Abstract

Research suggests that community involvement is integral to solving public health problems, including involvement in clinical trials—a “gold standard.” Significant racial/ethnic disparities exist in the accrual of participants for clinical trials. Location and cultural aspects of clinical trials influence recruitment and accrual to clinical trials. It is increasingly necessary to be aware of defining characteristics such as location and culture of the populations from which research participants are enrolled. Little research has examined the effect of location and cultural competency in adapting clinical trial research for minority and underserved communities on accrual for clinical trials. Utilizing embedded community academic sites, the authors applied cultural competency frameworks to adapt clinical trial research in order to increase minority participation in nontherapeutic cancer clinical trials. This strategy resulted in successful accrual of participants to new clinical research trials, specifically targeting participation from minority and underserved communities in metropolitan Washington, DC. From 2012 to 2014, a total of 559 participants enrolled across six non-therapeutic clinical trials, representing a 62% increase in the enrollment of blacks in clinical research. Embedding cancer prevention programs and research in the community was shown to be yet another important strategy in the arsenal of approaches that can potentially enhance clinical research enrollment and capacity. The analyses showed that the capacity to acquire cultural knowledge about patients—their physical locales, cultural values, and environments in which they live—is essential to recruiting culturally and ethnically diverse population samples.

Introduction

Considerable attention1–4 has focused on the need to increase underserved racial and ethnic populations in clinical research, especially in light of the cancer health disparities that disproportionately plague these groups. Clinical trials are considered the gold standard of evidence about efficacy of cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment interventions.2,3,5 Clinical trial design and implementation are time-consuming and require a multistep process that is complicated by other factors, including eligibility criteria for clinical trials for underserved racial and ethnic populations, recruitment processes, and patients’ misconceptions or lack of information about clinical trials.6

A growing body of research suggests a correlation between people’s social/structural spaces and their health status.7,8 Location truly matters in cancer prevention and health disparities.7–10 Some limited research has explored geographic proximity and racial disparities in cancer clinical trial participation. Among numerous barriers noted in the literature,4,11,12 two particular factors often cited are lack of transportation to and from the clinical research site and the travel distance to the research site.13–15 Location of the clinical trial site becomes increasingly important to clinical trial success. Place of residence and race were found to be significant predictors of participation in therapeutic and non-therapeutic clinical trials, although patterns differed somewhat between the types of studies.14

The capacity to acquire cultural knowledge about patients and the communities where they live is an essential element of cultural competence indispensable to cancer research and a cancer center’s ability to recruit racially, ethnically diverse populations successfully.16 Researchers must make consistent efforts to include members of diverse populations as equal partners in all aspects of the conduct of research, study design, implementation, and evaluation. A major benefit of this research approach is informed patients and communities prepared to effect and sustain change for improved health and well-being.17

