Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate postpartum glucose testing rates in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and to determine factors affecting testing non-compliance in the Korean population. This was a retrospective study of 1,686 patients with GDM from 4 tertiary centers in Korea and data were obtained from medical records. Postpartum glucose testing was conducted using a 2-hr 75-g oral glucose tolerance, fasting glucose, or hemoglobin A1C test. Test results were categorized as normal, prediabetic, and diabetic. The postpartum glucose testing rate was 44.9% (757/1,686 patients); and of 757 patients, 44.1% and 18.4% had pre-diabetes and diabetes, respectively. According to the multivariate analysis, patients with a high parity, larger weight gain during pregnancy, and referral from private clinics due to reasons other than GDM treatment were less likely to receive postpartum glucose testing. However, patients who had pharmacotherapy for GDM were more likely to be screened. In this study, 55.1% of patients with GDM failed to complete postpartum glucose testing. Considering the high prevalence of diabetes (18.4%) at postpartum, clinicians should emphasize the importance of postpartum diabetes screening to patients with factors affecting testing noncompliance.

Keywords: Diabetes, Gestational; Postpartum Glucose Screening; Referral

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as carbohydrate intolerance with onset or first recognition of pregnancy (1). The prevalence of GDM varies from 2.4% to 22.3% worldwide depending on the population studied and the type of diagnostic test employed (2,3); and the prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) continues to increase worldwide (1,4,5).

In Korea, 2% to 5% of all pregnant women reportedly develop GDM (6). GDM contributes to maternal and neonatal morbidity, including gestational hypertensive disorders, fetal macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, and cesarean delivery (7,8); it also produces a significant burden on the economy (9). GDM is also associated with an increased risk for developing type 2 DM, which ranges from 2% to 70% depending on the population being studied and the length of follow-up (10).

Lifestyle intervention and medication can be used to prevent or delay the development of diabetes in women who have been identified early as having a high risk for diabetes (11,12). Therefore, the early identification of DM risk at postpartum is imperative and can be determined by postpartum glucose screening. Consequently, both the American Diabetes Association (7) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (13) recommend postpartum glucose tolerance testing in women with GDM. However, rates of postpartum glucose screening are suboptimal, which range from 18% to 57% (14,15,16,17,18,19,20).

Asian ethnicity is a well-recognized risk factor for the development of GDM (21,22) and more likely to complete postpartum glucose screening than Caucasian women (17,23,24). Therefore, the Asian population is a good candidate to determine clinical and physiological factors that predict and/or contribute to postpartum glucose screening compliance. However, studies available in the context of postpartum glucose testing compliance include Asians as a minor population. In light of this, the present study was conducted to investigate postpartum glucose testing rates in patients with GDM and to determine factors affecting testing non-compliance in the Korean population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This was a retrospective study involving patients with GDM, which was conducted in 4 tertiary centers in Korea between January 1, 2008 and August 31, 2011. Patients who received prenatal care and delivered at the 4 tertiary centers were enrolled in this study. Patients with pre-gestational diabetes were excluded.

Information collected

Demographic, medical, and physiological data were gathered from the women enrolled in this study. We evaluated the age, education level, parity, previous diagnosis of GDM, previous delivery of large for gestational age babies, a history of DM in first-degree relatives, height and weight during the course of pregnancy, gestational age at delivery, pharmacotherapy for GDM during pregnancy, complications of pregnancy (i.e., preeclampsia), birth weight, neonatal intensive care, delivery mode, and postpartum glucose screening.

The pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was calculated for each patient as the weight in kilograms divided by height in square meters. Weight gain was defined as weight at the time of admission for delivery minus the pre-pregnancy weight. The causes for referral were also obtained from patient medical records. Patients were classified based on referral cause (i.e., referral for GDM treatment or for reasons other than GDM treatment).

Diagnosis of GDM

All pregnant women were screened for GDM either at 24-28 weeks of gestation or entry to prenatal care when risk factors for diabetes were present using a 1-hr 50-g oral glucose challenge test. Risk factors that contributed to early screening included a history of GDM; having a first-degree relative with diabetes; a history of having a macrosomic, stillborn, or anomalous infant; and a pre-pregnancy BMI >25 kg/m2 (25).

