Abstract

The coordination chemistry of metal nitrosyls has expanded rapidly in the past decades due to major advances of nitric oxide and its metal compounds in biology. This review article highlights advances made in the area of multinuclear metal nitrosyl complexes, including Roussin’s salts and their ester derivatives from 2003 to present. The review article focuses on isolated multinuclear metal nitrosyl complexes and is organized into different sections by the number of metal centers and bridging ligands.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, metal nitrosyl, multinuclear metal nitrosyl, nitrosyl, dinuclear metal nitrosyl, trinuclear metal nitrosyl, tetranuclear metal nitrosyl, pentanuclear metal nitrosyl, hexanuclear metal nitrosyl, octanuclear metal nitrosyl, Roussin’s red salt, Roussin’s red salt ester, Roussin’s black salt, dinitrosyl iron complex, iron sulfur cluster, metal nitrosyl cluster

1. Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous lipophilic radical molecule that plays important roles in several physiological and pathophysiological processes in mammals, including activating the immune response, serving as a neurotransmitter, regulating the cardiovascular system, and acting as an endothelium-derived relaxing factor [1–3]. NO functions in eukaryotes both as a signal molecule at nanomolar concentrations and as a cytotoxic agent at micromolar concentrations [4]. The latter arises from the ability of NO to react readily with a variety of cellular targets leading to thiol S-nitrosation [5], amino acid N-nitrosation [6], and nitrosative DNA damage [7–8].

Nitric oxide can readily bind to metals to give metal-nitrosyl (M-NO) complexes [9]. Some of these species are known to play roles in biological NO storage and transport [10–28]. The coordination chemistry of metal nitrosyls has expanded rapidly in the past decades. These complexes have different biological, photochemical, or spectroscopic properties due to distinctive structural features, and are often studied by using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), infrared (IR) vibrational frequencies (νNO), X-ray crystallography, Mössbauer, theoretical calculations, etc [29–34].

The aim of this review is to highlight advances made in the area of multinuclear metal nitrosyl complexes, including Roussin’s salts and their ester derivatives. It summarizes the literature from 2003 to present. There have been several excellent reviews covering different aspects of metal nitrosyl chemistry in recent years [35–42], and we have tried to avoid direct overlap with the subject matter of those articles. This review is focused on recent advances on the synthesis and characterizations of isolated multinuclear metal nitrosyl complexes with structural certainty rather than in situ identifications. It is organized by the number of metal centers and further arranged into different sections based on the type of bridging ligands.

2. Dinuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

2.1. Homodinuclear Cluster Linked by Sulfur – RRS and RRE Types

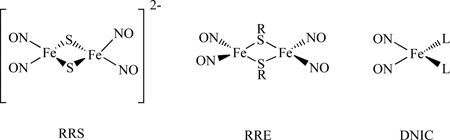

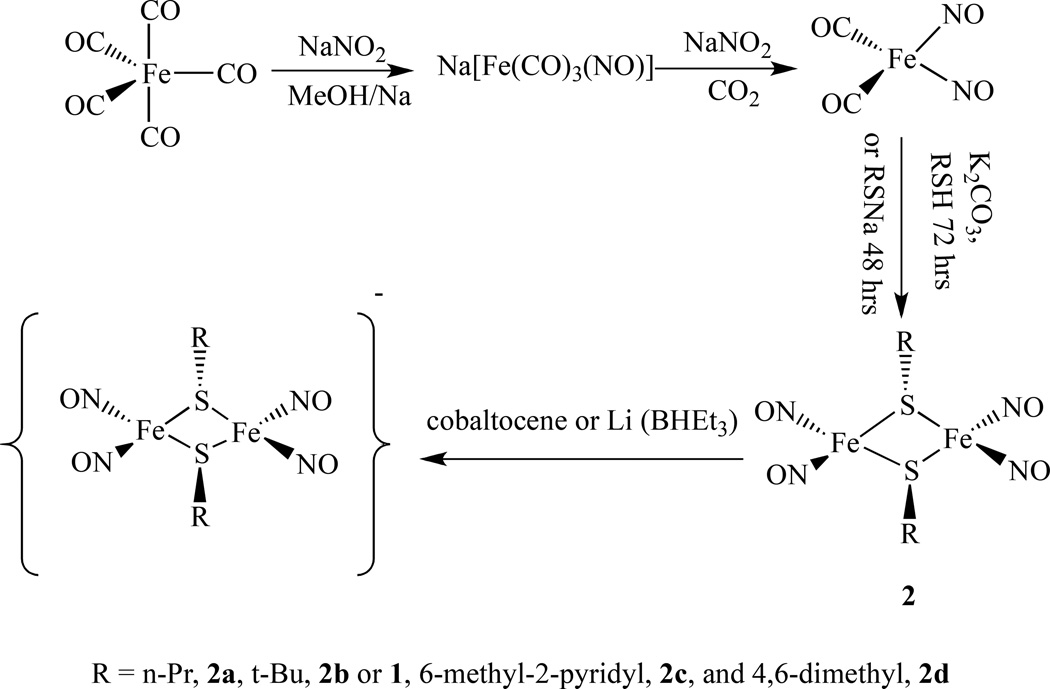

Roussin’s Red Salt [Fe2(µ-S)2(NO)4]2− , (RRS), and Roussin’s Red Salt Ester, [Fe2(µ-SR)2(NO)4], (RRE), have been known since the mid-nineteenth century [43–44]. They can be considered as the dinuclear form of a dinitrosyl iron complex, (DNIC) [35–46]. The structures of RRS, RRE and DNIC are shown below. RRS and RRE can be generated in situ by directly reacting nitric oxide with proteins containing [Fe–S] clusters, such as rubredoxin and ferredoxin [47]. They were discovered as being bound to the cysteine residues of proteins within body tissues [48]. In addition, the reactions of NO with [4Fe-4S] clusters of Wbl proteins and a Rieske-type protein form RRE [49]. Using synthetic model compounds of [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S], the RRE species were also identified from these reactions [50–51].

RRE and RRS molecules have been tested for their effects on tumor cell growth and are efficient NO donors that lead to eventual cell death [52–53]. The bactericidal effect on the food-spoilage bacterium Clostridium sporogenes is effective in the millimolar range [54]. Some water-soluble RREs act as much slower yet higher stoichiometric NO-release agents with low cytotoxicity towards immortalized vascular endothelial cells [55–56]. Because of many recent discoveries of the biological activities of RRS and RRE, there is a renewed interest in preparing new types of RRS and RRE and investigating their properties.

2.1.1. Preparation and Spectroscopic Properties of RRS and RRE

RREs may be synthesized through the alkylation of Roussin’s Red Salt (RRS) with an alkyl halide or treatment of Fe2(µ-I)2(NO)4 with an organic thiol compound in the presence of a proton acceptor as shown in Scheme 1[57].

Scheme 1.

Generalized synthetic pathway for the conversion of RRS to RRE.

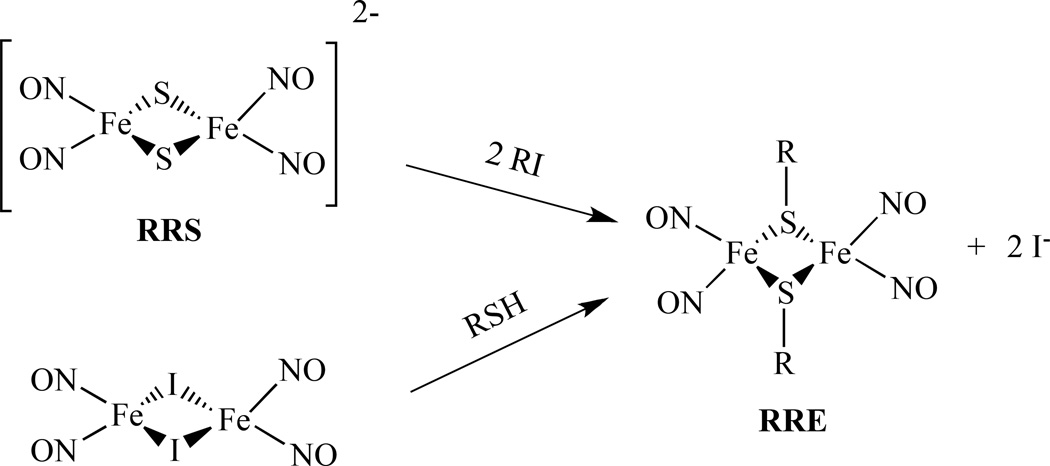

Lippard et al. reported another way to synthesize RRE. An RRE with t-Bu, [Fe(StBu)(NO)2]2, 1, was obtained from the reaction of excess NO with (Et4N)[Fe(StBu)3(NO)]. The latter was generated in situ by treating (Et4N)2[Fe(StBu)4] with 1 mol-equiv of NO (g) at low temperature (Scheme 2) [58].

Scheme 2.

Synthetic scheme for the RRE from (Et4N)[Fe(StBu)3(NO)] and NO [58].

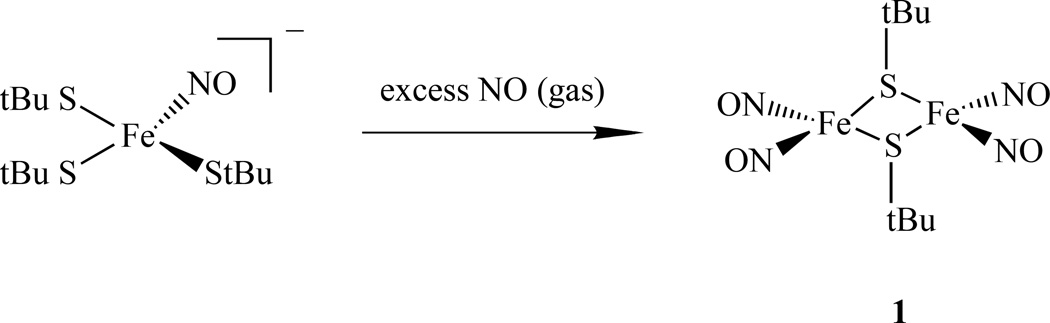

Recently we reported two different ways of preparing a series of Roussin's Red Salt Esters [Fe2(µ-SR)2(NO)4], 2, (R = n-Pr, 2a, t-Bu, 2b or 1, 6-methyl-2-pyridyl, 2c, and 4,6-dimethyl-2-pyrimidyl, 2d). One method is to mix freshly prepared Fe(NO)2(CO)2 with equal molar amounts of the corresponding thiol ligands in the presence of potassium carbonate at room temperature for 72 h; and another way is to treat Fe(NO)2(CO)2 with equal molar of thiolate ligands at room temperature for 48 h (Scheme 3) [59].

Scheme 3.

Synthetic scheme for the formation of RRE from Fe(CO)5 and NaNO2 [59].

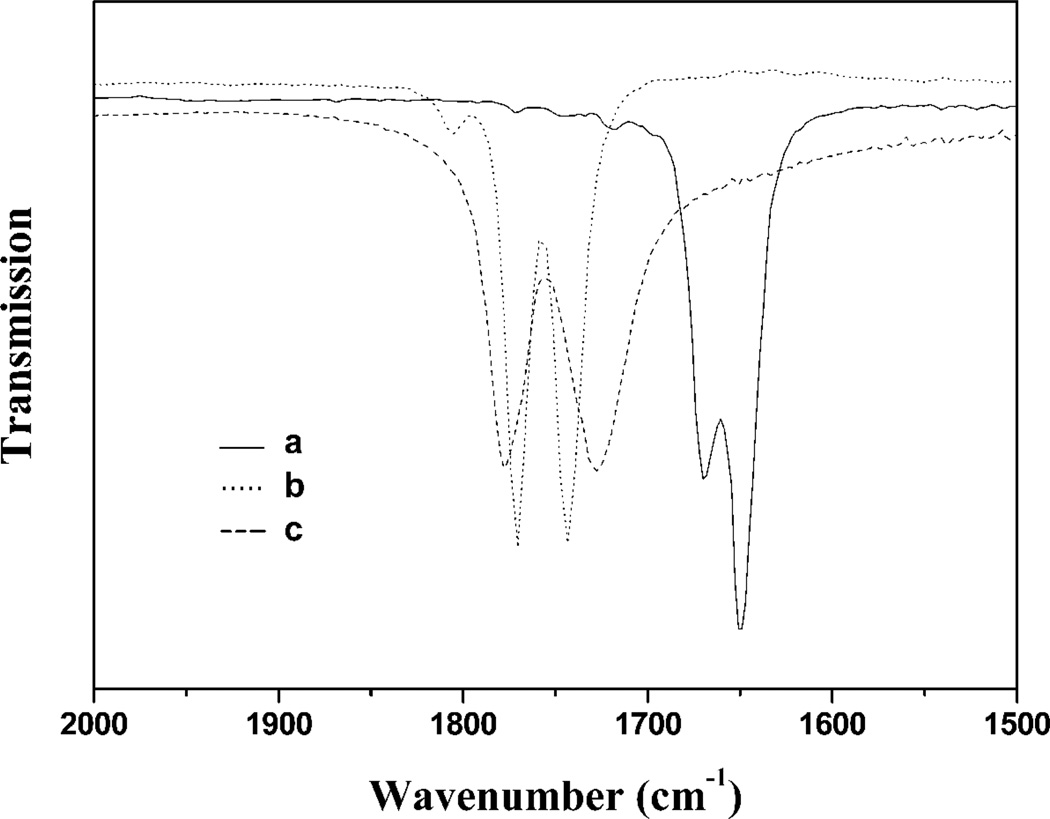

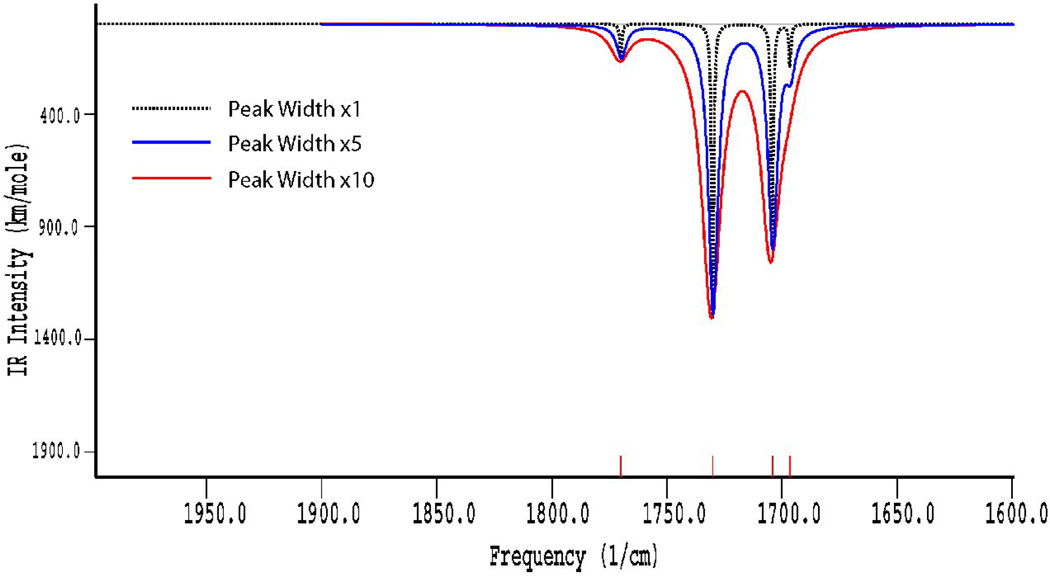

The infrared spectra of these compounds were studied in detail in both KBr pellets and in THF solution. The typical IR absorptions of nitroysl groups (νNO) shifted from 1807, 1760 cm−1 to 1805–1823, 1770–1793 and 1743–1759 cm−1, due to these sulfur-containing ligands only acting as weak electron donors. These RREs displayed one weak and two strong NO stretching frequencies in solution, but only two strong NO stretching frequencies in solid, attributed to the trans-isomer in solid state and the co-existence of cis- and trans- isomers in solution (Figure 1). The vibrational modes of the cis- and trans-isomers were further confirmed by the frequency calculations using Density Functional Theory (DFT). The calculated results for the cis- isomer showed four different vibrational modes, whereas the trans- isomer resulted in only two vibrational modes. The IR spectra of the cis- isomer simulated with Amsterdam Density Functional (ADF) software and plotted using different peak widths (Figure 2) indicated that the peak width and intensity overlap of the cis- and trans- isomers make the vibrational band at 1704 cm−1 unresolved. Hence, these complexes actually showed only three vibrational bands for the NO moieties in the experimental solution IR spectra.

Figure 1.

Experimental infrared spectra of RRE complexes in the nitrosyl stretching region: (a) 2b− recorded in tetrahydrofuran, (b) 2b recorded in tetrahydrofuran (mixture of the cis- and trans- isomers), and (c) 2c recorded in KBr (only trans-isomers) [59].

Figure 2.

The calculated vibrational spectra using different peak widths for the cis- isomer of the RRE complex 2a [59].

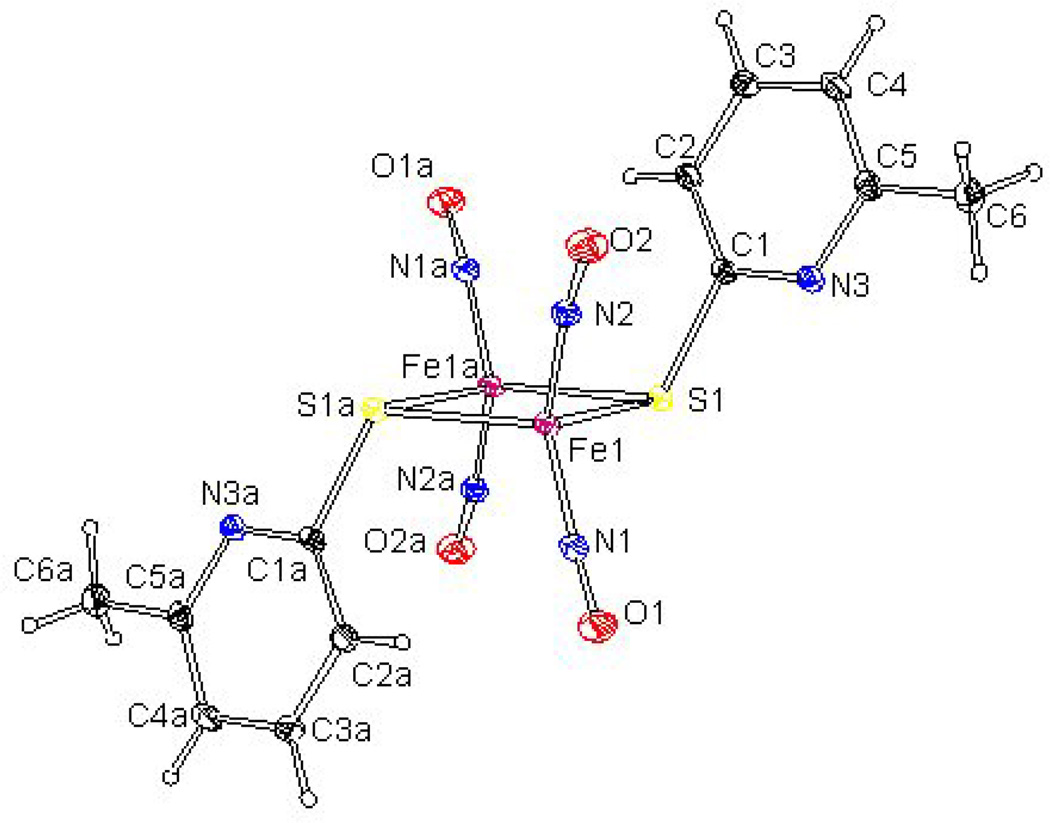

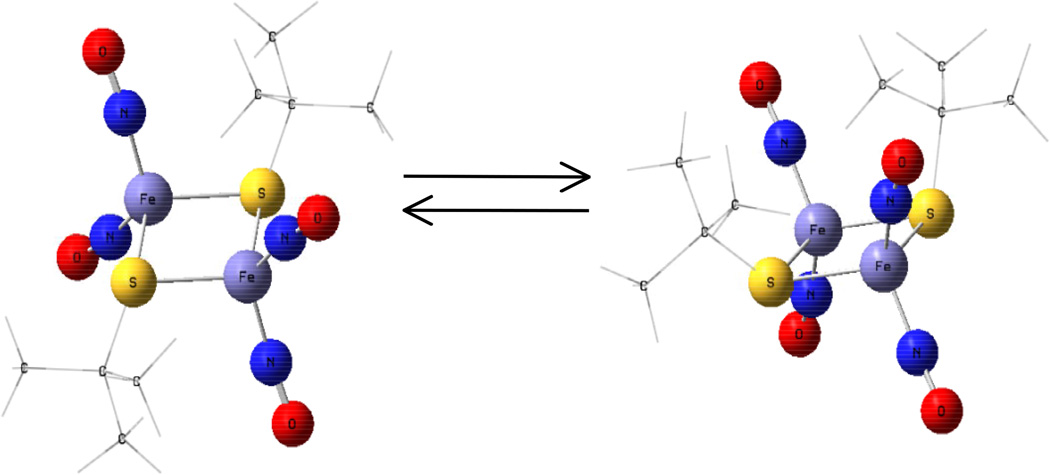

The molecular structures of complexes were determined by X-ray diffraction analysis, which showed that all four complexes crystallized as the trans- isomer (Figure 3). Further theoretical calculations on geometry optimizations using DFT were also performed on the cis-and trans- isomers and the results showed that the transformation of the cis- and trans- isomers can be easily achieved because of the very small energy difference of ∼3 Kcal/mol (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

An X-ray crystallographic representation of RRE. Hydrogen atoms are eliminated for clarity [59].

