Abstract

Noncardiac chest pain (NCCP) is one of the most common esophageal symptoms and lacks a clearly defined mechanism. The most common cause of NCCP is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). One of the accepted mechanisms of NCCP in a patient without GERD has been altered visceral sensitivity. Mast cells may play a role in visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. In this case, a patient with NCCP and dysphagia who was unresponsive to proton pump inhibitor treatment had an increased esophageal mast cell infiltration and responded to 14 days of antihistamine and antileukotriene treatment. We suggest that there may be a relationship between esophageal symptoms such as NCCP and esophageal mast cell infiltration.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux, Mast cell, Noncardiac chest pain

INTRODUCTION

Noncardiac chest pain (NCCP) is defined by recurrent episodes of substernal chest pain without a cardiac cause.1 Identified esophageal causes of NCCP include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophageal dysmotility, and visceral hypersensitivity.2 For GERD-related NCCP, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the main treatment option. However, for non-GERD-related NCCP, there is no clearly accepted mechanism or treatment strategy. One possible mechanism of pain in patients with non-GERD-related NCCP is an increased nociceptive response and a decreased nociceptive threshold.3 Mucosal mast cells are important regulators of intestinal sensory and motor function. Tryptase and histamine are released after degranulation from mast cells and activate enteric nerves, resulting in neuronal hyperexcitability.4 Mast cells can also be associated with the pathophysiology of symptoms in some gastrointestinal disorders, such as celiac sprue, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonulcer dyspepsia.5 In a case-control study, an increased number of mucosal mast cells was demonstrated in colonic or duodenal biopsy specimens from patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).6 Furthermore, symptoms in 67% of these patients improved with the administration of H1 and H2 receptor antagonists, with or without the concurrent administration of mast cell mediator release inhibitors.6 However, there have been few studies describing an association between esophageal mucosal mast cell infiltration and esophageal symptoms.7 Herein, we describe our experience with a 32-year-old woman who had NCCP that did not respond to PPI treatment. This patient had an increased number of mast cells in the esophageal mucosa, and her symptoms were successfully controlled with H1 and H2 receptor antagonists and antileukotrienes.

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old woman visited Samsung Medical Center (Seoul, Korea) with an 8-month history of recurrent retrosternal chest pain. She described a burning sensation that was not related to meals. Additionally, she often complained of regurgitation when in the supine position and intermittent dysphagia to both solids and liquids. She had allergic rhinitis, but her symptoms were not associated with particular foods. She had been treated for 4 months with once-daily esomeprazole (40 mg) and prokinetics (Motilitone® 30 mg three times a day), without any improvement in her symptoms.

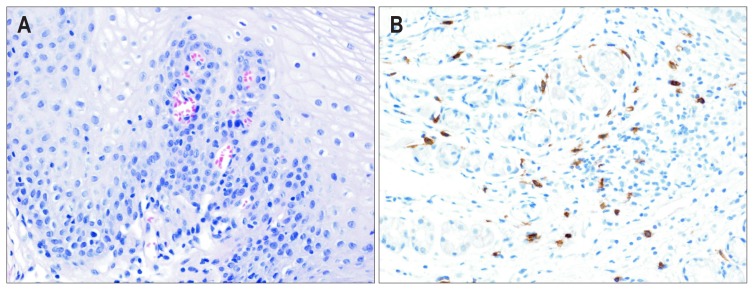

She underwent a thorough workup, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), esophagography, high-resolution esophageal manometry, 24-hour esophageal impedance-pH monitoring, and computed tomography (CT) of the chest. There were no specific findings on the EGD (Fig. 1). During EGD, we performed random biopsies of the upper, middle, and lower esophagus to evaluate for eosinophilic or mast cell infiltration. Mast cells in the epithelium and lamina propria were counted using CD117 immunostaining. The number of mast cells is presented as the largest cell number per high-power field (HPF, ×400). Esophagography demonstrated suspicious mild luminal irregularity at the distal esophagus. High-resolution esophageal manometry revealed normal peristalsis of the esophageal body and normal lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. The percentage of total pH <4 time was 1.1%, according to 24-hour esophageal impedance-pH monitoring. There were no specific findings on the chest CT. An esophageal biopsy showed an increased mucosal mast cell count of up to 66/HPF, without evidence of eosinophilic infiltration. Biopsies of the stomach and duodenum showed a mucosal mast cell count of up to 16/HPF and up to 40/HPF, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Microscopic findings. (A) A few mast cells without any eosinophils, as visualized by H&E staining (×200); and (B) increased mast cell infiltration as visualized by immunohistochemical staining for CD117 in the esophageal mucosa.