Women with glucose levels ≥ 140 mg/dL underwent a standard 3-hr 100-g oral glucose tolerance test. The diagnosis of GDM was based on the criteria by Carpenter and Coustan and at least 2 out of the following 4 diagnostic criteria had to be fulfilled: fasting plasma glucose ≥95 mg/dL, and 1-, 2-, and 3-hr glucose levels of ≥180 mg/dL, ≥155 mg/dL, and ≥140 mg/dL, respectively (24).

Management of GDM

Out of the 4 tertiary centers, 3 centers (centers 1, 2, and 3) implemented a multidisciplinary team approach with diverse healthcare professionals (i.e., obstetricians, endocrinologist, and dieticians). After the diagnosis of GDM, all patients visited an endocrinologist to monitor and control their blood glucose levels. However, center 4 used traditional methods where blood glucose was monitored and controlled by obstetricians. All centers provided similar care for patients with GDM, including healthy dietary practices, weight management, exercise, monitoring lifetime risk of diabetes, postpartum glucose screening, and periodic reevaluation of glucose tolerance.

Postpartum glucose test

Postpartum glucose testing was conducted using a 2-hr 75-g oral glucose tolerance, fasting glucose, or hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) test. Postpartum glucose test results were categorized as normal, pre-diabetes (i.e., impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance), and diabetes. The diagnostic criteria for pre-diabetes and diabetes were based on the American Diabetes Association guidelines (26). Diabetes was defined as HbA1C level of ≥6.5%, fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL, 2-hr plasma glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL post-75 g glucose challenge, or a random plasma glucose level of ≥200 mg/dL with symptoms (i.e., polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss). Pre-diabetes was defined as HbA1C level 5.7%-6.4%, fasting glucose level of 100-125 mg/dL (indicating impaired fasting glucose), or a 2-hr glucose level of 140-199 mg/dL post-75 g glucose challenge (indicating impaired glucose tolerance).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Student's t-tests were used to assess the statistical significance between normally distributed continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. A model of multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the factors related to postpartum glucose screening non-compliance after adjustment for covariates that had statistical values of P less than 0.15 in the univariate analysis. Results were considered statistically significant when P values were <0.05 (two-sided). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the institutional review board (KUGH14261-001, 4-2013-0543, KUH1040027, 2014-11-050-001). The need to obtain informed consent was waived.

RESULTS

A total of 1,686 patients with GDM were included during the study period. The mean postpartum glucose testing rate was 44.9% (757/1,686 patients). Based on the oral glucose tolerance test results, 172 (31.2%) had prediabetes, and 54 (9.8%) had diabetes. Based on the fasting glucose results, 82 (35.5%) had prediabetes, and 6 (2.6%) had diabetes. In contrast, using HbA1C test, 165 (43.5%) had prediabetes, and 91 had diabetes (24.0%). With the combination of oral glucose tolerance, the fasting glucose and HbA1C test, 334 (44.1%) had prediabetes, and 139 had diabetes (18.4%).

The characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Patients who were non-compliant to postpartum glucose testing had a higher parity and weight gain during pregnancy compared to women who were compliant to postpartum glucose testing. The incidences of preterm birth and preeclampsia were higher in patients who were non-compliant to postpartum glucose testing compared to women who were compliant to postpartum glucose testing. Patients who were non-compliant to postpartum glucose testing were more likely to be referred from private clinics and less likely to have used pharmacotherapy. However, other characteristics that were evaluated in this study were not different between the 2 groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of women according to postpartum glucose test compliance.

| Characteristics | Non-compliant to postpartum test (n = 929) | Compliant to postpartum test (n = 757) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 33.76 ± 4.20 | 33.67 ± 4.13 | 0.65 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 23.83 ± 4.67 | 23.66 ± 4.44 | 0.48 |

