Abstract

Background and objectives

Novel urinary kidney damage biomarkers detect AKI after cardiac surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB-AKI). Although there is growing focus on whether AKI leads to CKD, no studies have assessed whether novel urinary biomarkers remain elevated long term after CPB-AKI. We assessed whether there was clinical or biomarker evidence of long-term kidney injury in patients with CPB-AKI.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We performed a cross-sectional evaluation for signs of chronic kidney injury using both traditional measures and novel urinary biomarkers in a population of 372 potentially eligible children (119 AKI positive and 253 AKI negative) who underwent surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass for congenital heart disease at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center between 2004 and 2007. A total of 51 patients (33 AKI positive and 18 AKI negative) agreed to long-term assessment. We also compared the urinary biomarker levels in these 51 patients with those in healthy controls of similar age.

Results

At long-term follow-up (mean duration±SD, 7±0.98 years), AKI-positive and AKI-negative patients had similarly normal assessments of kidney function by eGFR, proteinuria, and BP measurement. However, AKI-positive patients had higher urine concentrations of IL-18 (48.5 pg/ml versus 20.3 pg/ml [P=0.01] and 20.5 pg/ml [P<0.001]) and liver-type fatty acid–binding protein (L-FABP) (5.9 ng/ml versus 3.9 ng/ml [P=0.001] and 3.2 ng/ml [P<0.001]) than did AKI-negative patients and healthy controls.

Conclusions

Novel urinary biomarkers remain elevated 7 years after an episode of CPB-AKI in children. However, there is no conventional evidence of CKD in these children. These biomarkers may be a more sensitive marker of chronic kidney injury after CPB-AKI. Future studies are needed to understand the clinical relevance of persistent elevations in IL-18, kidney injury molecule-1, and L-FABP in assessments for potential long-term kidney consequences of CPB-AKI.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease; biomarkers; children; acute kidney injury; follow-up studies; humans; kidney; proteinuria; renal insufficiency, chronic

Introduction

AKI after cardiac surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB-AKI) is common, occurring in up to 40% of patients depending on the definition used (1–3). CPB-AKI has been consistently shown to increase both morbidity (4) and mortality (5). Likewise, AKI may also affect quality of life (6) and has an effect on mortality beyond the perioperative period (7).

It previously was assumed that patients with a single episode of AKI would recover kidney function without long-term consequence. However, during the past decade, epidemiologic data from critically ill children (8) and adults (9,10) have suggested that AKI survivors are at considerable risk of developing CKD. Coca et al. (11) demonstrated that adults who experienced AKI have a nine-fold increased risk of developing CKD, a three-fold increased risk of developing ESRD, and a two-fold increased long-term mortality risk compared with those without AKI. Mammen et al. found that 10% of previously critically ill children had developed CKD following AKI, and almost half were considered at risk of CKD (12).

Obstacles to assessing a potential link between AKI and CKD have included lack of a standard AKI definition and reliance on serum creatinine as the primary biomarker to detect and diagnose AKI and CKD. Novel urinary biomarkers of kidney injury, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), IL-18, and liver-type fatty acid–binding protein (L-FABP) measured at different times after CPB have predicted AKI (1). We hypothesize that these novel urinary biomarkers are effective for the detection of ongoing kidney injury and may help identify patients who will progress to CKD. The aims of this study are to (1) evaluate traditional markers of kidney injury at long-term follow-up of patients who did versus those who did not experience AKI after cardiac surgery and (2) evaluate whether these four novel urinary biomarkers remain elevated in patients who experience AKI after cardiac surgery during long-term follow-up.

Materials and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional follow-up study of children who underwent surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) for congenital heart disease at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) between January 2004 and May 2007 and were enrolled in previous CPB-related, AKI biomarker studies (1,2). The institutional review board of CCHMC approved the previous and current studies. Parent caregivers or legal guardians provided informed written consent at the time of initial study enrollment and at long-term evaluation. The parents of potential participants were sent a letter followed by a telephone call. All patients who had CPB-AKI were invited for evaluation as part of the standard of care in the AKI follow-up program at CCHMC; however, only AKI-negative patients from the original cohort who lived within a 25-mile radius of CCHMC were invited (n=80) to serve as controls within this current study. Patients were excluded a priori if they had conditions associated with a high risk of CKD development (anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract, reflux nephropathy, or history of heart transplantation). All participants were evaluated for the present follow-up study from February 2012 to January 2013.

