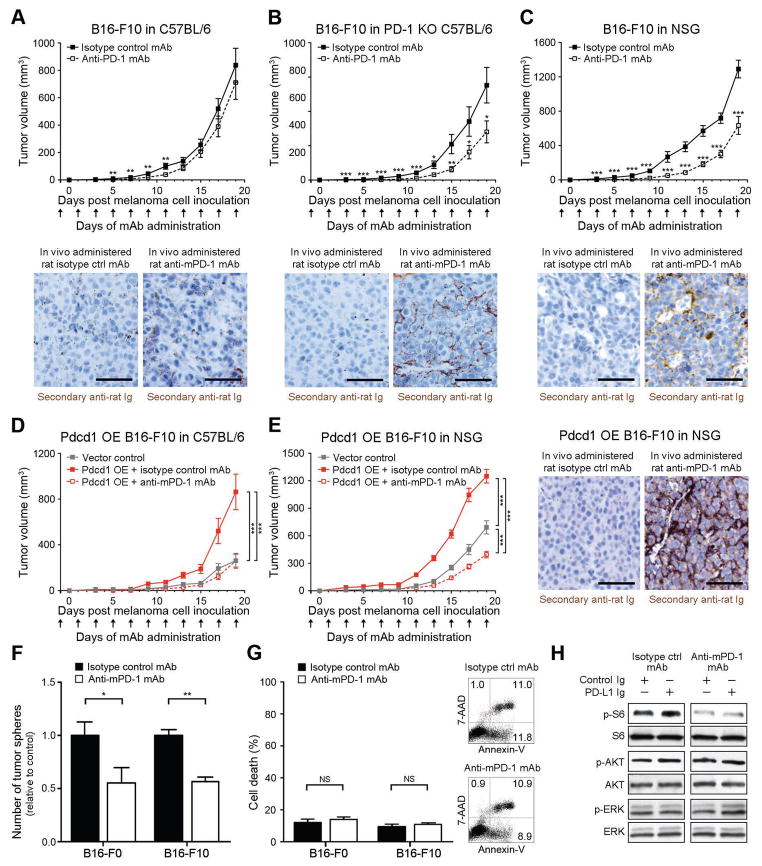

Figure 5. Anti-PD-1 blocking antibody inhibits murine melanoma growth in immunocompetent, immunocompromised and PD-1-deficient tumor graft recipient mice.

(A) Tumor growth kinetics (mean±s.d.) of B16-F10 melanomas in wildtype C57BL/6 (n=32 vs. 34), (B) PD-1(−/−) knockout (KO) C57BL/6 (n=20 vs. 16), and (C) NSG (n=20 vs. 18), and of (D) Pdcd1-overexpressing (OE) vs. vector control B16-F10 melanomas in C57BL/6 (n=10 each) or (E) NSG mice (n=10 each) treated with anti-PD-1- vs. isotype control antibody. Representative immunohistochemical images illustrate binding of in vivo-administered rat anti-mouse PD-1 blocking but not isotype control antibody to the respective B16-F10 melanoma grafts (size bars, 50μm). (F) Mean number of tumor spheres±s.e.m. and (G) flow cytometric assessment of cell death (percent AnnexinV+/7AAD+ cells, mean±s.e.m. (left) and representative flow cytometry plots (right) of anti-PD-1- vs. isotype control mAb-treated murine B16-F0 and B16-F10 melanoma cultures. (H) Immunoblot analysis (representative of n=2 independent experiments) of phosphorylated (p) and total ribosomal protein S6, AKT, and ERK in B16 cultures concurrently treated with PD-L1 Ig vs. control Ig and/or anti-PD-1- vs. isotype control mAb NS: not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). See also Figure S7.