| Weight gain (kg) | 10.67 ± 5.65 | 10.08 ± 5.61 | 0.048 |

| Weight gain (%, kg) | 0.04 | ||

| <11.5 | 58.3 | 61.6 | |

| 11.5-16 | 28.1 | 29.0 | |

| > 16 | 13.6 | 9.4 | |

| Parity (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 42.1 | 49.1 | |

| 1 | 37.4 | 38.8 | |

| ≥2 | 20.6 | 12.0 | |

| Parity (No.) | 0.85 ± 0.94 | 0.66 ± 0.80 | < 0.01 |

| Gestational age at delivery (week) | 37.35 ± 2.94 | 37.85 ± 2.45 | < 0.01 |

| Hemoglobin A1C level (g/dL) | 5.80 ± 0.89 | 6.03 ± 4.43 | 0.23 |

| Education > 12 yr (%) | 67.9 | 72.3 | 0.06 |

| Preterm delivery (%) | 24.8 | 18.0 | < 0.01 |

| Delivery mode-cesarean section (%) | 58.4 | 58.1 | 0.89 |

| Neonatal intensive care (%) | 22.2 | 18.4 | 0.05 |

| History of GDM (%) | 10.2 | 11.1 | 0.54 |

| Previous delivery of LGA baby (%) | 5.7 | 5.3 | 0.72 |

| Diabetes in first-degree relatives (%) | 28.4 | 30.2 | 0.42 |

| Preeclampsia (%) | 6.9 | 4.8 | 0.047 |

| Referral (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| Referral | 46.8 | 41.4 | |

| for GDM treatment | 24.8 | 25.9 | |

| for reasons other than GDM treatment | 22.0 | 15.5 | |

| Pharmacotherapy for GDM (%) | 28.6 | 46.8 | < 0.01 |

BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; LGA, large for gestational age.

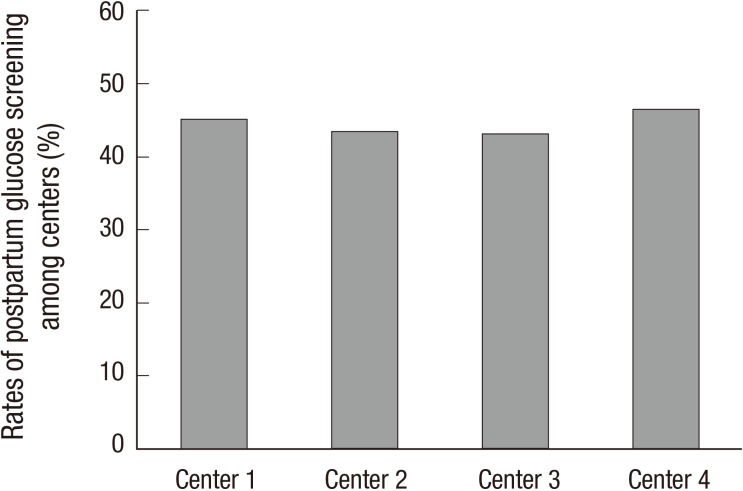

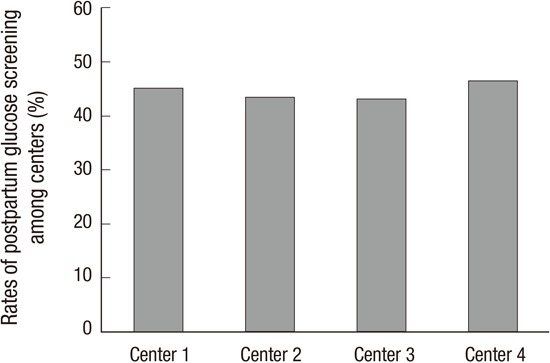

There were no differences in the risk factors that contributed to early screening between women who were and were not compliant to screening (Table 2). Furthermore, there was no difference in the postpartum glucose testing rate among the 4 centers (P=0.716, Fig. 1).

Table 2. Rates of adherence to postpartum glucose test according to risk factors.

| Non-compliant to postpartum test (n=929) | Compliant to postpartum test (n=757) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of risk factors | 0.289 | ||

| 0 | 22.6 | 25.8 | |

| 1 | 43.2 | 40.0 | |

| ≥2 | 34.2 | 34.1 |

Risk factors include pre-pregnancy obesity (body mass index ≥25 kg/m2), old age (age ≥35 yr), history of gestational diabetes mellitus, previous delivery of a large for gestational age baby, and history of diabetes in first-degree relatives.

Fig. 1. The rates of postpartum glucose screening among 4 centers.