Figure 4.

Geometry optimizations using DFT showing conversion of the cis- and trans- isomers [59].

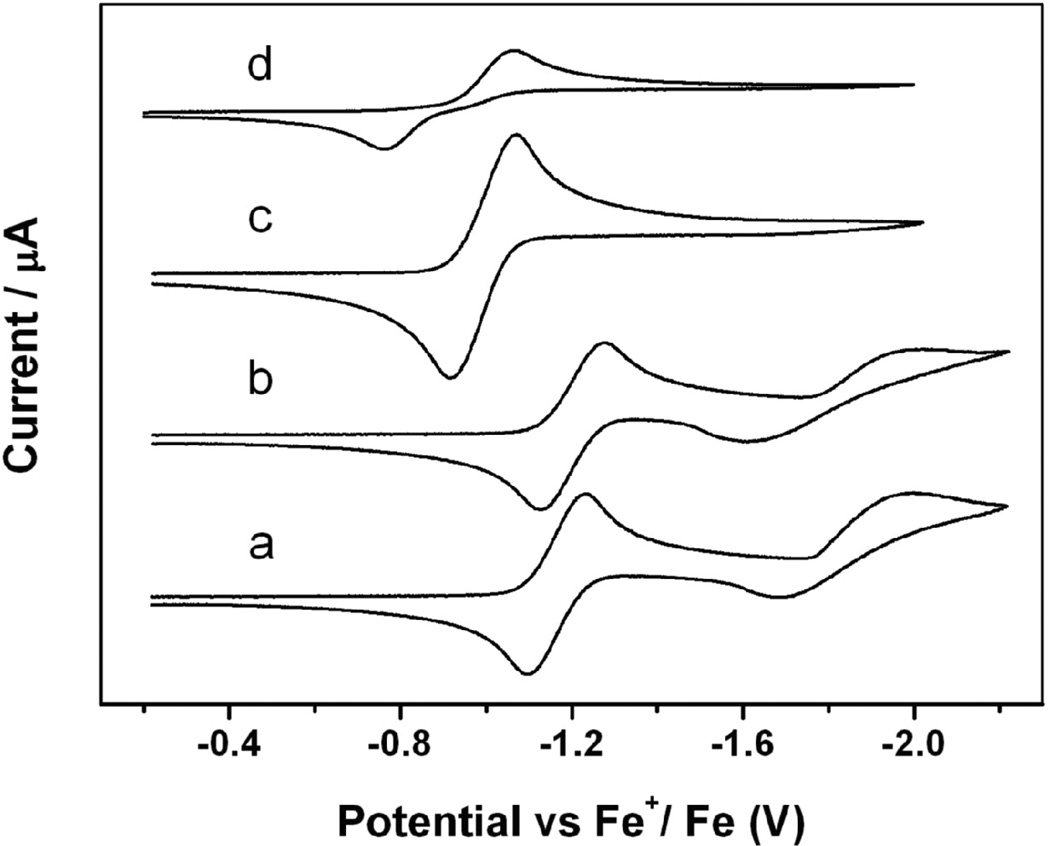

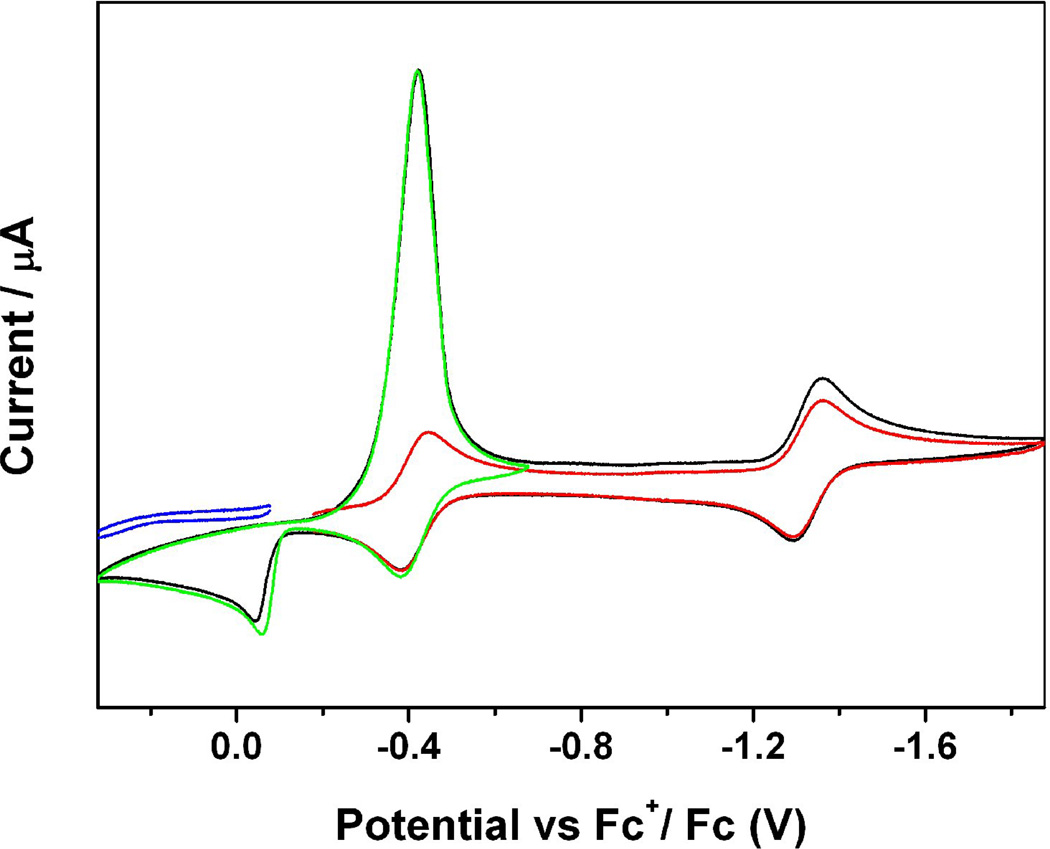

The redox behavior of these complexes was studied by cyclic voltammetry (CV) in CH2Cl2. These complexes exhibited irreversible oxidations. Complexes 2a and 2b had two quasi-reversible one-electron reductions at −1.16, −1.84 V and −1.20, −1.81 V, respectively, but complexes 2c-2d only showed one quasi-reversible one-electron reduction at −0.99 and −0.91 V, respectively (Figure 5). All of these reductions were attributed to iron-sulfur-based redox processes. The E1/2 value for the first reduction peak became more positive (easier to reduce) in the order of 2b, 2a, 2c, and 2d. This is consistent with the reduced electron donor effect of the R group in this order. These results indicate that the electronic property of the R group of RREs significantly influences the electrochemical properties of the relevant complexes.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 2 mM solution of the RRE complex 2a (a), 2b (b), 2c (c), and 2d (d) in 0.1 M [NBu4][PF6]–CH2Cl2 [59].

Using a similar method, Liaw’s group also prepared monodentate-cysteine-containing peptides KCAAK-/KCAAHK-bound RREs by the addition of 1 equiv of Fe(CO)2(NO)2 to the aqueous solution of monodentate- cysteine-containing peptide KCAAK [60]. The water-soluble dinuclear species [Fe(NO)2S(CH2)2NH3Cl]2, [Fe(NO)2S(CH2)2NH3I]2, [Fe(NO)2LCEE]2 (LCEE = L-cysteine ethyl ester hydrochloride), and [Fe(NO)2pyrim]2 pyrim = pyrimidine-2-thiol) were obtained by Berke et al., and the possibility of using these compounds for NO donor prodrugs was studied. Electrochemical methodology was used in addition to the UV-vis method, which allowed the rate of NO release to be determined as ranging from 0.63×10−5/mM to 1.62×10−5/mM [61].

Vanin recently reported that binuclear forms of DNICs with thiol-containing ligands, i.e. cysteine or glutathione, could be easily prepared in vitro by the treatment of aqueous solutions of thiols with gaseous NO in the presence of Fe2+ ions at neutral pH [62–63]. Vincent el al. also showed that the [2Fe-2S] containing spinach ferredoxin I reacted with NO at pH 6.0, and generated more protein-bound RREs in addition to DNICs because of trace amount of O2. RRE is also favored by nitrosylation in the presence of the thiolate scavenging reagent, iodoacetamide, suggesting that the role of O2 is in oxidative sequestration of cysteine thiolates [64].

2.1.2. Photolytic Properties

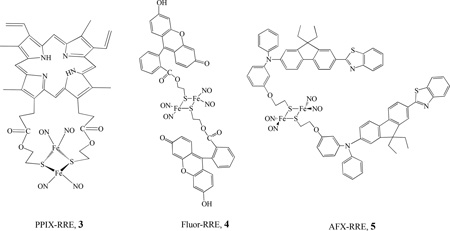

The photochemistry of various RREs was investigated by Ford’s group. The release of NO with moderate quantum yields (λ = 366 nm, ΦRES = 0.02–0.13) was observed for the series of RREs of the form Fe2(SR)2(NO)4 (where R = CH3, CH2CH3, CH2C6H5, CH2CH2OH, and CH2CH2SO3−) [65]. The RREs released ∼ 4 mol of NO per mole of cluster upon UV-vis photolysis. Nanosecond flash photolysis studies indicated that the initial photoreaction is the reversible dissociation of NO. In order to modify biological specificity and light-gathering properties, Ford’s group also designed RRE derivatives that have pendant porphyrin chromophores. By varying the R group, Ford synthesized the supermolecular complex Fe2(NO)4{(µ-S,µ-S’)P}, PPIX-RRE, 3, (where (S,S’)P is the bis(2-thiolatoethyl) diester of protoporphyrin IX, PPIX = 7,12-diethenyl-3,8,13,17-tetramethyl-2,18-porphine-dipropionic acid) [66]. The photochemical properties were investigated by both single-photon excitation (SPE) and two-photon excitation (TPE). The photoexcitation of PPIX-RRE in an aerated chloroform solution led to the photodecomposition of the cluster and release of NO with quantum yields of (5.2 ± 0.7) × 10−4 and (2.5 ± 0.5) × 10−4 for 436 and 546 nm, respectively. PPIX-RRE is a significantly more effective NO generator at longer wavelength excitation than other RREs for which R is a simple alkyl group [67].

Ford also prepared and investigated the photochemical properties of several water soluble dye derivatized Fe2(µ-RS)2(NO)4 compounds, such as Fluor-RRE, 4 [68], and AFX-RRE, 5. Under continuous photolysis, the Fluor-RRE and AFX-RRE decomposed by releasing NO with moderate quantum yields [Φ (4) = 0.0036 and ϕ (5) = (4.9 ± 0.9) × 10−3, at λirr = 436 nm]. TPE was also used to sensitize NO release from Fluor-RRE [69]. The attachment of a pendant dye chromophore as an antenna significantly improves the effective rate for photochemical NO generation, which draws the possibility of therapeutic applications of such compounds closer [70–71]. Chiou et al. also reported NO releasing and its cleavage of DNA, as well as anticancer activity of a water soluble RRE, [Fe(NO)2(µ-SCH2CH2P(O)(CH2OH)2)]2, prepared by the reaction of Fe(NO)2(CO)2 with HSCH2CH2P(O)(CH2OH)2 [72].

2.1.3. Reactions of RRE and RRS

The RRE can be reduced by adding one or two electrons forming the anionic form of RRE, [Fe2(µ-RS)2(NO)4]− or [Fe2(µ-RS)2(NO)4]2− (RRE− or RRE2–). The reduced species were prepared by the reaction of neutral [Fe2(µ-RS)2(NO)4] with a slight excess of cobaltocene or Li(BHEt3) in THF as shown in Scheme 4. The IR spectra of the monoanionic complexes [Fe2(µ-RS)2(NO)4]− showed that the corresponding νNO bands are shifted by 100 cm−1 to a lower frequency in comparison with neutral species due to the negative charge (Figure 1).

Scheme 4.

Conversion of DNIC to RRE [79].

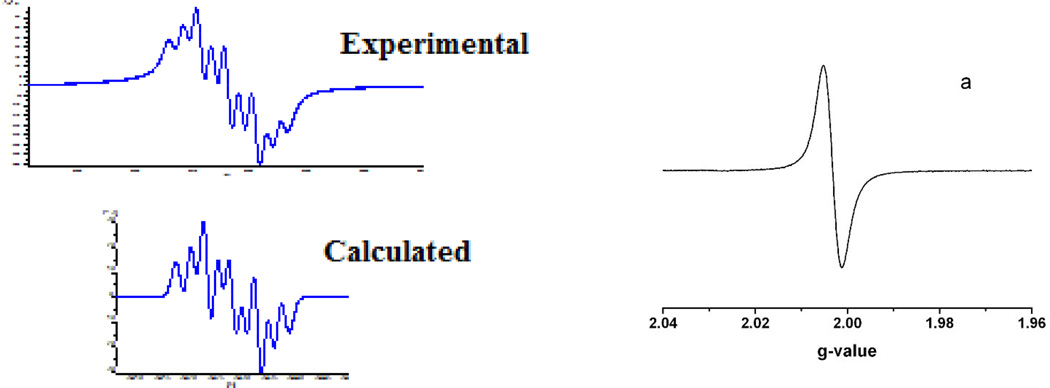

Roussin’s Red Salt Esters are diamagnetic and EPR-silent. The EPR spectra of the reduced species, [Fe2(µ-RS)2(NO)4]−, exhibited an isotropic signal at g = 1.998 ~ 2.004 without hyperfine splitting in the temperature range from 180K to 298K (Figure 6). At even lower temperatures, such as 110K, complex 2a− displayed an axial EPR signal at g┴ = 2.007 and g║ = 1.916. This is quite different from the typical DNICs. The main EPR characteristics of DNICs are the g values close to 2.03 and the hyperfine structures, which arise from the coupling between the unpaired electron and the nitrogen of the NO (14N, I = 1, 99.6% natural abundance).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the EPR spectra of a typical DNIC (experimental and simulation) recorded at 170K [174] and RRE− (a) recorded at temperatures ranging from 298–180K [59].

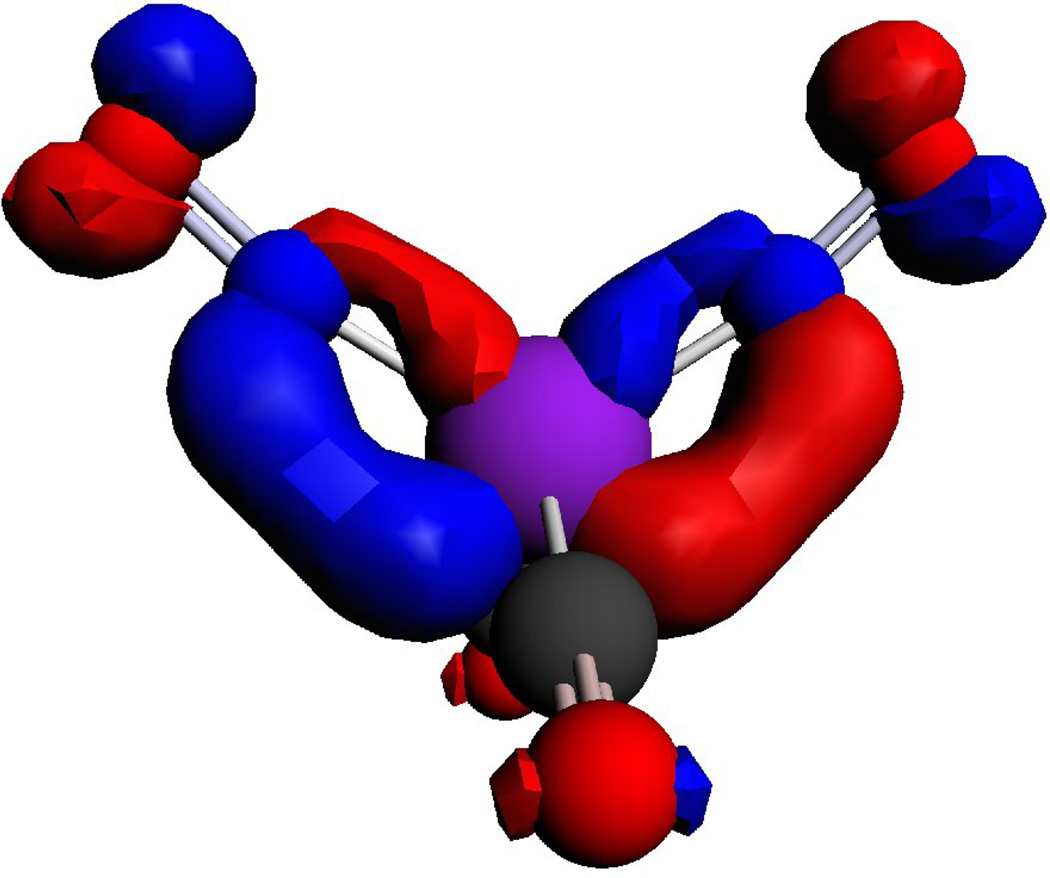

The spin density distributions of the singly occupied molecular orbit (SOMO) for the RRE− and DNIC are shown in Figure 7. For the RRE−, 60–63% of the electrons are delocalized on two irons, 25.0–25.8% of the electrons are delocalized on two sulfurs, and only 2–6% of the electrons are delocalized on four NOs. Because most of the unpaired electron density is delocalized over the Fe and S atoms and the most natural abundance of isotopes of these are 56Fe and 32S, whose nuclear spins (I) are zero, the lack of hyperfine splitting in the EPR spectra can be understood. The differences between the g values for RRE− (∼2.000) and the typical DNICs (2.03) can also be explained by the amount of electron density delocalized on Fe, which dictates the g value. The distribution of electron density on the SOMO of complex [Fe(NO)2(CO)2]+ show that Fe and NO moiety possess 54.4% and 41.8% of the electron density, respectively. The calculated distribution of electrons on the iron in DNICs (54%) is lower than the values obtained by 57Fe enriched EPR experiments on other g = 2.03 species [73] due to an over-delocalized distribution of the charge by DFT.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the distribution of electron density on the SOMO of complex RRE− and [Fe(NO)2(CO)2]+ calculated by DFT [59].

