Abstract

Thymidylate synthase (TSase) is a clinically important enzyme because it catalyzes synthesis of the sole de novo source of deoxy-thymidylate. Without this enzyme, cells die a “thymineless death” since they are starved of a crucial DNA synthesis precursor. As a drug target, TSase is well studied in terms of its structure and reaction mechanism. An interesting mechanistic feature of dimeric TSase is that it is “half-the-sites reactive”, which is a form of negative cooperativity. Yet, the basis for this is not well-understood. Some experiments point to cooperativity at the binding steps of the reaction cycle as being responsible for the phenome non but the literature contains conflicting reports. Here we Contrary to these reports are the x-ray models of TSase, which for the case of the E. coli enzyme, have yet to capture detailed thermodynamic dissection of multi-site binding of dUMP to E. coli TSase shows the nucleotide binds to the free and singly bound forms of the enzyme with nearly equal affinity over a broad range of temperatures and in multiple buffers. While small but significant differences in ΔC°P for the two binding events show that the active sites are not formally equivalent, there is little-to-no allostery at the level of ΔG°bind. In addition NMR titration data reveal that there is minor inter-subunit cooperativity in formation of a ternary complex with the mechanism based inhibitor, 5F-dUMP, and cofactor. Taken together, the data show that functional communication between subunits is minimal for both binding steps of the reaction coordinate.

Thymidylate synthase (TSase) catalyzes the synthesis of the sole source of dTMP in organisms ranging from viruses to humans1. The mechanism involves reductive methylation of the substrate, dUMP, using a cofactor, N5,N10-methylene- 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate (CH2H4fol), as both a methylene and hydride donor2. Given its key role in DNA synthesis and cell division, TSase is an attractive drug target for treating microbial infection and cancer. As such, it is highly scrutinized in terms of its structure and catalytic mechanism. TSase is a dimeric enzyme with two active sites and one often cited feature is that there is allostery between the two sites, which are separated by ~30 Å. Among these reports are that TSase is a half-the-sites reactive enzyme3,4, the enzyme binds to only a single mole-cule of substrate5, or binds it with negative cooperativity6, and the enzyme binds to only a single mole-cule of cofactor 7,8, or binds it with negative cooperativity9. Contrary to these reports are the X-ray models of TSase, which for the case of the E. coli enzyme, have yet to capture singly bound forms. Rather, structures show symmetrical subunits with full occupancy of both active sites. These data, coupled with an NMR spectrum of substrate analog and co-factor-saturated TSase clearly showing binding to both sub-units10, are inconsistent with extreme negative cooperativity. However, the question of cooperativity remains open because there has yet to be a rigorous study of the binding events in this key enzyme. To settle this, we measured the thermodynamics of binding of substrate and cofactor to both sites of E. coli TSase. We employed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), which is exquisitely sensitive to strength, heat, and stoichiometry of binding, to provide the first detailed thermodynamic picture of the TSase-dUMP interaction. We show that E. coli TSase binds two molecules of dUMP, and unexpectedly, that both the free and singly bound forms have the same affinity for substrate. Further, our analysis highlights the challenges with analyzing multisite binding data in that very small errors in ITC cell concentration can lead to dramatically different pictures of cooperativity. Only by measuring titrations at multiple conditions and by including cell concentration as a fitted parameter were we able to obtain accurate binding parameters. For the case of cofactor binding, where heat of covalent bond formation can complicate interpretation of ITC data, we used NMR spectroscopy to directly quantify populations of all states over the course of a titration with a substrate analog and cofactor. This is a powerful approach as it provides a rare11,12 opportunity to monitor microscopic states in a multi-binding site system. The data show both sites are similar with respect to formation of the ternary complex, demonstrating that allostery is minimal for the two binding steps of the reaction cycle.

