Abstract

Acute liver failure can be the consequence of various etiologies, with most cases arising from drug-induced hepatotoxicity in Western countries. Despite advances in this field, the management of acute liver failure continues to be one of the most challenging problems in clinical medicine. The availability of adequate experimental models is of crucial importance to provide a better understanding of this condition and to allow identification of novel drug targets, testing the efficacy of new therapeutic interventions and acting as models for assessing mechanisms of toxicity. Experimental models of hepatotoxicity related to acute liver failure rely on surgical procedures, chemical exposure or viral infection. Each of these models has a number of strengths and weaknesses. This paper specifically reviews commonly used chemical in vivo and in vitro models of hepatotoxicity associated with acute liver failure.

Keywords: Hepatotoxicity, acute liver failure, acetaminophen, D-galactosamine, Fas ligand, concanavalin A

1. Introduction

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity is the leading cause of acute liver failure in North American and European countries, whereby acetaminophen (APAP)/paracetamol (Figure 1.) accounts for nearly 50% of all cases. In contrast, the incidence of acute liver failure due to hepatitis A and B infection declined in the last decades, reaching 10% of the cases. In addition, nearly 5% of the clinical cases have features of auto-immune hepatitis (Ichai and Samuel 2011; Lee 2008). Generally, liver transplantation remains the most effective treatment of acute liver failure (Polson and Lee 2005), but is not widely available because of a lack of donor organs, expense and expertise (Ostapowicz et al. 2002). It also has the disadvantage of requiring lifelong immunosuppression. Above that, the survival rate of acute liver failure has plateaued in recent years. It is obvious that major new advances in disease understanding are needed to further improve the overall outcome (Ostapowicz and Lee 2000; Riordan and Williams 2008). Therefore, in vivo and in vitro models of drug toxicity and acute liver failure are critical for identifying novel drug targets and for testing new therapeutic interventions.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of acetaminophen/paracetamol.

Despite steady progress, the knowledge of the pathophysiological basis of drug toxicity and acute liver failure is still very rudimentary. The development of appropriate models is of paramount importance for understanding the pathogenesis and progression of acute liver failure as well as the mechanisms involved in liver regeneration. Over the years, many attempts have been made to develop suitable in vivo models for these purposes, relying on surgical procedures, chemical exposure or viral infection, which have been reviewed previously (Bélanger and Butterworth 2005; Filipponi and Mosca 2001; Newsome et al. 2000; Terblanche and Hickman 1991; Tuñón et al. 2009). In this respect, Terblanche and Hickman have introduced a series of requirements for an ideal model of acute liver failure (Terblanche and Hickman 1991). To date, not a single model that accurately reproduces all facets of human acute liver failure has been established. However, given the obvious ethical constraints in carrying out research on patients, animal models have a fundamental role to play in future studies. In addition, in vitro systems are valuable tools to investigate the cellular events related to acute liver failure at a more mechanistic level, which is often not possible in vivo (Godoy et al. 2013). In the present paper, focus is put on widely used chemicals in vivo and in vitro models of hepatotoxicity involved in acute liver failure with distinct mechanisms, ranging from reactive metabolite induced necrosis, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-mediated inflammatory injury, apoptosis and secondary necrosis and immune mediated liver injury (Table 1.). The most widely used experimental model related to acute liver failure is the APAP-based model. This model is often selected due to the epidemiological relevance in humans. Furthermore, the pathophysiology in mice reflects very closely what is observed in humans, including reactive metabolite formation (McGill and Jaeschke 2013), mitochondrial damage with oxidative stress (Adamson and Harman 1993; Cover et al. 2005; Jaeschke 1990; Kon et al. 2007; Kon et al. 2004; Reid et al. 2005; Saito et al. 2010a; Saito et al. 2010b), followed by DNA fragmentation (Bajt et al. 2008; Cover et al. 2005; Shen et al. 1992) and necrosis (Bajt et al. 2008; Gujral et al. 2002; Jaeschke et al. 2012a; Williams et al. 2011). As an APAP overdose mainly causes oncotic necrosis, alternative models are needed to study apoptosis and secondary necrosis in liver injury. This can be achieved using the D-galactosamine/endotoxin (Gal/ET) or Fas ligand (FasL)-based models. The Gal/ET-based model is useful to study TNFα-mediated apoptotic signaling mechanisms (Jaeschke et al. 1998; Leist et al. 1995) and inflammatory-mediated liver injury (Gujral et al. 2004; Jaeschke et al. 1998), while the FasL-based model is suitable to study apoptosis (Ogasawara et al. 1993; Schüngel et al. 2009) and secondary necrosis pathways in liver (Bajt et al. 2000; Ogasawara et al. 1993). In addition, concanavalin A (ConA) has been used frequently as a model of immune-mediated liver injury (Tiegs et al. 1992; Tsutsui and Nishiguchi 2014; Wang et al. 2012), which is considered as a relevant model of auto-immune and viral hepatitis.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of chemical-induced hepatotoxicity (TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α).

| Acetaminophen | Reactive metabolite formation | (Mitchell et al. 1973a and 1973b; Dahlin et al., 1984) |

| Mitochondrial damage | (Cover et al. 2005; Kon et al. 2004 and 2007; Saito et al. 2010a and 2010b) | |

| DNA fragmentation | (Bajt et al. 2008; Cover et al. 2005; Shen et al. 1992) | |

| Oxidant stress | (Adamson and Harman 1993; Jaeschke 1990; Reid et al. 2005) | |

| Necrosis | (Bajt et al. 2008; Gujral et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2011) | |

| Galactosamine/endotoxin | TNFα-mediated apoptosis | (Jaeschke et al. 1998; Leist et al. 1995) |

| Inflammatory liver injury | (Gujral et al. 2004; Jaeschke et al. 1998) | |

| Fas ligand | Apoptosis | (Ogasawara et al. 1993; Schüngel et al. 2009) |

| Secondary necrosis | (Bajt et al. 2000; Ogasawara et al. 1993) | |

| Concanavalin A | Immune-mediated liver injury | (Tiegs et al. 1992; Tsutsui and Nishiguchi 2014; Wang et al. 2012) |

2. Acetaminophen-based model

An acute overdose of APAP in mice best reproduces the pathophysiology of liver injury in humans compared to other relevant species (Davis et al. 1974; McGill et al. 2012a; Xie et al. 2014). A dose of 200 mg/kg for fasted mice or 400 mg/kg for fed mice is sufficient to achieve significant liver toxicity within 6 to 24 hours. In contrast, rats are much less susceptible to APAP and develop only minor liver injury even at high doses of 1 g/kg (McGill et al. 2012b). As such, the rat model thus has very limited relevance for humans. Although mice are generally better models for human APAP toxicity, strain differences need to be considered (Harrill et al. 2009). In addition, female mice are generally less susceptible to APAP-triggered liver insults than male mice due to accelerated recovery of hepatic glutathione (GSH) levels (Du et al. 2014). However, there is no epidemiological evidence for lower susceptibility of female patients to APAP overdose. Furthermore, mice do not fully reproduce the human condition of acute liver failure. In some strains, such as C3Heb/FeJ mice, animals die from hypovolemic shock because of the extensive hemorrhage in the liver after endothelial cell damage (Lawson et al. 2000b; Yin et al. 2010). This is not the case in humans with acute liver failure who mostly die because of sepsis due to compromised innate immune function of the liver and circulating leukocytes (Mookerjee et al. 2007). However, lack of regeneration, a potential cause for developing acute liver failure, can be mimicked in mice (Bhushan et al. 2014).