Recently, Liaw also reported the isolation of two reduced forms of RREs: [(NO)2Fe(µ-SR)2Fe(NO)2]− {R = t-Bu or Et; Cation = K(Na)-18crown-6-ether, PPN, or Me4N) [74–75].This anionic RRE− can interchange with RRE in a protic solvent (MeOH). The same group also isolated a double negatively charged RRE, [PPN]2[Fe2(µ-StBu)2(NO)2] [76]. The IR νNO stretching frequencies of [PPN]2[Fe2(µ-StBu)2(NO)2] shifted by −30 cm−1 from the reduced RRE [(NO)2Fe(µ-StBu)]2−. The UV-vis spectrum of the product displayed absorptions at 270 and 396 nm for [PPN]2[Fe2(µ-StBu)2(NO)2], while the reduced RRE [(NO)2Fe(µ -StBu)]2− displayed an intense transition absorption around 982 nm.

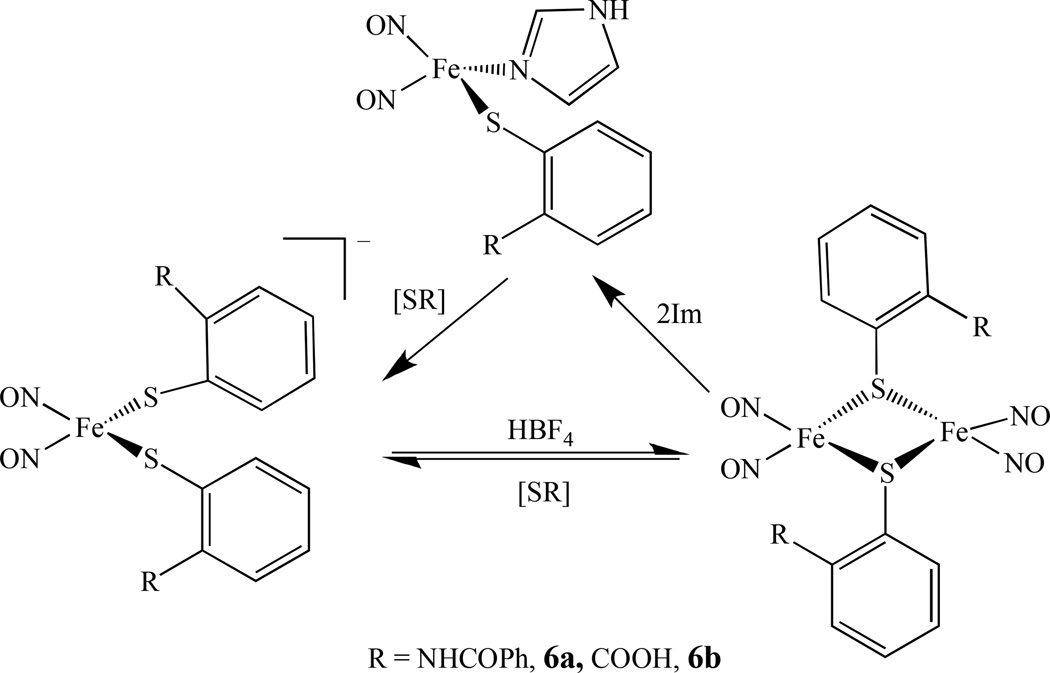

The interconversion between RREs and DNICs was investigated by Liaw’s group. They reported that the RRE [Fe(µ-SR)(NO)2]2,6, (R = C6H4-o-NHCOPh, 6a, and C6H4-o-COOH, 6b) can transform into neutral DNICs by the addition of the Lewis base [OPh]− to the THF solution [77–78]. Using a combination of EPR spectroscopy and IR v(NO) stretching frequencies, the interconversion among the neutral {Fe(NO)2}9 complex [(SC6H4-o-NHCOPh)(Im)Fe(NO)2] (Im = imidazole), the anionic {Fe(NO)2}9 complex [(SC6H4-o-NHCOPh)2Fe(NO)2]−, and the RRE was also studied (Scheme 4) [79].

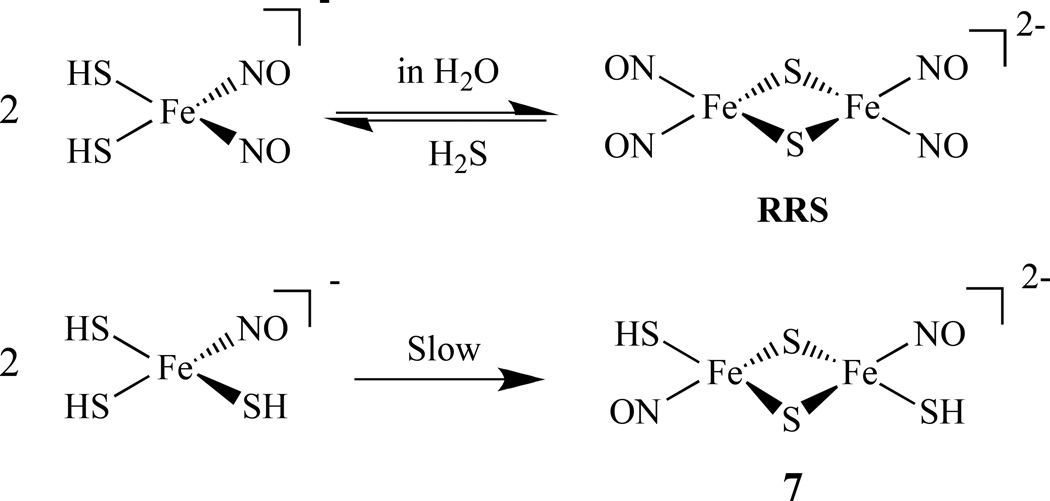

Similarly, the formation of an RRS [Fe2(µ-S)2(NO)4]2− from a DNIC in aqueous solution was observed and the transformation of RRS back to [HS]− bound DNIC was followed by releasing H2S. A similar transformation of another compound, [Fe(NO)(SH)(µ-S)]22–, 7, was also reported (Scheme 5) [80]. The reaction pathway between RRE, [(µ-S(CH2)2NH2)Fe(NO) 2]2, 8, and mixed-thiolate-containing reduced RRE [(µ-SC6H5)(µ-S(CH2)2NH3)Fe2(NO)4]−, 9, via a DNIC was also studied and revealed that it was triggered by cysteamine (Scheme 6) [81].

Scheme 5.

Conversion of DNICs to RRS and 7 [80].

Scheme 6.

The reaction pathway between RRE and a mixed-thiolate-containing reduced RRE via a DNIC [81].

2.1.4. Theoretical Calculations on RRE and RRS

Jawarska calculated the electronic structures, geometries and electronic spectra of an RRS dianion and RRE using the RB3LYP and UB3LYP methods. The electronic structure emerging from these calculations may be described as a composition of two {Fe(NO)2}9 units, in which ferric ion (S = 5/2) is antiferromagnetically coupled to two NO− ligands (each with S = 1), giving S = 1/2; the units are antiferromagnetically coupled to each other yielding a total S = 0. The S2− bridges (in RRS) or SR− bridges (RRE) mediate the antiferromagnetic coupling. The calculated spectra of RRS and RRE showed excellent agreement with the experimental spectra [82].

A detailed theoretical study of spin couplings in RRS, based on broken-symmetry density functional theory (DFT, chiefly OLYP/STO-TZP) was presented by Ghosh et al [83]. Three nitrosylated binuclear clusters were studied: [Fe2(NO)2(Et-HPTB)(O2CPh)]2+ (Et-HPTB = N,N,N',N'-tetrakis-(N-ethyl-2-benzimidazolylmethyl)-2-hydroxy-1,3-diaminopropane), [Fe(NO)2{Fe(NO)(NS))}-S,S'], and Roussin's red salt dianion [Fe2(NO)4(µ-S))]2–. These nitrosylated iron-sulfur clusters possess some exceptionally high Fe-Fe Heisenberg coupling constants (J) (J is defined by Heisenberg spin Hamiltonian: ℋ=JS(A)·S(B); J ≈ 102, 103, and 103 cm−1, respectively).

2.2. Homodinuclear Cluster Linked by Sulfur (Not RRE or RRS)

2.2.1. {M(NO)2} and {M(NO)} Centers Linked by Sulfur

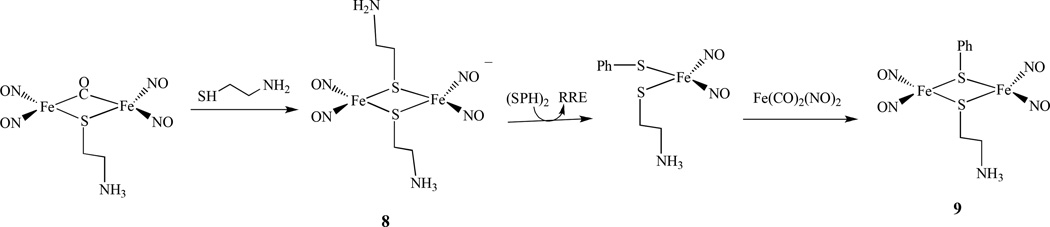

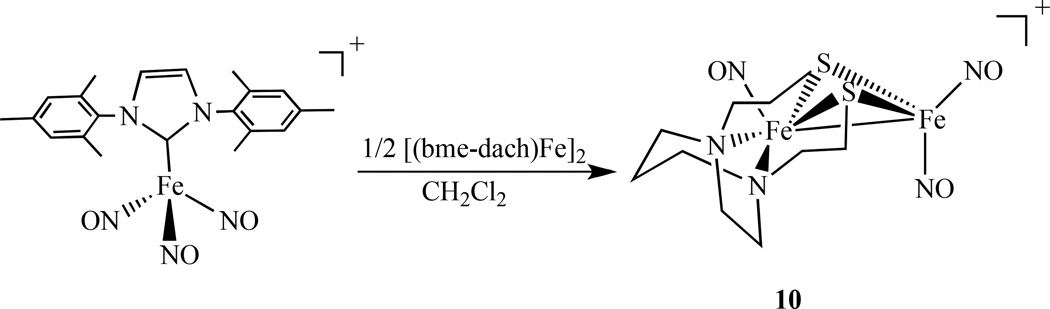

In an effort to model the active site of the [Fe-Fe] hydrogenases, homodiiron nitrosyl complexes linked by sulfur mimicking Cys-X-Cys binding of Fe(NO)2 to proteins or thio-biomolecules have been studied. Darensbourg’s group has continued using bidentate dithiolate ligands, such as N2S2 {N2S2 = N ,N′ -bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-1,4-diazacycloheptane (bme-dach) or N ,N′ -bis(2-mercaptoethyl)-1,4-diazacyclooctane (bme-daco)}, and prepared a series of diiron nitrosyl complexes. Complex [(NO)Fe(bme-dach)Fe(NO)2][BF4], 10, was obtained by direct mixing of [(bme-dach)Fe]2 with the N-heterocyclic carbene containing trinitrosyliron complex [(IMes)Fe(NO)3][BF4], [IMes =1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene] as shown in Scheme 7 [84].

Scheme 7.

Synthetic scheme for a sulfur linked dinuclear complex with {Fe(NO)2} and {Fe(NO)} centers [84].

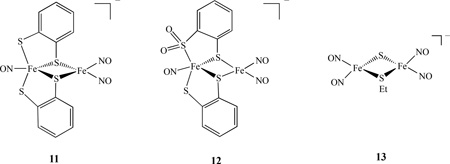

A reaction of [NO][BF4] and complex [(NO)Fe(SC9H6N)2] in a 1:1 stoichiometry led to the formation of complex (ON)Fe(µ-SC9H6N)2Fe(NO)2][BF4]. The characterization by IR, UV-vis, 1H-NMR and single-crystal X-ray diffraction indicated that the antiferromagnetic coupling between the two S= ½ {Fe(NO)}7 [S2Fe(NO)2] and [(NO)FeS2N2] cores may account for the EPR silence of the complex [85]. A few examples of asymmetric homodinuclear metal nitrosyls linked by S and SR were also reported. For instance, the diiron thiolate/sulfinate nitrosyl complexes [(ON)Fe(S,S-C6H3R)2Fe(NO)2]−, 11, (R = H, 11a, 2-Me, 11b) and [(ON)Fe(S,SO2-C6H4)(S,S-C6H4)Fe(NO)2]−, 12, were prepared by the reaction of Fe(CO)2(NO)2 and [(ON)Fe(S,S-C6H3R)2]− or [(ON)Fe(SO2,S-C6H4)(S,S-C6H4)]− in THF. Complexes 11 and 12 are best described as {Fe(NO)}7-{ Fe(NO)2}9 with electronic coupling (antiferromagnetic interaction with a J value of - 182 cm−1 for complex 11a ) to account for the absence of paramagnetism (SQUID) and an EPR signal [86]. In metal nitrosyl complexes, the Enemark-Feltham notation {MNO}x, where × represents the total number of electrons associated with the metal d and the π* (NO) orbitals, are commonly used due to the difficulty in determining the metal oxidation state [87]. Theoretical calculations by DFT method were carried out on diiron trinitrosyl complexes 10 and 11a. The ground state energetics (singlet/triplet), geometric parameters, and nitrosyl vibrational frequencies were calculated and the results showed that complex 11a is a singlet and complex 10 is a triplet, consistent with the experimental results [88].

2.2.2. {Fe(NO)2} and {Fe(NO)2} Linked by Mixed S and SR

The addition of Me2S3 (or HSCPh3) to [(NO)2Fe(SEt)2]− resulted in the formation of anionic mixed thiolate-sulfide-bridged compound [(NO)2Fe(µ-SEt)(µ-S)Fe(NO)2]−, 13 [89]. The electronic structures of 13 and the RRS were also investigated by S K-Edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy. These compounds are best described as [{FeIII(NO −)2}9-{ FeIII(NO −)2}9] according to the Enemark - Feltham notation [90].

2.2.3. {M(NO)} and {M(NO)} Linked by Sulfur

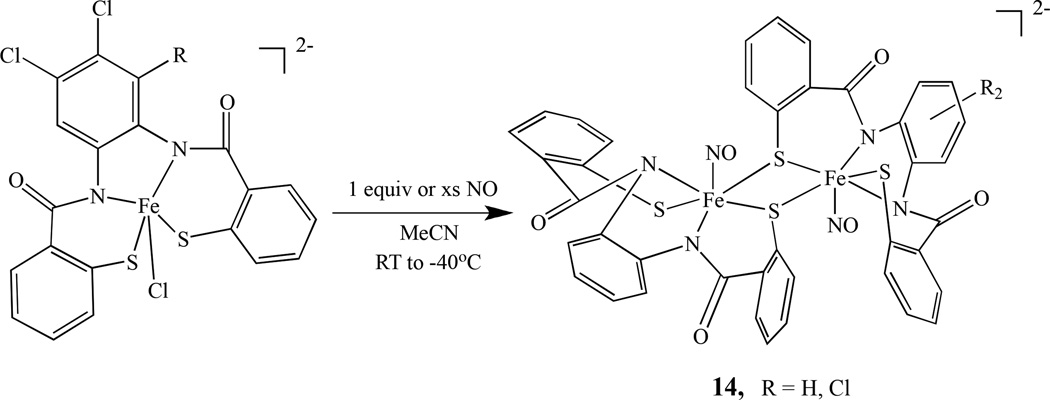

Using ligands such as PhPepSH4 and Cl2PhPepSH4, Mascharak’s group prepared two diiron mononitrosyl compounds, (Et4N)2[{Fe(PhPepS)(NO)}2], 14a, and (Et4N)2[{Fe(Cl2PhPepS)(NO)}2], 14b. They were obtained by reaction of excess NO with (Et4N)2[Fe(PhPepS)(Cl)] in aprotic solvents such as MeCN and DMF as shown in Scheme 8 [91]. The photochemical properties were also investigated and relate to the photoregulation of Fe-NHase by NO [92].

Scheme 8.

Synthetic scheme for the formation of a sulfur linked dinuclear complex with {Fe(NO)} and {Fe(NO)} centers [91].

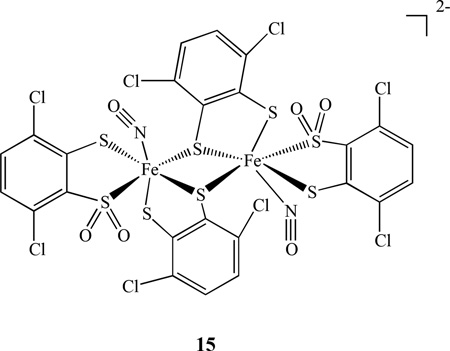

Other types of diiron mononitrosyl complexes linked by sulfur [(NO)Fe(S,S-C6H2-3,6-Cl2)2]2, 15, and [(NO)Fe(S,SO2-C6H2-3,6-Cl2)(S,S-C6H2-3,6-Cl2)] 22− were obtained from sulfur oxygenation of the five-coordinated iron-thiolate nitrosyl complex containing the {Fe(NO)}6 core [93]. The interconversions between the dinuclear complexes with the mononuclear complexes under sulfur oxygenation, redox processes, and photolysis were reported.

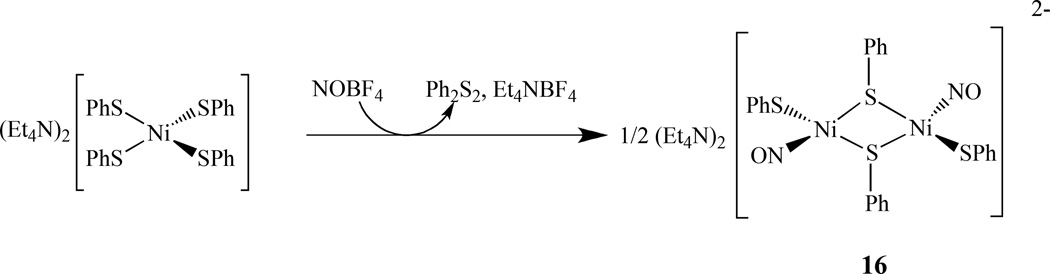

Lippard also reported a complex with two nickel mononitrosyl centers linked by a thiol ligand, (Et4N)2[Ni2(NO)2(µ-SPh)2(SPh)2], 16. It was prepared by treating a solution of (Et4N)2[Ni(SPh)4] with 1 equiv of NOBF4 in CH3CN. The reaction stoichiometry was determined as 1 equiv of Ph2S2, 1 equiv of Et4NBF4, and 0.5 equiv of (Et4N)2[Ni2(NO)2(µ-SPh)2(SPh)2] (Scheme 9) [94]. The cobalt analogs of the RRE Co2(NO)4(µ-ER)2, (ER = S-t-Bu, Se-t-Bu, S-Bu, S-Et, S-Ph) was reported by Bitterwolf’s group. They were synthesized by the reaction of organic thiol or selenol compounds with the readily prepared [Co(NO)2Cl]2. The compounds were only characterized by IR and Mass spectrometry as they are unstable in light and decompose even at a low temperature [95].

Scheme 9.

Preparation of dinuclear nickel mononitrosyl compound linked by a thiol ligand [94].

2.2.4. {M(NO)} and M Linked by Sulfur

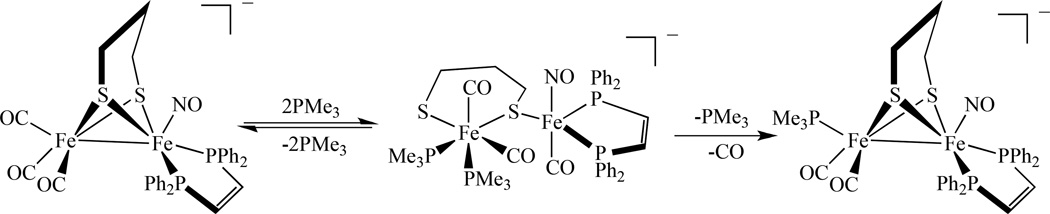

In an effort to model the active site of the diiron hydrogenases, Rauchfuss’s group reported nitrosyl derivatives of diiron dithiolato carbonyls. They were prepared starting from the precursor Fe2(S2CnH2n)(dppv)(CO)4 (dppv = cis-1,2-bis(diphenylphosphinoethylene) as shown in Scheme 10 [96]. Utilizing a S2CnH2n (n = 2, 3) ligand, the same group also synthesized a single NO bridged compound [Fe2(S2C3H6)(µ-NO)(CO)4(PMe3)2]BF4, 17 (Scheme 11). The nitrosyl complexes undergo reversible reductions at −1.5 V versus Ag/AgCl, which is ∼1 V smaller (less negative value) than those of the related CO adducts [97]. Its structural and spectroscopic features were also investigated by DFT calculations and the results show that the primary spin density is delocalized over the {Fe(NO)} unit [98].

