 cells cultured in the presence of tetracycline (−Fos) or absence of tetracycline (+Fos) showed increased morphological transformation following c-Fos induction in the presence of FGF2 (10ng/ml). (b) Morphological changes were reversed by pre-treatment with the FGFR inhibitor 20μM SU5402. Bars, 100μm. Insets show representative high magnification images of cell morphology. (c) Long-term culture of cells treated with FGF2 (10ng/ml) form a great number of adherent foci following c-Fos induction (eg. arrow).

Supplementary Figure 4. Radiograph (a,b) and microCT (c) images of c-Fos murine transgenic osteosarcomas. Representative typical radiographs of different stages of tumour formation in this model are indicated as follows: Early stage tumour (stage I, arrow in (a)), intermediate stage tumour (stage II, arrowhead in A), late stage tumour (stage III, arrow in (b) and (c)). Bars, 300μm. (d) Representative immunohistochemistry micrograph of BrdU-labelled osteoblasts (ob) lining bone in transgenic osteosarcoma following in vivo BrdU injection. Bar, 50μm. (e) Quantification of BrdU-positive bone cells in c-Fos transgenic mice before tumour formation (Pre) and at different stages of tumour growth (I, II, III) as shown in (a,b). (f) FGFR1 and (g) c-Fos protein expression in chondrosarcomas that form in c-Fos ES cell chimaeras16. Bars, 50μm.