Primary Exposure

The exposure of interest was the development of CPB-AKI at the time of reparative surgery. AKI-positive patients were those who developed a ≥50% rise in their serum creatinine from a preoperative baseline level within 7 days of CPB (13). AKI severity was further stratified by the pediatric modified RIFLE criteria (pRIFLE) using changes in creatinine clearance (3,4). If a patient was enrolled in the initial study more than once, the highest pRIFLE strata were used.

Clinical Data at Time of Primary Exposure

Patient demographic characteristics as well as clinical data at the time of cardiac surgery were compared by both AKI exposure and long-term follow-up status. Novel urinary biomarker values from the time of the original cardiac surgery were used.

Clinical Data at Long-term Follow-Up

Clinical and demographic data were extracted from the medical record and were compared by AKI exposure status. We also extracted echocardiogram and electrocardiogram variables associated with overall cardiac function and chronic fluid overload and/or hypertension that were obtained within the previous year and compared them by exposure status.

Assessment of Chronic Kidney Injury

The primary outcome of interest was the development of chronic kidney injury (CKI) at long-term follow-up. Assessment of CKI by traditional methods included spot urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio (abnormal, >30 μg/mg), casual BP measurement, and eGFR using creatinine-based (both the modified Schwartz and Chronic Kidney Disease in Children equations [16] and cystatin C–based estimating formula [17]). Automated BP readings were used to calculate both systolic BP and diastolic BP percentiles by age, sex, and height as defined by the recommendations of the fourth report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (18).

CKI was also assessed by measuring the following novel urinary biomarker concentrations at the time of long-term follow-up: NGAL, IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP. Urine NGAL, IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP were analyzed as described previously in the literature (19,20). The urine NGAL ELISA was performed using a commercially available assay (NGAL ELISA Kit 036; Bioporto, Grusbakken, Denmark) that specifically detects human NGAL. Urine IL-18 and L-FABP were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (Medical & Biologic Laboratories Co., Nagoya, Japan, and CMIC Co., Tokyo, Japan, respectively) per the manufacturers’ instructions. The urine KIM-1 ELISA was constructed using commercially available reagents (Duoset DY1750, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as described previously (20). Laboratory investigators were blinded to clinical outcomes. In patients who had biomarker measurements at all three times points of interest (preoperative, 24-hour postoperative, and present-day measurements), the change or difference in the biomarker was calculated.

Comparison of Urinary Biomarker Concentrations in Healthy Controls

Urinary biomarker concentrations from 90 healthy controls of similar age (5–10 years) were compared with those in the longitudinal follow-up cohort. Methods used to measure these biomarkers have been reported in the literature (21) and are the same as those used on the samples obtained from research participants at long-term follow-up.

Statistical Analyses

Univariate associations between potential outcomes of interest and AKI exposure were assessed using a t test, Wilcoxon rank-sum, or Kruskal–Wallis test for normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, and chi-squared or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test (non-normal distribution) was used to determine the statistical significance of the change in the urinary biomarker over time (higher, lower, or no difference); a one-sided P value was used because we hypothesized that AKI-positive patients would have higher urinary biomarkers at long-term assessment. When multiple comparisons were evaluated, a Bonferroni adjustment (P value/n−1) was applied (P<0.05/n−1 was considered to represent statistical significance for comparisons). In addition, all biomarker values at long-term follow-up were log-transformed and compared by one-way ANOVA. If a difference was detected, a Tukey multiple comparison test was completed to determine which group(s) demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the biomarker concentrations. Otherwise, a two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant finding. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Study Cohort