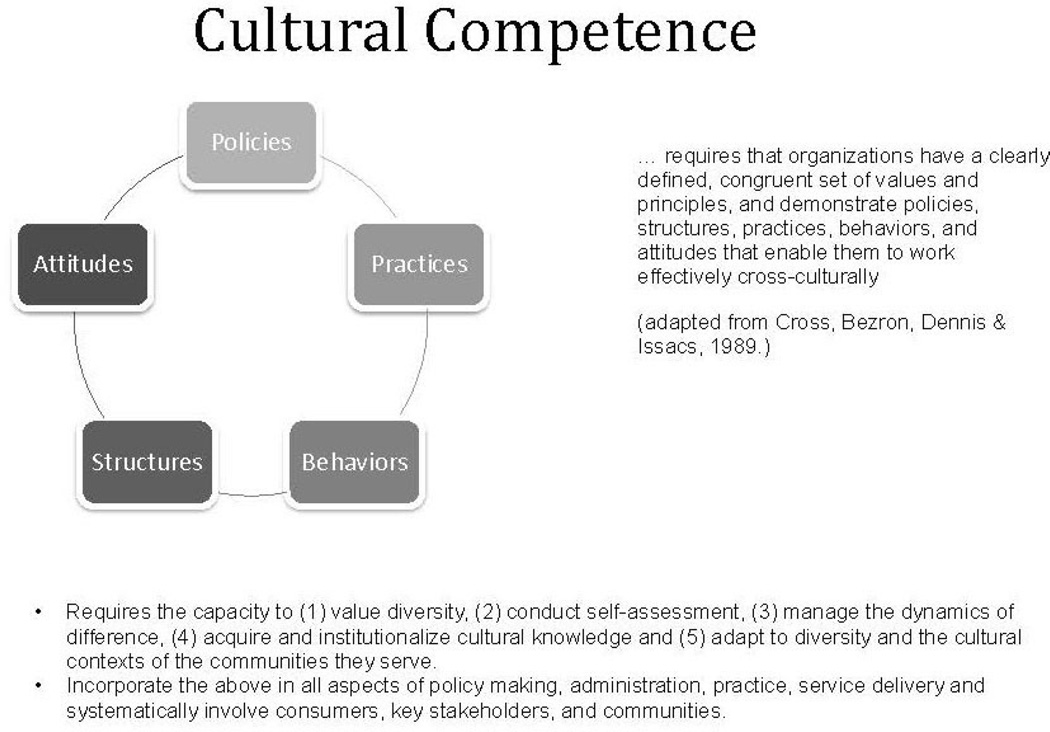

This approach also draws upon the conceptual framework of cultural competence (Figure 1), an evidence-based approach to deliver health care, reduce health and healthcare disparities, and engage diverse communities.18 Cultural competence requires that organizations, including research centers, have a defined set of values and principles and demonstrate policies, structures, practices, behaviors, and attitudes that enable them to work effectively cross-culturally.18,19 At the individual level, cultural competence requires a core set of knowledge and skills, the ability to integrate culture and language in health care and in the conduct of research, the capacity to engage in self-assessment and address biases, and a commitment to continued learning over time. Cultural competence responds to the myriad factors that influence diversity among individuals and groups, such as language, nationality, acculturation, age, gender, sexual orientation, education, literacy, SES, religious or spiritual beliefs, and health beliefs and practices.17 A thorough understanding of these factors and respect for their relevance are necessary to engage diverse individuals, groups, and communities effectively in health disparity interventions. Cultural competence emphasizes reciprocity (i.e., the exchange of information, knowledge, skills, and resources) between academic teams and communities. The authors integrated these philosophical constructs and practices into their community-level, non-therapeutic trials to be responsive to the diversity among individuals who self-identify as African Americans in the Washington, DC metropolitan area.

Figure 1.

Cultural competence conceptual model.

From 2009 to 2011, prior to the establishment of these sites, non-therapeutic clinical trial enrollment had reached an enrollment of 365. Much of the enrollment was due in part to Georgetown–Lombardi enrollment for the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer screening trial. There is a great need to increase clinical trial accrual and ultimately reduce cancer health disparities. Heller and colleagues20 suggested that multiple, flexible strategies designed for providers and participants at provider sites and within communities are needed to enroll under-represented populations into clinical trials. Thus, the study objective was to demonstrate the importance of an academic, community-embedded office in the recruitment and enrollment of racially and ethnically diverse, underserved individuals in clinical trials. This study addressed the roles of access, influence of cultural competent staff, and engaging African American populations in clinical research, specifically non-therapeutic trials.

Methods

Theoretic Framework

This community-embedded approach to increase participation in clinical trials among racially and ethnically diverse, underserved communities draws upon the tenets of community participatory research principles21–24 and the socioecologic model,25 which recognizes the importance of the social and physical structures of communities. This model posits that health and behavior are influenced at multiple levels—intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy.25 These multiple levels of influences are inextricably linked and interact with one another in a social environment where other factors (i.e., biological, behavioral, social–cultural, and physical environment) are at play in one social environment.25–29

These factors can be assessed at all the different levels. In examining the role and impact of colocation— the two Georgetown–Lombardi community sites—the socioecologic model serves as a lens to delineate both the individual and community levels, as well as other multilevel, sociocultural, and structural factors, such as residential geographic proximity, in addressing cancer prevention and health disparities.

