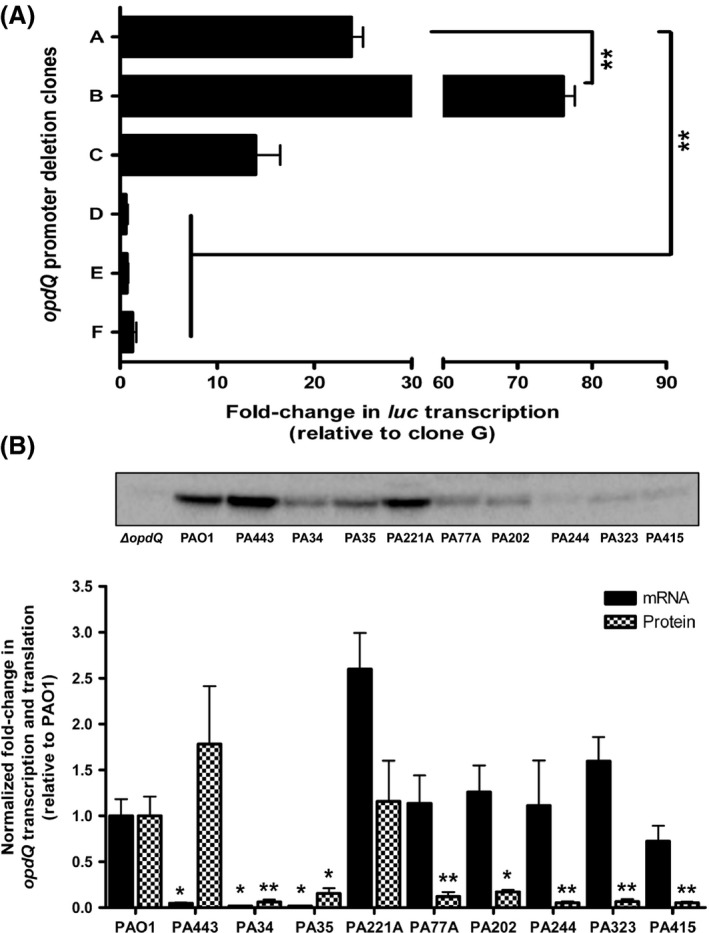

Figure 2.

Promoter activity, transcription, and translation of OpdQ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and clinical strains grown in ambient oxygen. (A) Relative luciferase expression of opdQ::promoter fusion clones. Luciferase transcription was relative to clone G, normalized to rpoD transcription, and determined by qPCR. Clone A represents sequences of the entire PA3037‐opdQ intergenic region, clone B represents the removal of sequences upstream of the ‐35 element, clone C represents an internal deletion of the L1 loop within the opdQ UTR, clone D represents an internal deletion/disruption of the L2 loop which included the ‐35 element, clone E represents removal of the ‐35 element, and clone F represents the removal of both ‐35 and ‐10 elements. Clone G contained only the Shine–Dalgarno sequence and served as the control/comparator. Experiments were performed with at least three independent biological cultures. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Significantly different from full‐length opdQ promoter (clone A); **P < 0.01. (B) Transcript and protein levels of OpdQ relative to wild‐type strain PAO1. Transcription of opdQ in the clinical strains was compared to PAO1, normalized to rpoD transcription, and determined by qPCR. The amount of OpdQ protein was determined by immunoblot for PAO1, an opdQ knockout mutant (ΔopdQ), and clinical strains of P. aeruginosa using 15 μg of whole cell lysate. Alternatively, 30 μg of protein was used for strains PA34, PA35, PA77A, PA202, PA244, PA323, and PA415 that produced very low levels of OpdQ. OpdQ production was normalized to total protein by measuring Stain‐Free fluorescence on the LF polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Three independent experiments were performed. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Significantly different fold‐changes transcription and translation of OpdQ from PAO1; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.