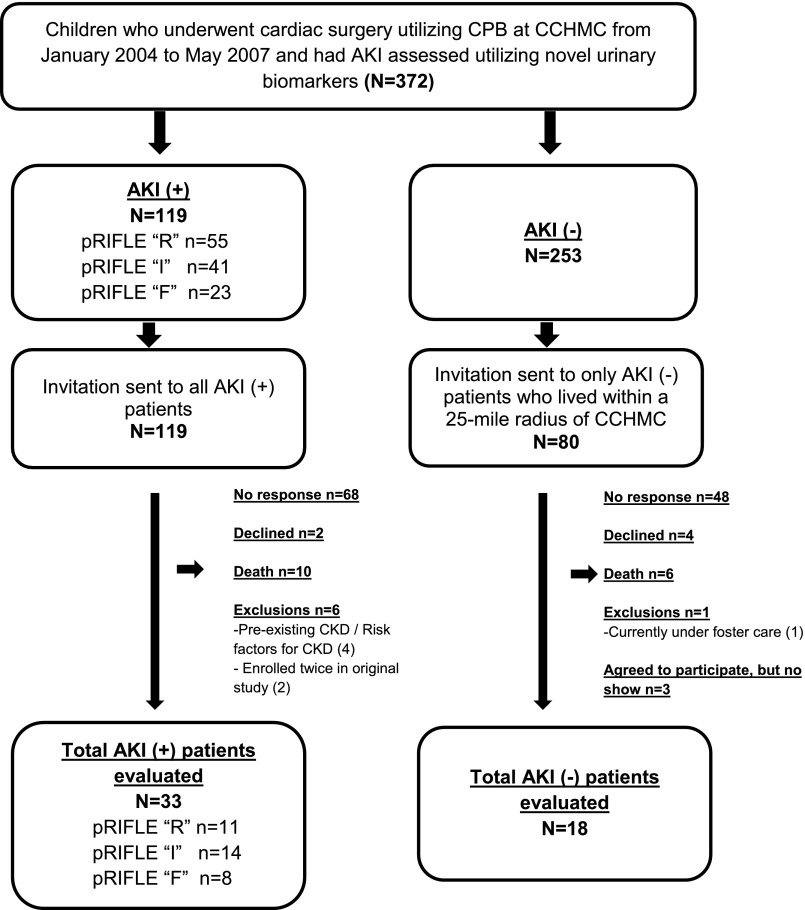

There were 372 potentially eligible children who underwent CPB for congenital heart disease repair at CCHMC between January 2004 and May 2007 and were enrolled in prior CPB-related AKI biomarker studies. Of the 372 patients, 119 were AKI positive and 253 were AKI negative. Four patients were enrolled more than once during the original study. Only one patient developed AKI on both observations (pRIFLE-I and then pRIFLE-R), and one patient developed AKI during one of the two observations. The other two patients never developed AKI after CPB. A total of 33 AKI-positive and 18 AKI-negative patients were enrolled in our present longitudinal follow-up study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient selection flow diagram. Children enrolled in prior cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (CPB)–related studies of novel AKI biomarkers who did and did not have AKI at the time of their initial CPB were identified and invited back for long-term follow-up. AKI was determined by increase in serum creatinine and novel urinary biomarkers. CCHMC, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Clinical Data from Original Patient Cohort by AKI Exposure and Long-Term Follow-Up Status

Among all AKI-positive patients in the original cohort, 24-hour postoperative urine L-FABP/creatinine concentration was higher in those who participated in follow-up evaluation. Otherwise, patient demographic and perioperative clinical variables did not significantly differ between AKI-positive patients who did versus those who did not undergo follow-up evaluation (Table 1, column C). Likewise, the severity of the postoperative course (according to postoperative day 2 inotrope score), AKI severity (according to pRIFLE subclassification) and AKI duration were similar among patients who did versus those who did not participate in follow-up evaluation.

Table 1.

Comparison of preoperative and immediate postoperative clinical data of total cohort of patients by both AKI after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery exposure and long-term follow-up status

| Variable | CPB-AKI–Positive Patients, by Follow-Up Status (n=119) | AKI-Negative Patients, by Follow-Up Status (n=253) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Follow-Up Positive (n=33) | B: Follow-Up Negative (n=86) | C: P Value (Column A versus Column B)a | D: Follow-Up Positive (n=18) | E: Follow-Up Negative (n=235) | F: P Value (Column D versus Column E)b | G: P Value (Column A versus Column D)c | |

| Age at surgery, yr | 0.51 (0.34, 1.38) | 0.54 (0.35, 0.99) | 0.14 | 0.57 (0.25, 3.15) | 2.8 (0.51, 5.9) | 0.01 | 0.79 |

| Male, n (%) | 16 (48.5) | 44 (51.2) | 1.00 | 8 (44.4) | 130 (55.3) | 0.46 | >0.99 |