To effectively use the mouse model, a few issues need to be considered (Figure 2.). First, the mechanism of toxicity depends on the formation of a reactive metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system (Dahlin et al. 1984; Mitchell et al. 1973a; Streeter et al. 1984), especially CYP2E1 (Lee et al. 1996; McClain et al. 1980; Sato and Lieber 1981; Sato et al. 1981). NAPQI is detoxified by GSH (Albano et al. 1985; Corcoran and Wong 1986; Mitchell et al. 1973b; Rosen et al. 1984), but can equally bind to cysteine sulfhydryl groups of proteins (Hoffmann et al. 1985; Jollow et al. 1973; Streeter et al. 1984). These early mechanistic findings led to the discovery of N-acetyl-cysteine as a very effective antidote for APAP-induced liver injury when administered early. The therapeutic effect of N-acetylcysteine is based on the replenishment of the GSH, scavenging reactive oxygen in mitochondria and support of the mitochondrial energy metabolism (Corcoran et al. 1985a and 1985b; Corcoran and Wong 1986; Knight et al. 2002; Saito et al. 2010b). In line with this, binding of NAPQI to mitochondrial proteins appears to be important for the initiation of mitochondrial oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation (Cover et al. 2005; Hinson et al. 1998; Jaeschke 1990; Qiu et al. 2001; Tirmenstein and Nelson 1989). The early oxidant stress triggers activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases that ultimately cause c-jun N-terminal kinase activation (p-JNK), which then translocates to the mitochondria and further exacerbates the mitochondrial oxidant stress (Hanawa et al. 2008; Saito et al. 2010a). The oxidant stress, together with lysosomal iron, promotes the mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, resulting in the collapse of the membrane potential and cessation of adenosine triphosphate synthesis (Kon et al. 2004 and 2007; Masubuchi et al. 2005). Early formation of a Bax-based pore in the outer mitochondrial membrane and subsequent swelling of the matrix with rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane leads to release of intermembrane proteins, such as endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor, and their translocation to the nucleus with nuclear DNA fragmentation (Bajt et al. 2006 and 2008; Cover et al. 2005). The massive mitochondrial dysfunction and nuclear DNA damage are the main causes of necrotic cell death (Gujral et al. 2002). The release of cellular contents during necrosis includes a number of molecules, so-called damage-associated molecular patterns, which can activate Toll-like receptors on macrophages and induce cytokine formation (Antoine et al. 2009; Bianchi 2007; Dragomir et al. 2011; Martin-Murphy et al. 2010). These inflammatory mediators activate neutrophils and monocytes leading to the recruitment of these leukocytes into the liver (Scaffidi et al. 2002). The physiological function of these recruited inflammatory cells is to remove cell debris and to prepare the tissue for repair (Holt et al. 2008; Lawson et al. 2000b). On the other hand, neutrophils and macrophages can also potentially aggravate the injury, as well established in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (Jaeschke et al. 1990) and obstructive cholestasis (Gujral et al. 2003). However, this topic is highly controversial for APAP hepatotoxicity with the preponderance of evidence supporting a role of the inflammatory response in regeneration rather than cell injury, as previously reviewed (Jaeschke et al. 2012b). Importantly, evidence in humans also suggests a role for infiltrating mononuclear cells and neutrophils in the repair process and not in the injury mechanism (Antoniades et al. 2012; Williams et al. 2014).

Figure 2. Mechanism of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity.

High dose of acetaminophen (APAP) results in the formation of the reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in hepatocytes. NAPQI depletes the glutathione (GSH) pool and binds to cysteine sulfhydryl groups of proteins thereby forming APAP-protein adducts. This initiates mitochondrial oxidant stress and peroxynitrite formation. The early oxidant stress triggers activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) that ultimately cause c-jun N-terminal kinase activation (p-JNK), which then translocates to mitochondria to further exacerbate the mitochondrial oxidant stress. The oxidant stress promotes the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore opening, resulting in the collapse of the membrane potential and cessation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis. Early formation of a Bax-based pore in the outer mitochondrial membrane and subsequent swelling of the matrix with rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane leads to release of intermembrane proteins, such as endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and their translocation to the nucleus with nuclear DNA fragmentation. The massive mitochondrial dysfunction and nuclear DNA damage are the main causes of necrotic cell death.

In addition to the accumulating knowledge about the injury mechanisms, it has been recognized that any cell under stress responds by upregulating defense mechanisms. This includes induction of anti-oxidant genes, such as superoxide dismutase 2, thioredoxin, heme oxygenase 1 and glutamate-cysteine ligase, through the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2 like 2 (Klaassen and Reisman 2010). Furthermore, the activation of autophagy leads to the removal of damaged mitochondria, which limits APAP-induced cell death (Ni et al. 2012). Overall, the cell fate is decided between the extent of the pro-death mechanisms and the protective stress response. The cell dies unless the adaptive mechanisms are strong enough to counteract the cell death mechanism. This is both a question of time as well as of location within the hepatic lobules (Ni et al. 2013). Another important defense mechanism is the entry into the cell cycle, which prepares the cell for division and tissue regeneration (Apte et al. 2009; Mehendale 2005). Given the complex time-dependent mechanisms of metabolic activation, pro-cell death mechanisms, adaption, inflammatory response and regeneration, it is imperative to always evaluate multiple time points when using this model. Currently, the most common problem with the APAP model is the use of a single late time point and drawing mechanistic conclusions by measuring multiple parameters. This does not allow distinguishing cause and effect. Indeed, any parameter can normalize as a consequence of reduced liver injury without reflecting a mechanistic cause. One of the most effective ways to prevent APAP toxicity is to interfere with the initial step of metabolic activation. Many solvents, such as dimethyl sulfoxide or ethanol, used to dissolve agents with limited water solubility effectively, compete with APAP for CYP metabolism even at very low doses (Jaeschke et al. 2006; Park et al. 1988; Sato and Lieber 1981; Yoon et al. 2006). Extracts from plants and other sources contain numerous chemicals that can act as CYP inhibitors (Jiang et al. 2015), but are rarely tested for this effect. As a result, most of the mechanistic conclusions are questionable. Thus, if pharmacological interventions or genetically modified animals or cells are being used, it is necessary to assess metabolic activation of APAP by either measuring protein adducts directly or by assessing GSH depletion during the first 30 minutes after APAP treatment (Jaeschke et al. 2011). In addition, intracellular mechanisms of cell death in hepatocytes should be assessed in the time frame of 2 and 12 hours, while inflammation develops between 6 and 24 hours and regeneration occurs during the period of 24 and 72 hours (Jaeschke et al. 2012b).

Next to the animal model, cultures of hepatocytes are valuable tools to investigate the cellular events related to APAP hepatotoxicity at a more mechanistic level, which is often not possible in vivo. In view of avoiding interspecies difference issues, human-based in vitro models are preferred (Jemnitz et al. 2008; McGill et al. 2011; Schulze et al. 2012; Smith 1991; Xie et al. 2014). In this light, primary human hepatocytes provide a good reflection of the in vivo situation. Mechanisms of APAP-induced cell death in primary human hepatocytes and in livers of APAP-overdosed patients are very similar, which is not always the case for animal-based systems (McGill et al. 2012b; Xie et al. 2014). However, relatively high concentrations of APAP are needed to trigger toxicity in this in vitro setting compared to concentrations found in serum of patients with acute liver failure (Jemnitz et al. 2008; Routledge et al. 1998). Furthermore, the use of primary human hepatocytes is limited by scarcity and difficulty in obtaining human material of sufficient quality. The latter highly depends on lifestyle and health status of donors, which is often compromised, as these cells are typically obtained from liver biopsies of patients suffering from liver disease or from postmortem donated livers unsuitable for transplantation. In addition, inter-individual variability in toxicity due to genetic, environmental and age differences of the donors is manifested in freshly isolated human hepatocytes (Donato et al. 2008; Lecluyse and Alexandre 2010; LeCluyse et al. 2005). To overcome the availability, quality and inter-individual variability issues of human cells, numerous studies have been conducted using APAP-exposed primary rodent hepatocytes, with the best results obtained with those originating from mice (Adamson and Harman 1993; Bajt et al. 2004; Burcham and Harman 1991; Burke et al. 2010; Kon et al. 2004 and 2007; Ni et al. 2012; Reid et al. 2005; Shen et al. 1992). Although the in vivo rat model has limited relevance for humans compared to mice, similar concentration-dependent GSH depletion, oxidant stress and cytotoxicity are observed in their corresponding hepatocyte cultures (Ellouk-Achard et al. 1995; McGill et al. 2012b; Rousar et al. 2009; Yang and Salminen 2011). Likewise, cultured mouse and human hepatocytes show comparable GSH depletion, mitochondrial protein adduct formation, p-JNK activation and necrosis, albeit occurring at earlier time points and with overall lower protein binding in the rodent in vitro setting. In line with this finding, N-acetylcysteine treatment of mouse hepatocytes, unlike their human counterparts, is not effective beyond 2 hours after APAP exposure, again highlighting the more accelerated pathophysiology in the murine system (McGill et al. 2012b and 2013; Xie et al. 2014).

