Abstract

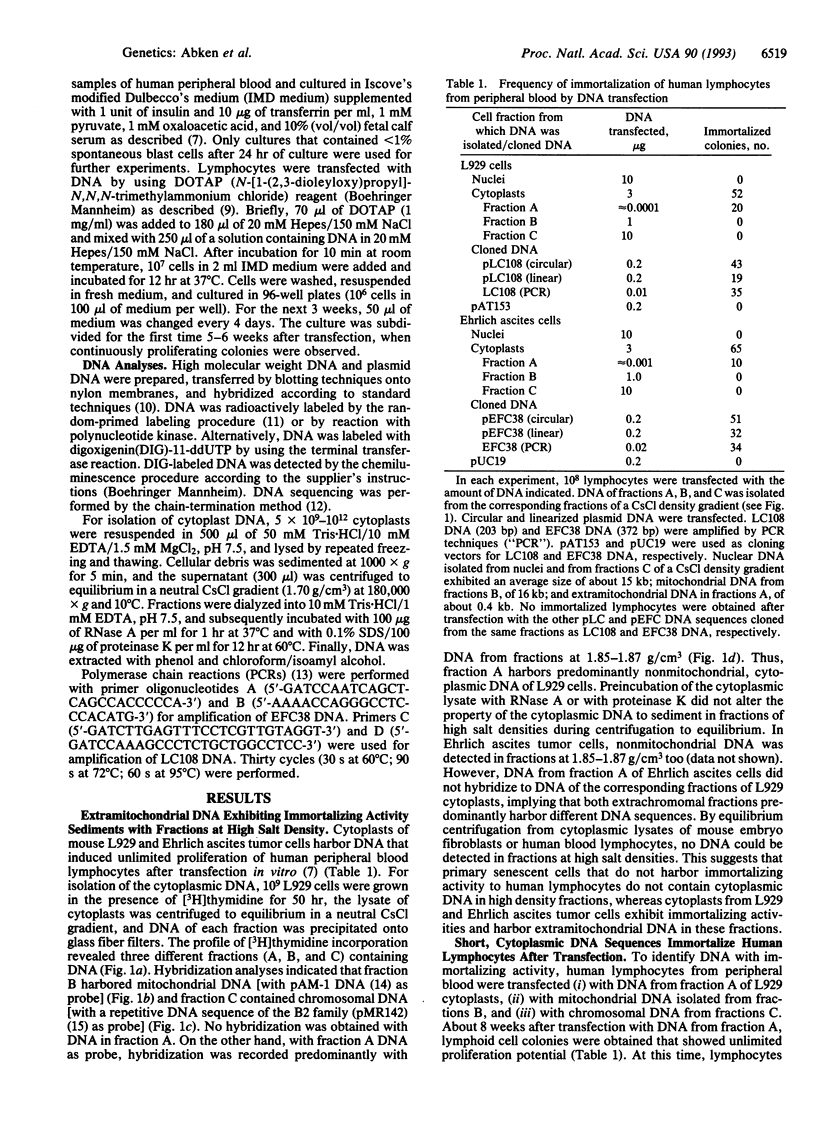

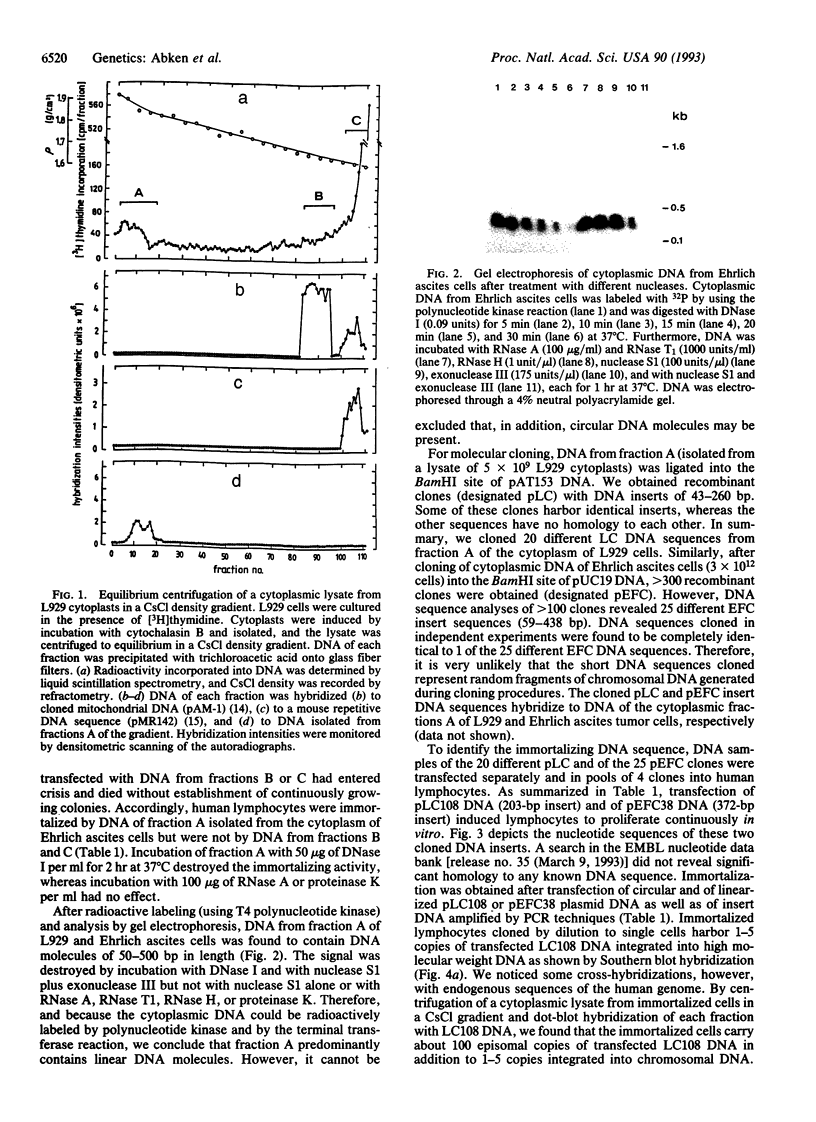

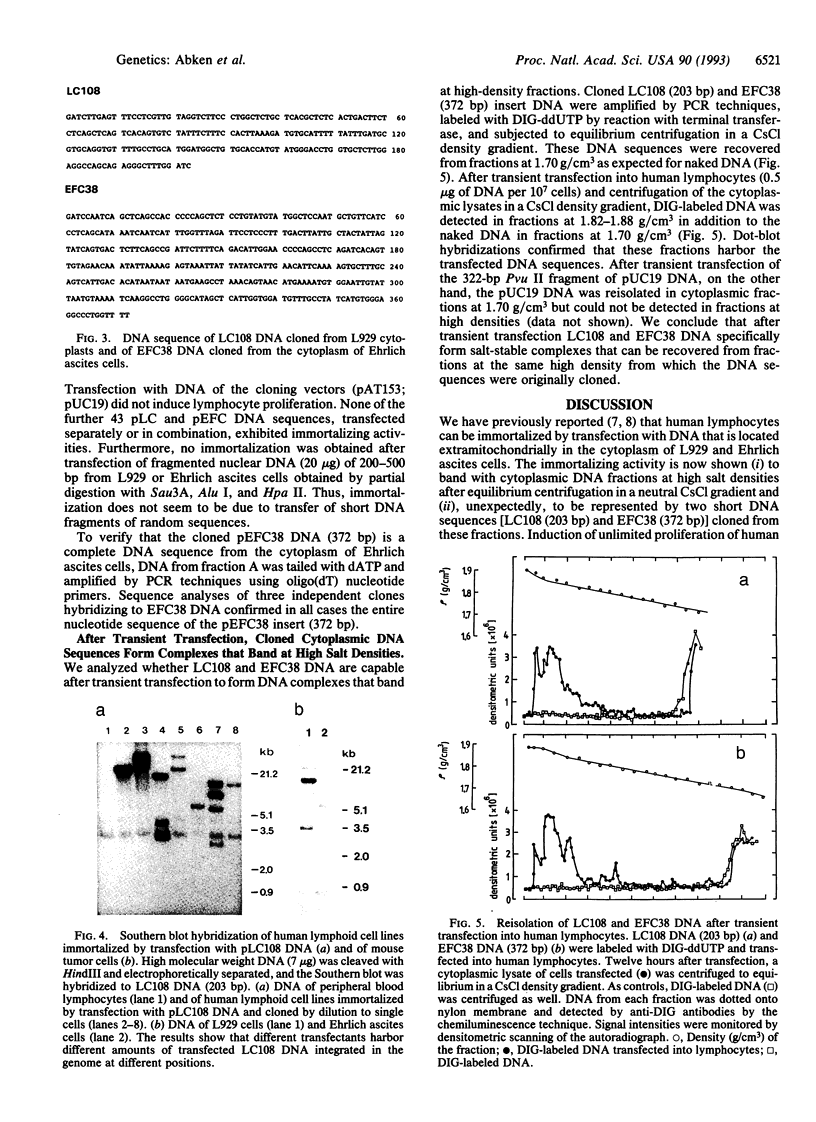

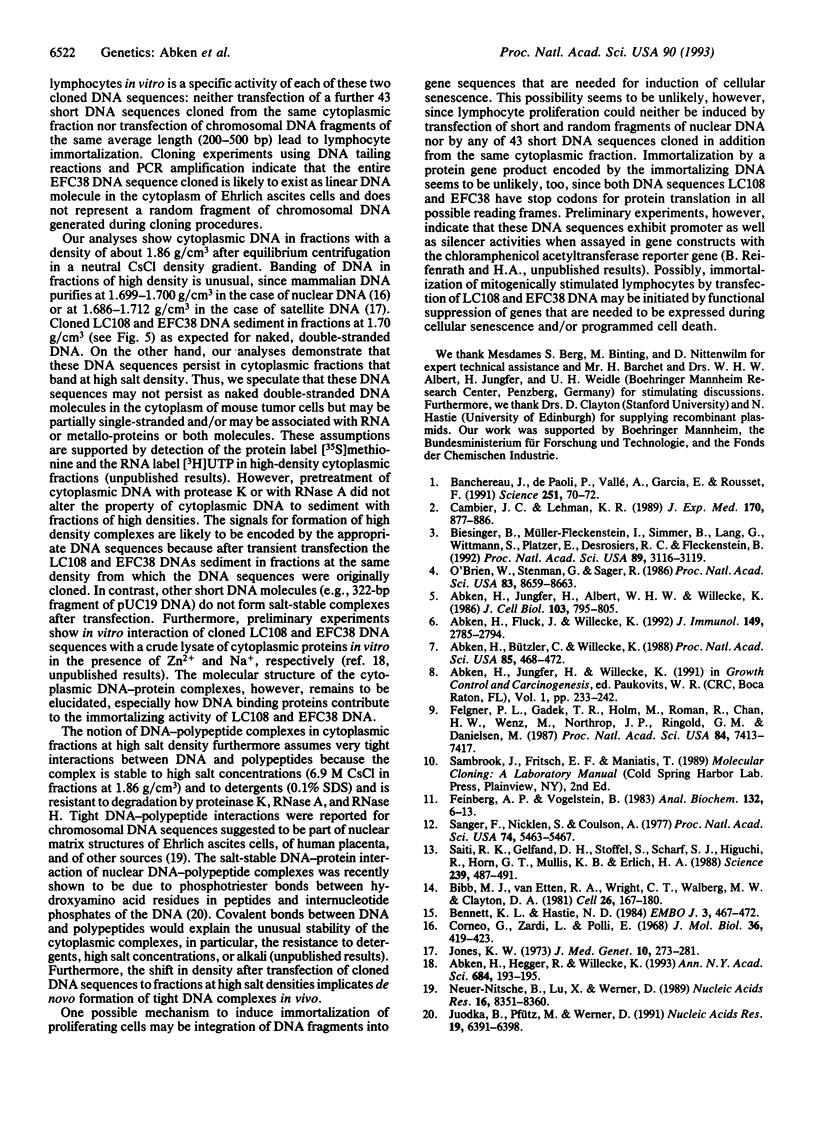

Cytoplasts of mouse L929 and Ehrlich ascites tumor cells harbor DNA sequences that induce unlimited proliferation ("immortalization") of human lymphocytes after transfection in vitro. By equilibrium centrifugation of cytoplasmic lysates in a neutral CsCl gradient, the immortalizing activity was recovered together with extramitochondrial fractions at high salt densities (1.85-1.87 g/cm3). Unexpectedly, these fractions contain linear DNA molecules of 50-500 bp in length. In contrast, cytoplasts of primary, senescent cells (mouse embryo fibroblasts, human lymphocytes) do not harbor DNA in the corresponding fractions. Cytoplasmic DNA isolated from high-density fractions of mouse tumor cells was cloned in subset libraries, and of 45 DNA sequences we identified 2 clones--one from L929 cytoplasts (203 bp) and another one from the cytoplasm of Ehrlich ascites cells (372 bp)--that induce unlimited proliferation of human lymphocytes in vitro. Immortalized lymphoid cells harbor 1-5 copies of transfected DNA integrated into chromosomal DNA, whereas about 100 copies were found as episomal DNA in the cytoplasmic fraction. No immortalization could be induced by transfection of nuclear DNA randomly fragmented to 200-500 bp. Although the cloned DNA sedimented at 1.70 g/cm3, after transient transfection into lymphocytes, these DNA sequences form salt-stable complexes that sediment in fractions at