The patient underwent allergic tests. The total serum IgE level was 30.2 U/mL, and the serum eosinophil count was 50/L. House dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae) and Mugwort exhibited 3+ positivity on skin prick testing. Based on these test results, we assumed that she had symptomatic allergic mastocytic esophagitis and treated her with an H1 receptor antagonist (Chlorpheniramine®), an H2 receptor antagonist (Ranitidine®), and an antileukotriene agent (Monteleukast®) for 14 days. After treatment, her symptoms improved by more than 50%. She did not have any chest pain after continuing the medication for another month. Eight months after her symptoms had resolved, she returned to our clinic with recurrent retrosternal chest pain. We prescribed the same medication for 1 month, after which her symptoms were again relieved.

DISCUSSION

Mucosal mast cells play an important role in visceral hypersensitivity in patients with IBS, who have increased mast cell infiltration in the mucosa of the intestinal tract.8,9 In a retrospective study, Jakate et al.6 proposed the term mastocytic enterocolitis to describe the presence of an increased number of gastrointestinal (GI) mucosal mast cells upon colonic or duodenal biopsy in patients with chronic intractable diarrhea. Patients with mastocytic enterocolitis who were treated with antihistamines and/or cromolyn sodium showed a significant reduction in diarrhea.6 In a recent retrospective study, Akhavein et al.10 described patients with the following characteristics: (1) symptoms of GI dysmotility; (2) increased mast cells in the GI tract mucosa; (3) a history of food or environmental allergies; (4) nocturnal awakening; and (5) elevated histamine levels. This study suggested the use of a new term, allergic mastocytic gastroenteritis, for a new type of GI mast cell disorder. As mucosal mast cells are distributed throughout the GI tract, and their relation with visceral hypersensitivity has been reported in previous studies, we can assume that increased esophageal mast infiltration may also influence esophageal hypersensitivity. Recently, Lee et al.7 reported a higher mucosal mast cell count in NCCP patients with hypersensitivity of the esophagus and functional chest pain than in controls. These authors also showed that mucosal mast cell infiltration was associated with smooth muscle segmental changes during esophageal contraction.11 Given this background, we report a case of non-GERD-related NCCP; the patient had increased esophageal mast cell infiltration, and her symptoms were successfully controlled with antihistamines and antileukotrienes.

NCCP is a common disease with a global prevalence of 13%; it is very costly and has a significant effect on health care systems.12,13 NCCP can be divided into GERD-related NCCP and non-GERD-related NCCP. Non-GERD-related NCCP can be demonstrated in up to 58% of patients with NCCP.14 For non-GERD-related NCCP cases, esophageal motility disorder, visceral hypersensitivity, altered autonomic activity, and psychological disorders have been suggested as the underlying mechanisms.2 However, patients with non-GERD-related NCCP frequently do not receive a definitive diagnosis, even after a workup, which makes it difficult to determine the treatment strategy clinically. In this case, we showed that symptoms in a patient with esophageal mast cell infiltration were successfully relieved with antihistamines and an antileukotriene agent, suggesting that visceral hypersensitivity induced by mast cell infiltration is a treatable cause of non-GERD-related NCCP. However, further large-scale prospective studies are required to better understand the relationship between esophageal symptoms and mast cell infiltration affecting visceral sensitivity.

In this case, we used chlorpheniramine (an H1 receptor antagonist) to prevent symptoms because histamine is the main mast cell mediator, and of its four receptor subtypes, H1 is the main target for visceral pain.15,16 Recently, the transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) family has been identified as a common pathway for several mediators of visceral hypersensitivity, including histamine, tryptase, and serotonin.17,18 Chlorpheniramine also is a TRPV receptor antagonist.19 Therefore, chlorpheniramine might work in this case by antagonizing the H1 receptor and through the direct inhibition of TRPV. In addition, chlorpheniramine can be thought of as a selective serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor due to its actions on both serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons.20 Accordingly, its visceral analgesic effect may also have partially contributed to the relief of symptoms in this patient.21 Although data are limited, in previous studies by Lee et al.7 and Yu et al.,22 the esophageal mast cell count in the healthy group was 7.6 cells/HPF and 3.79 cells/HPF, respectively. This patient had a markedly increased level of esophageal mast cell infiltration (66 cells/HPF). The mucosal mast cell count was also increased in the stomach and duodenum (up to 16 cells/HPF and up to 40 cells/HPF, respectively). However, the patient did not have any corresponding enteric symptoms. In addition, considering the mast cell count that has been reported in the stomach and duodenum of healthy persons,6,23 which are relatively higher than in the esophagus, the esophagus seemed to be the main site of mast cell infiltration in the present case.