Popular and more users-friendly substitutes for primary human hepatocytes include liver cell lines isolated from human hepatomas, such as HepG2, Hep3B, Huh7, Fa2N4 and HepaRG cells. Cell lines provide an unlimited supply of identical cells with infinite growth capacity, which favors experimental robustness and reproducibility. However, cell lines may present genetic instability and, originating from liver cancer tissue, are not always representative of the physiological in vivo situation (Castell et al. 2006; Donato et al. 2008 and 2013; Godoy et al. 2013). In addition, most hepatic cell lines show only low or partial expression of biotransformation enzymes, including CYP enzymes, compared to freshly isolated primary hepatocytes or intact liver (Castell et al. 2006; Harris et al. 2004; Rodríguez-Antona et al. 2002; Wilkening et al. 2003). A notable exception lies with HepaRG cells, which functionally express the most important drug transporting and metabolizing enzymes at an acceptable and stable level similar to primary human hepatocytes (Aninat et al. 2006; Guillouzo et al. 2007; Kanebratt and Andersson 2008a and 2008b). HepaRG cells have proven their power in the in vitro investigation of APAP-induced liver toxicity on several occasions. Indeed, the mechanisms involved in this toxicological process in HepaRG cells resemble those in rodent hepatocytes and include protein adduct formation, mitochondrial oxidative stress, peroxynitrite formation and loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential, ultimately resulting in necrosis (McGill et al. 2011; Tobwala et al. 2014). In addition, the time course of cell death in APAP-treated HepaRG cells is very similar to what is observed in clinical patients. This underscores the reliability and usefulness of the HepaRG cell line as an in vitro model to study the mechanisms of APAP-related hepatotoxicity, which is much less the case for other human hepatoma cell lines. Nevertheless, APAP also induces toxicity in other liver cancer cell lines, such as HepG2, Hep3B and Huh7 cells, yet at higher concentrations and mainly driven by apoptosis (Boulares et al. 2002; Kass et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2012; Manov et al. 2004). In contrast to primary hepatocytes, there is little protein adduct formation, GSH depletion or mitochondrial dysfunction (Dai and Cederbaum, 1995; McGill et al. 2011). This suggests that the mechanism of APAP-related liver toxicity in these hepatoma cell lines is independent of reactive metabolite formation, which is not suitable for the human disease process and may not be therapeutically relevant.

3. D-galactosamine/endotoxin-based model

Rodents are relatively resistant to even high doses of ET, which may cause death due to hypotensive shock, but no liver injury. However, co-administration of at least 300 mg/kg Gal (Figure 3.) dramatically sensitizes rodents to ET, resulting in extensive liver injury and death (Galanos et al. 1979). The pathophysiology starts with the binding of ET to Toll-like receptor 4 on Kupffer cells, which triggers the transcriptional activation of cytokine genes, in particular TNFα, within 30 to 90 minutes (Figure 4.) (Schlayer et al. 1988; Tiegs et al. 1989). TNFα is a potent activator of neutrophils (Bajt et al. 2001a) and is mainly responsible for neutrophil recruitment into liver sinusoids after ET treatment (Schlayer et al. 1988). TNFα is also the main inducer of various adhesion molecules, such as the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on endothelial cells and hepatocytes (Essani et al. 1995), the vascular adhesion molecule 1 on endothelial cells (Essani et al. 1997), selectins on endothelial cells (Essani et al. 1998; Lawson et al. 2000a) and chemokines in hepatocytes (Dorman et al. 2005) in the Gal/ET model. Some of these adhesion molecules are critical for neutrophil extravasation and cytotoxicity (Figure 4.) (Jaeschke 2006). Mechanisms of neutrophil involvement in hepatocyte cytotoxicity have been studied in co-cultures of primary hepatocytes and activated neutrophils (Ganey et al. 1994; Harbrecht et al. 1993; Mavier et al. 1988). However, the conditions used do not always accurately reflect the in vivo situation. The investigators have used activated human neutrophils next to control rat hepatocytes (Harbrecht et al. 1993; Mavier et al. 1988). Thus, human neutrophils may not recognize chemokines released from rat or mouse hepatocytes. In addition, contact between neutrophils and target cells seems not to be required for cell injury in vitro compared to the in vivo situation, as conditioned medium of activated neutrophils is as effective in killing hepatocytes as the neutrophils themselves (Ho et al. 1996).

Figure 3. Chemical structure of D-galactosamine.

Figure 4. Pathophysiology of D-galactosamine/endotoxin-based liver injury.

Endotoxin (ET) binds to Tolllike receptor 4 (TLR-4) on Kupffer cells, which triggers transcriptional activation of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα). This results in activation of neutrophils, whereby TNFα is mainly responsible for neutrophil recruitment into the liver sinusoids. Furthermore, TNFα induces various adhesion molecules, such as the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), the vascular adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and selectin chemokines in hepatocytes and endothelial cells. Some of these adhesion molecules are critical for neutrophil extravasation. High dose of D-galactosamine (Gal) depletes the cellular uridine triphosphate and inhibits mRNA synthesis, such as of anti-apoptotic genes, in hepatocytes. This results in activation of the caspase cascade and DNA fragmentation. Caspase activation is also caused by TNFα-induced apoptosis involving the TNFα receptor 1 (TNFα-R1) and caspase activation.

Cell death in the Gal/ET model is also caused by TNFα-induced apoptosis involving the TNFα receptor 1 (Leist et al. 1995) and caspase activation (Figure 4.) (Jaeschke et al. 1998; Künstle et al. 1997). The default signaling of the TNFα receptor is activation of nuclear factor kappa beta resulting in the induction of pro-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic genes (Liedtke and Trautwein 2012). However, administration of a high dose of Gal depletes the cellular uridine triphosphate pool and inhibits mRNA synthesis in hepatocytes for several hours (Decker and Keppler 1974). This prevents the synthesis of anti-apoptotic genes in hepatocytes and allows apoptotic signaling with activation of the caspase cascade and DNA fragmentation to proceed (Figure 4.). Caspase activation and DNA damage is detectable as early as 5 hours after Gal/ET treatment. Due to the mitochondrial amplification of the pro-apoptotic signaling, inhibition of any caspases with the respective suicide substrate is highly effective in preventing apoptotic cell death (Bajt et al. 2001b; Jaeschke et al. 1998; Künstle et al. 1997). Because of the fact that Gal is metabolized only in hepatocytes (Decker and Keppler 1974), Gal/ET induces apoptotic cell death exclusively in parenchymal cells (Jaeschke et al. 1998). Therefore, Gal-induced apoptosis in vitro has been studied in monocultures of primary rodent hepatocytes and human hepatoma cells (Bao and Liu 2010; Kucera et al. 2006a and 2006b). However, as Kupffer cell activation and production of TNFα are critical events in Gal/ET-induced hepatotoxicity (Stachlewitz et al. 1999), co-cultures of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells seem more appropriate to study Gal/ET hepatotoxicity in vitro (Abou-Elella et al. 2002; Ma et al. 2009).

Although apoptotic cell death and inflammation were recognized as features of the Gal/ET model, the interaction between these mechanisms remains uncertain. However, when assessing neutrophil recruitment in this in vivo model, it is clear that neutrophils are only cytotoxic when they extravasate from the sinusoids and migrate into the parenchyma (Chosay et al. 1997). Interestingly, this transmigration and cytotoxicity can be completely prevented when apoptotic cell death is inhibited (Jaeschke et al. 1998; Lawson et al. 1998), suggesting that, contrary to the central dogma that apoptosis does not cause inflammation, apoptotic cell death is indeed the trigger for neutrophil extravasation. This was further confirmed by studies indicating that neutrophils accelerate the injury process by killing cells in the early stages of apoptosis rather than healthy cells. The neutrophil-mediated cell death is mainly dependent on reactive oxygen formation by neutrophils through the enzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (Gujral et al. 2004), which generates intracellular oxidant stress in the target cells (Jaeschke et al. 1999). Interestingly, hepatocytes also generate extensive amounts of CXC chemokines, but these neutrophil chemo-attractants are not responsible for the neutrophil extravasation and toxicity in this model (Dorman et al. 2005).