We evaluated the factors related to postpartum glucose screening non-compliance by using multivariate logistic regression analysis. According to the multivariate analysis, patients with high parity, larger weight gain during pregnancy, and referral from private clinics due to reasons other than GDM treatment were less likely to receive postpartum glucose testing. However, patients with pharmacotherapy for GDM were more likely to be screened (Table 3).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for non-compliance to postpartum glucose screening.

| Variables | Unadjusted ORs (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted ORs* (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 1.005 (0.982-1.029) | 0.653 | - | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 1.008 (0.986-1.031) | 0.482 | - | |

| Weight gain (kg) | 0.042 | 0.018 | ||

| <11.5 | 1.024 (0.811-1.292) | 0.992 (0.776-1.269) | ||

| 11.5-16 | 1 | 1 | ||

| > 16 | 1.534 (1.096-2.147) | 1.661 (1.157-2.384) | ||

| Parity | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.123 (0.910-1.386) | 1.204 (0.949-1.528) | ||

| ≥2 | 1.997 (1.498-2.661) | 2.202 (1.600-3.031) | ||

| Education > 12 yr (yes) | 0.812 (0.655-1.008) | 0.059 | 0.783 (0.608-1.009) | 0.059 |

| Preterm delivery (yes) | 1.500 (1.182-1.903) | 0.001 | 1.326 (0.959-1.832) | 0.088 |

| Delivery mode: cesarean section (yes) | 1.013 (0.834-1.231) | 0.893 | - | |

| Neonatal intensive care (yes) | 1.266 (0.996-1.611) | 0.054 | 0.939 (0.677-1.301) | 0.704 |

| History of GDM (yes) | 0.908 (0.66-1.241) | 0.544 | - | |

| Previous delivery of LGA baby (yes) | 1.082 (0.709-1.650) | 0.715 | - | |

| Diabetes in first-degree relatives (yes) | 0.916 (0.741-1.133) | 0.419 | - | |

| Preeclampsia (yes) | 1.482 (0.974-2.256) | 0.067 | 1.011 (0.601-1.702) | 0.967 |

| Referral | 0.003 | 0.014 | ||

| No referral | 1 | 1 | ||

| For GDM treatment | 1.054 (0.838-1.327) | 1.261 (0.972-1.639) | ||

| For reasons other than GDM treatment | 1.567 (1.207-2.034) | 1.516 (1.124-2.045) | ||

| Pharmacotherapy for GDM (yes) | 0.456 (0.372-0.558) | < 0.001 | 0.429 (0.340-0.542) | < 0.001 |

*The model is adjusted for covariates that had statistical values of P less than 0.15 in the univariate analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; LGA, large for gestational age.

DISCUSSION

The postpartum glucose testing rate in this study was 44.9% (757/1,686 patients), which is comparable to results from other studies (16). Several studies that were conducted to evaluate independent factors related to postpartum glucose screening compliance in various racial/ethnic cohort groups reported that the Asian group was associated with higher postpartum glucose screening rates (17,23,24). These rates (45%-85%) were higher than the rates from our study population which included only Asian participants. According to these results, the differences in screening rates may be due to the variations in how postpartum glucose screening was recommended by the health care providers to Asian women compared to other racial/ethnic groups and not based on the idea that Asians seek more healthcare given their higher prevalence of diabetes (27).

We identified factors associated with low postpartum glucose screening testing rates. According to the results, patients who were transferred to the center due to reasons other than GDM treatment underwent less frequent postpartum glucose screening tests. Although the precise reason for this association was uncertain, it has been previously reported that women who attended postpartum visits were more likely to complete postpartum glucose screening (16,17,23,24,28). There is a high possibility of discontinuing antenatal and postpartum care in referred patients (i.e., referred and delivered at a tertiary center and then referred back to the private clinic after delivery) indicating that referred patients may not attend postpartum visit. It is possible that these patients may have completed postpartum glucose screening at the private clinics, thereby did not return to the tertiary center for postpartum care. However, Russell et al. (17) reported that women attending postpartum visits at hospital-based clinics were twice as more likely to completing postpartum glucose testing compared to women at community clinics. Moreover, there is a high possibility of omitting postpartum glucose screening at the private clinics due to physician's limited access to the patient's antenatal medical information regarding gestational diabetes or lack of vigilance (8). Therefore, these disturbances in medical care from the prenatal to postpartum periods in referred patients may contribute to the low rates of postpartum glucose screening. GDM is associated with various maternal and fetal complications, such as preeclampsia and large for gestational age babies (7,8). Therefore, patients with GDM should be referred to tertiary centers for appropriate treatment where they should be informed regarding postpartum glucose screening during pregnancy and provided reminders for the screening tests (29).