the same high density (1.82-1.88 g/cm3) from which they were originally cloned. The high-density banding of these cytoplasmic DNA sequences may be due to association with RNA and/or with (metallo-) proteins in vivo. Since both cloned DNA sequences with immortalizing activity have stop codons for protein translation in all possible reading frames, immortalization may be induced by insertional inactivation or functional suppression of genes that are needed to be expressed during cellular senescence or programmed cell death.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abken H., Bützler C., Willecke K. Immortalization of human lymphocytes by transfection with DNA from mouse L929 cytoplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jan;85(2):468–472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abken H., Fluck J., Willecke K. Four cell-secreted cytokines act synergistically to maintain long term proliferation of human B cell lines in vitro. J Immunol. 1992 Oct 15;149(8):2785–2794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abken H., Hegger R., Willecke K. A DNA-binding zinc-protein increases the immortalizing activity of an extrachromosomal DNA sequence from mouse L929 cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993 Jun 11;684:193–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb32281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abken H., Jungfer H., Albert W. H., Willecke K. Immortalization of human lymphocytes by fusion with cytoplasts of transformed mouse L cells. J Cell Biol. 1986 Sep;103(3):795–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J., de Paoli P., Vallé A., Garcia E., Rousset F. Long-term human B cell lines dependent on interleukin-4 and antibody to CD40. Science. 