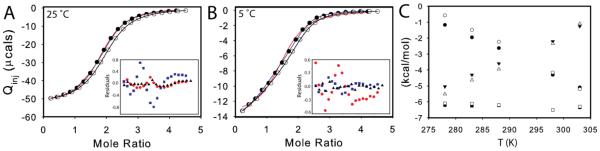

Given the general interest in the phenomenon of allostery and the question of dUMP binding in TSase, we set out to probe the binding thermodynamics of this dimeric system. Thermodynamics of substrate binding was measured by ITC at 25 °C (Figure 1, Figure S3). The data fit well to a single site model with a stoichiometry (n) of 1.8 (Figure 1A, Table S1), but based on reports of cooperativity in this5 and other forms6 of the enzyme, the data were also fit to a general model that can accommodate differences in affinities and heats between the two binding events. The general model fit t0 intrinsic KD,1 of ~4μM and KD,2 of ~ 20 μM, for a ρ-value (Ratio of KA2/KA1) of 0.21 (Figure 1A, Table S1). This suggests negative cooperativity, but a comparison of reduced χ2 indicates the single model is a better fit to the data (Figure 1A, (χ2 values for all models are compared in Table S1). Even though the single sites model gives the superior fit, both models make assumptions that might not be accurate for this system. The main assumption with the single sites model is that each of the n sites has the same K and ΔH° and it could be the case that K1≠K2 and/or ΔH°1≠ΔH°2. The potential pit-fall of the general model is that all of the calculated and fitted parameters are dependent on a fixed n (n=2 in the case of TSase). The fact that the best fitting single site model gave a non-integral stoichiometry of 1.8 raised the possibility that errors in ITC cell concentration, which are not taken into account by the general multi-site model within the Origin ITC package, could lead to erroneous fits.

Figure 1.

ITC measurement of dUMP binding to TSase. Conditions are 290 uM TSase in the cell and 6 mM dUMP in the syringe, both in 25 mM NaPO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. (A, B) Fits are shown for dUMP titrations using models for one-site binding (red line against closed circles), general two-site binding (blue line against closed circles), and modified general binding (black lines against open circles); insets show residuals for one-site binding (red circles), general two-site binding (blue squares), and modified general binding (black triangles). For both 25 °C (A) and 5 °C (B), original data points are shown as filled circles, and data points corrected for cell concentration are shown as open circles. C) The modified general model was used to fit ITC data at multiple temperatures. The thermodynamic parameters, ΔH (circles), -TΔS (triangles) and ΔG (squares), for binding to free (black) and singly bound (white) TSase are shown as functions of temperature. The slope of ΔH versus T yields ΔCp=-157 cal/molK and ΔCp=-183 cal/molK for binding to free and singly bound TSase, respectively. Errors in parameters were determined from Monte Carlo simulations and the error bars are smaller than the points. Values for fitted parameters from the modified general model are shown in Table S2.

To overcome these issues, the data were fit using a general binding model that included cell concentration as a fitted parameter (See Supporting Information). Treating protein concentration as an adjustable parameter is reasonable given the possibility that the active fraction of TSase is less than 100%, and potential discrepancy between actual and theoretical extinction coefficients. Further, fitting protein concentration within the general model was employed previously with other multi-binding site systems13,14. This is a rigorous fitting approach because the only assumption is the total number of binding sites. The assumption is justified here by the x-ray model of the E. coli TSase-dUMP complex in which both sites have full occupancy15. Fits to this modified general model (Figure 1A) gives ρ≈1, a lower reduced χ2 than either the single or unmodified general models (Table S1), and a fitted protein concentration 10% lower than that measured by UV spectroscopy. To ensure that the improved χ2 associated with the modified general model is not simply the result of over-fitting, we doubled the ratio of observables to fitted parameters by performing global fits to paired titrations with either two cell or syringe concentrations. This approach was shown previously to break degeneracies and increase robust-ness of fitted ITC parameters16. Global fits to the paired titrations described above yield ρ≈1 (Figure S3, Table S1) in support of using the modified general model and the conclusion that binding affinities are similar. This analysis underscores the importance of accounting for inaccuracies in ITC cell concentration as errors of even 10% here can lead to a misinterpretation of up to 5-fold negative cooperativity when binding sites are truly identical (Table S1).

Because the heat capacity change upon binding is a sensitive probe of changes in structure and dynamics upon binding17, we looked at dUMP binding at additional temperatures. The data fit poorly to the single site model at some temperatures other than 25 °C (Figure 1B, Figure S4, Table S1), indicating that either cooperativity is temperature dependent, or that ΔH°1 and ΔH°2 are not equivalent at all temperatures. The data were then fit to the modified general model which, for cases where ΔH°1 ≠ ΔH°2, fits significantly better than either the single or un-modified general models (Figure 1B, Table S1, Figure S4). Data for all five temperatures showed both types of active site have nearly equivalent binding affinity (Figure 1C, Tables S1&2) and all datasets required a similar correction to enzyme concentration, which is expected if the enzyme originates from the same preparation. In contrast to binding affinities, ΔH° for the two binding events diverge as a function of temperature (Figure 1C and Table S2). The temperature trends highlight the difficulty with fitting all of the data to the single sites model because both sites are not described by the same set of ΔH° parameters (Table S2). The slope of ΔH° versus T yields a ΔC°P of 157 ± 1 cal/mol•K for site 1 and 183 ± 2 cal/mol•K for site 2 (Figure 1C). Overall, the apo and singly bound forms of TSase bind dUMP with similar affinities, but the sites are not equivalent based on small but significant differences in ΔC°P.