Cultural Competency Approach

Ensuring that study methods (i.e., team composition, procedures, recruitment materials) for cancer studies are in concert with values of under-represented populations positively impacts study participation.30 In adapting clinical research for underserved racial and ethnic groups, the authors’ approach involved mixed-method strategies that focused on location, cultural competency, and community-based participatory research methodologies (e.g., focus groups, inclusion of community residents as members of the research team, community needs assessments, town hall meetings, community mapping, and surveys). Other frameworks also emphasized community-based participatory research31 and community competency.32

The Georgetown–Lombardi Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research (OMH) and the Capital Breast Cancer Center (CBCC), our two community-based offices (CBOs) located within a 1-mile radius of each other, were opened in the southeast regions of Washington, DC. The OMH (opened in 2012) is composed of Georgetown–Lombardi faculty and staff who seek to engage the community in clinical research. Costs associated with the opening of these two community sites were cost neutral. One major grant award received, NIH and the National Cancer Institutes’ P60 Center for Excellence in Disparities, covers the costs of the space and operation of the facility. A strong institutional commitment is essential; direct costs from additional grants support a significant number of staff members.

Between the two centers, there is a diverse faculty and staff (African American, white, Chinese, Indian, Hispanic), diverse faculty in rank (full professor, associate professor, two assistant professors, postdoctoral fellow), and diverse faculty and staff in terms of scientific and research expertise (e.g., a breast surgeon, nurse practitioners, an exercise physiologist, a health communication scientist, community health educators, and bilingual patient navigators).

Faculty and staff designed a number of non-therapeutic cancer clinical research trials specifically adapted for under-represented groups living in the southwest and southeast communities of Washington, DC. CBCC provides mammography screening to racially, ethnically diverse and underserved women in the Washington, DC metropolitan area and serves as a recruitment hub for clinical research. CBCC first opened in 2004. Initially established to provide breast health and mammography services primarily to under-represented populations, CBCC has evolved into an active research site for clinical trial recruitment with the establishment of research assistance and guidance from faculty and staff of the OMH. OMH faculty and staff work with the CBCC staff to develop community-level clinical research using both community sites. The CBO site locations were strategically selected based on the following criteria: they had to be geographically situated in medically underserved areas, located in communities with high incidence of cancer rates, and placed in geographic proximity to culturally diverse communities. Moreover, Georgetown–Lombardi is a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center and is required to address the needs of the georgraphic areas from which it may potentially attract patients. Studies are designed to be responsive to this requirement.

Facilitation of Access Into the Community

Initial access to the community was a result of two community advisory boards (CABs). There are two Georgetown–Lombardi CABs: the OMH community advisory board and the CBCC community advisory board. Both serve as an entry point into the community and to build research capacity, programmatic efforts, and further support our goal of integrating and sustaining cultural competency through every aspect of clinical trial research. The establishment and reliance on CABs ensure that communities are respected, informed, and engaged.30 CABs also serve to foster community trust, reciprocity, transparency, and better penetration within communities and to collaborate to create culturally relevant messages.

The OMH CAB comprises members representing various neighborhoods in the District with a particular focus on neighborhoods in the southeast quadrant of the city such as Anacostia, referred to as Ward 8, which is designated as a medically underserved area.33 Board membership includes residents living in the neighborhoods, community-based physicians, and representatives from non-profit and community-based organizations, churches, media, and government organizations. The CBCC CAB serves as an advocate for the health and wellness of low-income minority women in the Washington, DC metropolitan area and seeks to expand the understanding of breast care and health education for the community. Board members are community activists, interested professionals, and valued leaders. Current members include breast cancer survivors, physicians, community-based organization directors, corporate business professionals, and patient advocates.