1991 Jan 4;251(4989):70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1702555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K. L., Hastie N. D. Looking for relationships between the most repeated dispersed DNA sequences in the mouse: small R elements are found associated consistently with long MIF repeats. EMBO J. 1984 Feb;3(2):467–472. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01829.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb M. J., Van Etten R. A., Wright C. T., Walberg M. W., Clayton D. A. Sequence and gene organization of mouse mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 1981 Oct;26(2 Pt 2):167–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesinger B., Müller-Fleckenstein I., Simmer B., Lang G., Wittmann S., Platzer E., Desrosiers R. C., Fleckenstein B. Stable growth transformation of human T lymphocytes by herpesvirus saimiri. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Apr 1;89(7):3116–3119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier J. C., Lehmann K. R. Ia-mediated signal transduction leads to proliferation of primed B lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989 Sep 1;170(3):877–886. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneo G., Zardi L., Polli E. Human mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Biol. 1968 Sep 28;36(3):419–423. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. P., Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983 Jul 1;132(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felgner P. L., Gadek T. R., Holm M., Roman R., Chan H. W., Wenz M., Northrop J. P., Ringold G. M., Danielsen M. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Nov;84(21):7413–7417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. W. Satellite DNA. J Med Genet. 1973 Sep;10(3):273–281. doi: 10.1136/jmg.10.3.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juodka B., Pfütz M., Werner D. Chemical and enzymatic analysis of covalent bonds between peptides and chromosomal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991 Dec 11;19(23):6391–6398. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.23.6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuer-Nitsche B., Lu X. N., Werner D. Functional role of a highly repetitive DNA sequence in anchorage of the mouse genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988 Sep 12;16(17):8351–8360. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.17.8351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien W., Stenman G., Sager R. Suppression of tumor growth by senescence in virally transformed human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Nov;83(22):8659–8663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki R. K., Gelfand D. H., Stoffel S., Scharf S. J., Higuchi R., Horn G. T., Mullis K. B., Erlich H. A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988 Jan 29;239(4839):487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]