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of diiron dithiolato carbonyl compounds with a single terminal NO [96].

Scheme 11.

Conversion of single bridged NO/CO between two iron centers [97].

2.3. Homodinuclear Nitrosyl Complexes Linked by Bisphosphines

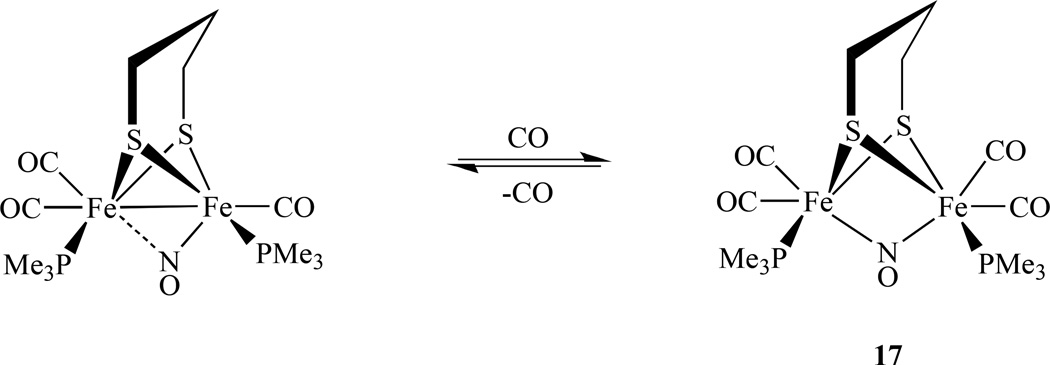

Examples of dimetallic metal nitrosyl complexes linked by bisphospines are limited compared with monometallic phosphine compounds [99–102]. One example was reported by us, in which several linear diiron species, (NO)2FeP-X-PFe(NO)2, 18, [X = CH2, 18a, C≡C, 18b, (CH2)6, 18c, and p-C6H4, 18d] were prepared from Fe(NO)2(CO)2 via addition of the desired ligand (Scheme 12). Depending on the reaction conditions employed, either linear diiron constructs connected by one bis(phosphine) linker, (NO)2FePPh2-X-PPh2Fe(NO)2, or macrocyclic species spanned by two bridging ligands, [(NO)2Fe]2(PPh2-X’-PPh2)2, 19 (X’ = CH2, 19a, C≡C, 19b), can be obtained [103]. The iron-iron distances in both the linear and macrocyclic compounds are all significantly longer than the related distances found in other structurally characterized species that are described as possessing a metal-metal bond.

Scheme 12.

Synthetic scheme for dinulear iron dinitrosyl linked by bisphosphines [103].

Based on the observed IR frequencies, the nitrosyl groups are best described as linear donating NO+ fragments. In both the solid and liquid states, the macrocyclic DPPM-supported complex exhibited four distinct IR absorptions (1733, 1721, 1687, and 1668 cm−1), while the related ten-membered ring compound containing DPPA displayed only two nitrosyl stretching signals (1723 and 1679 cm−1). This is attributed to the ring sizes which affect the interaction of the two Fe(NO)2 centers. Table 1 lists common spectroscopic data for selected compounds.

Table 1.

List of IR, UV-vis, EPR and Electrochemical Parameters of Selected Multinuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

| Complexes | IR (vNO, cm−1) | UV-Vis (nm) |

E1/2° (V) | EPR g value |

ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe2(µ-Sn-Pr)2(NO)4], 2a | 1809, 1774, 1747 (THF) 1782, 1729 (KBr) |

239(sh), 312, 363 |

−1.16, −1.84 | 59 | |

| [Fe2(µ-St-Bu)2(NO)4], 2b | 1805, 1770, 1743 (THF) 1776, 1725 (KBr) |

241, 313, 358 | −1.20, −1.81 | 59 | |

| Fe2(µ-SMePr)2(NO)4], 2c | 1818, 1786, 1755 (THF) 1796, 1728 (KBr) |

389 | − 0.99 | 59 | |

| Fe2(µ-SMe2Pr)2(NO)4], 2d | 1823, 1793, 1759 (THF) 1791, 1748 (KBr) |

237(sh), 363 | − 0.91 | 59 | |

| [Fe2(µ-Sn-Pr)2(NO)4]−, 2a− | 1673, 1655 (THF) | 1.9988 | 59 | ||

| [Fe2(µ-St-Bu)2(NO)4]−, 2b− | 1670, 1650 (THF) | 1.9988 | 59 | ||

| [Fe2(µ-SMePr)2(NO)4]−, 2c− | 1690, 1670 (THF) | 2.0036 | 59 | ||

| [Fe2(µ-SMe2Pr)2(NO)4]−, 2d− | 1693, 1674 (THF) | 2.0040 | 59 | ||

| [Fe(NO)(SH)(µ-S)]22−, 7 | 1683, 1668 (CH3CN) 1671, 1651 (KBr) |

329, 407, 585 | 80 | ||

| [(µ-S(CH2)2NH2)Fe(NO) 2]2−, 8 | 1658, 1678 (THF) | 320, 358, 452, 650, 962 |

81 | ||

| [(µ-SC6H5)(µ-S(CH2)2NH3)Fe2(NO)4]−, 9− | 1665, 1685 (THF) | 1.999 | 81 | ||

| [(NO)Fe(bme-dach)Fe(NO)2][BF4], 10 | 1795, 1763, 1740 (THF) | 84 | |||

| [(NO)2Fe(µ-SEt)(µ-S)Fe(NO)2]−, 13 | 1710, 1687 (THF) | 259, 326, 376, | −1.61 | 89 | |

| (NO)2FePPh2-CH2-PPh2Fe(NO)2, 18a | 1760, 1719, 1702 (KBr) | 103 | |||

| (NO)2FePPh2-C≡C-PPh2Fe(NO)2, 18b | 1767, 1716 (KBr) | 103 | |||

| (NO)2FePPh2-(CH2)4-PPh2Fe(NO)2, 18c | 1755, 1701 (KBr) | 103 | |||

| (NO)2FePPh2p-C5H4-PPh2Fe(NO)2, 18d | 1760, 1707 (KBr) | 103 | |||

| [(NO)2Fe]2(PPh2-CH2-PPh2)2, 19a | 1733, 1721, 1687, 1668 (KBr) | 103 | |||

| [(NO)2Fe]2(PPh2-C≡C-PPh2)2, 19b | 1723, 1679 (KBr) | 103 | |||

| [Fe2(C14H12N3S)2(NO)4], 20 | 1789, 1732 (CH2Cl2) 1781, 1715 (KBr) |

229, 287, 376(sh), 437(sh) |

105 | ||

| [Fe(NO)2(µ-OPh)]22–, 21 | 1651, 1602 (CH3CN) 1651, 1600 (KBr) |

272, 310, 381, 854 |

107 | ||

| [Fe(NO)2(µ-SC6H4-o-N(CH3)2)(µ- CO)Fe(NO)2]−, 22 |

1705, 1691 (THF) | 314, 381, 606, 975 |

108 | ||

| [Co2(NO)4(TC-6,6)], 23 | 1799, 1722 (KBr) | 382, 454, 619(sh) |

109 | ||

| [(ON)Fe(µ-S,S-C6H4)]3, 36 | 1760 (THF) 1751 (KBr) |

145 | |||

| [Co(NO)2(SPh)]3, 37 | 1844, 1819, 1780, 1764 (THF) 1840, 1817, 1779, 1744 (KBr) |

325, 421, 656 | 146 | ||

| [Fe4S4(NO)4]−, 40 | 1725 (CH2Cl2) | 2.014, 2.026, 2.049 |

169 | ||

| (PPN)2[Fe4S4(NO)6], 41 | 1700, 1668 (KBr) | 170 | |||

| [Fe4(µ3-S)2(µ2-NO)2(NO)6]2−, 42 | 1742, 1701, 1668 (CH3CN) 1739, 1702, 1685, 1668, 1510 (KBr) |

273, 343, 478 | 171 | ||

| Fe4(S3’)2(NO)8 | 1779, 1755 (THF) | 172 | |||

| Fe4(NO)8(Im-H)4, 43 | 1796, 1726 (THF) | 2.023(solid) 2.031(THF) |

174 | ||

| (Me4N)[Fe4S3(NO)7], RBS | 1799, 1744, 1710 (CH3CN) 1798, 1728, 1712 (KBr) |

265, 357, 434, 584 |

−1.09, −1.71, -2.21 |

161 | |

| [(n-Bu)4N]2[Fe6S6(NO)6], 44 | 1694 (CH3CN), 1683 (KBr) | 259, 297 | −0.04(irr), - 0.14, −1.33 |

161 | |

| [(n-Bu)4N]2[Fe6Se6(NO)6], 45 | 1698 (CH3CN), 1678 (KBr) | 288 | 0.07 (irr), - 0.33, −1.32 |

161 | |

| [Fe(BMPA-Pr)(NO)]6[ClO4], 46 | 1777 (KBr) | 255, 350, 354, 430 |

181 |

2.4. Homodinuclear Nitrosyl Complexes Linked by N/O/C

2.4.1. {M(NO)2} and {M(NO)2} Centers

The two metal nitrosyl centers can also be connected through nitrogen or oxygen atoms in addition to sulfur. Several N/O linked diiron dinitrosyl complexes [Fe2(SC6H4-o-NHC(O)Ph)2(NO)4] were obtained by varying the ligand structure slightly [104]. They were all synthesized by the reaction of Fe(CO)2(NO)2 with bis(o-benzamidophenyl) disulfide in good yield and the product was characterized by 1H NMR, IR, and UV-vis spectra.

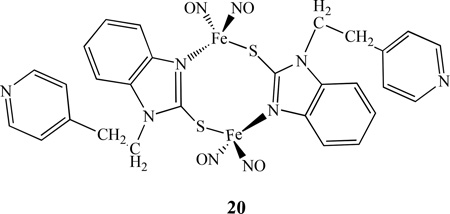

A dinuclear iron nitrosyl complex with N,S linkage [Fe2(C14H12N3S)2(NO)4], 20, was prepared by Li’s group [105]. The complex, shown in Figure 8, was characterized by IR, UV-vis, electrochemistry and single crystal X-ray diffraction. It possesses a “chair-shape” structure from the connections between two iron centers with the S-C-N frames of benzimidazole. The redox behavior of complex 20 was studied by CV in CH2Cl2 with [NBu4][PF6] as the supporting electrolyte. The complex showed irreversible oxidations, consistent with the fact that the complex is very unstable and ready to lose NO in air. Complex 20 exhibited two reversible one-electron reductions at −1.44, −2.06V, two quasi-reversible one-electron reductions at −1.02, −1.16V and one irreversible reduction at −0.72V. All of these reductions can be attributed to iron-sulfur-nitrogen-based and ligand-based redox processes. Comparing with other RREs, such as 2, complex 20 possesses more reduction processes and less negative value for the first reduction peak, showing that complex 20 is easier to be reduced as its ligand has a smaller electron donor effect. Another binuclear nitrosyl iron complex bridged by N,S ligand benzimidazole-2-thiolyl [Fe2(SC7H5N2)2(NO)4]•2C3H6O was reported by Sanina’s group. The structure and properties were studied by using X-ray, Mössbauer, IR, mass spectrometry, and SQUID-magnetometry [106].

Figure 8.

X-ray crystal structure of 20 [105].

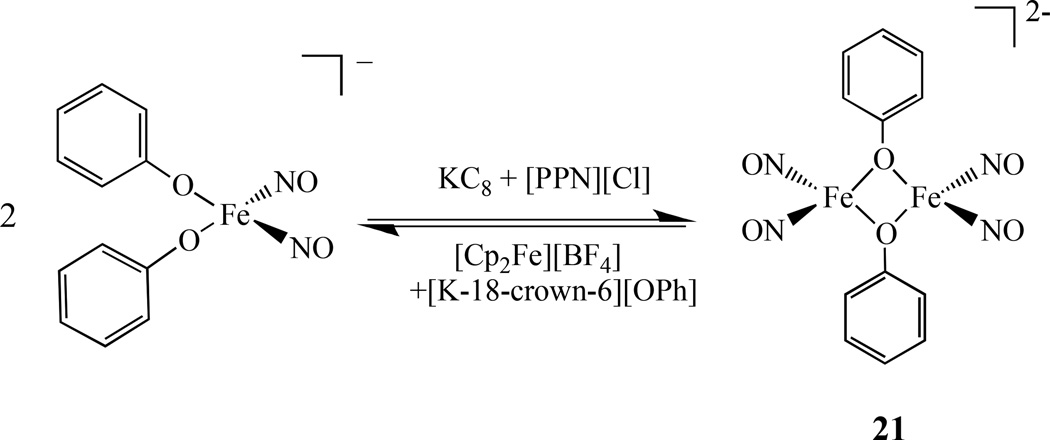

Recently Liaw reported the X-ray crystal structure of [Fe(NO)2(µ-OPh)]22− , 21, the first diiron nitrosyl linked by oxygen atom. It was prepared from [(NO)2Fe(OPh)2]− through one electron reduction (Scheme 13). Compound 21 is best described as {Fe(NO)2}10-{Fe(NO)2}10 according to the Enemark - Feltham notation. This µ-oxo diiron compound can be converted to RRE2− by addition of [St-Bu]−[107].

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of dinuclear iron dinitrosyl linked by oxygen atoms [107].

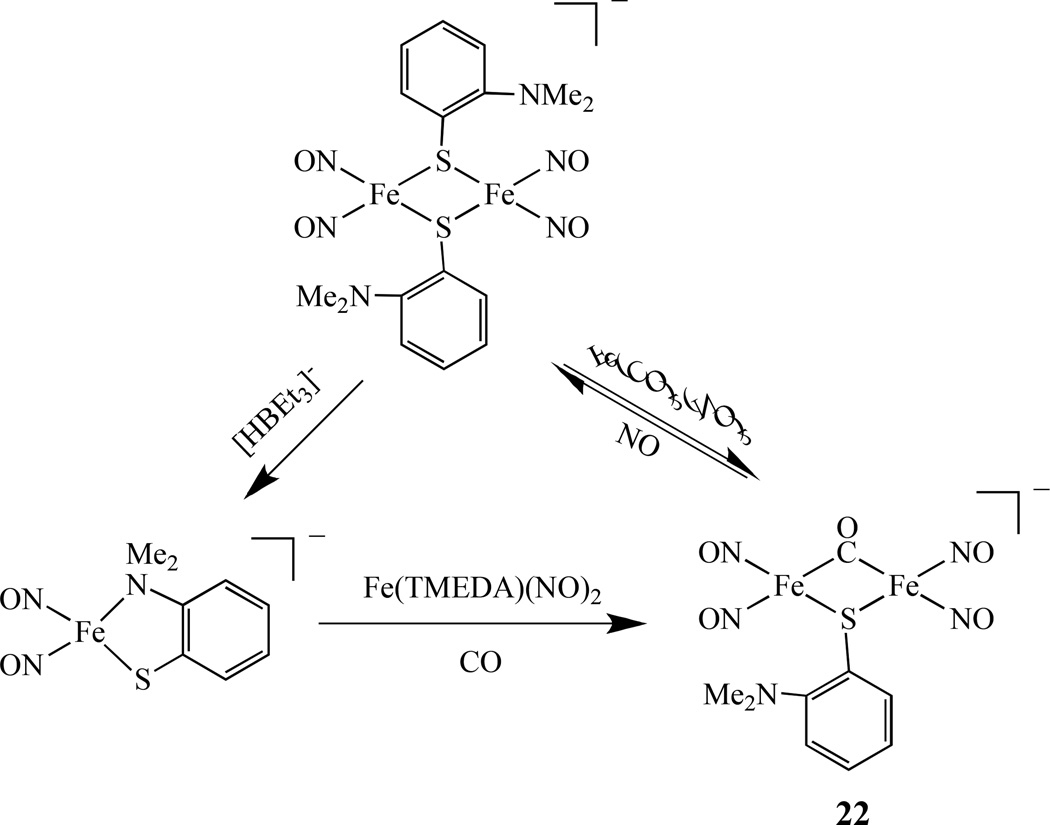

A dinuclear complex [Fe(NO)2(µ-SC6H4-o-N(CH3)2)(µ-CO)Fe(NO)2]−, 22, with mixed thiolate-CO-bridged ligands was isolated (Scheme 14) and characterized by IR, UV- vis, EPR, and X-ray crystallography [108]. This complex possesses the butterfly-like [Fe(µ-S)(µ-CO)Fe] core with a shorter Fe-Fe distance of 2.5907 Å due to the shorter Fe-S and Fe-C bond distances and is best described as [{Fe(NO)2}10-{Fe(NO)2}10].

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of dinuclear iron dinitrosyl with mixed thiolate-CO-bridged ligands [108].

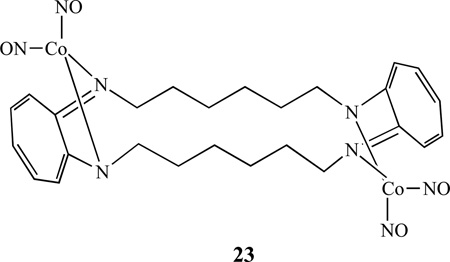

Lippard’s group also investigated reactions between cobalt(II) complexes containing tetraazamacrocyclic tropocoronand (TC) ligands and nitric oxide and reported that a bis(cobalt dinitrosyl) complex [Co2(NO)4(TC-6,6)], 23, was formed when [Co(TC-6,6)] was exposed to gaseous NO [109]. The end product depended on the ring size: in the same reaction with [Co(TC-5,5)], only the mononitrosyl complex [Co(NO)(TC-5,5)] was isolated.

2.4.2. {M(NO)} and {M(NO)} Centers

The importance of flavodiiron nitric oxide reductases (FNORs) for bacterial pathogenesis and their ability to detoxify NO has prompt scientists to investigate the mechanism of NO reduction by these enzymes [110–114]. Recently, Lehnert and co-workers reported the isolation of a diiron dinitrosyl model complex [Fe2(BPMP)(OPr)(NO)2](BPh4)2, which was prepared from treating the diferrous precursor complex [Fe2(BPMP)(OPr)](BPh4)2 with NO(g) in an anaerobic solution [115]. The crystal structure of this complex showed two end-on-coordinated {FeNO}7 units, and each iron center is coordinated by two pyridine units and shared phenolate and propionate bridges to generate a pseudo-octahedral geometry. Both {FeNO}7 units (each S = 3/2) are weakly antiferromagnetically coupled. This complex represents the first example of a functional model system for FNORs as two electrons reduction leads to the clean formation of N2O in quantitative yield. Another structurally characterized non-heme diiron dinitrosyl complex is [Fe2(Et-HPTB)(O2CPh)(NO)2](BF4)2, where Et-HPTB = N,N,N’,N’-tetrakis-(N-ethyl-2-benzimidazolylmethyl)-2-hydroxy-1,3-diaminopropane, reported by Lippard et al.[116]. Recently, on the basis of Resonance Raman and low-temperature photolysis FT-IR data, the diferrous site of an FMN-free FDP (flavodiiron protein) from Thermotoga maritima (Tm deflavo-FDP) triggering the turnover of 2NO to N2O via a NO-semibridging FeII(µ-NO)FeIII intermediate was proposed [117].