With the CABs acting, as Everett Rogers described in his seminal book, Diffusions of Innovation, as “change agents”—individuals who influence clients’ innovation decisions in a direction deemed desirable by a change agency34—to gain entry into the community, faculty and staff held several conversations and planning meetings with key stakeholders (e.g., residents, legislators, community advocates, representatives of other CBOs). The CABs and these additional stakeholders acted as change agents, or advocates, for clinical research participation.

Many discussions focused on changing community demographics, health disparities, the need for minority participation in clinical trials, comorbidities and other barriers, mistrust clinical trials, biospecimens, health communication preferences, cancer prevention, physical activity, nutrition, community health needs, and priorities. These topics were similar to other issues reported in the literature as well.5 The discussions led to the need to conduct a community assessment. In partnership with the CABs, and along with other community residents, the study team conducted a healthy lifestyles’ community assessment involving town hall meetings, surveys, focus groups, and geomapping of community assets and needs.

As the assessment progressed, aspects were adjusted in response to the CABs’ and community residents’ guidance and feedback. This investment in employing CABs and other community residents to conduct outreach and education and initial screening in the community contributed to a saturation of information in the community about Georgetown–Lombardi research studies. Moreover, the two Georgetown–Lombardi community CBOs provide greater geographica proximity for participants to the clinical research trials. Both offices are located near Metro (train) and bus locations, within walking distances for many of the study participants.

Cultural Competence

Using the aforementioned cultural competence framework, the authors integrated various culturally competent strategies in the study design of their clinical trial research. First, they put together diverse Georgetown–Lombardi faculty and staff that were involved in clinical research and also were inclusive of community residents and professional healthcare providers. Second, they made sure that their staff members were trained formally or informally on the elements of cultural competence:

valuing diversity among the academic and community teams and diversity within the current and potential pool of research participants;

conducting self-assessments;

managing the dynamics of difference;

acquiring and institutionalizing cultural knowledge; and

adapting to diversity and the cultural contexts of communities served.17,35–38

The faculty and staff cultural competence training consisted of didactic training with Georgetown University Center, Howard University Center for Translational Research, and Georgetown National Center for Cultural Competence, and utilization of online training resources, also from the Georgetown National Center of Cultural Competence. Cultural competence training and skill development among faculty and staff are ongoing. A person who is culturally competent has a core set of knowledge and skills in how to integrate culture and language effectively in the delivery of health care and avails themself of continued learning over time.33 Training in and of itself does not make one culturally competent. It is also the experience and lessons learned within diverse communities—in other words, the intentional acquisition of deeper knowledge and skills.36 The authors’ clinical research was guided by this cultural competence approach, and they developed it with input from the community.

Third, individually and as a team, the authors reviewed all study procedures, community engagement, consent documents and procedures, recruitment materials, and data collection tools (e.g., surveys, focus group and interview guides) for health literacy, cultural and linguistic appropriateness, and accuracy. Faculty and staff engagements with study participants were monitored by study principal investigators and team members for demonstration across the studies of core proficiency in cultural competence. Practices were reviewed or pre-tested with either members of the CABs or residents representing the targeted groups.

Results

Six investigator-initiated clinical trials targeting underserved and low-income African American women were open for enrollment. Table 1 describes participant enrollment in the six clinical research trials. Three trials focused on breast cancer, one on smoking cessation, and two on the human papillomavirus (HPV). The percentage of targeted enrolled participants in the trials ranged from 65% to 100%, reaching a total enrollment of 559 participants across the six represented trials. Participants were all African American, and the age range of the study participants was 13–65 years. Four trials were female-only participants (Metabolic Syndrome and Breast Cancer Risks, Exergaming and Breast Cancer Biomarkers, Quit & Fit, and Improving Exercise and Diet in Breast Cancer Survivors). One HPV trial included adult male and female parents (A Brief HPV and HPV Vaccine Educational Intervention Targeting a Vulnerable Population), and another HPV trial included male adolescents (HPV Awareness and Vaccine Acceptability among Inner-City Black Males). Study designs on trials reported here included three RCTs, one educational intervention (i.e., a face-to face didactic workshop), and one mixed-methods (e.g., focus groups, key informant interviews, and surveys). Two trials failed to meet their target accrual rates. The HPV Awareness and Vaccine Acceptability among Inner-City Black Males is still recruiting to complete the qualitative phase. The Quit & Fit trial targeted enrollment was 40 and actual enrollment was 38.