The Gal/ET model is thus useful to study TNFα-mediated apoptotic signaling mechanisms in hepatocytes and inflammatory liver injury in vivo, including cytokine and chemokine formation, adhesion molecule expression and mechanisms of neutrophil-mediated cell death. Fundamental new insight into mechanisms of liver injury was obtained with this model. In addition, it is a popular model to test potential hepatoprotective chemicals and natural products. However, for the accurate interpretation of any data obtained with this model, it is important to keep the time line of events in mind. To assess the effect of therapeutic interventions in this model, it is important to evaluate the effect of the drug or chemical on TNFα formation at 60 to 90 minutes after Gal/ET treatment, to assess early neutrophil accumulation at 4 hours, apoptosis at 5 to 6 hours and neutrophil-induced aggravation of the apoptotic injury at 6 to 8 hours. These times may vary slightly in different strains of mice. Despite the reproducibility of the injury mechanisms in this model, the model does not mimic a specific human pathophysiology, but needs to be considered a model for TNFα-mediated apoptosis and inflammatory neutrophil-mediated liver injury. In vivo, death is caused mainly by hypovolemic shock due to severe hemorrhage after development of gaps in sinusoidal endothelial cells (Ito et al. 2006) and not acute liver failure.

4. Fas ligand-based model

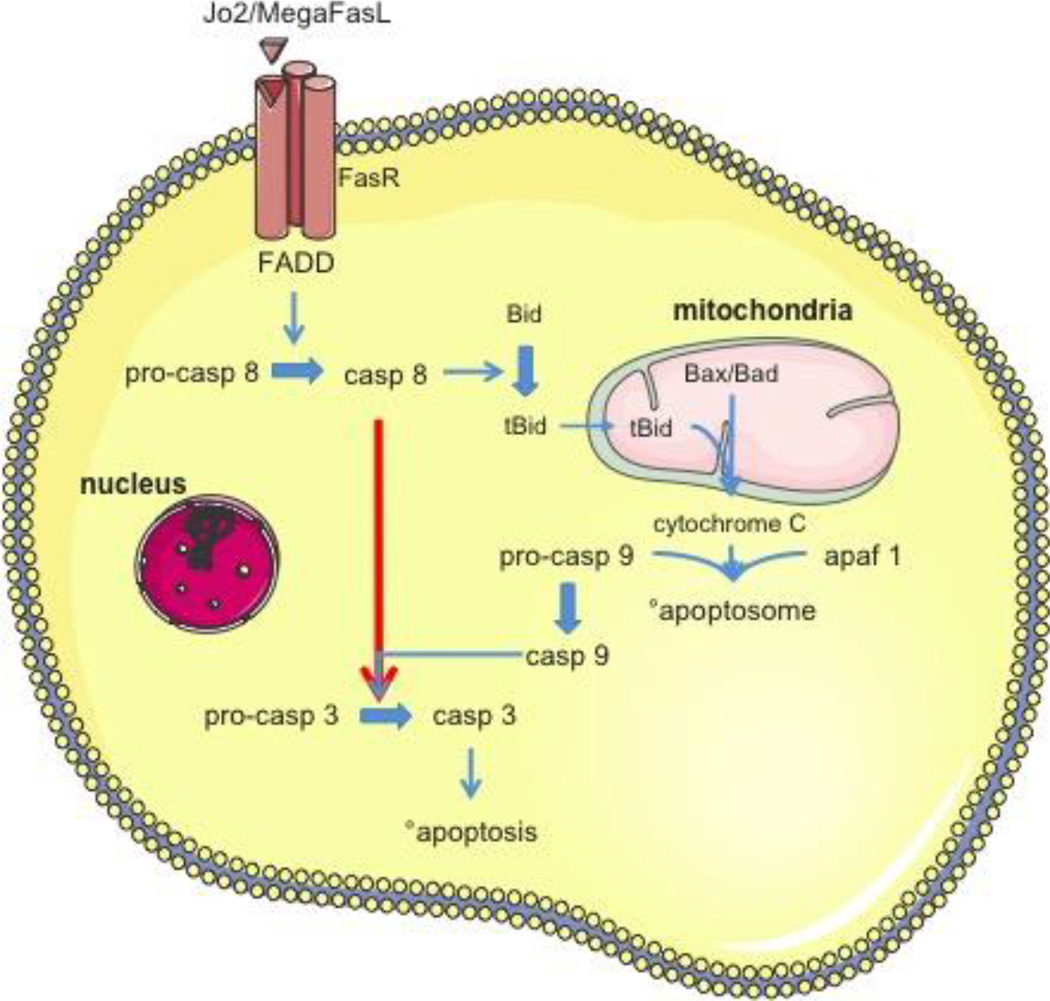

The Fas receptor is a member of the TNF receptor family with a death domain that is able to assemble a death-inducing signaling complex to induce caspase activation and apoptosis (Figure 5.) (Itoh et al. 1991; Strasser et al. 2009; Suda et al. 1993; Trauth et al. 1989; Yonehara et al. 1989). Thus, all cells that express the Fas receptor can undergo apoptosis upon binding of the (FasL) or any other receptor agonist. One of the most widely used experimental models of hepatocellular apoptosis in vivo includes administration of 0.5 to 0.6 mg/kg of the agonistic Fas receptor antibody Jo2 to mice (Lacronique et al. 1996; Lawson et al. 1998; Ogasawara et al. 1993; Schüngel et al. 2009). In addition, the hexameric form of soluble FasL, called MegaFasL, can trigger massive apoptosis and liver failure in mice at a concentration of 0.05 mg/kg (Greaney et al. 2006; Holler et al. 2003; Schüngel et al. 2009). The underlying mechanism involves activation of caspase 8, Bid cleavage and translocation of the truncated Bid to mitochondria, cytochrome c release with activation of the apoptosome, caspase 9 and caspase 3 activation (Figure 5.) (Bajt et al. 2000; Li et al. 1998; Stennicke et al. 1998; Yin et al. 1999; Zou et al. 1999). Although Bid deficiency can inhibit Fas-induced apoptosis in liver (Yin et al. 1999), inhibitors of both caspase 8 and caspase 3 are equally effective (Bajt et al. 2000 and 2001b). The fact that inhibition of the downstream effector caspase 3 also attenuates the activation and processing of the initiator caspase 8 suggests that the activation of the caspase cascade is not a linear process. Indeed, this also includes mitochondrial amplification loops, where caspase 3 not just cleaves downstream substrates, but may also further promote the processing and activation of caspase 8 (Bajt et al. 2000).

Figure 5. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis in type I and type II cells.

Binding of Jo2 or MegaFasL to the Fas ligand receptor (FasR) with a so-called ‘death domain’ (FADD) activates caspase (casp) 8. In type I cells (red arrow), the activation of casp 8 is sufficient to directly activate effector caspase 3. In contrast, in type II cells (blue arrows) casp 8 activation triggers Bid cleavage and truncated Bid (tBid) translocation to mitochondria. Together with Bax and Bad, tBid causes the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization with release of cytochrome c. The latter, together with pro-casp 9 and apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (apaf 1), form the apoptosome, which activates casp 9. This leads to drastically enhanced casp 3 activation, followed by induction of apoptosis.

The agonistic Fas antibody Jo2 can dose-dependently induce apoptosis in both hepatocytes and in sinusoidal endothelial cells (Bajt et al. 2000). Thus, during the initial period of less than 1 hour, the process is selective apoptosis with the characteristic morphological modifications, such as cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation and apoptotic bodies formation, and biochemical changes, including caspase processing and increased enzyme activities and nuclear DNA fragmentation, in the absence of release of liver enzymes, in particular alanine aminotransferase (ALT). However, the massive apoptosis deteriorates quickly into secondary necrosis with extensive ALT release, hemorrhage and eventually death of the animal (Bajt et al. 2000; Ogasawara et al. 1993). The important distinction between a primary necrotic mechanism, such as APAP hepatotoxicity, and secondary necrosis, is that there is still massive caspase activation and a caspase inhibitor will effectively eliminate both apoptotic cell death and secondary necrosis, as previously reviewed (Jaeschke et al. 2004). As has been pointed out with other models of liver injury, the agonistic Fas antibody can induce extensive liver injury and eventually death of the animal. However, the cause of death is not acute liver failure as in patients, but the extensive hemorrhage due to endothelial cell apoptosis and the resulting hypovolemic shock.