| White, n (%) | 32 (100) | 73 (85) | 0.24 | 18 (100) | 201 (87) | 0.62 | >0.99 |

| No history of CPB, n (%) | 21 (63.6) | 59 (68.6) | 0.66 | 11 (61) | 125 (53) | 0.63 | >0.99 |

| Baseline serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.3 (0.3, 0.4) | 0.3 (0.3, 0.4) | 0.90 | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) | 0.4 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.19 | 0.02 |

| Baseline eCCL, ml/min per 1.73 m2 (14) | 97.5 (85.5, 134.75) | 99 (71.44, 140.63) | 0.94 | 96 (74.25, 116.6) | 112.2 (79.31, 132.92) | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| RACHS-1 score, n (%) (15) | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.21 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 6 (7) | 2 (11.1) | 28 (11.9) | |||

| 2 | 15 (45.5) | 46 (53.5) | 8 (44.4) | 107 (45.5) | |||

| 3 | 15 (45.5) | 28 (32.5) | 5 (27.8) | 87 (37) | |||

| 4 | 1 (3) | 3 (3.5) | 2 (11.1) | 7 (3) | |||

| 5 | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 2 (0.9) | |||

| 6 | 0 | 3 (3.5) | 0 | 4 (1.7) | |||

| CPB time, min | 136 (104, 175) | 121 (84, 182) | 0.72 | 93.5 (82, 138) | 92 (68, 127) | 0.42 | 0.10 |

| Highest postoperative serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 0.23 | 0.4 (0.4, 0.5) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| Lowest postoperative eCCL, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 45 (36.56, 59.09) | 52.65 (39.31, 70.82) | 0.26 | 75.38 (59.4, 102.44) | 106.7 (70.88, 131.31) | 0.07 | 0.003 |

| Change in serum creatinine, % | 100 (67.67, 133.33) | 75 (60, 100) | 0.14 | 22.5 (0, 33.33) | 0 (0, 25) | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| pRIFLE, n (%) | 0.22 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| R | 11 (33.2) | 44 (51.2) | |||||

| I | 14 (42.4) | 27 (31.4) | |||||

| F | 8 (24.2) | 15 (17.4) | |||||

| Duration of AKI, d | 2 (2, 3) | 2 (2, 3) n=79 | 0.94 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Inotrope score on postoperative d 2 | 3 (0, 7.5) | 0 (0, 12) n=83 | 0.33 | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 7.5) | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 9 (5, 20) | 8.5 (5, 19) | 0.90 | 6 (4, 22) | 5 (3, 8) | 0.13 | 0.23 |

| Death within 1 mo of original surgery, n (%) | NA | 5 (5.8) | NA | NA | 2 (1) | NA | NA |

| Preoperative urine biomarkers | |||||||

| NGAL/Cr, ng/mg | 18.18 (11.11–29.09); n=33 | 18.33 (10–27.78); n=86 | 0.70 | 12.91 (4.17–18.75); n=18 | 8.33 (3.57–15); n=234 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| IL-18/Cr, pg/mg | 5.21 (0–24.67); n=15 | 0.59 (0–12.38); n=44 | 0.32 | 0 (0–4.12); n=10 | 2.59 (0–12.31); n=133 | 0.1 | 0.23 |

| KIM-1/Cr, pg/mg | 194.63 (168.05–235.03); n=13 | 284.2 (138.7–448.89); n=39 | 0.46 | 261.37 (215.42–505.73); n=10 | 243.1 (168.13–352.68); n=107 | 0.66 | 0.16 |

| L-FABP/Cr, ng/mg | 18.14 (5.21–49.63); n=15 | 8.08 (3.31–32.1); n=43 | 0.24 | 19.6 (0–58.33); n=11 | 12.75 (2.65–34.67); n=133 | 0.78 | 0.45 |

| 24-h postoperative urine biomarkers | |||||||

| NGAL/Cr, ng/mg | 220 (86.15–562.67); n=33 | 121.32 (39.53–304); n=86 | 0.02 | 18.46 (10–27.27); n=17 | 17.99 (6.67–34.29); n=234 | 0.73 | <0.001 |

| IL-18/Cr, pg/mg | 77.27 (36.67–170.67); n=15 | 64.23 (28.89–155.8); n=44 | 0.51 | 17.06 (0–40.67); n=10 | 12.5 (0–38.18); n=133 | 0.88 | 0.001 |