Compatible to findings from other studies, patients who were non-compliant to postpartum glucose screening had higher parity (14,16,19,24) and were less likely to require insulin for glycemic control (16,19,20,24). Moreover, patients who were non-compliant to postpartum glucose screening had a higher weight gain during pregnancy. This may be a reflection of the "healthy cohort" effect where individuals who are more health-conscious and made efforts to gain less weight during pregnancy are more likely to seek treatment or follow-up (30).

It has been found in a previous study that a multidisciplinary team approach of caring for patients with DM resulted in large improvements in patient management (31). Similarly, Berg et al. (32) reported an improvement in GDM outcome by using a multidisciplinary team approach and Sempowski and Houlden (33) recommended referrals to multidisciplinary teams for intensive glucose control for patients with GDM. It has been reported that visits with an endocrinologist after delivery are associated with better screening rates (28). Although centers 1, 2, and 3 in this study implemented a multidisciplinary team with obstetricians, endocrinologist, and dieticians while center 4 included only obstetricians, we did not observe any differences in postpartum glucose screening rates among these centers. Further studies are needed to evaluate these unexpected results.

Out of 757 women who underwent postpartum glucose screening in this study, 18.4% patients had diabetes, which was higher compared to results from other studies. According to previous reports, the prevalence of diabetes ranged 1%-8% in Caucasians (14,16,17,24). In contrast, our results were comparable to results published by Jang et al. (34) who reported that approximately 15.1% of 311 Korean women had diabetes. These discrepancies between studies may be partially due to the higher prevalence of DM in the Asian population (35,36).

Some limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings. As our study was confined to medical chart review, we could not determine physician dependent factors including frequency of physician contact, use of reminder system and time spent on educating the consequences of GDM, which were associated with non-compliance to postpartum glucose testing. Further studies are needed to examine physician dependent factors for improvement of compliance to postpartum glucose testing.

In conclusion, 55.1% of patients with GDM failed to return to the tertiary center to complete postpartum glucose testing in this study. Considering the high prevalence of DM (18.4%) during the postpartum period in our study population, it seems urgently necessary to educate patients regarding the factors affecting non-compliance and the importance of postpartum glucose testing. Furthermore, patients who are referred from other private clinics should be encouraged for postpartum glucose testing and a collaborative strategy to enhance continuity of care and to alert patients of follow-up testing should be implemented.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Study conception, design and data acquisition: all authors. Data analysis and interpretation: Cho GJ, Kwon JY. Drafting, revision and final approval: all authors.