There are generally 2 types of cells with respect to receptor-mediated apoptotic signaling (Figure 5.) (Scaffidi et al. 1998). In type I cells, the activation of initiator caspase 8 and caspase 10 is sufficient to directly activate effector caspase 3 and caspase 6, and cause apoptotic cell death. T-cells are prototypical type I cells (Scaffidi et al. 1999). In contrast, in type II cells, the initial signal by the receptor is insufficient to trigger enough effector caspase activation that results in cell death. Thus, caspase 8 activation triggers Bid cleavage and truncated Bid translocation to the mitochondria to cause together with the other B-cell lymphoma 2 family members Bax and Bad the mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (Green and Kroemer 2004; Strasser et al. 2009; Youle and Strasser 2008). This results in cytochrome c release from mitochondria and apoptosome formation with caspase 9 activation, which drastically enhances caspase 3 activation. This signaling loop through the mitochondria generates enough of the activation of effector caspases to initiate cell death. Based on both TNFα receptor-mediated and agonistic Fas antibody-mediated apoptosis, it is generally believed that hepatocytes are type II cells. However, this hypothesis has been challenged, as apoptosis induced by the MegaFasL in vivo showed that hepatocytes can also behave as type I cells if the strength of the activating signal at the receptor is high enough to cause sufficient initiator caspase activation to fully activate the caspase cascade (Schüngel et al. 2009). In addition, primary cultured mouse hepatocytes were found to switch to a type I cell behavior depending on extracellular matrix adhesion. This effect seems to be specific for Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis (Walter et al. 2008). Nevertheless, under pathophysiological relevant conditions in vivo, hepatocytes appear to preferentially behave as type II cells.

In vitro cultures of hepatocytes are often exposed to FasL or Jo2 to induce the full course of apoptosis. As apoptotic cells are rapidly engulfed by neighboring phagocytes, they are barely detectable in vivo. During in vitro experimentation, however, the late apoptotic phase is typically followed by secondary necrosis (Gómez-Lechón et al. 2002; Raffray and Cohen 1997). Immortalized cell lines are frequently used as experimental tools in in vitro apoptosis research. It should be kept in mind that these cells are often derived from tumors and have typically acquired high resistance against apoptosis (Lei et al. 2007; McGill et al. 2011; Schulze-Bergkamen et al. 2003). Primary hepatocytes may offer a better alternative, as they display in vivo-like sensitivity to apoptosis, at least during short-term cultivation regimes (Schulze-Bergkamen et al. 2003). Among the numerous experimental strategies that have been followed to provoke apoptotic cell death in primary hepatocyte cultures, the use of Fas triggers is a most reasonable approach, as it directly activates the physiological pathway (Vinken et al. 2009). Monoclonal agonistic antibodies directed against the Fas receptor are frequently used in primary hepatocyte cultures. However, unlike FasL, binding of the antibody to the Fas receptor does not result in the onset of pro-apoptotic signaling per se (Fadeel et al. 1997; Legembre et al. 2003; Thilenius et al. 1997). In addition, Fas-mediated apoptosis induced by agonistic antibodies becomes typically manifested to a lesser extent compared to the in vivo situation (Nagata 1999; Ni et al. 1994). For this reason, Fas antibodies are often combined with inhibitors of protein production or gene expression, such as cycloheximide and actinomycin D, respectively (Nagata 1999; Ni et al. 1994; Rouquet et al. 1996). A more rationalized strategy that resembles the natural Fas pathway is the use of FasL as such (Fu et al. 2004; Reinehr et al. 2002; Vinken et al. 2009). FasL can also be presented to hepatocytes by cultivation partners. In this regard, a co-culture system consisting of primary mouse hepatocytes and 3T3 fibroblasts stably transfected with FasL was found to be an effective in vitro model to study hepatocellular cell death, since the entire hepatocyte population undergoes apoptosis 24 hours after its establishment (Schlosser et al. 2000).

Activation of the Fas receptor with Jo2 or FasL thus is an effective model of receptor-mediated apoptosis and secondary necrosis that is useful to study apoptotic signaling mechanisms and interventions that potentially effect apoptotic cell death in vivo and in vitro. Interestingly, Jo2 can also trigger CXC chemokine formation and inflammation independent of nuclear factor kappa beta activation, but dependent on caspases and the transcription factor activator protein 1 (Faouzi et al. 2001). Although the originally used high doses of Jo2 in vivo can cause apoptosis within 45 to 90 minutes followed by secondary necrosis, and hemorrhage and death within 3 to 4 hours, lower doses can substantially delay the injury process and reduce mortality. The advantage of this model, as compared to the Gal/ET system, is that Jo2 or FasL directly activate the Fas receptor, with no need for generation of different mediators, and that the default response of Fas receptor activation is apoptotic cell signaling, with no need for the use of transcriptional inhibitors.

5. Concanavalin A-based model

First recognized by Tiegs and colleagues, ConA triggers massive liver injury in mice (Tiegs et al. 1992). The preferred study design is the use of 20 mg/kg ConA, where the injury process is followed up to 8 to 10 hours. ConA is a bean-derived lectin, which induces T-cell-mediated liver damage dependent mainly on CD4+ T-cells, but not their CD8+ counterparts (Tiegs et al. 1992). The initiating event of the pathophysiology is the early binding of ConA to sinusoidal endothelial cells. This recruits CD4+ T-lymphocytes, which cause damage to endothelial cells (Knolle et al. 1996). The damage to sinusoidal endothelial cells facilitates binding of ConA to Kupffer cells, in turn causing extensive TNFα formation (Schümann et al. 2000). The liver infiltrating CD4+ T-lymphocytes are the main source of interferon γ (IFNγ), but also contribute to the formation of TNFα and other cytokines (Cao et al. 1998). Both TNFα and IFNγ are critical mediators of ConA-induced cytotoxicity (Küsters et al. 1996). Interestingly, despite the involvement of T-lymphocytes and TNFα in the mechanism of liver injury, the mode of cell death in this model appears to be not apoptosis, but rather necrosis. ConA does not activate caspases and pancaspase inhibitors do not protect (Künstle et al. 1999; Ni et al. 2008). Massive release of ALT and morphological characteristics support necrosis as the main mechanism of cell death. Recently, the involvement of receptor-interacting protein kinases 1 and 3 in ConA-mediated liver injury has been suggested, which would indicate a programmed necrosis process. However, conflicting data regarding the effect of the receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 inhibitor necrostatin were reported (Deutsch et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2013). It was shown that TNFα and IFNγ can synergistically activate a number of adhesion molecules on sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells as well as chemokines in hepatocytes (Jaruga et al. 2004). This may explain the infiltration of additional leukocytes, such as neutrophils, into the liver (Jaruga et al. 2004). Neutrophils have been suggested to contribute to ConA-induced liver injury by direct cytotoxicity and indirectly also by promoting T-cell recruitment (Bonder et al. 2004). Neutrophil cytotoxicity in the liver is dependent on hypochlorous acid and is caused by necrosis (Jaeschke 2006).

The ConA model of T-cell-mediated liver injury thus is considered a relevant model of autoimmune hepatitis, viral hepatitis and related acute liver failure (Tsutsui and Nishiguchi 2014; Wang et al. 2012). However, the pathophysiology and, in particular, the immunology of this model are complex and only partially understood even in mice (Hammerich et al. 2011). The relevance of many aspects of the mechanisms of ConA-induced liver injury in mice for human diseases remains unclear. In particular, the ConA model is a very acute model of liver injury that can, due to severe hemorrhage, lead to high mortality. However, as with the other models, may mimic aspects of the injury mechanism, but do not really reflect acute liver failure in humans. Even for the injury mechanisms, the well-known differences between murine and human immunology need to be considered when interpreting findings with this model. In addition, differences in mouse strains used, dose and time of administration of immunological reagents, and minor sequence differences all can have a major impact on the pathophysiology resulting in different and even opposite results (Abe et al. 2005; Heymann et al. 2015; Jiang et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2010). Therefore, careful study design and cautious interpretation of experimental findings are critical to improve the insight into the pathophysiology.