| KIM-1/Cr, pg/mg | 1861.29 (931.83–3881.82); n=15 | 1313.06 (644.06–2517.64); n=44 | 0.28 | 745.51 (245.9–1345.72); n=10 | 520.47 (227.92–972.61); n=125 | 0.38 | 0.01 |

| L-FABP/Cr, ng/mg | 876.86 (445.1–1190.38); n=14 | 301.66 (168.66–825.27); n=41 | 0.01 | 69.13 (18.69–360.49); n=10 | 107.97 (27.9–280.48); n=125 | 0.55 | 0.001 |

Unless otherwise noted, values are expressed as median (interquartile range). Level of significance: P<0.02. CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass surgery; eCCL, estimated creatinine clearance; NA, not applicable; RACHS-1, risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery; R, risk; I, injury; F, failure; ICU, intensive care unit; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; Cr, creatinine; KIM, kidney injury molecule; L-FABP, liver fatty acid–binding protein.

Column C: P values for comparisons between all patients who developed AKI after surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB-AKI), by long-term follow-up status: column A (follow-up) versus column B (no follow-up).

Column F: P values for comparisons between all patients who did not develop CPB-AKI, by long-term follow-up status: column D (follow-up) versus column E (no follow-up).

Column G: P values for comparisons between all patients who agreed to long-term follow-up, by CPB-AKI exposure status: column A (CPB-AKI positive) versus column D (CPB-AKI negative).

Among AKI-positive patients, those who participated in follow-up evaluation were younger at the time of CPB than those who did not (0.57 versus 2.8 years; P=0.01). All other perioperative and postoperative clinical data were similar between the AKI-positive patients who did versus those who did not undergo follow-up evaluation (Table 1, column F).

Clinical Data at Follow-Up Evaluation

Evaluation occurred a mean±SD of 7±0.98 years after original cardiac surgery. AKI-positive and AKI-negative patients did not differ for age, time since original CPB surgery, current serum creatinine concentrations, or mean eGFR (Table 2). In a subset of 25 patients who had a cystatin C measured at follow-up (17 AKI-positive and eight AKI-negative patients), we also observed no difference in cystatin C eGFR according to the 2012 Chronic Kidney Disease in Children formula. After exclusion of patients with a bedside Schwartz eGFR<75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at long-term follow-up, there were no significant differences when comparing biomarker concentrations between healthy controls (n=90), AKI-negative patients (n=18), and AKI-positive patients (n=26) (results not shown). Nine patients were prescribed ten antihypertensive medications (eight angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, one diuretic, and one calcium channel blocker); most patients were prescribed angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for afterload reduction. Spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratios were similar between groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of traditional markers of kidney injury and cardiac data at long-term follow-up

| Variable | AKI-Positive Patients (n=33) | AKI-Negative Patients (n=18) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at evaluation, yr | 7.9 (6.9, 8.7) | 8.25 (7.2, 9.6) | 0.36 |

| Time since CPB, yr | 6.9±1 | 7.13±0.96 | 0.43 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.47 (0.41, 0.5); n=24 | 0.50 (0.44, 0.62); n=12 | 0.26 |

| eGFR (Schwartz), ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 108.82±20.76 | 105.1±17.38 | 0.62 |

| Patients with eGFR<90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 3 (14.3); n=21 | 3 (27); n=11 | 0.39 |

| Patients with eGFR>150 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

| eGFR (cystatin C), ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 120 (102, 126); n=21 | 118 (113, 118); n=9 | 0.39 |

| eGFR (CKiD), ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 97.89±11.66; n=17 | 97.89±11.66; n=8 | 0.65 |

| Height Z-scores | −0.81±0.93; n=28 | −0.38±1.35; n=17 | 0.28 |

| BP | |||

| SBP percentile | 52.23±28.32; n=28 | 61.36±24.37; n=17 | 0.26 |

| DBP percentile | 51.18±22.72; n=28 | 59.68±22.7; n=17 | 0.21 |

| Patients with SBP>90th percentile, n/n | 3/28 | 2/17 | >0.99 |

| Patients with DBP>90th percentile, n/n | 1/28 | 0/17 | >0.99 |

| Patients taking any antihypertensive medications, n (%) | 7 (21.2) | 2 (11) | 0.46 |