2.4.3. Organometallic Examples

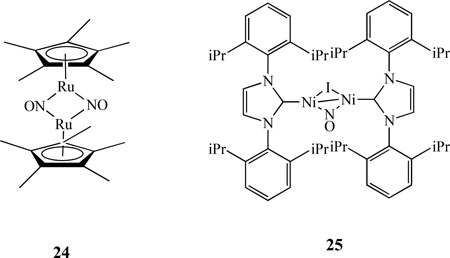

NO can coordinate with metals in either bridging or terminal fashion. The latter can also have a variety of configurations, as manifest by M-N-O angles ranging between 120 and 180°. Typically, M-N-O angles between 160–180° are considered as linear (NO+) and 120–140° are considered as bent (NO−). For example, a nitrosyl-bridged dinuclear complex [Cp*Ru(µ-NO)2RuCp*], 24, was characterized by X-ray crystallography, which revealed that the bridging nitrosyl ligands in the complex form an almost planar Ru2N2 four-membered ring with the Ru–Ru distance of 2.5366(5) Å [118]. The addition of iPrNiINO (iPr = N,N’-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazole) to 1% Na/Hg in ether (1:1 ratio) resulted in a dinuclear complex{iPrNi}2(µ-NO)(µ-I), 25 [119]. Single-crystal X-ray structure shows a relatively short Ni-Ni bond at 2.314(1) Å.

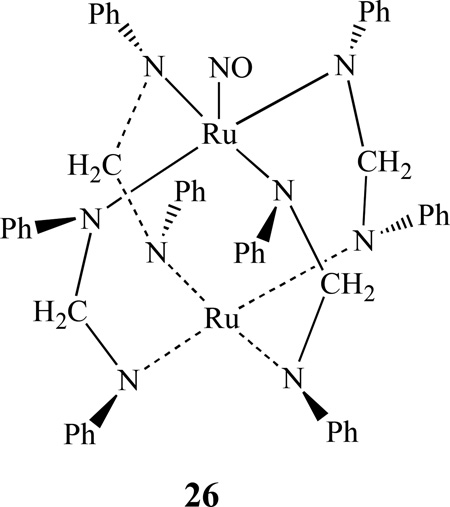

Han and Kadish reported the synthesis and X-ray crystal structures of two neutral diruthenium complexes [Ru2(dpf)4(NO)], 26, and [Ru2(dpf)4(NO)2] (dpf = diphenylformamidinate anion). Their electrochemical and spectroscopic properties were also investigated together with a reduced anionic diruthenium complex 26− through in-situ FTIR spectroelectrochemistry [120]. Recently the same group also reported the effect of axial ligands on the spectroscopic and electrochemical properties of several diruthenium compounds [Ru2(dpb)4(X)], (X = Cl, CO, NO) [121]. [Ru2(dpb)4(NO)] undergoes two successive one-electron reductions and a single one-electron oxidation, all of which involve the diruthenium unit. These two complexes were further characterized by FT-IR spectroelectrochemistry.

A bimetallic nitrosyl compound, [cat]3[Pt2(µ-pop)4(NO)] was obtained from chemical oxidation of [cat]4[Pt2(µ-pop)4] (cat+ = Bu4N+ or PPN+ = [Ph3P=N=PPh3]+; pop = pyrophosphite, [P2O5H2]2− with [NO][BF4]. The X-ray structure showed that the anion possesses the usual lantern-shaped Pt2(µ-pop)4 framework with a large Pt-Pt distance [2.8375(6) Å]; and that one of the platinum atoms has a bent nitrosyl group occupying an axial position. The X-ray photoelectron (XP) spectrum confirmed the presence of two inequivalent platinum atoms [122]. However, the nitrosyl group exhibited fluxionality on the NMR time-scale and migrated between the metal atoms at room temperature.

2.5. Heterobimetalic Nitrosyl Complexes

2.5.1. Linked by Sulfur

The heterobimetallic nitrosyl compounds ligated by sulfur atoms is of potential importance in understanding the mode of action of enzymes containing such structures at their active site, e.g. nitrogenase with its MoFe7S9 cofactor [123], hydrogenase with two iron or nickel and iron atoms bridged by two sulfurs [124–126], and nitrile hydratase with an iron or cobalt centre ligated by three cysteinyl sulfurs [127–128]. For instance, The NiFe hydrogenase from D. gigas catalyses the reversible oxidation of molecular hydrogen. This enzyme utilizes a binuclear complex as the active site, in which one Ni and one Fe atom are covalently linked by the S atoms of two cysteine residues and by one unidentified ligand [129–130]. These observations prompted many researchers to search for synthetic pathways to binuclear, µ-S thiolate bridged NiFe complexes in which NO binds to an Fe atom.

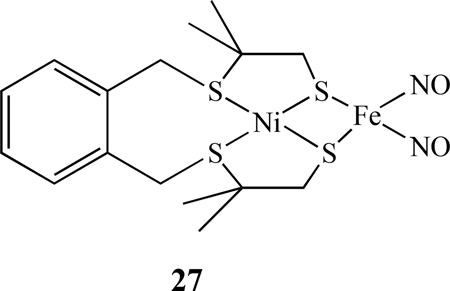

Continuing from some earlier work on heterobimetallics of nickel-iron dinitrosyl complexes [131–132], Bouwman reported that when the nickel complex [Ni(xbsms)] [H2xbsms = α,α ‘-bis(4-mercapto-3,3-dimethyl-2-thiabutyl)-o-xylene] reacted with [Fe(CO)2(NO)2], the heterodinuclear nitrosyl complex [Ni(xbsms)Fe(NO)2], 27, was isolated [133].

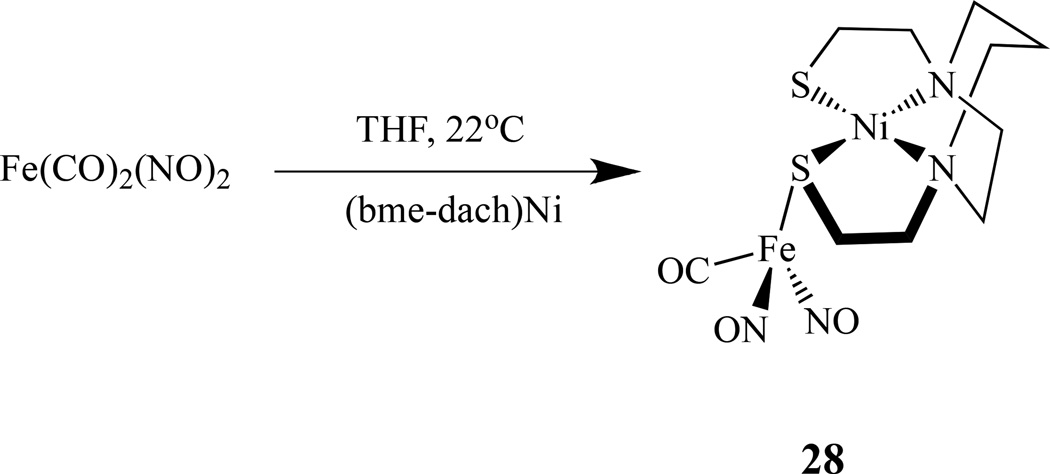

Utilizing metallodithiolates Ni(N2S2) as ligands that bear similarity in their first coordination sphere to the NHase biological site, Darensbourg’s group reported several new heterobimetallic nitrosyl compounds [134]. The reaction of Fe(CO)2(NO)2 and Ni(N2S2) (N2S2 = bem-dach) by a single CO replacement yielded [Ni(N2S2)]Fe(NO)2(CO), 28, (Scheme 15) while an excess of Fe(CO)2(NO)2 led to triply bridging thiolate sulfurs in a cluster of core composition Ni2S4Fe3 [135].

Scheme 15.

Reaction scheme showing formation of [Ni(N2S2)]Fe(NO)2(CO) [134–135].

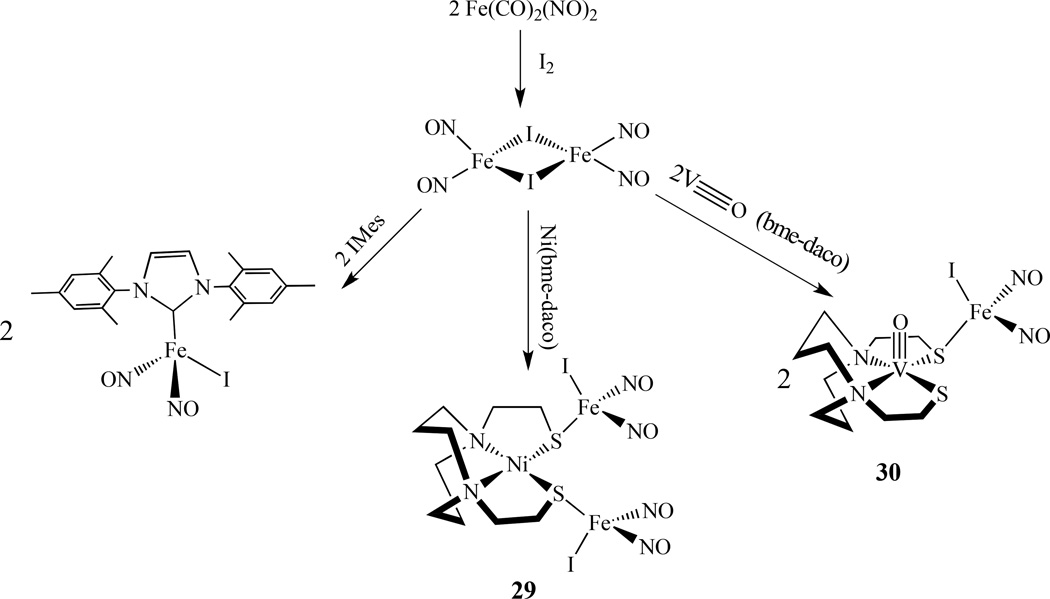

Recently, the same group also synthesized two additional compounds, {Ni(bme-daco)[Fe(NO)2I]2]}, 29, and [V≡O(bme-daco)·Fe(NO)2I], 30. They were prepared by mixing metalloligand, Ni(bme-daco) or V≡O(bme-daco) with ∼1:3 ratio of (µ-I)2[Fe(NO)2]2 in THF (Scheme 16) [136]. The EPR studies showed that both 29 and 30 are EPR silent due to strong coupling between paramagnetic centers, despite the relatively long distance of V⋯ Fe (3.75 Å). These complexes can dissociate to form the solvated (solv)Fe(NO)2I centers, which exhibit hyperfine couplings between 127I with the unpaired electron on the iron center.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of {Ni(bme-daco)·[Fe(NO)2I]2]} and [V≡O(bme-daco)·Fe(NO)2I] [136].

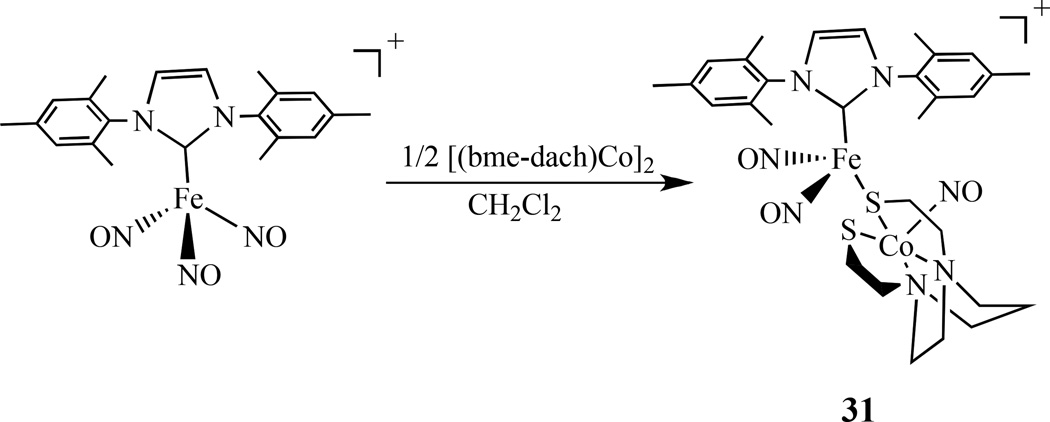

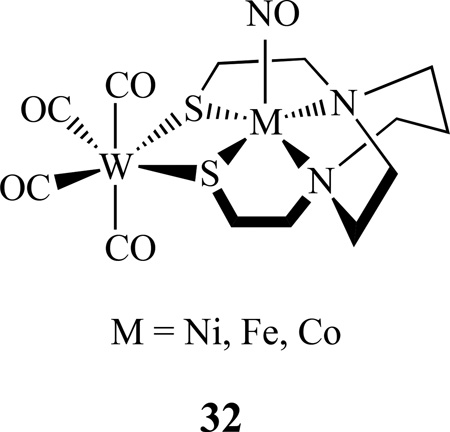

By a similar approach, the Co–Fe bimetallic complex [(NO)Co(bme-dach)(IMes)Fe(NO)2][BF4], 31, was also reported (Scheme 17) [137]. Comparing with the homobimetallic complex 10 discussed earlier, the Co-Fe distance is 3.697 Å, which is much longer than the Fe–Fe bond distance of 2.7857(8) Å in the homobimetallic complex. The addition of W(CO)4 to [(N2S2)M(NO)] (M =Ni, Fe and Co; N2S2 = bme-dach) generated [(N2S2)M(NO)]W(CO)4, 32. These complexes have two IR vibrational probes (ν(NO) and ν(CO)) for (N2S2)M(NO) complexes [138–140].

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of a {Co(NO)}–{Fe(NO)2} bimetallic complex [137].

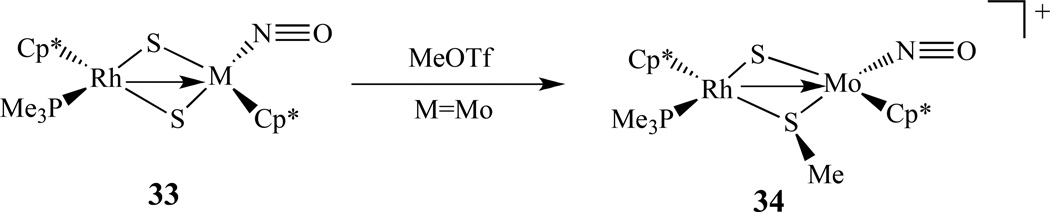

There are also some organometallic examples of bimetallic nitrosyl complexes. For instance, Ishii and co-workers synthesized a series of the bis(sulfido)-bridged heterobimetallic complexes [Cp*M(PMe3)(µ-S)2M’(NO)Cp*], 33, (M = Rh, Ir; M’ = Mo, W) from the reaction of the group 9 bis(hydrosulfido) complexes [Cp*M(SH)2(PMe3)] (M = Rh, Ir) with the group 6 nitrosyl complexes [Cp*M’Cl2(NO)] (M’ = Mo, W) in the presence of NEt3. Further methylation of the Rh-Mo complex resulted in S-methylation, giving the methanethiolato complex [Cp*Rh(PMe3)(µ-SMe)(µ-S)Mo(NO)Cp*]+, 34 (Scheme 18) [141]. Similar reactions of the group 10 bis(hydrosulfido) complexes [M(SH)2(dppe)] (M = Pd, Pt; dppe = Ph2 P(CH2)2PPh2), and [M(SH)2(dpmb)] (dpmb = o -C6H4 (CH2PPh2)2) give rise to the group 10-group 6 complexes [(dppe)M(µ-S)2M’(NO)Cp*], (M = Pd, Pt; M’ = Mo, W) and [(dpmb)M(µ-S)2M’(NO)Cp*] [142]. The Pt-W complex undergoes either S- or O-methylation to form a mixture of [(dppp)Pt(µ-SMe)(µ-S)W(NO)Cp*][OTf], and [(dppp)Pt(µ-S)2W(NOMe)Cp*][OTf], (OTf = OSO2CF3).

Scheme 18.

Examples of a heteronuclear organometallic metal nitrosyl complexes [141].

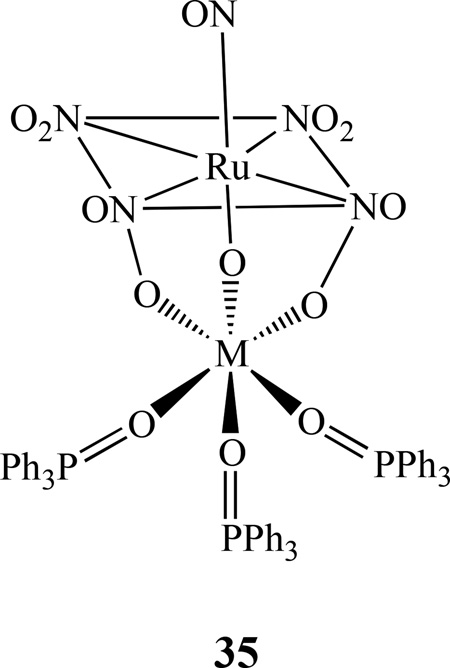

2.5.2. Linked by N/O

Kostin et al. isolated heteronuclear complexes of [RuNO(NO2)4OHM(Ph3PO)3], 35, from the reaction of nitrosotetranitrohydroxy-ruthenate ions and M2+ (M = Ni, Co, and Zn) in the presence of Ph3PO [143]. In these complexes, the distorted octahedral coordination sphere of the nonferrous metal is composed of three oxygen atoms from phosphine oxide ligands and three oxygen atoms bridging OH and NO2 groups from [RuNO(NO2)4OH]2–. Some theoretical investigations of the activation and cleavage of the N-O bond in dinuclear mixed-metal nitrosyl systems, such as [(NH2)3M–NO–M’(NH2)3], (M = Cr, or M; M’ = V or Nb) were also reported by Stranger [144].

3. Trinuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

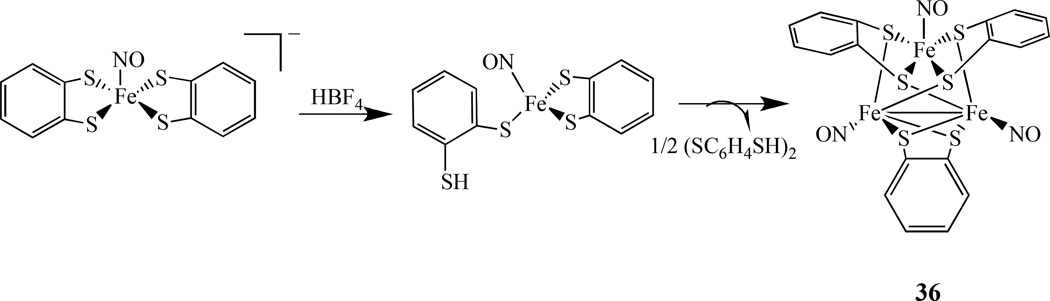

3.1. Bridged by Sulfur

There are only a few reported metal nitrosyl compounds with three metal centers. For example, Liaw et al. prepared a trinuclear iron-thiolate-nitrosyl complex containing a core of Fe3S6. The neutral trinuclear iron-thiolate-nitrosyl, [(ON)Fe(µ-S,S-C6H4)]3, 36, was synthesized by the protonation of the mononuclear iron-thiolate-nitrosyl [PPN][(NO)Fe(S,S-C6H4)2] by HBF4 in THF (Scheme 19) [145]. The cationic species [(ON)Fe(µ-S,S-C6H4)]3[PF6] obtained from the oxidation of this complex is diamagnetic. Various spectroscopic (IR, UV-vis, EPR, NMR), magnetic, and Fe/S/N K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements indicated that the unpaired electron is mainly allocated in one of the iron atoms and is best described as {Fe(NO)}7.

Scheme 19.

Synthesis of a trinuclear iron-thiolate-nitrosyl compound [(ON)Fe(µ-S,S-C6H4)]336 [145].