6. Conclusions and perspectives

Hepatotoxicity can be experimentally induced by several chemicals in vivo as well as in vitro, all of which will trigger specific aspects of acute liver failure in human patients (Table 1.). The assumption is that mechanistic findings using these experimental models can be translated to the human pathophysiology of liver diseases and will eventually result in new therapies. However, whereas some models mimic closely the entire process observed in patients, such as the murine model of APAP hepatotoxicity, other models only simulate some events of the human disease. Although significant progress has been made in the last few years, there is clearly a need to further improve insight into the molecular mechanisms of liver injury and cell death in all experimental models. Importantly, it is also necessary to scrutinize the mechanisms of the human disease in order to understand how much of the data in the animal model can be extrapolated to the human pathophysiology. Although it appears that the murine APAP model of acute liver injury and repair is very close to what is observed in patients (McGill and Jaeschke 2014), there are still large gaps in knowledge regarding the animal model, in understanding the human disease and in the translation of the model to the human disease. A way to avoid interspecies difference issues is the use of human-based in vitro systems, of which cultures of primary human hepatocytes are considered as the gold standard. However, a flaw of the commonly used monocultures of these cells is the progressive loss of their functional status, including deterioration of metabolic competence. This dedifferentiation process can be counteracted, at least in part, by a number of strategies that aim at mimicking the natural hepatocyte micro-environment in vitro, such as by seeding between 2 layers of extracellular matrix components (Dunn et al. 1991; Hughes et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2010; Rowe et al. 2010; Tuschl et al. 2009; Zeisberg et al. 2006) or by co-cultivation with nonparenchymal liver cells (Bale et al. 2014; Bhatia et al. 1999; Goulet et al. 1988; Kasuya et al. 2011; Kim and Rajagopalan 2010; Morin and Normand 1986; Sunman et al. 2004; Tukov et al. 2006). As a matter of fact, hepatic nonparenchymal cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of acute liver failure, in particular by secreting cytokines (DeLeve et al. 1997; Jaeschke et al. 2012b; Liu et al. 2004; Liu and Kaplowitz 2006; Ochi et al. 2004). This should be appropriately reproduced in vitro either by co-culturing hepatocytes with nonparenchymal liver cells or by direct exposure of hepatocytes to pro-inflammatory cytokines. Alternatively, precision-cut liver slices are appropriate systems to study hepatotoxicity in vitro, as they retain normal tissue architecture and the complete set of complex cellular interactions that occur in vivo (Hadi et al. 2013; Neyrinck et al. 1999). However, this in vitro model is only fully metabolically competent during 6 to 24 hours. In conclusion, the chemical-induced in vitro and in vivo experimental models of hepatotoxicity related to acute liver failure discussed in this paper all have a number of strengths and weaknesses. Alternatively, other chemicals can be used to induce acute liver injury, including thioacetamide (Chieli and Malvaldi 1984; Hajovsky et al. 2012; Peeling et al. 1993; Staňková et al. 2010), α-amanitin/ET (Takada et al. 2003; Takada et al. 2001), azoxymethane (Bélanger et al. 2006; Matkowskyj et al. 1999) and carbon tetrachloride (Pilichos et al. 2004; Taniguchi et al. 2004; van Leenhoff et al. 1974). The advantages and disadvantages of these models have been reviewed previously (Bélanger and Butterworth 2005; Tuñón et al. 2009). Overall, further improvement in understanding the individual models as well as the human liver disease as such should be prioritized in the upcoming years. Until significant progress has been made, translating any data obtained with these in vivo and in vitro models to human beings need to be done with extreme caution.

Highlights.

The murine APAP model is very close to what is observed in patients.

The Gal/ET model is useful to study TNFα-mediated apoptotic signaling mechanisms.

Fas receptor activation is an effective model of apoptosis and secondary necrosis.

The ConA model is a relevant model of auto-immune hepatitis and viral hepatitis.

Multiple time point evaluation needed in experimental models of acute liver injury.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the grants of Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT), the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant 335476), the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO grants G009514N and G010214N) and the University Hospital of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel-Belgium (“Willy Gepts Fonds” UZ-VUB). Work in the author’s laboratory (H.J.) was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK102142 and R01 AA12916, and by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR021940) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P20 GM103549) from the National Institutes of Health.