| Total no. of antihypertensive medications prescribed per patient, n | |||

| 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Class of antihypertensive medication, n (%) | |||

| ACE inhibitor | 6 | 2 | |

| β-blocker | 1 | 0 | |

| Diuretic | 1 | 0 | |

| Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, mg/mg | 0.19±0.08; n=23 | 0.18±0.08; n=11 | 0.77 |

| Urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio, μg/mg | 13.5 (6.9, 15.7); n=26 | 11.67 (6.18, 28.49); n=13 | 0.89 |

| Patients with urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥30 μg/mg, n (%) | 1 (3.9) | 3 (23) | 0.27 |

| Echocardiogram findings | |||

| RV diastolic dimension, cm | 1.94 (1.63, 2.28); n=10 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.02); n=3 | 0.45 |

| LV diastolic dimension, cm | 3.54 (3.45, 3.9); n=10 | 3.88 (3.86, 4.15); n=5 | 0.36 |

| LV diastolic wall thickness, cm | 0.6 (0.56, 0.65); n=13 | 0.61 (0.53, 0.62); n=5 | 0.73 |

| LV fractional shortening,% | 37.68 (36.46, 40.06); n=12 | 34.95 (34.79, 40.24); n=5 | 0.71 |

| LV mass/height2.7 | 34 (29.81, 39.91); n=12 | 33.62 (31.7, 39.25); n=5 | 0.79 |

| Electrocardiogram findings, n/n (%) | |||

| RVH | 4/23 (17.4) | 2/12 (16.7) | >0.99 |

| LVH | 1/23 (4.35) | 0/12 (0) | >0.99 |

| Patients with ≥1 serum creatinine measurement at any time from CPB exposure to long-term follow-up assessment, n (%) | 15/33 (45) | 8/18 (44) | >0.99 |

| Patients requiring repeat hospitalization since time of original surgery, n (%) | 29/33 (88) | 13/18 (72) | 0.25 |

Unless otherwise noted, values are the median (interquartile range). Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD. Level of significance: P<0.05. CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; CKiD, Chronic Kidney Disease in Children; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; RV, right ventricular; LV, left ventricular; RVH, right ventricular hypertrophy; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

Twenty-five percent of the entire cohort (n=13; ten AKI-positive and three AKI-negative) had an echocardiographic assessment, and 67% of the cohort (n=35; 23 AKI-positive and 12 AKI-negative) had an electrocardiographic assessment within the past year. Although no generalizable comparisons can be made by exposure status given the limited number of echocardiograms, all measurements were normal.

Before follow-up evaluation, approximately half of the cohort (15 AKI-positive and eight AKI-negative) had at least one serum creatinine measurement performed after their original cardiac surgery hospitalization, with no difference between the groups. In addition, rates of repeat hospitalization to CCHMC were similar between the AKI-positive and AKI-negative patients (Table 2).