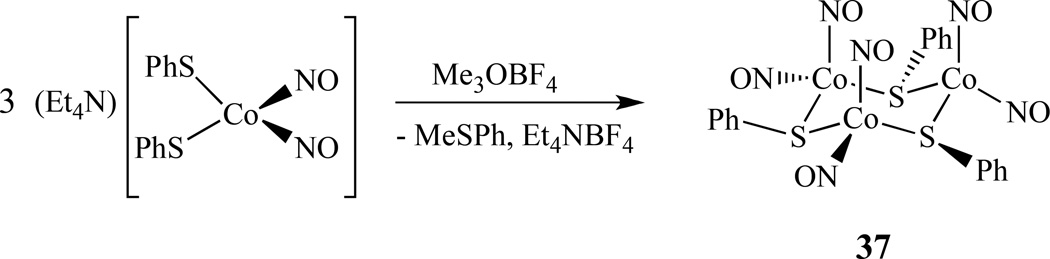

Recently, Lippard and co-workers reported the isolation of a trimetallic cobalt nitrosyl complex [Co(NO)2(SPh)]3, 37. It was prepared by the addition of stoichiometric Me3OBF4 to (Et4N)[Co(NO)2(SPh)2] in CH3CN (Scheme 20) [146]. This compound is diamagnetic, with structural parameters and spectroscopic features similar to that of Roussin’s black salt, RBS.

Scheme 20.

Synthesis of trimetallic cobalt nitrosyl complex [Co(NO)2(SPh)]3 [146].

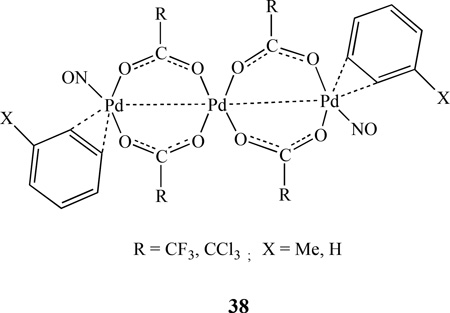

3.2. Bridged by N/O/C

A series of linear trinuclear palladium nitrosyl complexes with η2-coordinated arene molecules having formula of Pd3(NO)2(µ-RCO2)4(η2-arene)2, 38, (R = CF3, arene = toluene, R = CCl3, arene = benzene) was reported by Sromnova [147–148]. The substitution of arene by η2 - coordinated alkenes generated Pd3(NO)2(µ-CF3CO2)4(η2-L)2, (L = Me3CCH=CH2, CH2=CHPh) and Pd4(µ-NO)2(µ-CF3CO2)4(η2-CH2=CHPh)4. X-ray diffraction analysis showed that the metal atoms form a linear chain in which each terminal atom is linked to the central atom via two bridging trifluoroacetate groups. The nitrosyl ligands are coordinated to the terminal palladium atoms in a bent end-on fashion [149].

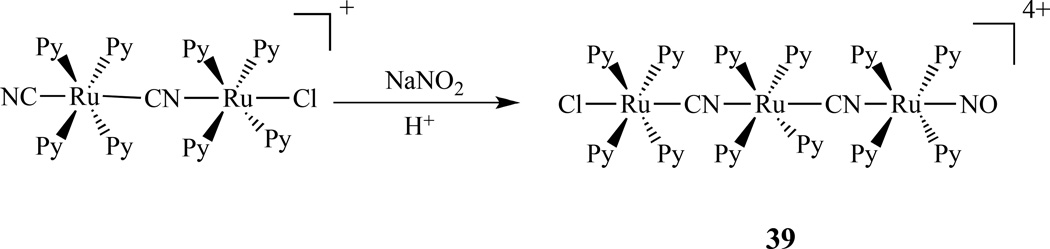

Earlier work by Slep showed that the {RuNO}6 fragment could be incorporated into a dinuclear species that behaved as a donor acceptor (D–A) system, similar to the mixed-valent systems [150]. Continuing this work, the same group reported a linear homotrinuclear compound trans-[ClRu(py)4(NC)Ru(py)4(CN)Ru(py)4(NO)](PF6)4, 39, which was prepared by reaction between the nitro complex trans-[(NC)Ru(py)4(CN)Ru(py)4(NO2)]+ and the solvento complex obtained by reaction between [ClRu(py)4(NO)]3+ and N3− in acetone (Scheme 21). The new complex was investigated through spectroscopic methods, spectroelectrochemistry, and supplemented by DFT calculation. The one-electron reversible reduction at 0.49 (acetonitrile) or 0.20 V (water) vs AgCl/Ag is centered on the nitrosyl moiety, while oxidation at 0.71 or 0.57 V vs AgCl/Ag occurs on the chlororuthenium side of the molecule [151].

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of a homotrinuclear compound trans-[ClRu(py)4(NC)Ru(py)4(CN)Ru(py)4(NO)](PF6)4 [151].

4. Tetranuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

4.1 Linked by Sulfur

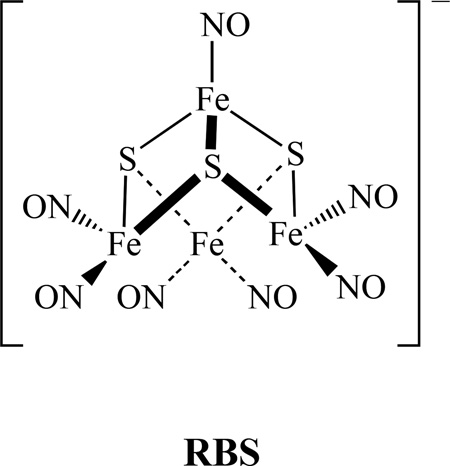

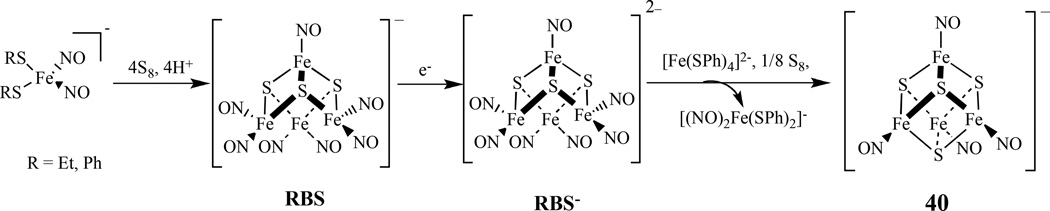

The most commonly studied tetranuclear metal nitrosyl compounds are the Roussin’s black salt (RBS) type clusters. It was first produced by the reaction of nitrous acid, potassium hydroxide, potassium sulfide, and iron(II) sulfate in aqueous solution [152]. RBS is well known as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent that has been used for more than 100 years to combat pathogenic anaerobes. It consists of four irons, three sulfurs, and seven nitrosyls, as shown below. It is one of the few iron-sulfur clusters that possess the sulfur-voided [Fe4S3] cuboidal subunit found in the FeMo cofactor of nitrogenase [153].

4.1.1. Biological Activities of RBS

Roussin’s black salt is a nitric oxide donor. The NO donated by RBS has proven to be toxic to some melanoma cancer cells [154]. Since the discovery that RBS causes rapid relaxation of smooth muscle cells in the taenia coli upon photon release of NO [155], there have been many studies related to the biological activities of RBS [156]. For instance, RBS releases approximately 3.7 moles of NO per one mole of RBS after irradiated with UVA (300–420 nm, max 354 nm, 2.0mW/cm2) for 5–30 min. Both short- and long-term effects of photogenerated NO were investigated on the two neoplastic cell lines: human (SK-MEL188) and mouse (S91). Exogenous NO from the RBS is toxic to cells in a dose-dependent manner. NO and its short-lived metabolites are responsible for cellular death. The RBS in dark is toxic to those cancer cells at concentrations above 1 µM. The antimicrobial activity of the RBS on the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyococcus furiosus was also reported [157].

In addition, it is known that iron–sulfur clusters react with NO to regulate intracellular iron levels, and the oxidative stress response involves degradation of the clusters to generate protein-bound or low-molecular-weight dinitrosyliron complexes, which can trigger protein conformational changes by binding these proteins to DNA and other cellular targets [158]. Several of the regulatory proteins known to respond to NO contain iron-sulfur clusters that function as the sensory module [159].

4.1.2. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Properties of RBS

It is known that RBS can be synthesized by the conversion of RRS in mildly acidic conditions. This reaction is reversible and RRS can be reformed upon alkalization of the reaction solution. Liaw recently showed that dinitrosyl iron complexes [E5Fe(NO)2]− (E = S, Se) could also serve as a precursor of Roussin’s black salt [Fe4E3(NO)7]− and the conversion can be achieved by adding acid HBF4 or oxidant [Cp2Fe][BF4] in THF [160].

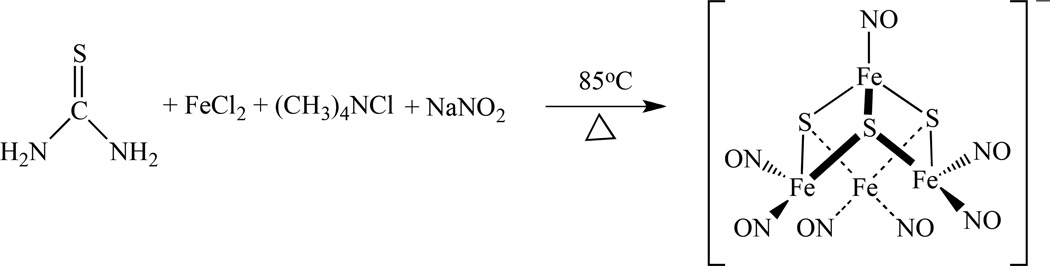

Recently, we reported a new solvent-thermal method to prepare RBS. A tetranuclear cluster (Me4N)[Fe4S3(NO)7], was isolated from heating a mixture of FeCl2 4H2O, thiourea, (CH3)4NCl, and NaNO2 in methanol at 85°C for 48 hours, as shown in Scheme 22 [161].

Scheme 22.

Solvent-thermal synthesis of a tetranuclear cluster (Me4N)[Fe4S3(NO)7] [161].

The IR spectrum of this complex showed three stretching frequencies at 1799, 1744 and 1710 cm−1. The CV of the compound had three quasi-reversible reductions with half-wave potentials of −1.09, −1.71, and −2.21 V vs ferrocene/ferrocenium ion in 0.1 M (NBu4)(PF6) in CH3CN. X-ray crystal structure of the complex showed the average Fe-Fe distance is 2.705 Å, which is clearly shorter than the relevant value of 2.764 Å for dianion [Fe4S3(NO)7]2−. This difference was explained by the antibonding character of the HOMO of [Fe4S3(NO)7]2−. However, the counter ion showed no effect on the structure parameters.

Sheppard et al. summarized the characteristics of vibrational spectra for various modes of NO bonding to metal clusters with relation to the X-ray structures. Some of the factors examined were: modes of bonding, charge, electron withdrawing co-axial groups, solvents, etc [162]. In addition to the values of ν(14NO) themselves, the isotopic band shift—{defined as [ν(14NO)-ν(15NO)]}, and the isotopic band ratio [ν(15NO/ν14NO)], could also be used as criteria to distinguish between linear and bent NO groups.

Using semi-empirical quantum chemical methods, Stasicka’s group calculated possible products for reactions of the RBS anion and a series of pseudo-cubane complexes with S-donor or N-donor ligands [163]. The results justify the hypothesis that a pseudo-cubane adduct, [Fe4(µ3-S)3(µ3-SR)(NO)7]2− will form. The same group also reported the calculations of the electronic structure, geometry, and electronic spectra of the RBS anion using the RB3LYP and UB3LYP methods [164]. A detailed theoretical study of spin couplings in RBS, based on broken-symmetry density functional theory (DFT, chiefly OLYP/STO-TZP) calculations, was presented by Ghosh et al. [83] The electronic structure of the RBS may be described as composed of the one {Fe(NO)}7 unit, in which ferric ion (S = 5/2) is antiferromagnetically coupled to a NO− ligand (S = 1) giving S = 3/2; such a unit is antiferromagnetically coupled to three {Fe(NO)2}9 units, each of which is formed by a ferric ion (S = 5/2) antiferromagnetically coupled to two NO− ligands with S = 1. The resulting total spin of RBS is S = 0. The S2− bridges mediate the antiferromagnetic coupling. The calculated UV-vis transitions were mainly of charge transfer character, that is consistent with the experimental observations.

4.1.3. The RBS Identified from the Reaction of NO with [Fe-S] Clusters

It is known that [4Fe-4S] clusters serve as targets of reactive nitrogen oxide species in biology; thus researchers have used natural [4Fe-4S] proteins to investigate these reactions. For instance, in one study using recombinant Pyrococcus furiosus ferredoxin (D14C mutant), the EPR-silent [Fe4S3(NO)7]− was detected as the major product by nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS) [165]. Using combination of NRVS and EPR-spectroscopic techniques, Lippard and others showed that the major products in nitrosylating specific [Fe-S] proteins are the diamagnetic species, e.g. RRE, RRS, or RBS, in addition to the DNIC with a characteristic EPR signal g = 2.03 [166].

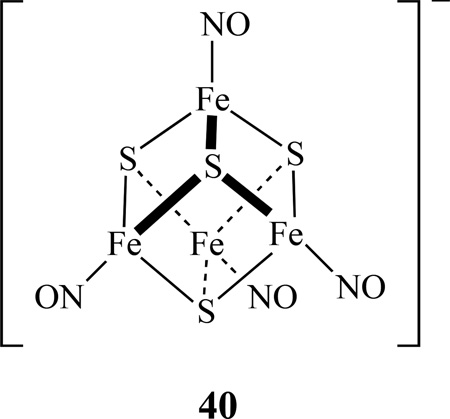

Using synthetic model [4Fe-4S] clusters, possible pathways for the reactions of iron-sulfur clusters with nitric oxide in biological systems have been studied. Lippard reported that [Fe4S4(SR)4]2− (R = Ph, CH2Ph, t-Bu, or 1/2 (CH2)-m-C6H4) reacts with NO(g) and proceeds in the absence of added thiolate to yield a RBS [167]. In contrast, (Et4N)2[Fe4S4(SPh)4] reacts with NO(g) in the presence of 4 equiv of (Et4N)(SPh) yielding the expected DNIC. Recently, Lippard also prepared site-differentiated synthetic models for the biological [4Fe-4S] clusters [Fe4S4(LS3)L′]2− (LS3 = 1,3,5-tris(4,6-dimethyl-3-mercaptophenylthio)-2,4,6-tris(p -tolylthio)benzene; L′ = Cl, SEt, SPh, N3, 2-SPyr, Tp, S2CNEt2) and studied their reactivity toward NO(g) and Ph3CSNO [168]. In all cases, the reactions proceed via formation [Fe4S4(NO)4]−, 40, (S = 1/2) species, which ultimately converts to RBS.

The transformations between DNICs with iron sulfur nitrosyl clusters were investigated [169]. A reaction of [(NO)2Fe(SR)2]− (R = Et, Ph) with S8 and HBF4 yielded RBS, which was reduced by [Na][biphenyl] to generated reduced RBS−, [Fe4S3(NO)7]2− , which further converted into complex 40, along with byproduct [(NO)2Fe(SR)2]− upon treating with [Fe(SPh)4]2− and S8 (Scheme 23). This tetranuclear cluster, 40, was characterized by IR, UV-vis, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Scheme 23.

Conversion between DNIC, RBS, reduced RBS [Fe4S3(NO)7]2− , and [Fe4S4(NO)4]2− [169].

4.1.4. Other Tetranuclear Complexes Linked by Sulfur (Not RBS)

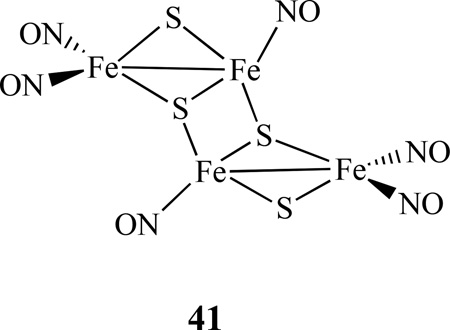

Two methods of making (PPN)2[Fe4S4(NO)4] were reported by Coucouvanis [170]. One is by using a 1:2 ratio of (PPN)[Fe4S3(NO)7] and (PPN)2[Fe4(CO)13] in MeCN, followed by the addition of Bu4NSH, and heating the mixture under reflux for 24 h. Another method is to add excess of Bu4NSH in (PPN)2[Fe8S6(NO)8] in DMF and heated at 80 °C for 24 h. The same group also isolated a tetrasulfidotetrairon-hexanitrosyl cluster (PPN)2[Fe4S4(NO)6], 41. It was synthesized by mixing (NH4)[Fe4S3(NO)7] and (PPN)2[Fe4(CO)13] in ∼1:2 ratio in MeCN and followed by the addition of Bu4NSH. The mixture was allowed to react for 8 h at −20 °C to isolate the product.

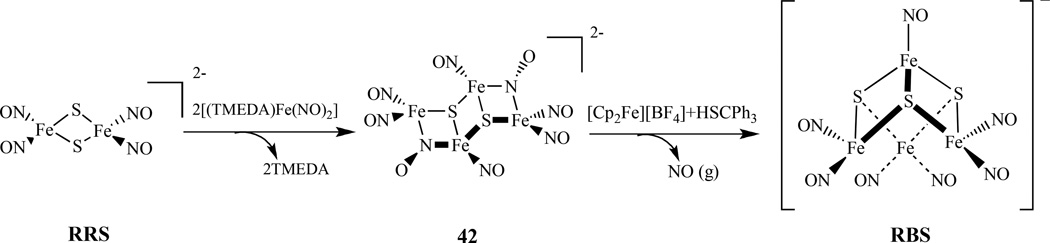

Liaw et al reported synthesis of [Fe4(µ 3-S)2(µ 2-NO)2(NO)6]2− , 42, through the reaction of [Fe2(µ2-S)2(NO)4]2− with two equiv. of [(TMEDA)Fe(NO)2] (TMEDA = tetramethylethylenediamine) in CH3CN (Scheme 24). The Fe4S2NO8 complex posesses both bridging and terminal NO ligands [171]. The complex 42 with semi-bridging nitroxyls acts as a key intermediate in the transformation of the RRS into RBS. The IR νNO and 15N NMR spectra recorded at various temperatures indicated that this complex is fluxional, scrambling terminal and bridging NO ligands at an elevated temperature. Such a fluxional behavior was also noticed earlier in a triiron hexanitrosyl cluster [73].

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of [Fe4(µ3-S)2(µ2-NO)2(NO)6]2− 42, from RRS and a proposed conversion of 42 to RBS [171].

Utilizing a chelating ligand, Darensbourg reported that the reaction of PPN[FeI2(NO)2] with Na2S3’ (S3’ = S(CH2)2S(CH2)2S) in a 1:1 mixture of MeOH/THF resulted in a tetranuclear Fe4(S3’)2(NO)8 and its structure was established by X-ray crystallography [172]. Le Brun and co-workers proposed the formation of a tetranuclear octanitrosyl complex [Fe4(NO)8(Cys)4] (Cys = systeine) from the nitrosylation reaction of the [4Fe-4S] cluster of WhiB-like proteins. Further DFT calculations based on model complexes indicated that such a species may be stable [173].