Table 1.

Enrollment in Clinical Research Studies for African-Americans (2012–2014)

| Title | Description | Target | Accrual N | Enrollment rate % | Study design |

Age | Funding source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Syndrome and Breast Cancer Risk | Exercise intervention among obese, metabolically unhealthy black women at high risk for breast cancer | 160 | 160 | 100% | RCT | 45–65 | P60 / NIMHD |

| Exergaming and Breast Cancer Biomarkers | RCT on the effects of exergaming among overweight/obes e black women | 100 | 100 | 100% | RCT | 40–60 | R21 / NCI |

| Quit and Fit – A Tobacco Cessation and Energy Balance Pilot for African Americans | A 12-week RCT among black women to investigate the effectiveness of an intervention in addition to nicotine lozenges on smoking cessation | 40 | 38 | 95% | RCT | 18–65 | CCSG P30 / NCI |

| Improving Exercise and Diet in Breast Cancer Survivors | Feasibility study to improve breast biomarkers via exercise intervention | 48 | 31 | 65% | RCT | 45–65 | R21 / NCI |

| A Brief HPV and HPV Vaccine Educational Intervention Targeting A Vulnerable Population | This study seeks to develop and test the feasibility of a community-based parent-targeted HPV educational intervention for residents living in a D.C. family shelter who receive health services from Georgetown University Medical Center’s onsite student-run medical clinic | 80 | 80 | 100% | Cross-sectional pre- and post survey | 25–65 | Paul Carey Foundation Schlegel Lab Ovarian and Gynecologic Coalition—Rhonda’s Club |

| HPV Awareness and Vaccine Acceptability among Inner-City Black Males | Using a mixed-method sequential approach, this study seeks to characterize factors that facilitate or impede HPV health communication and vaccine acceptance among black male adolescents | 192 | 150 | 78% | Mixed-methods (survey, focus groups) | 13–17 | R03 / NCI |

Discussion

Results demonstrate that male and female African Americans are interested in participating in clinical research that employs culturally competent methods that are practical and relevant to their interests and needs. The high enrollment rates for the clinical trials demonstrate that the authors were able to recruit underserved African American women successfully. From 2012 to 2014, since engaging in the aforementioned culturally competent, community-based strategies, the enrollment of 559 represents a 62.0% increase in black participants reported for Georgetown–Lombardi NIH and National Cancer Center’s P30 Cancer Support Center Grant (N=345). The Cancer Support Center Grant supports cancer research center infrastructure that enhances collaborative, transdisciplinary research productivity and provides funding for cancer research programs, shared research resources, scientific and administrative management, planning and evaluation activities, development of new scientific opportunities, and centralized clinical trial oversight and functions.39

Instrumental to this success was the development of a strong community capacity–building and clinical research cancer recruitment strategy. Moreover, this approach goes beyond just locating the OMH in an underserved area. Bringing the Georgetown–Lombardi research faculty and staff closer to the community and establishing OMH were the catalysts that helped CBCC evolve into a programmatic research entity and that together improved engagement of the community in clinical research.

The basic premises underlying this community capacity–building and clinical trial cancer research recruitment strategy are:

the importance of physical proximity of cancer prevention programs and trial interventions within a given community; and

cultural competence of the program design, faculty, and staff together with the respect and trust they build and share with clinical trial participants and the community.