Considering the refractory burning sensation and intermittent dysphagia reported by this patient, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) should also be considered. Furthermore, esophageal mastocytosis can occur in patients with EoE.24,25 However, no typical endoscopic features of EoE were seen upon EGD. Biopsies of the upper, middle, and lower esophagus showed neither eosinophilia nor other histologic features of EoE, including microabscess formation, superficial layering, and extracellular eosinophil granules.26 In addition, the patient received PPI treatment for 4 months, but her symptoms were not improved, and pathologic acid exposure was not observed in the 24-hour esophageal impedance-pH monitoring. Thus, we could exclude EoE, PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia, and refractory GERD.26

Limitations of this case include the fact that we did not directly evaluate mast cell activation by measuring histamine or tryptase released from mast cell degranulation and did not perform a follow-up biopsy to confirm a reduction in the esophageal mast cell count after treatment. However, an association between mast cell activation and NCCP is indirectly suggested by repeated responses to treatment with antihistamines and an antileukotriene agent. Nevertheless, further studies, including an assessment of mast cell activation and the pathologic confirmation of the treatment response, are needed to draw a firm conclusion. In conclusion, we consider that non-GERD-related NCCP can be attributed to visceral hypersensitivity, which can be associated with mast cell infiltration of the esophageal mucosa. Therefore, an endoscopic esophageal mucosal biopsy to evaluate mast cell infiltration may help physicians to determine the treatment for patients with non-GERD-related NCCP, which is particularly difficult to treat.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fass R, Fennerty MB, Ofman JJ, et al. The clinical and economic value of a short course of omeprazole in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:42–49. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Handel D, Fass R. The pathophysiology of non-cardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(Suppl 3):S6–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fass R, Navarro-Rodriguez T. Noncardiac chest pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:636–646. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181684c6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Traver E, Torres R, de Mora F, Vergara P. Mucosal mast cells mediate motor response induced by chronic oral exposure to ov-albumin in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:e34–e43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miner PB., Jr The role of the mast cell in clinical gastrointestinal disease with special reference to systemic mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96(3 Suppl):40S–43S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12469015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakate S, Demeo M, John R, Tobin M, Keshavarzian A. Mastocytic enterocolitis: increased mucosal mast cells in chronic intractable diarrhea. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:362–367. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-362-MEIMMC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H, Chung H, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC. Heterogeneity of mucosal mast cell infiltration in subgroups of patients with esophageal chest pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:786–793. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Sullivan M, Clayton N, Breslin NP, et al. Increased mast cells in the irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:449–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2000.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weston AP, Biddle WL, Bhatia PS, Miner PB., Jr Terminal ileal mucosal mast cells in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1590–1595. doi: 10.1007/BF01303164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhavein MA, Patel NR, Muniyappa PK, Glover SC. Allergic mastocytic gastroenteritis and colitis: an unexplained etiology in chronic abdominal pain and gastrointestinal dysmotility. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:950582. doi: 10.1155/2012/950582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SW, Lee H, Lee HJ, et al. Esophageal mucosal mast cell infiltration and changes in segmental smooth muscle contraction in noncardiac chest pain. Dis Esophagus. 2015;28:512–519. doi: 10.1111/dote.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford AC, Suares NC, Talley NJ. Meta-analysis: the epidemiology of noncardiac chest pain in the community. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:172–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter JE, Bradley LA, Castell DO. Esophageal chest pain: current controversies in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:66–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-1-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fass R, Naliboff B, Higa L, et al. Differential effect of long-term esophageal acid exposure on mechanosensitivity and chemosensitivity in humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klooker TK, Braak B, Koopman KE, et al. The mast cell stabiliser ketotifen decreases visceral hypersensitivity and improves intestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2010;59:1213–1221. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.213108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deiteren A, De Man JG, Ruyssers NE, Moreels TG, Pelckmans PA, De Winter BY. Histamine H4 and H1 receptors contribute to postinflammatory visceral hypersensitivity. Gut. 2014;63:1873–1882. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cenac N, Altier C, Motta JP, et al. Potentiation of TRPV4 signalling by histamine and serotonin: an important mechanism for visceral hypersensitivity. Gut. 2010;59:481–488. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amadesi S, Nie J, Vergnolle N, et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 sensitizes the capsaicin receptor transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 to induce hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4300–4312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5679-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadofsky LR, Campi B, Trevisani M, Compton SJ, Morice AH. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1-mediated calcium responses are inhibited by the alkylamine antihistamines dexbrompheniramine and chlorpheniramine. Exp Lung Res. 2008;34:681–693. doi: 10.1080/01902140802339623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellbom E. Chlorpheniramine, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and over-the-counter (OTC) treatment. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:689–690. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickman R, Maradey-Romero C, Fass R. The role of pain modulators in esophageal disorders: no pain no gain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:603–610. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Y, Ding X, Wang Q, Xie L, Hu W, Chen K. Alterations of mast cells in the esophageal mucosa of the patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Gastroenterol Res. 2011;4:70–75. doi: 10.4021/gr284w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegert SI, Diebold J, Ludolph-Hauser D, Löhrs U. Are gastrointestinal mucosal mast cells increased in patients with systemic mastocytosis? Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:560–565. doi: 10.1309/2880LF7Q6XK3HA3Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Straumann A, Bauer M, Fischer B, Blaser K, Simon HU. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T(H)2-type allergic inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:954–961. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, et al. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]