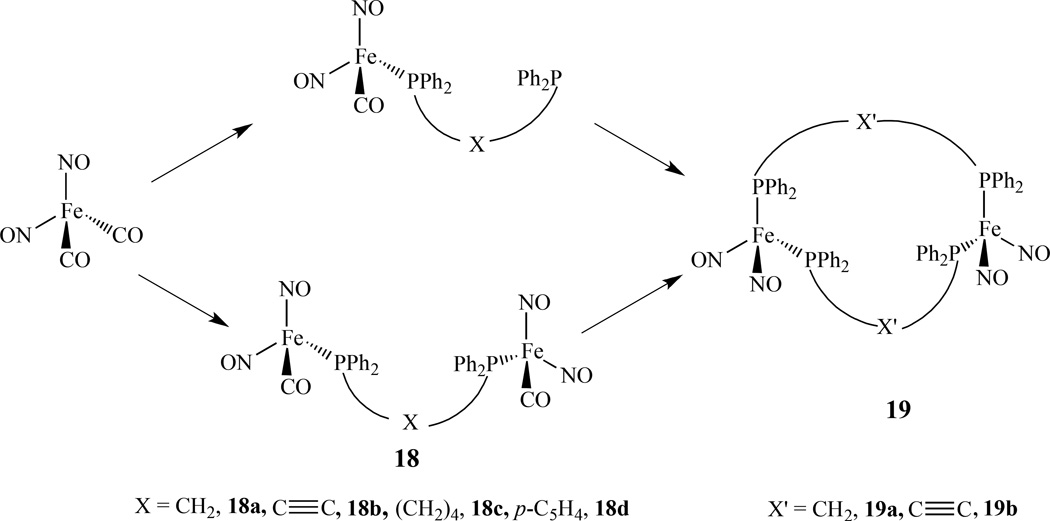

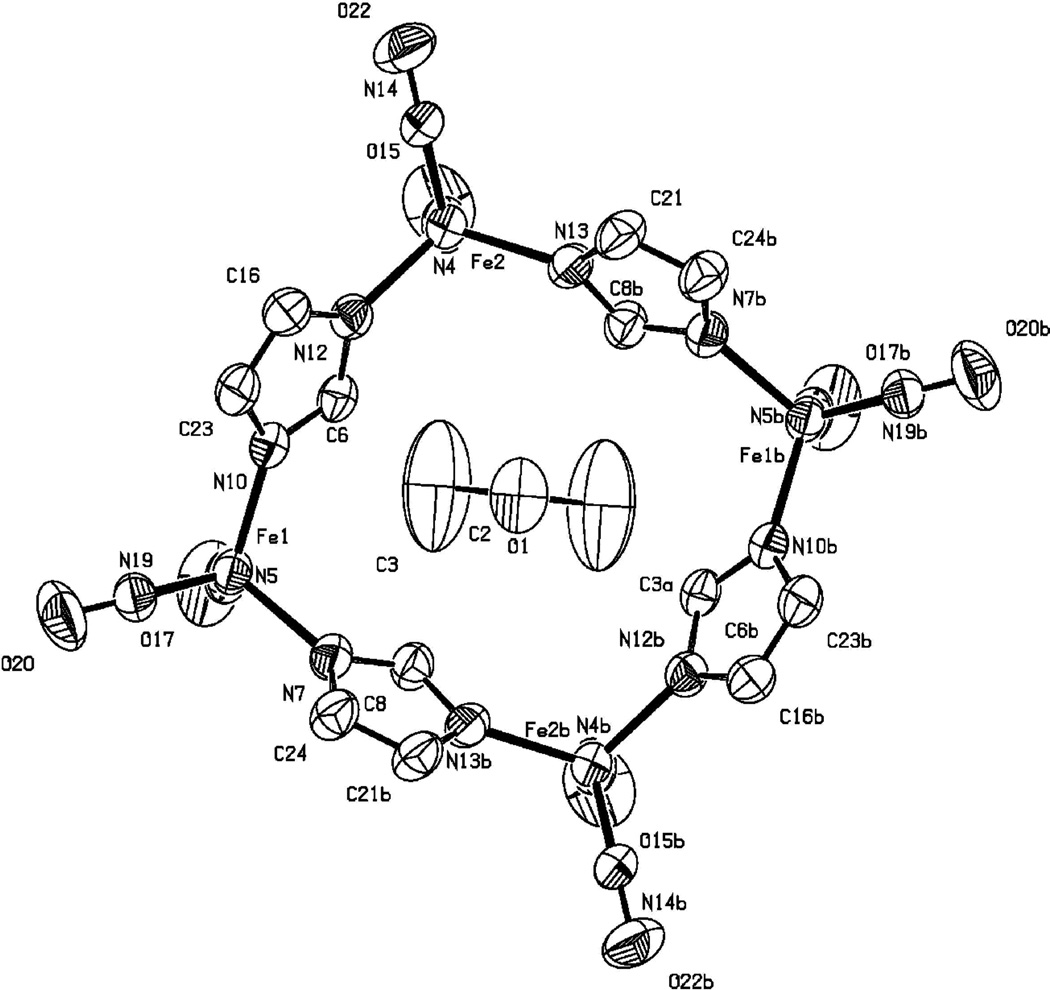

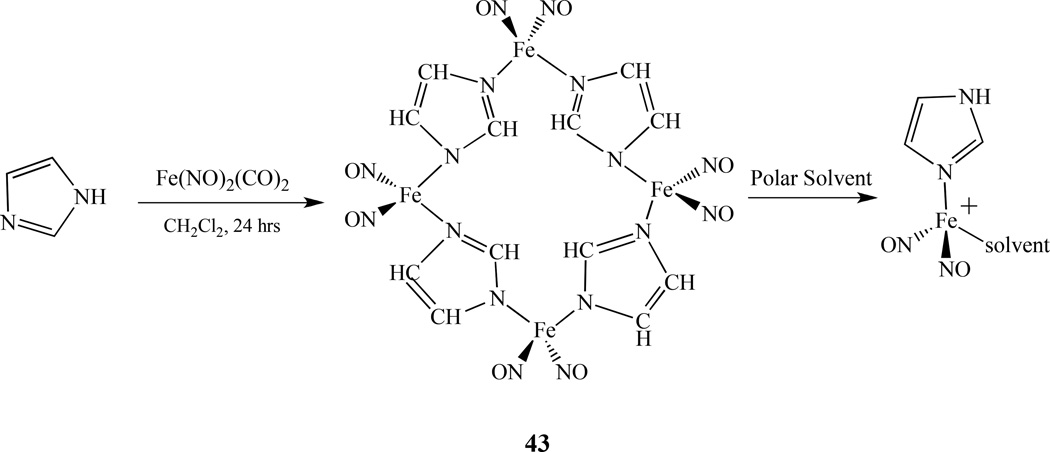

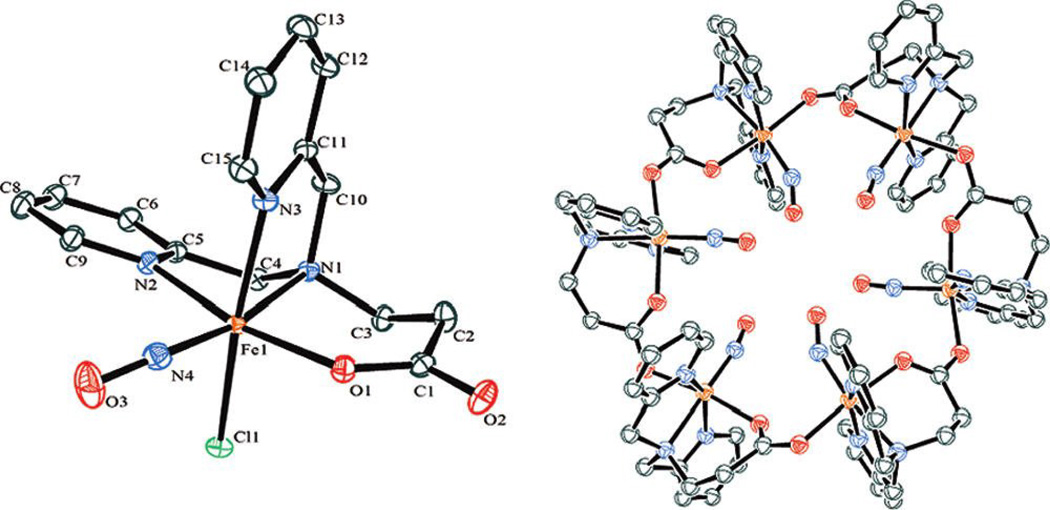

4.2. Linked by N/O/C

The first tetranuclear nitrosyl complex linked by nitrogen atoms, Fe4(NO)8(Im-H)4, 43, was reported by Li and Ford. It was synthesized by mixing one equivalent of Fe(NO)2(CO)2 with two equivalents of imidazole (Im) in methylene chloride at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere [174]. Two similar complexes [(2-isopropylimidazole)Fe(NO)2]4 and [(benzimidazole)Fe(NO)2]4 were prepared by Darensbourg [175]. The X-ray crystal structure shows four iron centers that are linked together through four deprotonated imidazole bridging ligands forming a neutral 16-membered rhombic macrocycle with alternating imidazolates and irons as shown in Figure 9. Each iron center possesses a pseudo-tetrahedral geometry and is coordinated to four nitrogen atoms–two from the nitrosyl ligands and two from the imidazolate ligands (Im-H). The molecule has dimensions of 8.18 × 8.70 Å (Fe1⋯Fe1 × Fe2⋯Fe2). A solvent molecule, acetone, is crystallized inside the cavity.

Figure 9.

X-ray crystal structure of 43 with anisotropic thermal displacement ellipsoids drawn at 50% [174].

The nitrosyl stretching frequencies vNO occur at 1796 cm−1 and 1726 cm−1, that is even higher than single substituted analog Fe(NO)2(CO)(IM), suggesting that the oxidation of the Fe(NO)2 units took place to balance deprotonation of the bridging ligands. The observed νNO makes complex 43 {Fe(NO)2}9, which is consistent with the data obtained from the Mössbauer measurement. The EPR and solution IR studies in polar solvents show that the tetrameric molecule is fragmented and solvated to give Fe(NO)2(Im-H)(THF) or its protonated analog seventeen electron species [Fe(NO)2(Im-H)(THF)]+ as shown in Scheme 25. The characteristic g value close to 2.03 and the small hyperfine coupling constants (2 – 3 G) indicate that the unpaired electrons are localized on the Fe center. Nitric oxide release from this tetrameric complex was studied by thermo methods which showed stepwise loss of NO between 100–140°C, 180–220°C, 340–420°C, and 480- 520°C.

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of a tetranuclear nitrosyl complex linked by nitrogen atoms, Fe4(NO)8(Im-H)4 43, and it’s conversion to solvated species [174].

Stromnova reported a series of tetranuclear palladium nitrosyl carboxylate complexes, Pd4(µ-NO)2(OCOR)6, (R =/CMe3, Me, Ph, CHMe2, CH2Cl), which were synthesized by the reaction of Pd(NO)Cl with silver carboxylates Ag(OCOR). X-ray crystal structure of Pd4(µ-NO)2(µ-OCOCMe3)6 was determined [176]. The four Pd atoms form an almost rectangular Pd4 skeleton with the pair of bridging ligands on each side of the rectangle. The same group also reported a tetranuclear complex Pd4(NO)4(CF3COO)4 which was generated from the reaction of tetranuclear carbonyl complex Pd4(CO)4(CF3COO)4 with NO. Another tetranuclear Pd4(µ-NO)2(µ-CF3CO2)4(η2-CH2=CHPh)4 complex was also isolated, that has a tetrahedral core, with η2-coordinated styrene molecules and half-bridging nitrosyl and carboxylate groups [177]. The direct reaction of Pd3(µ-RCO2)6 (R = CH3, CMe3) with NO gives corresponding nitrosyl complexes Pd4(µ-NO)2(µ-RCO2)6.

5. Pentanuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

5.1. Linked by Sulfur

Only a few pentametallic nitrosyl compounds have been synthesized. Darensbourg and co-workers synthesized a trigonal paddlewheel with iron-dithiolato ligand paddles, {[(bme-dach)Fe(NO)]3Ag2}[BF4]2, which was prepared by the reaction of AgBF4 with (bme-dach)Fe(NO) [178]. The EPR and magnetic studies showed the complex is paramagnetic (g = 2.024) with three {Fe(NO)}7 units. The same group also reported a heteropentametallic complex Ni2(N2S2)2[Fe(NO)2]3, (N2S2 = bme-dach), in which the two nickels and three irons are linked by triply bridging thiolate sulfurs in a cluster of core composition Ni2S4Fe3. It was prepared through the reaction of Ni(N2S2) with an excess of Fe(CO)2(NO)2 [135] The reactivity property of the pentametallic complex towards CO was investigated and revealed that the cluster converts back to Ni(N2S2)Fe(NO)2(CO).

Stasicka’s group reported that RRS is inert in an alkaline medium, but can readily transform into the various polynuclear clusters such as [Fe4(µ3-S)3(NO)7]−, [Fe5(µ3-S)4(NO)8]−, and [Fe7(µ3-S)6(NO)10]− via the proposed protonated intermediate [Fe2(µ2-SH)2(NO)4] under acidic conditions [179].

5.2. Linked by N/O

Shishilov et al. reported that the reaction of Pd4(µ-NO)2(µ-RCO2)6 (R = CMe3, cyclo-C6H11) complexes with acetonitrile in acetone led to the formation of complexes Pd5(µ-NO)(µ-NO2)(µ-CMe3CO2)6(CH3C(=N)OC(=N)CH3) and Pd5(µ-NO)(µ- C6H11CO2)7(CH3C(=N)OC(=N)CH3) [180]. They represent palladium carboxylate clusters containing a 5-nuclear cyclic metal core, as established by X-ray diffraction analysis. Three Pd atoms coordinate the acetimidic anhydride ligand. The main structural features of the two complexes are similar.

6. Hexanuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

6.1. Bridged by Sulfur

Coucouvanis reported two methods of synthesizing of (PPN)2[Fe6S6(NO)6)]. Both of them are complicated multistep procedures through other iron-sulfur-nitrosyl clusters: one by refluxing (PPN)[Fe4S3(NO)7], (PPN)2[Fe4(CO)13] and Bz2S3 in MeCN for 24 h; and another by mixing (PPN)2[Fe8S6(NO)8] with Bz2S3 in DMF at room temperature for 24 h [170].

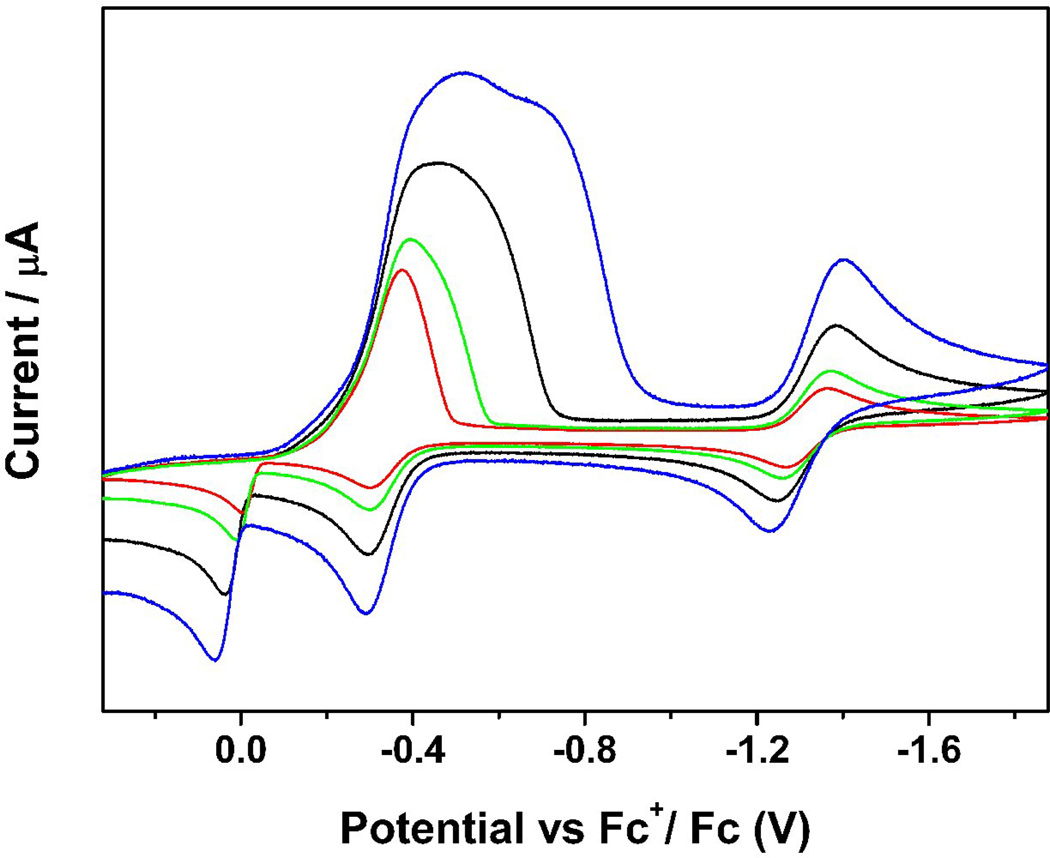

Recently we also reported a hexanuclear iron-sulfur nitrosyl cluster, [(n-Bu)4N]2[Fe6S6(NO)6], 44, which was synthesized using simpler solvent-thermal reactions by mixing [(n-Bu)4N][Fe(CO)3NO], sulfur, and methanol in a vial under a nitrogen atmosphere and heated to 120°C for 48 hours in an autoclave, and was subsequently allowed to cool to room temperature [161]. The IR spectrum displayed one strong characteristic NO stretching frequency at 1698 cm−1 (νNO) in solution with the characteristic of NO+. The redox behavior was also studied by CV and showed two cathodic current peaks at Epc = −0.30 and −1.29 V and three anodic peaks at Epa = 0.08, −0.23 and −1.19 V, where the first reduction peak is much stronger than the second one. The cyclic voltammograms were also recorded using various scan rates from 0.1 V/S to 1.0 V/S (Figure 10). When faster scan rates were applied, the first reduction peak was separated to two reductions. Meanwhile, the faster the scan rate, the clearer the separation observed between the two reduction peaks. The intensity of the unusually strong peak is a result of mixed redox processes. One is the quasi-reversible reduction and the other is from an irreversible electrochemical process, in which the compound goes through a typical electron transfer and chemical reaction (ECE) mechanism creating a product that is easier to reduce (less negative value) than the original one, which results in an overlap of the reduction potentials.