Place does matter—where people live, work, go to school, worship, and play are important social determinants of health.7 The authors’ perspective suggests that where cancer prevention programs and clinical trials are geographically located is important in improving various cancer prevention and cancer health disparities’ outcomes. Moreover, this approach assisted the academic and community teams in designing culturally competent, non-therapeutic clinical trials and in matching trials to the specific interests and needs of the community.

Cultural competence assists with the goal of engendering community trust and creating authentic and diverse community partnerships to address cancer prevention and cancer health disparities. Everett Rogers34 posited that in order to effect changes, we must identify the change agents.

The authors believe their approach has helped do this. It enabled them to build important relationships and partnerships; to empower community residents to share in effecting change in their neighborhoods through education, training, and research; and to increase research and sustainability capacity for clinical trial design and implementation.

Though Georgetown–Lombardi’s particular trials focused only on African American populations, other cultural competency strategies may be needed for other racial and ethnic groups. Cultural competency proficiency is not “one size fits all.” Again, it is a process, and, as such, other strategies may be needed for other populations; the literature offers a plethora of methods to start this process for other racial and ethnic groups.40,41

The authors are also unfortunately unable to provide additional data about the types of studies supported by the Center/CBCC during 2009–2011 in order that more statistical analyses can be conducted. Because the OMH was established in 2012, there are no prior data. In addition, the authors report no data on retention, compliance, or specific study outcomes among the recruited individuals. Furthermore, the trials were only non-therapeutic. The strong community capacity and competency that have been fostered in Washington, DC communities coupled with this cultural competency approach sets a benchmark for the design of larger, more robust, community-engaged clinical research. Future efforts and plans are underway to expand similar recruitment and enrollment strategies in the design of both therapeutic and non-therapeutic clinical trials across race, ethnicity, and SES.