Novel Urinary Biomarkers at Long-Term Follow-Up

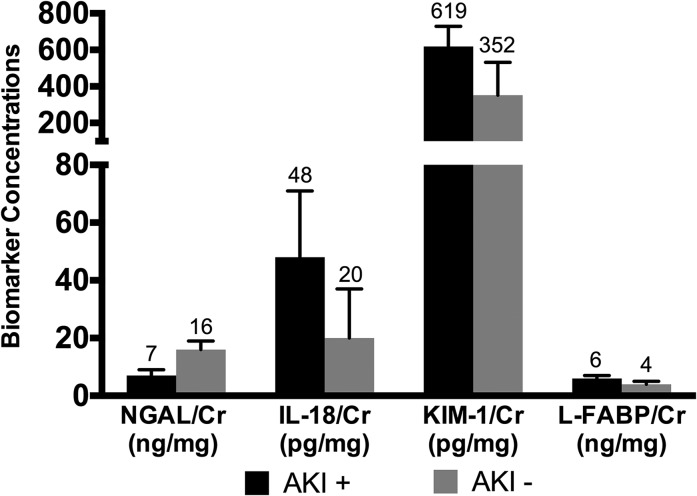

At the time of longitudinal follow-up, AKI-positive patients had higher urinary concentrations of IL-18 (48.5 pg/ml versus 20.3 pg/ml; P=0.01), KIM-1 (619 pg/ml versus 352.4 pg/ml; P=0.03), and L-FABP (5.9 ng/ml versus 3.9 ng/ml; P=0.001) but lower urine NGAL concentrations (7 ng/ml versus 15.7 ng/ml; P=0.01) compared with AKI-negative patients (Figure 2). Comparison of the four urinary biomarker concentrations among only the AKI-positive patients by pRIFLE strata subgroup analysis (pRIFLE-R versus pRIFLE-I/F) showed no significant differences at long-term follow-up (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Novel urinary biomarkers are elevated in previously AKI-positive patients at long-term follow-up. Median biomarker concentrations at the time of longitudinal follow-up are displayed for AKI-positive (n=30 except for liver fatty acid–binding protein [L-FABP], for which n=29) compared with AKI-negative (n=18) patients. Error bars represent 25th and 75th percentiles. Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

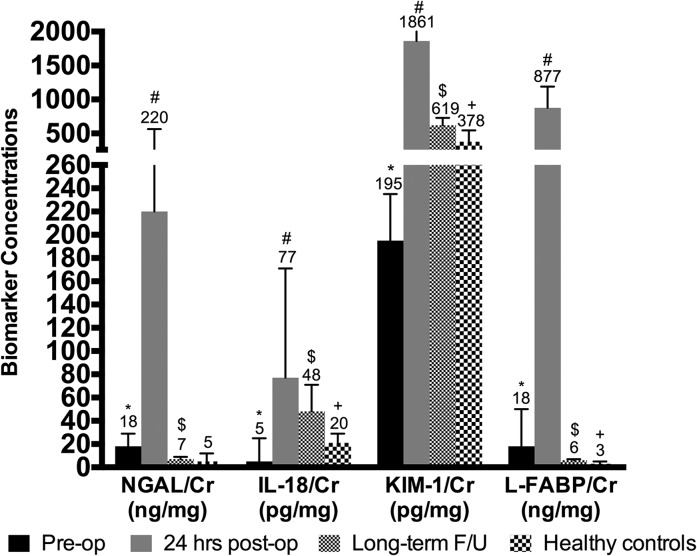

In a limited subset of patients who had biomarkers available at all three time points (before CPB, 24 hours after CPB, and at follow-up), all four biomarker concentrations were higher at 24 hours after CPB than at baseline before CPB and were lower at long-term follow-up than at 24 hours after CPB. However, urinary IL-18 and KIM-1 concentrations were higher, while NGAL and L-FABP concentrations were lower, at long-term follow-up compared with preoperative values (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Biomarkers are elevated post-cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (CPB) in AKI-positive patients and remain elevated at long-term follow-up (F/U) compared to healthy age-matched patients. Median biomarker concentrations at pre-CPB baseline were compared with those 24 hours after CPB (*P<0.05). Median biomarker concentrations at long-term follow-up were compared with those 24 hours after CPB (#P<0.05). Median biomarker concentrations at long-term follow-up were compared with pre-CPB baseline values ($P<0.05). Finally, median biomarker concentrations at long-term follow-up were compared with those of healthy age-matched controls (+P<0.05). Error bars represent 25th and 75th percentiles. * denotes P value for comparison between baseline pre-CPB and 24-hour post-CPB biomarker concentrations; # denotes P value for comparison between long-term and 24-hour post-CPB biomarker concentrations; $ denotes P value for comparison between long-term and pre-CPB biomarker concentrations; + denotes P value for comparison between long-term and healthy age-matched control biomarker concentrations. Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; L-FABP, liver fatty acid–binding protein; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