References

- 1.Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:S141–S146. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Reichelt AJ, Branchtein L, Matos MC, Costa e Forti A, Spichler ER, Pousada JM, Teixeira MM, Yamashita T, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed with a 2-h 75-g oral glucose tolerance test and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1151–1155. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murgia C, Berria R, Minerba L, Malloci B, Daniele C, Zedda P, Ciccotto MG, Sulis S, Murenu M, Tiddia F, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Sardinia: results from an early, universal screening procedure. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1713–1714. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht SS, Kuklina EV, Bansil P, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK, Kourtis AP, Posner SF, Callaghan WM. Diabetes trends among delivery hospitalizations in the U.S., 1994-2004. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:768–773. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrara A, Kahn HS, Quesenberry CP, Riley C, Hedderson MM. An increase in the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: Northern California, 1991-2000. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:526–533. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000113623.18286.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang HC, Cho YM, Park KS, Kim SY, Lee HK, Kim MY, Yang JH, Shin SM. Pregnancy outcome in Korean women with gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed by the Carpenter-Coustan criteria. J Korean Diabetes Assoc. 2004;28:122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:S88–S90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesbitt TS, Gilbert WM, Herrchen B. Shoulder dystocia and associated risk factors with macrosomic infants born in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:476–480. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Quick WW, Yang W, Zhang Y, Baldwin A, Moran J, Moore V, Sahai N, Dall TM. Cost of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States in 2007. Popul Health Manag. 2009;12:165–174. doi: 10.1089/pop.2009.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1862–1868. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saaristo T, Moilanen L, Korpi-Hyövälti E, Saltevo J, Niskanen L, Jokelainen J, Peltonen M, Oksa H, Tuomilehto J, Uusitupa M, et al. Lifestyle intervention for prevention of type 2 diabetes in primary health care: one-year follow-up of the Finnish National Diabetes Prevention Program (FIN-D2D) Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2146–2151. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 435: postpartum screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in women who had gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1419–1421. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ac06b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt KJ, Conway DL. Who returns for postpartum glucose screening following gestational diabetes mellitus? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:404.e1–404.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway DL, Langer O. Effects of new criteria for type 2 diabetes on the rate of postpartum glucose intolerance in women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:610–614. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence JM, Black MH, Hsu JW, Chen W, Sacks DA. Prevalence and timing of postpartum glucose testing and sustained glucose dysregulation after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:569–576. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell MA, Phipps MG, Olson CL, Welch HG, Carpenter MW. Rates of postpartum glucose testing after gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1456–1462. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245446.85868.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almario CV, Ecker T, Moroz LA, Bucovetsky L, Berghella V, Baxter JK. Obstetricians seldom provide postpartum diabetes screening for women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:528.e1–528.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwong S, Mitchell RS, Senior PA, Chik CL. Postpartum diabetes screening: adherence rate and the performance of fasting plasma glucose versus oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2242–2244. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg LR, Moore TR, Murphy H. Gestational diabetes mellitus: antenatal variables as predictors of postpartum glucose intolerance. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00103-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savitz DA, Janevic TM, Engel SM, Kaufman JS, Herring AH. Ethnicity and gestational diabetes in New York City, 1995-2003. BJOG. 2008;115:969–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu SY, Abe K, Hall LR, Kim SY, Njoroge T, Qin C. Gestational diabetes mellitus: all Asians are not alike. Prev Med. 2009;49:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietz PM, Vesco KK, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Bruce FC, Berg CJ, England LJ, Hornbrook MC. Postpartum screening for diabetes after a gestational diabetes mellitus-affected pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:868–874. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184db63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrara A, Peng T, Kim C. Trends in postpartum diabetes screening and subsequent diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus: a report from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:269–274. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 30, September 2001 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 200, December 1994). Gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:525–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitzmiller JL, Dang-Kilduff L, Taslimi MM. Gestational diabetes after delivery. Short-term management and long-term risks. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:S225–S235. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim C, Tabaei BP, Burke R, McEwen LN, Lash RW, Johnson SL, Schwartz KL, Bernstein SJ, Herman WH. Missed opportunities for type 2 diabetes mellitus screening among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1643–1648. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark HD, Graham ID, Karovitch A, Keely EJ. Do postal reminders increase postpartum screening of diabetes mellitus in women with gestational diabetes mellitus? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:634.e1–634.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korpi-Hyövälti E, Laaksonen DE, Schwab U, Heinonen S, Niskanen L. How can we increase postpartum glucose screening in women at high risk for gestational diabetes mellitus? Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:519267. doi: 10.1155/2012/519267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoline C, Kramer A, Roth M. Implementation and methodology of a multidisciplinary disease-state-management program for comprehensive diabetes care. Perm J. 2011;15:43–48. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg M, Adlerberth A, Sultan B, Wennergren M, Wallin G. Early random capillary glucose level screening and multidisciplinary antenatal teamwork to improve outcome in gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:283–290. doi: 10.1080/00016340601110747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sempowski IP, Houlden RL. Managing diabetes during pregnancy. Guide for family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:761–767. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang HC, Yim CH, Han KO, Yoon HK, Han IK, Kim MY, Yang JH, Cho NH. Gestational diabetes mellitus in Korea: prevalence and prediction of glucose intolerance at early postpartum. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ. Type 2 diabetes prevalence in Asian Americans: results of a national health survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:66–69. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon KH, Lee JH, Kim JW, Cho JH, Choi YH, Ko SH, Zimmet P, Son HY. Epidemic obesity and type 2 diabetes in Asia. Lancet. 2006;368:1681–1688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]