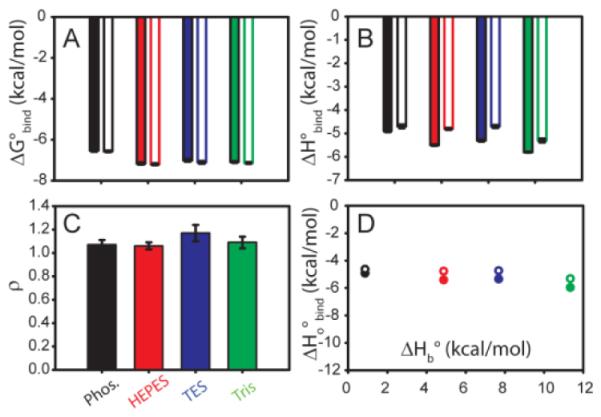

To determine if the differences in ΔH° were the result of proton exchange with the solution upon dUMP binding, titrations were conducted in a series of four buffers with different heats of buffer ionization, ΔHb. The chosen buffers were phosphate, HEPES, TES, and Tris in order of increasing ΔHb 18 The measured ΔH° from ITC is linked to the of heat ionization of the buffer (ΔH°b) and is related to the number of protons exchanged during binding19. The data were fit to the general binding model with adjustable protein concentration, and fit with ρ ≈ 1 for all buffers (Figure 2, Figure S5, Table S3), a convergence which further supports this fitting model. Binding is two to three fold weaker in phosphate than in the other buffers (Table S3). The difference in binding affinity may be attributable to preferential interaction with phosphate as the ion alone is shown to bind TSase at the same site as the phosphate moiety of dUMP15. Thus phosphate may be a better competitor for dUMP binding than the other buffers used here. The slopes of ΔH° versus ΔH°b (Figure 2D) indicate that less than 0.1 mol of H+ are taken up by the protein upon dUMP binding and H+ linkage does not play a large role in dUMP binding.

Figure 2.

Minimal proton linkage accompanies dUMP binding to TSase. Modified general model was used to fit ITC experiments in multiple buffers with different enthalpies of ionization (ΔH° b). Buffer color key in (C) applies to all panels. In panels A, B, and D, sites 1 (2) are represented by filled (open) bars/symbols. Slopes of lines in panel D give number of protons (n) linked to binding. Site 1 (•) fits to n of −0.09 ± 0.02 protons and ΔHiof −4.8 ± 0.17 kcal/mol. Site 2 (∘) fits to n of −0.06 ± 0.03 protons and ΔHiof −4.5 ± 0.19 kcal/mol. Example fits are given in Figure S5, with values in Table S3.

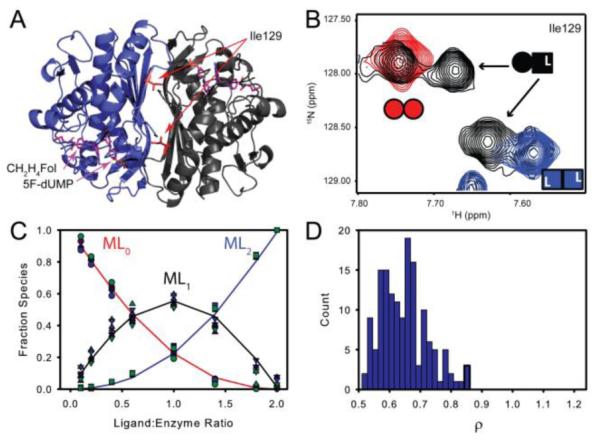

It is possible that cooperative effects alternatively reside at the cofactor binding step. Substrate binding results in only modest conformational changes in TSase20. Addition of cofactor or cofactor analog causes more dramatic rearrangements in the local binding site20 that could influence the neighboring subunit. This, coupled with reports of cofactor analog binding cooperativity in human9 and bacterial TSase7,8 prompted us to further investigate cofactor binding. We chose to monitor binding of the substrate analog, 5F-dUMP, ΔHb and the biological cofactor, CH2H4Fol by NMR titration. In the resulting ternary complex, C146 makes a covalent bond to 5F-dUMP, which is covalently attached via a methylene bridge to the cofactor21; the covalent attachments make it such that the two small molecules can be treated as a single “di-ligand”. Importantly, the di-ligand is considered a mech-anism-based inhibitor as these covalent bonds are formed during the normal reaction cycle2. Therefore, the complex is an excellent model for cooperativity in ternary complex formation during catalysis. Further, structures of this complex are isosteric with other complexes involving dUMP and cofactor analogs22,23. Lastly, the stability of the complex yields high quality NMR spectra with resonances that are in slow-exchange on the NMR timescale, facilitating the quantification of all species (see below).