List of abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- APAP

acetaminophen

- ConA

concanavalin A

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- ET

endotoxin

- FasL

Fas ligand

- Gal

D-galactosamine

- GSH

glutathione

- IFNγ

interferon γ

- NAPQI

N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine

- p-JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase activation

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abe K, Ohira H, Kobayashi H, Rai T, Saito H, Takahashi A, Sato Y. Role of CpG ODN in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis in mice. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2005;51:41–49. doi: 10.5387/fms.51.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Elella AM, Siendones E, Padillo J, Montero JL, De la Mata M, Muntane Relat J. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and nitric oxide mediate apoptosis by D-galactosamine in a primary culture of rat hepatocytes: exacerbation of cell death by cocultured Kupffer cells. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:791–799. doi: 10.1155/2002/986305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson GM, Harman AW. Oxidative stress in cultured hepatocytes exposed to acetaminophen. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;45:2289–2294. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano E, Rundgren M, Harvison PJ, Nelson SD, Moldéus P. Mechanisms of N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine cytotoxicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;28:306–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aninat C, et al. Expression of cytochromes P450, conjugating enzymes and nuclear receptors in human hepatoma HepaRG cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:75–83. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine DJ, et al. High-mobility group box-1 protein and keratin-18, circulating serum proteins informative of acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis in vivo . Toxicol Sci. 2009;112:521–531. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniades CG, et al. Source and characterization of hepatic macrophages in acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure in humans. Hepatology. 2012;56:735–746. doi: 10.1002/hep.25657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte U, Singh S, Zeng G, Cieply B, Virji MA, Wu T, Monga SP. Beta-catenin activation promotes liver regeneration after acetaminophen-induced injury. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1056–1065. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Cover C, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Nuclear translocation of endonuclease G and apoptosis-inducing factor during acetaminophen-induced liver cell injury. Toxicol Sci. 2006;94:217–225. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Effects of CXC chemokines on neutrophil activation and sequestration in hepatic vasculature. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001a;281:G1188–G1195. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Farhood A, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Mitochondrial bax translocation accelerates DNA fragmentation and cell necrosis in a murine model of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:8–14. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.129445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Knight TR, Lemasters JJ, Jaeschke H. Acetaminophen-induced oxidant stress and cell injury in cultured mouse hepatocytes: protection by N-acetyl cysteine. Toxicol Sci. 2004;80:343–349. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Lawson JA, Vonderfecht SL, Gujral JS, Jaeschke H. Protection against Fas receptor-mediated apoptosis in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells by a caspase-8 inhibitor in vivo: evidence for a postmitochondrial processing of caspase-8. Toxicol Sci. 2000;58:109–117. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/58.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajt ML, Vonderfecht SL, Jaeschke H. Differential protection with inhibitors of caspase-8 and caspase-3 in murine models of tumor necrosis factor and Fas receptor-mediated hepatocellular apoptosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001b;175:243–252. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale SS, et al. Long-term coculture strategies for primary hepatocytes and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells tissue. Eng Part C Methods. 2014;21:413–422. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2014.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao XQ, Liu GT. Involvement of HSP70 in the protection of bicyclol on apoptosis of HepG2 cells intoxicated by D-galactosamine. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2010;12:313–323. doi: 10.1080/10286021003769924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger M, Butterworth RF. Acute liver failure: a critical appraisal of available animal models. Metab Brain Dis. 2005;20:409–423. doi: 10.1007/s11011-005-7927-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger M, Côté J, Butterworth RF. Neurobiological characterization of an azoxymethane mouse model of acute liver failure. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SN, Balis UJ, Yarmush ML, Toner M. Effect of cell-cell interactions in preservation of cellular phenotype: cocultivation of hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells. FASEB J. 1999;13:1883–1900. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan B, et al. Pro-regenerative signaling after acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in mice identified using a novel incremental dose model. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:3013–3025. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonder CS, Ajuebor MN, Zbytnuik LD, Kubes P, Swain MG. Essential role for neutrophil recruitment to the liver in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:45–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulares AH, Zoltoski AJ, Stoica BA, Cuvillier O, Smulson ME. Acetaminophen induces a caspase-dependent and Bcl-XL sensitive apoptosis in human hepatoma cells and lymphocytes. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;90:38–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.900108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burcham PC, Harman AW. Acetaminophen toxicity results in site-specific mitochondrial damage in isolated mouse hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5049–5054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AS, MacMillan-Crow LA, Hinson JA. Reactive nitrogen species in acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial damage and toxicity in mouse hepatocytes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:1286–1292. doi: 10.1021/tx1001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, Batey R, Pang G, Russell A, Clancy R. IL-6, IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha production by liver-associated T cells and acute liver injury in rats administered concanavalin A. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:542–549. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castell JV, Jover R, Martinez-Jimenez CP, Gomez-Lechon MJ. Hepatocyte cell lines: their use, scope and limitations in drug metabolism studies. Expert Opin Drug Metabol Toxicol. 2006;2:183–212. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieli E, Malvaldi G. Role of the microsomal FAD-containing monooxygenase in the liver toxicity of thioacetamide S-oxide. Toxicology. 1984;31:41–52. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(84)90154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chosay JG, Essani NA, Dunn CJ, Jaeschke H. Neutrophil margination and extravasation in sinusoids and venules of liver during endotoxin-induced injury. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G1195–G1200. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran GB, Racz WJ, Smith CV, Mitchell JR. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on acetaminophen covalent binding and hepatic necrosis in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985a;232:864–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran GB, Todd EL, Racz WJ, Hughes H, Smith CV, Mitchell JR. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on the disposition and metabolism of acetaminophen in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985b;232:857–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran GB, Wong BK. Role of glutathione in prevention of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by N-acetyl-L-cysteine in vivo: studies with N-acetyl-D-cysteine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover C, Mansouri A, Knight TR, Bajt ML, Lemasters JJ, Pessayre D, Jaeschke H. Peroxynitrite-induced mitochondrial and endonuclease-mediated nuclear DNA damage in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:879–887. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin DC, Miwa GT, Lu AY, Nelson SD. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine: a cytochrome P-450-mediated oxidation product of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:1327–1331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DC, Potter WZ, Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR. Species differences in hepatic glutathione depletion, covalent binding and hepatic necrosis after acetaminophen. Life Sci. 1974;14:2099–2109. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(74)90092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K, Keppler D. Galactosamine hepatitis: key role of the nucleotide deficiency period in the pathogenesis of cell injury and cell death. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1974:77–106. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeve LD, Wang X, Kaplowitz N, Shulman HM, Bart JA, van der Hoek A. Sinusoidal endothelial cells as a target for acetaminophen toxicity. Direct action versus requirement for hepatocyte activation in different mouse strains. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M, et al. Divergent effects of RIP1 or RIP3 blockade in murine models of acute liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1759. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato MT, Jover R, Gómez-Lechón MJ. Hepatic cell lines for drug hepatotoxicity testing: limitations and strategies to upgrade their metabolic competence by gene engineering. Curr Drug Metab. 2013;14:946–968. doi: 10.2174/1389200211314090002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato MT, Lahoz A, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ. Cell lines: a tool for in vitro drug metabolism studies. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:1–11. doi: 10.2174/138920008783331086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman RB, Gujral JS, Bajt ML, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Generation and functional significance of CXC chemokines for neutrophil-induced liver injury during endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G880–G886. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00317.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragomir AC, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Macrophage activation by factors released from acetaminophen-injured hepatocytes: potential role of HMGB1. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;253:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K, Williams CD, McGill MR, Jaeschke H. Lower susceptibility of female mice to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: Role of mitochondrial glutathione, oxidant stress and c-jun N-terminal kinase. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;281:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JC, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Long-term in vitro function of adult hepatocytes in a collagen sandwich configuration. Biotechnol Prog. 1991;7:237–245. doi: 10.1021/bp00009a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellouk-Achard S, Mawet E, Thibault N, Dutertre-Catella H, Thevenin M, Claude JR. Protective effect of nifedipine against cytotoxicity and intracellular calcium alterations induced by acetaminophen in rat hepatocyte cultures. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1995;18:105–117. doi: 10.3109/01480549509014315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essani NA, Bajt ML, Farhood A, Vonderfecht SL, Jaeschke H. Transcriptional activation of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 gene in vivo and its role in the pathophysiology of neutrophil-induced liver injury in murine endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 1997;158:5941–5948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essani NA, Fisher MA, Farhood A, Manning AM, Smith CW, Jaeschke H. Cytokine-induced upregulation of hepatic intercellular adhesion molecule-1 messenger RNA expression and its role in the pathophysiology of murine endotoxin shock and acute liver failure. Hepatology. 1995;21:1632–1639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essani NA, Fisher MA, Simmons CA, Hoover JL, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Increased P-selectin gene expression in the liver vasculature and its role in the pathophysiology of neutrophil-induced liver injury in murine endotoxin shock. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:288–296. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadeel B, Thorpe CJ, Yonehara S, Chiodi F. Anti-Fas IgG1 antibodies recognizing the same epitope of Fas/APO-1 mediate different biological effects in vitro . Int Immunol. 1997;9:201–209. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faouzi S, Burckhardt BE, Hanson JC, Campe CB, Schrum LW, Rippe RA, Maher JJ. Anti-Fas induces hepatic chemokines and promotes inflammation by an NF-kappa B-independent, caspase-3-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49077–49082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipponi F, Mosca F. Animal models of fulminant hepatic failure: need to test liver support devices. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:607–613. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(01)80116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T, et al. Hypothermia inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis of primary mouse hepatocytes in culture. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:667–676. doi: 10.3727/000000004783983495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanos C, Freudenberg MA, Reutter W. Galactosamine-induced sensitization to the lethal effects of endotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:5939–5943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganey PE, Bailie MB, VanCise S, Colligan ME, Madhukar BV, Robinson JP, Roth RA. Activated neutrophils from rat injured isolated hepatocytes. Lab Invest. 1994;70:53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy P, et al. Recent advances in 2D and 3D in vitro systems using primary hepatocytes, alternative hepatocyte sources and non-parenchymal liver cells and their use in investigating mechanisms of hepatotoxicity, cell signaling and ADME. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87:1315–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1078-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Lechón MJ, O’Connor E, Castell JV, Jover R. Sensitive markers used to identify compounds that trigger apoptosis in cultured hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2002;65:299–308. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/65.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet F, Normand C, Morin O. Cellular interactions promote tissue-specific function, biomatrix deposition and junctional communication of primary cultured hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1988;8:1010–1018. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaney P, et al. A Fas agonist induces high levels of apoptosis in haematological malignancies. Leuk Res. 2006;30:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillouzo A, Corlu A, Aninat C, Glaise D, Morel F, Guguen-Guillouzo C. The human hepatoma HepaRG cells: a highly differentiated model for studies of liver metabolism and toxicity of xenobiotics. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;168:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Farhood A, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. Neutrophils aggravate acute liver injury during obstructive cholestasis in bile duct-ligated mice. Hepatology. 2003;38:355–363. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Hinson JA, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. NADPH oxidase-derived oxidant stress is critical for neutrophil cytotoxicity during endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G243–G252. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00287.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral JS, Knight TR, Farhood A, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. Mode of cell death after acetaminophen overdose in mice: apoptosis or oncotic necrosis? Toxicol Sci. 2002;67:322–328. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/67.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajovsky H, et al. Metabolism and toxicity of thioacetamide and thioacetamide S-oxide in rat hepatocytes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:1955–1963. doi: 10.1021/tx3002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerich L, Heymann F, Tacke F. Role of IL-17 and Th17 cells in liver diseases. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:345803. doi: 10.1155/2011/345803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa N, Shinohara M, Saberi B, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N. Role of JNK translocation to mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitochondria bioenergetics in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13565–13577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708916200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbrecht BG, Billiar TR, Curran RD, Stadler J, Simmons RL. Hepatocyte injury by activated neutrophils in vitro is mediated by proteases. Ann Surg. 1993;218:120–128. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrill AH, Ross PK, Gatti DM, Threadgill DW, Rusyn I. Population-based discovery of toxicogenomics biomarkers for hepatotoxicity using a laboratory strain diversity panel. Toxicol Sci. 2009;110:235–243. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AJ, Dial SL, Casciano DA. Comparison of basal gene expression profiles and effects of hepatocarcinogens on gene expression in cultured primary human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells. Mutat Res. 2004;549:79–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann F, Hamesch K, Weiskirchen R, Tacke F. The concanavalin A model of acute hepatitis in mice. Lab Anim. 2015;49:12–20. doi: 10.1177/0023677215572841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson JA, Pike SL, Pumford NR, Mayeux PR. Nitrotyrosine-protein adducts in hepatic centrilobular areas following toxic doses of acetaminophen in mice. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:604–607. doi: 10.1021/tx9800349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JS, Buchweitz JP, Roth RA, Ganey PE. Identification of factors from rat neutrophils responsible for cytotoxicity to isolated hepatocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;59:716–724. doi: 10.1002/jlb.59.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann KJ, Streeter AJ, Axworthy DB, Baillie TA. Identification of the major covalent adduct formed in vitro and in vivo between acetaminophen and mouse liver proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;27:566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler N, et al. Two adjacent trimeric Fas ligands are required for Fas signaling and formation of a death-inducing signaling complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1428–1440. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1428-1440.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MP, Cheng L, Ju C. Identification and characterization of infiltrating macrophages in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1410–1421. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0308173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CS, Postovit LM, Lajoie GA. Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics. 2010;10:1886–1890. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichai P, Samuel D. Epidemiology of liver failure. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Abril ER, Bethea NW, McCuskey MK, Cover C, Jaeschke H, McCuskey RS. Mechanisms and pathophysiological implications of sinusoidal endothelial cell gap formation following treatment with galactosamine/endotoxin in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G211–G218. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00312.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N, et al. The polypeptide encoded by the cDNA for human cell surface antigen Fas can mediate apoptosis. Cell. 1991;66:233–243. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H. Glutathione disulfide formation and oxidant stress during acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice in vivo: the protective effect of allopurinol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;255:935–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H. Mechanisms of Liver Injury. II. Mechanisms of neutrophil-induced liver cell injury during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion and other acute inflammatory conditions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1083–G1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00568.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Cover C, Bajt ML. Role of caspases in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Life Sci. 2006;78:1670–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Farhood A, Smith CW. Neutrophils contribute to ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat liver in vivo . FASEB J. 1990;4:3355–3359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Fisher MA, Lawson JA, Simmons CA, Farhood A, Jones DA. Activation of caspase 3 (CPP32)-like proteases is essential for TNF-alpha-induced hepatic parenchymal cell apoptosis and neutrophil-mediated necrosis in a murine endotoxin shock model. J Immunol. 1998;160:3480–3486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Gujral JS, Bajt ML. Apoptosis and necrosis in liver disease. Liver Int. 2004;24:85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Ho YS, Fisher MA, Lawson JA, Farhood A. Glutathione peroxidase-deficient mice are more susceptible to neutrophil-mediated hepatic parenchymal cell injury during endotoxemia: importance of an intracellular oxidant stress. Hepatology. 1999;29:443–450. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, McGill MR, Ramachandran A. Oxidant stress, mitochondria, and cell death mechanisms in drug-induced liver injury: lessons learned from acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Drug Metab Rev. 2012a;44:88–106. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.602688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, McGill MR, Williams CD, Ramachandran A. Current issues with acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: a clinically relevant model to test the efficacy of natural products. Life Sci. 2011;88:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke H, Williams CD, Ramachandran A, Bajt ML. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and repair: the role of sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Liver Int. 2012b;32:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga B, Hong F, Kim WH, Gao B. IFN-gamma/STAT1 acts as a proinflammatory signal in T cell-mediated hepatitis via induction of multiple chemokines and adhesion molecules: a critical role of IRF-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1044–G1052. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemnitz K, Veres Z, Monostory K, Kobori L, Vereczkey L. Interspecies differences in acetaminophen sensitivity of human, rat, and mouse primary hepatocytes. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:961–967. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Sun R, Zhou R, Wei H, Tian Z. TLR-9 activation aggravates concanavalin A-induced hepatitis via promoting accumulation and activation of liver CD4+ NKT cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3768–3774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, et al. Hepato-protective effects of six schisandra lignans on acetaminophen-induced liver injury are partially associated with the inhibition of CYP-mediated bioactivation. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;231:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. II. Role of covalent binding in vivo . J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;187:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanebratt KP, Andersson TB. Evaluation of HepaRG cells as an in vitro model for human drug metabolism studies. Drug Metabol Dispos. 2008a;36:1444–1452. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.020016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanebratt KP, Andersson TB. HepaRG cells as an in vitro model for evaluation of cytochrome p450 induction in humans. Drug Metabol Dispos. 2008b;36:137–145. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.017418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass GE, Macanas-Pirard P, Lee PC, Hinton RH. The role of apoptosis in acetaminophen-induced injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:557–559. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya J, Sudo R, Mitaka T, Ikeda M, Tanishita K. Hepatic stellate cell-mediated three-dimensional hepatocyte and endothelial cell triculture model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:361–370. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Lasher CD, Milford LM, Murali TM, Rajagopalan P. A comparative study of genome-wide transcriptional profiles of primary hepatocytes in collagen sandwich and monolayer cultures. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:1449–1460. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Rajagopalan P. 3D hepatic cultures simultaneously maintain primary hepatocyte and liver sinusoidal endothelial cell phenotypes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen CD, Reisman SA. Nrf2 the rescue: effects of the antioxidative/electrophilic response on the liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;244:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight TR, Ho YS, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Peroxynitrite is a critical mediator of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in murine livers: protection by glutathione. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:468–475. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knolle PA, et al. Role of sinusoidal endothelial cells of the liver in concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury in mice. Hepatology. 1996;24:824–829. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, et al. Role of apoptosis in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22 Suppl. 2007;1:S49–S52. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon K, Kim JS, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2004;40:1170–1179. doi: 10.1002/hep.20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera O, et al. Protective effect of S-adenosylmethionine against galactosamine-induced injury of rat hepatocytes in primary culture. Physiol Res. 2006a;55:551–560. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera O, Lotková H, Kand’ár R, Hézová R, Muzáková V, Cervinková Z. The model of D-galactosamine-induced injury of rat hepatocytes in primary culture. Acta Medica. 2006b;49:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künstle G, Hentze H, Germann PG, Tiegs G, Meergans T, Wendel A. Concanavalin A hepatotoxicity in mice: tumor necrosis factor-mediated organ failure independent of caspase-3-like protease activation. Hepatology. 1999;30:1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künstle G, Leist M, Uhlig S, Revesz L, Feifel R, MacKenzie A, Wendel A. ICE-protease inhibitors block murine liver injury and apoptosis caused by CD95 or by TNF-alpha. Immunol Lett. 1997;55:5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(96)02642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küsters S, Gantner F, Künstle G, Tiegs G. Interferon gamma plays a critical role in T cell-dependent liver injury in mice initiated by concanavalin A. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:462–471. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacronique V, et al. Bcl-2 protects from lethal hepatic apoptosis induced by an anti-Fas antibody in mice. Nat Med. 1996;2:80–86. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Burns AR, Farhood A, Lynn Bajt M, Collins RG, Smith CW, Jaeschke H. Pathophysiologic importance of E- and L-selectin for neutrophil-induced liver injury during endotoxemia in mice. Hepatology. 2000a;32:990–998. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Farhood A, Hopper RD, Bajt ML, Jaeschke H. The hepatic inflammatory response after acetaminophen overdose: role of neutrophils. Toxicol Sci. 2000b;54:509–516. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/54.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Fisher MA, Simmons CA, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Parenchymal cell apoptosis as a signal for sinusoidal sequestration and transendothelial migration of neutrophils in murine models of endotoxin and Fas-antibody-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 1998;28:761–767. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCluyse EL, Alexandre E. Isolation and culture of primary hepatocytes from resected human liver tissue. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;640:57–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-688-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCluyse EL, Alexandre E, Hamilton GA, Viollon-Abadie C, Coon DJ, Jolley S, Richert L. Isolation and culture of primary human hepatocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;290:207–229. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-838-2:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Buters JT, Pineau T, Fernandez-Salguero P, Gonzalez FJ. Role of CYP2E1 in the hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12063–12067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WM. Etiologies of acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:142–152. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legembre P, Beneteau M, Daburon S, Moreau JF, Taupin JL. Cutting edge: SDS-stable Fas microaggregates: an early event of Fas activation occurring with agonistic anti-Fas antibody but not with Fas ligand. J Immunol. 2003;171:5659–5662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XY, Zhong M, Feng LF, Zhu BY, Tang SS, Liao DF. siRNA-mediated Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl gene silencing sensitizes human hepatoblastoma cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:450–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leist M, Gantner F, Jilg S, Wendel A. Activation of the 55 kDa TNF receptor is necessary and sufficient for TNF-induced liver failure, hepatocyte apoptosis, and nitrite release. J Immunol. 1995;154:1307–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Zhu H, Xu CJ, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]