Acknowledgments

We owe a depth of gratitude to the community residents of the Washington, DC. This study was supported in part by NIH/National Cancer Institute K01 Grant 5 K01 CA155417-05 Career Award to Sherrie Flynt Wallington, the NIH Comprehensive Centers Support Grant P30CA51008, and NIH/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities P60MD006920 Center of Excellence for Health Disparities in the Nation’s Award to Lucile Adams-Campbell.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Langford R, Panter-Brick C. A health equity critique of social marketing: Where interventions have impact but insufficient reach. Soc Sci Med. 2013;83:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denicoff AM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Grubbs SS, et al. The National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Trial Accrual Symposium: Summary and recommendations. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(6):267–276. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2013.001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCaskill-Stevens W, Wilson JW, Cook ED, et al. National surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project study of tamoxifen and raloxifene trial: Advancing the science of recruitment and breast cancer risk assessment in minority communities. Clin Trials. 2013;10(2):280–291. doi: 10.1177/1740774512470315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1740774512470315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallington SF, Luta G, Noone AM, et al. Assessing the awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials among immigrant Latinos. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):335–343. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9450-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9450-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langford AT, Resnicow K, Dimond EP, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical trial enrollment, refusal rates, ineligibility, and reasons for decline among patients at sites in the national cancer institute's community cancer centers program. Cancer. 2014;120(6):877–884. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmotzer GL. Barriers and facilitators to participation of minorities in clinical trials. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(2):226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IOM. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenger NK. Are we there yet? Closing the gender gap in coronary heart disease recognition, management and outcomes. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;11(11):1447–1450. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2013.845526. http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14779072.2013.845526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunderson CC, Tergas AI, Fleury AC, Diaz-Montes TP, Giuntoli RL., 2nd Primary uterine cancer in Maryland: Impact of distance on access to surgical care at high-volume hospitals. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(7):1244–1251. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31829ea002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31829ea002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onega T, Weiss J, Kerlikowske K, et al. The influence of race/ethnicity and place of service on breast reconstruction for Medicare beneficiaries with mastectomy. Springerplus. 2014;3 doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-416. 416-1801-3-416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-3-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vickers AJ. Clinical trials in crisis: Four simple methodologic fixes. Clin Trials. 2014;11(6):615–621. doi: 10.1177/1740774514553681. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1740774514553681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coakley M, Fadiran EO, Parrish LJ, Griffith RA, Weiss E, Carter C. Dialogues on diversifying clinical trials: Successful strategies for engaging women and minorities in clinical trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(7):713–716. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3733. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanarek NF, Tsai HL, Metzger-Gaud S, et al. Geographic proximity and racial disparities in cancer clinical trial participation. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(12):1343–1351. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itty TL, Hodge FS, Martinez F. Shared and unshared barriers to cancer symptom management among urban and rural American Indians. J Rural Health. 2014;30(2):206–213. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brien RL, Kosoko-Lasaki O, Cook CT, Kissell J, Peak F, Williams EH. Self-assessment of cultural attitudes and competence of clinical investigators to enhance recruitment and participation of minority populations in research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(5):674–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goode TD, Dunne MC, Bronheim SM. The evidence base for cultural and linguistic competency in health care. The Commonwealth Fund; 2006. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cross T, Bazron B, Dennis K, Isaacs M. Towards a culturally competent system of care. Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center; 1989. [October 21, 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conceptual frameworks/models, guiding values and principles. http://nccc.georgetown.edu/foundations/frameworks.html. Updated 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heller C, Balls-Berry JE, Nery JD, et al. Strategies addressing barriers to clinical trial enrollment of underrepresented populations: A systematic review. [Review] Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39(2):169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minkler M. Ethical challenges for the "outside" researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(6):684–697. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269566. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090198104269566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etowa J, Wiens J, Bernard WT, Clow B. Determinants of black women's health in rural and remote communities. Can J Nurs Res. 2007;39(3):56–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toledo RF, Giatti LL. Challenges to participation in action research. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(1):162–173. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychol Rev. 1994;101(4):568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diez-Roux AV. Bringing context back into epidemiology: Variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):216–222. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.216. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.88.2.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.IOM. Health and behavior the interplay of biological, behavioral, and societal influences. 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: A critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–122. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.2.111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.55.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manda-Taylor L. Establishing community advisory boards for clinical trial research in Malawi: Engendering ethical conduct in research. Malawi Med J. 2013;25(4):96–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson RG. Community development model for public health applications: overview of a model to eliminate population disparities. Health. Promot. Pract. 2005;6(3):338–346. doi: 10.1177/1524839905276036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524839905276036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Census Bureau. Medically underserved areas/populations. 2010 http://www.census.gov/.

- 34.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilbert J, Goode TD, Dunne C. [October 24, 2014];Cultural awareness. From the Curricula enhancement module series. Curricula Enhancement Module Series, National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goode T, Harrison S. Policy brief 3: Cultural competence in primary health care. Partnerships for a research agenda. Georgetown University Child Development Center; 2000. [October 24, 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epstein JL. Improving family and community involvement in secondary schools. Principal Leadership. 2007;(8):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goode T, Harris-Haywood S, Bronheim S, Smith K, Murphy L. The role of self-assessment in achieving cultural and linguistic competence and its impact on addressing health care disparities. In: Kinsey PJ, Louden DM, editors. Health, ethnicity, and well-being: An African American perspective. Lincoln University, PA: The Lincoln University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.NIH, National Cancer Institute. [Retrieved April, 29, 2015];Cancer Center Support Grant. 2015 http://cancercenters.cancer.gov/.

- 40.Riley-Jacome M, Parker BA, Waltz EC. Weaving latino cultural concepts into Preparedness Core Competency training. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(Suppl 5):S89–100. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tommbe R, MacLaren DJ, Redman-MacLaren ML, Mafile'o TL, Asugeni L, McBride WJ. Researching male circumcision for HIV prevention in Papua New Guinea: a process that incorporates science, faith and culture. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]