Figure 10.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 1mM solution of [(n-Bu)4N]2[Fe6S6(NO)6] in 0.1 M (NBu4)(PF6) / CH3CN at scan rate of 0.10 (red), 0.20 (green), 0.50 (black) and 1.00 (blue) V/S. Reprinted with permission from [161]. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

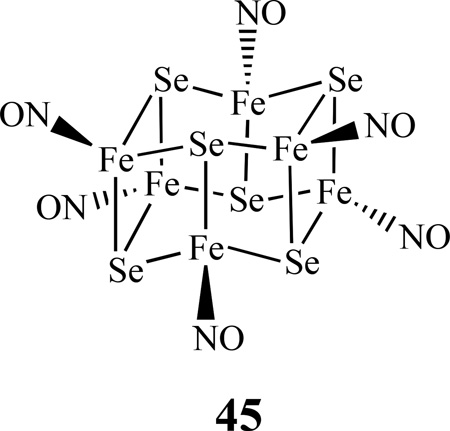

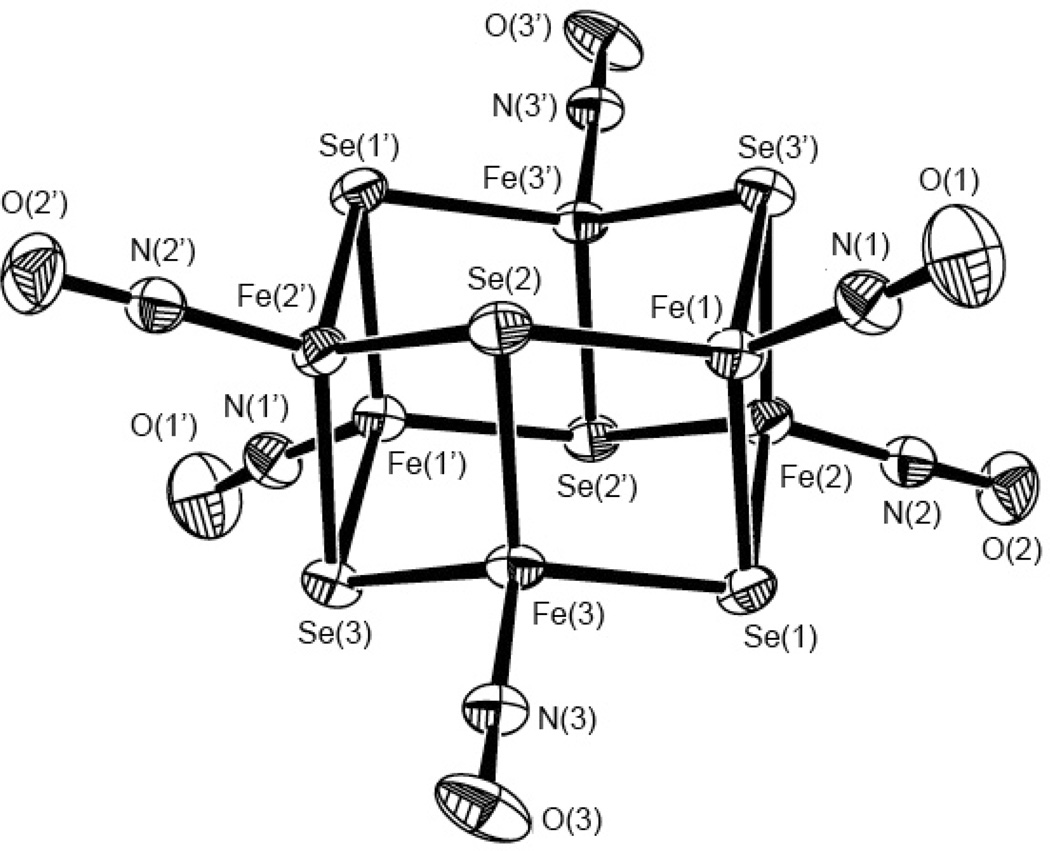

6.2. Bridged by Se

Despite many known examples of iron-sulfur nitrosyl clusters, iron-selenium nitrosyl clusters are extremely rare. Recently, we were able to isolate a new class of iron-selenium nitrosyl cluster with a formula of [(n-Bu)4N]2[Fe6Se6(NO)6], 45. Complex 45 was prepared by the solvent-thermal reactions of one equivalent of [(n-Bu)4N][Fe(CO)3NO] and four equivalents of selenium in methanol in a sealed vial under a nitrogen atmosphere and heated to 120°C for 48 hours in an autoclave, during which the formation of the product was monitored by FT-IR spectroscopy [161].

The IR spectrum displayed one strong characteristic NO stretching frequency at 1694 cm−1 (νNO) in solution with the characteristic of NO+. The X-ray crystallographic study showed two parallel “chair-shape” structures, consisting of three iron and three selenium atoms, and are connected by Fe-Se (Figure 11). Each iron center is bonded to three selenium atoms and a nitrogen atom from the nitrosyl ligand with pseudo tetrahedral center geometry. There is a fairly strong interaction between the two iron centers as reflected by the relatively short average Fe-Fe distance of 2.730 Å.

Figure 11.

The X-ray crystal structure of [Fe6Se6(NO)6]2− with thermal ellipsoids drawn at 50% probability. Reprinted with permission from [161]. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

The electrochemistry of complex 45 was studied by cyclic voltammetry (Figure 12). Complex 45 showed two cathodic current peaks at Epc = −0.42 (unusually strong) and −1.36 V and three anodic peaks at Epa = −0.04, −0.38 and −1.30 V. Detailed electrochemical studies such as scanning CV with different potential ranges showed that the oxidation peak at −0.04 V is the product of the reduction at −0.42 V. The intensity of the unusually strong peak at Epc = −0.42 V is a result of at least three processes. One is the quasi-reversible reduction at E1/2° = −0.41 V and the other two are from an irreversible electrochemical process that occurred at Epc = −0.42 V, in which the compound went through a typical electron transfer and chemical reaction (ECE) mechanism of which its product reduces easier (less negative value) than the original one, resulting in an overlap of the reduction potentials and subsequently, a very strong peak. The peak at Epa = −0.04 V is the product from such a chemical reaction.

Figure 12.

Cyclic voltammograms of a 1mM solution of [(n-Bu)4N]2[Fe6Se6(NO)6] in 0.1 M (NBu4)(PF6) / CH3CN at scan rate of 100 mV/S. Reprinted with permission from [161]. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

6.3. Linked by N/O/C

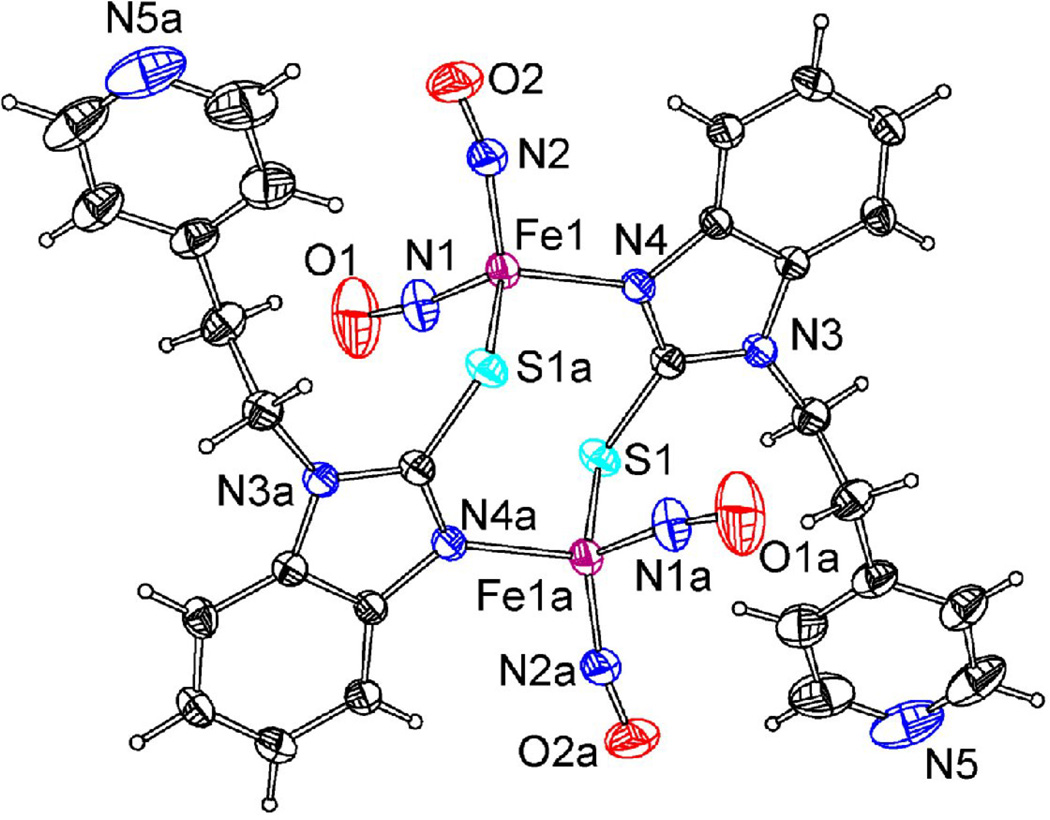

Lehnert obtained a metallacrown hexamer complex, [Fe(BMPA-Pr)(NO)]6[ClO4], 46, (BMPA-Pr = N-propanoate-N, N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine) [181]. The carboxylate group of each unit bridges two adjacent iron centers, giving ring structures wherein all six NO moieties point toward the center of the ring as shown in Figure 13. EPR spectra of the hexameric complexes showed evidence of weak electronic coupling between the {Fe(BMPA-Pr)-(NO)} units indicating that these hexamers remain intact in solution.

Figure 13.

Crystal structures of [Fe(BMPA-Pr)(NO)]Cl and a metallacrown hexamer complex, [[Fe(BMPA-Pr)(NO)]6[ClO4]. All of the solvent molecules and H atoms have been omitted for clarity. Reprinted with permission from [181]. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

7. Octanuclear Metal Nitrosyl Complexes

7.1. Linked by Sulfur

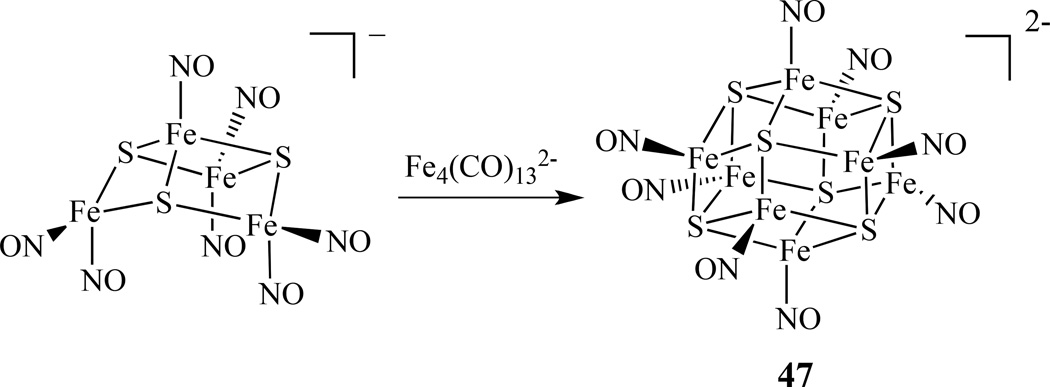

The synthesis of octanuclear iron-sulfur nitrosyl clusters were explored by Coucouvanis’ group. (PPN)2[Fe8S6(NO)8], [PPN = bis(triphenylphospine)iminium] was obtained from the reaction of (NH4)[Fe4S3(NO)7] with (PPN)2[Fe4(CO)13] in high yield (Scheme 26) [182]. It was proposed that the reaction might proceed through the abstraction of nitrosyls from [Fe4S3(NO)7]− by the [Fe4(CO)13]2− cluster and the possible formation of an [Fe4S3(NO)4]− intermediate, which subsequently self-coupled to form the [Fe8S6(NO)8]2− cluster, 47. The two-electron-reduced cluster [Fe8S6(NO)8]4− was isolated as both PPN+ and K+ salts upon reduction of the cluster using an excess of potassium anthracenide. The potassium salt was characterized by X-ray crystallography and identified as a K4(DMF)13[Fe8S6(NO)8] cluster.

Scheme 26.

Synthesis of octanuclear iron-sulfur nitrosyl cluster of [Fe8S6(NO)8]2− 47 [182].

Several octanuclear nitrosyl complexes with mixed metals were prepared by using (PPN)2[Fe6S6(NO)6] as a precursor molecule. For instance, (PPN)2[(CO)6Mo2Fe6(NO)6], was obtained from mixing a [Fe6S6(NO)6] cluster with Mo(CO)3(MeCN)3 at room temperature, and (PPr3)2Cu2Fe6S6(NO)6, was obtained by mixing the [Fe6S6(NO)6] cluster with [Cu(MeCN)4]PF6, and tripropyl phosphine (PPr3). A similar reaction using the cluster with [Ni(MeCN)6](BF4)2 and PPr3 resulted in two products: (PPr3)2Ni2Fe6S6(NO)6, and (PPr3)3Ni3Fe4S6(NO)4 [170].

7.2 Linked by N/O/C

Shishilov and co-workers reported that the reaction of the palladium carbonyl carboxylate Pd6(µ-CO)6(µ-RCO2)6 (R = Pr, i-Bu, t-Bu) with gaseous nitrogen monoxide generated two octanuclear complexes: Pd8(µ-NO2)4(µ-CO)2(µ-NO)2(µ-RCO2)8 and Pd8(µ-NO2)4(µ-NO)4(µ-RCO2)8 [183–184].

8. Conclusions

The extraordinarily significant roles that nitric oxide plays in biological systems have brought a renewed interest in the coordination chemistry of metal nitrosyls, as many of these compounds also exhibit biological activities ranging from releasing, storing, and transporting nitric oxide, to acting as a cytotoxic agent towards cancerous cells. This review illustrates a broad overview of advances in the synthesis, spectroscopic properties, and reactivity of multinuclear metal nitrosyl complexes, including Roussin’s salts and ester derivatives, over the last decade. The examples cited in this review show the tremendous effort that is still being applied to the preparation and understanding of new transition metal nitrosyl complexes. A variety of methods in preparing these systems have been surveyed. A majority of the complexes have been investigated by common characterization methods such as IR, UV-vis, EPR, NMR, X-ray crystallography, Mössbauer, SQUID, CV, DFT calculations, etc. Less common techniques such as X-ray absorption spectroscopy, Resonance Raman, and NRVS have also been applied to study these systems recently. A very good understanding on the systems has been achieved. The next step would be to connect the understanding on structures and properties with biological activities and applications so that the full potential of these complexes can be unlocked.

Highlights.

The extraordinary significant roles that nitric oxide plays in biological systems have brought a renewed interest in the coordination chemistry of metal nitrosyls, as many of these compounds also exhibit biological activities ranging from releasing, storing, and transporting nitric oxide, to acting as a cytotoxic agent towards cancerous cells. This review illustrates a broad overview of advances in the synthesis, spectroscopic properties, and reactivity of multinuclear metal nitrosyl complexes, including Roussin’s salts and ester derivatives, over the last decade.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the National Institute of Health (NIH) MBRS SCORE Program (2SC3GM092301-05) for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Culotta E, Koshland DE. Science. 1992;258:1862–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1361684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancaster JR, Jr, Hibbs JB., Jr Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:1223–1227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman PL, Griffith OW, Stuehr DJ. Chem. Eng. News. 1993;71:26–38. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruckdorfer R. Mol. Aspects Med. 2005;26:3–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attia AA, Makarov SV, Vanin AF, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2014;418:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwon YM, Weiss B. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:5369–5376. doi: 10.1128/JB.00586-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss B. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:829–833. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.3.829-833.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tennyson AG, Lippard SJ. Chem. & Biol. 2011;18:1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter-Addo GB, Legzdins P. “Metal Nitrosyls”. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ignarro LJ. Nitric Oxide: Biology and Pathobiology. 2nd ed. Burlington: Elsevier Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bredt DS, Hwang PM, Glatt CE, Lowenstein C, Reed RR, Snyder SH. Nature. 1991;351:714–718. doi: 10.1038/351714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo J, Campbell SL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2314–2322. doi: 10.1021/bi035275g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moncada S, Palmer RMJ, Higgs EA. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke MJ, Gaul JB. Structure and Bonding. 1993;81:147–181. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wodd KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1987;84:9265–9269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denninger JW, Marletta MA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1411:334–350. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welter R, Yu L, Yu CA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;331:9. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster MW, Cowan JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4093–4100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer RMJ, Ferrige AG, Moncada S. Nature. 1987;327:524–526. doi: 10.1038/327524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidalgo E, Bollinger JM, Bradley TM, Walsh CT, Demple B. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20908–20914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Mel A, Murad F, Seifalian AM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5742–5767. doi: 10.1021/cr200008n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller B, Kleschyov AL, Stoclet JC. Brit J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1281–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanin FA, Serezhenkov VA, Mikoyan VD, Genkin MV. Nitric Oxide. 1998;2:224–234. doi: 10.1006/niox.1998.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding H, Demple B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5146–5150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler AR, Megson IL. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1155–1165. doi: 10.1021/cr000076d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szaciłowski K, Chmura A, Stasicka Z. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005;249:2408–2436. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonzetich ZJ, McQuade LE, Lippard SJ. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6338–6348. doi: 10.1021/ic9022757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanin AF. Nitric Oxide. 2009;21:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodrich LE, Paulat F, Praneeth VKK, Lehnert N. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6293–6316. doi: 10.1021/ic902304a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wasser IM, de Vries S, Moënne-Loccoz P, Schröder I, Karlin KD. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1201–1234. doi: 10.1021/cr0006627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang PG, Xian M, Tang X, Wu X, Wen Z, Cai T, Janczuk AJ. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:1091–1134. doi: 10.1021/cr000040l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford PC, Lorkovic IM. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:993–1018. doi: 10.1021/cr0000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coppens P, Novozhilova I, Kovalevsky A. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:861–884. doi: 10.1021/cr000031c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews L, Citra A. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:885–912. doi: 10.1021/cr0000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mingos DMP. Struct. Bond. 2014;154:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright AM, Hayton TW. Comm. Inorg. Chem. 2012;33:207–248. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berto TC, Speelman AL, Zheng S, Lehnert N. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:244–259. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ford PC, Pereira JCM, Miranda KM. Struct. Bond. 2014;154:99–136. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cruza CD, Sheppard N. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2011;78:7–28. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewandowska H. Struct. Bond. 2013;153:45–114. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lehnert N, Scheidt WR, Wolf MW. Struct Bond. 2014;154:155–224. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salmon DJ, Tolman WB. Struct. Bond. 2014;154:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roussin J. Ann Chim Phys. 1858;52:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffmann KA, Wiede OFZ. Anorg. Chem. 1895;9:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chau CN, Wojcicki A. Polyhedron. 1992;11:851–852. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crayston JA, Glidewell C, Lambert RJ. Polyhedron. 1990;9:1741–1746. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy D, Lancaster JR, Jr, Cornforth DP. Science. 1983;221:769–770. doi: 10.1126/science.6308761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yukl ET, Elbaz MA, Nakano MM, Moënne-Loccoz P. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13084–13092. doi: 10.1021/bi801342x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tinberg CE, Tonzetich ZJ, Wang H, Do LH, Yoda Y, Cramer SP, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:18168–18176. doi: 10.1021/ja106290p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harrop TC, Tonzetich ZJ, Reisner E, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15602–15610. doi: 10.1021/ja8054996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crack JC, Green J, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:3196–3205. doi: 10.1021/ar5002507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren B, Zhang N, Yang J, Ding H. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70:953–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maraj SR, Khan S, Cui XY, Cammack R, Joannou CL, Hughes MN. Analyst. 1995;120:699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cui XY, Joannou CL, Hughes MN, Cammack R. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1992;98:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanin AF. Open Conf. Proc. J. 2013;4:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Landry AP, Duan X, Huang H, Ding H. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 2011;50:1582–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rauchfuss TB, Weatherill TD. Inorg. Chem. 1982;21:827–830. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harrop TC, Song D, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3528–3529. doi: 10.1021/ja060186n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang R, Camacho-Fernandez MA, Xu W, Zhang J, Li L. Dalton Trans. 2009:777–786. doi: 10.1039/b810230a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin ZS, Lo FC, Li CH, Chen CH, Huang WN, Hsu IJ, Lee JF, Horng JC, Liaw WF. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:10417–10431. doi: 10.1021/ic201529e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dillinger SA, Schmalle HW, Fox T, Berke H. Dalton Trans. 2007:3562–3571. doi: 10.1039/b702461d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vanin AF, Poltorakov AP, Mikoyan VD, Kubrina LN, Burbaev DS. Nitic Oxide-Biol. Ch. 2010;23:136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.05.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Broillet MC. S-Nitrosylation of proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999;55:1036–1042. doi: 10.1007/s000180050354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grabarczyk DB, Ash PA, Vincent KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11236–11239. doi: 10.1021/ja505291j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Conrado CL, Bourassa JL, Egler C, Wecksler S, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:2288–2293. doi: 10.1021/ic020309e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conrado CL, Wecksler S, Egler C, Magde D, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:5543–5549. doi: 10.1021/ic049459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wecksler SR, Mikhailovsky A, Ford PC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13566–13567. doi: 10.1021/ja045710+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wecksler SR, Hutchinson J, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:1192–1200. doi: 10.1021/ic051723s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wecksler SR, Mikhailovsky A, Korystov D, Ford PC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3831–3837. doi: 10.1021/ja057977u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wecksler SR, Mikhailovsky A, Korystov D, Buller F, Kannan R, Tan LS, Ford PC. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:395–402. doi: 10.1021/ic0607336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ford PC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:190–200. doi: 10.1021/ar700128y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang HH, Huang HJ, Ho YL, Wen YD, Huang WN, Chiou SJ. Dalton Trans. 2009:6396–6402. doi: 10.1039/b902478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, Morton JR, Preston KF. Mag. Reson. Chem. 1995;31:s14–s19. [Google Scholar]