Titrations of TSase with the di-ligand were monitored by TROSY-1H-15H HSQC spectra. A subset of residues at the dimer interface yielded two resonances corresponding to the singly bound state that are distinct from symmetrical free and doubly bound resonances (Figure 3A&B). This allowed us to directly measure the fraction of free, singly bound, and doubly bound microstates12. Four amides give well resolved peaks for all three states; intensities from these residues were fit to the two-site binding polynomial (see Supporting Information). At the limit of stoichiometric binding, which is observed in this case, we cannot determine the absolute binding affinities. However, differences in the relative binding affinities between the two sites are readily apparent (Figure S6). In the case of di-ligand binding to TSase, the ρ-values range from 0.55 to 0.90 for fits of single residue data (Figure S7 and Table 1). A global fit of all four residues yielded a ρ of 0.65 ± 0.075 (Figure 3C&D and Table 1), which indicates a slight degree of negative cooperativity with a maximum magnitude of less than two-fold.

Figure 3.

Both TS active sites have similar affinity for the 5F-dUMP-CH2H4Fol “di-ligand”. A&B) In NMR spectra, at intermediate titration points (black, (B)), resonances from a subset of residues near the dimer interface (e.g. Ile 129 in (A)) have chemical shifts from the singly bound state that are different from the free (red, Panel (B)) and doubly bound states (blue (B)). For these residues there are four resonances total at intermediate titration points as the singly bound state produces two peaks: one from the free subunit and one from the bound subunit (B). C) Global fit of peak intensities from the four resonances having all three states resolved in NMR spectra. Circles and squares represent free and doubly bound data, respectively. Upward triangles are from the free subunit of singly bound species and downward tringles are from the bound subunit. D) Histogram of ρ (K2/K1 ratio) from fits of 150 Monte Carlo simulated datasets.

Table 1.

Relative binding constants for TSase 5F-dUMP-CH2H4Fol di-ligand binding from NMR titration.

| Residue | ρ a |

|---|---|

| Gln33 | 0.88 ± 0.067 |

| Ile129 | 0.90 ± 0.12 |

| Asn134 | 0.57 ± 0.080 |

| Unassigned Trp Indole | 0.77 ± 0.14 |

|

| |

| Global fit | 0.65 ± 0.075 |

Ratio of intrinsic association constants (K2/K1)

The data presented herein unequivocally show that substrate binds to the free and singly bound forms of E. coli TSase with similar affinity. This finding contrasts with a previous fluorescence study showing only one molecule of dUMP bound per TSase dimer5. It is unlikely that solution conditions account for the discrepancy as we observe equivalent binding affinity at multiple temperatures and in all buffers tested. It is more probable that the fluorescence results were confounded by complex interactions between the seven tryptophan probes per TSase subunit. These issues are circumvented by the direct link between binding and heat of reaction measured by ITC. It is noteworthy that while dUMP binding affinities are the same in both the free and singly bound enzyme, ΔH°1 and ΔH°2 are not equivalent at some temperatures and in some buffers. This phenomenon, in which binding is similar at the level of ΔG°, but different based on ΔH° and TΔS°, was termed “silent allosteric coupling”24. The recent linkage between binding and redistribution of side-chain dynamics25-28 and the connection between side-chain dynamics and conformational entropy26,29,30 suggests this type of coupling is wide-spread.

We also show by NMR, that the ternary complex is formed with nearly equal probability in both subunits which disagrees with an ITC study showing roughly one molecule binds to dimeric E. coli TSase7. It is difficult to compare our data with the published ITC study because the fitting models are not described in detail and our work provides a dramatic example of how choice of fitting model can affect interpretation of ITC in multi-binding site systems. However, our data are in agreement with crystal structures15,21,23,31 and NMR spectra10 that show two molecules of cofactor are bound. Interestingly, binding the first di-ligand does elicit chemical shift changes in the empty subunit (Figure 3B) leading us to conclude that the effects of binding are communicated across the dimer interface. We are currently investigating this coupling. Lastly, we should emphasize that our work does not necessarily reflect on reports that eukaryotic TSase is a cooperative enzyme because, unlike the enzyme studied here, symmetry is broken in forms from higher organisms by an active site appendage that adopts multiple conformations in the absence of ligands32,33.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by GM083059 (A.L.L.) and GM065368 (Amnon Kohen). We would like to thank Prof. Amnon Kohen for helpful discussions and Ashutosh Tripathy, Ph.D. for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Detailed experimental procedures including ITC and NMR titration fitting methods, additional ITC curves, NMR spectra, and local fits to NMR titrations.

“This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Perry KM, Fauman EB, Finer-Moore JS, Montfort WR, Maley GF, Maley F, Stroud RM. Proteins. 1990;8:315. doi: 10.1002/prot.340080406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Carreras CW, Santi DV. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:721. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Johnson EF, Hinz W, Atreya CE, Maley F, Anderson KS. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:43126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Maley F, Pedersen-Lane J, Changchien L. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1469. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Spencer HT, Villafranca JE, Appleman JR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4212. doi: 10.1021/bi961794q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Reilly RT, Barbour KW, Dunlap RB, Berger FG. Molecular pharmacology. 1995;48:72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Arvizu-Flores AA, Sugich-Miranda R, Arreola R, Garcia-Orozco KD, Velazquez-Contreras EF, Montfort WR, Maley F, Sotelo-Mundo RR. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2008;40:2206. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Anderson AC, O'Neil RH, DeLano WL, Stroud RM. Bio-chemistry. 1999;38:13829. doi: 10.1021/bi991610i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Dev IK, Dallas WS, Ferone R, Hanlon M, McKee DD, Yates BB. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:1873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sapienza PJ, Lee AL. Biomolecular NMR assignments. 2014;8:195. doi: 10.1007/s12104-013-9482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Freire E, Schon A, Velazquez-Campoy A. Methods Enzymol. 2009;455:127. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tochtrop GP, Richter K, Tang C, Toner JJ, Covey DF, Cistola DP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012379199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sahun-Roncero M, Rubio-Ruiz B, Saladino G, Conejo-Garcia A, Espinosa A, Velazquez-Campoy A, Gervasio FL, Entrena A, Hurtado-Guerrero R. Angewandte Chemie. 2013;52:4582. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jobichen C, Fernandis AZ, Velazquez-Campoy A, Leung KY, Mok YK, Wenk MR, Sivaraman J. The Biochemical journal. 2009;420:191. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Stout TJ, Sage CR, Stroud RM. Structure. 1998;6:839. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Freiburger LA, Auclair K, Mittermaier AK. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2009;10:2871. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Prabhu NV, Sharp KA. Annual review of physical chemistry. 2005;56:521. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Goldberg RN, Kishore N, Lennen RM. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 2002;31:231. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Baker BM, Murphy KP. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:2049. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Stroud RM, Finer-Moore JS. Biochemistry. 2003;42:239. doi: 10.1021/bi020598i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hyatt DC, Maley F, Montfort WR. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4585. doi: 10.1021/bi962936j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Stout TJ, Stroud RM. Structure. 1996;4:67. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rutenber EE, Stroud RM. Structure. 1996;4:1317. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fisher HF. Methods in molecular biology. 2012;796:71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-334-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Lee AL, Kinnear SA, Wand AJ. Nature structural biology. 2000;7:72. doi: 10.1038/71280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Frederick KK, Marlow MS, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. Nature. 2007;448:325. doi: 10.1038/nature05959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sapienza PJ, Mauldin RV, Lee AL. Journal of molecular biology. 2010;405:378. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mauldin RV, Carroll MJ, Lee AL. Structure. 2009;17:386. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Marlow MS, Dogan J, Frederick KK, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:352. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kasinath V, Sharp KA, Wand AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15092. doi: 10.1021/ja405200u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Sayre PH, Finer-Moore JS, Fritz TA, Biermann D, Gates SB, MacKellar WC, Patel VF, Stroud RM. Journal of molecular biology. 2001;313:813. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Cardinale D, Guaitoli G, Tondi D, Luciani R, Henrich S, Salo-Ahen OM, Ferrari S, Marverti G, Guerrieri D, Ligabue A, Frassineti C, Pozzi C, Mangani S, Fessas D, Guerrini R, Ponterini G, Wade RC, Costi MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104829108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Brunn ND, Dibrov SM, Kao MB, Ghassemian M, Hermann T. Bioscience reports. 2014;34:e00168. doi: 10.1042/BSR20140137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.