When we compared urinary biomarker concentrations between AKI-positive patients (n=30), AKI-negative patients (n=18), and similarly aged healthy controls (n=45 boys and 45 girls; mean age, 7.43±1.43 years), AKI-positive patients had higher creatinine-normalized IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP values; AKI-negative patients had higher urine NGAL concentrations. Further analysis comparing urinary biomarker concentrations of AKI-positive patients to all patients without AKI (AKI-negative patients plus healthy controls, n=108) demonstrated no difference in urine NGAL concentrations but did show statistically significant elevations of urinary IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP. When the analysis was repeated on log-transformed biomarker concentrations, AKI-positive patients versus AKI-negative versus healthy controls still had higher IL-18 (1.69±0.28 pg/ml versus 1.43±0.35 pg/ml versus 1.34±0.22 pg/ml; P<0.001) and L-FABP (0.79±0.24 ng/ml versus 0.52±0.27 ng/ml versus 0.48±0.36 ng/ml; P<0.001) concentrations, but the differences for KIM-1 (2.69±0.31 pg/ml versus 2.56±0.35 pg/ml versus 2.56±0.27 pg/ml; P=0.12) and NGAL (0.77±0.38 ng/ml versus 1.02±0.54 ng/ml versus 0.76±0.54 ng/ml; P=0.14) lost statistical significance. Urinary concentrations of IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP did not significantly differ in AKI-negative patients and healthy controls (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparisons of urinary biomarkers in AKI-positive and AKI-negative patients at long-term follow-up from cardiopulmonary bypass surgery versus healthy controls

| Variable | A: AKI-Positive Patients (n=30) | B: AKI-Negative Patients (n=18) | C: Healthy Controls (n=90) | D: AKI-Negative Patients and Healthy Controls (n=108) | P Value (Columns A, B, and C)a | P Value (Column A versus Column B) b | P Value (Column A versus Column D)b | P Value (Column B versus Column C)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine NGAL/Cr, ng/mg | 7.01 (4.03, 9.46) | 15.65 (9.598, 19.213) | 4.81 (2.61, 11.63) | 5.51 (2.96, 15.652) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.01 |

| Urine IL-18/Cr, pg/mg | 48.496 (39.05, 70.84) | 20.27 (16.08, 37.16) | 20.68 (14.6, 29.32) | 20.492 (14.917, 29.864) | <0.001 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Urine KIM-1/Cr, pg/mg | 619.02 (437.57, 728.88) | 352.407 (231.574, 532.432) | 378.408 (273.164, 545.486) | 378.41 (262.24, 537.55) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.002 | 0.63 |

| Urine L-FABP/Cr, ng/mg | 5.88 (4.74, 7.44) n=29 | 3.9 (2.81, 5.4) | 3.07 (1.9, 4.87) | 3.18 (1.9, 5.11) | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.40 |

Values are expressed as the median (interquartile range). NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; L-FABP, liver fatty acid–binding protein.

P=0.05.

P=0.02 (0.05/n−1; n=4).

Discussion

In this study, the first long-term follow-up assessment of novel urinary biomarkers in a pediatric population who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass, we found evidence of persistent elevations in IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP concentrations in patients who developed AKI compared with those who did not develop AKI. Conventional markers of kidney impairment did not differ between those who did versus those who did not develop AKI. In addition, despite a limited sample size, we were able to demonstrate a persistent elevation in KIM-1 and IL-18 concentrations at long-term evaluation compared with the perioperative baseline values in patients who developed AKI at the time of cardiac surgery. Finally, we showed statistically significant elevations in urinary concentrations of IL-18, KIM-1, and L-FABP at present-day evaluation in AKI-positive patients compared with both AKI-negative patients and healthy controls of similar age.

The development of standardized AKI definitions has allowed for a more thorough understanding of pediatric AKI epidemiology, but long-term renal clinical outcomes after AKI in critically ill children and neonates have not been well established. The damage induced by subclinical or manifested episodes of AKI may produce irreversible loss of renal mass with deleterious effects on overall renal function. In follow-up studies of pediatric AKI, the incidence of CKD ranges from 27% to 67% (8,22). Mammen et al. demonstrated a 10% incidence of CKD 1–3 years after AKI in a critically ill population (including postoperative cardiac patients) according to a standardized AKI definition/classification system (12). However, the implications of CPB-AKI are less clear.

Given the known limitations of traditional biomarkers to detect AKI early, attention has focused on the utility of urinary biomarkers (e.g., NGAL, KIM-1, IL-18, and L-FABP) to not only improve AKI diagnosis but follow and predict rapid CKD progression in both pediatric and adult CKD populations. A combination of biomarkers such as NGAL and KIM-1 may provide complementary information in real-time, wherein NGAL reflects more acute inflammatory events and KIM-1 reflects more chronic, fibrotic changes. This would be a plausible explanation of why the NGAL levels were lower in AKI-positive patients at the time of follow-up. The correlation of L-FABP is not as clear, but this biomarker may have greater ability to detect chronic injury because it is elevated in AKI-positive patients at follow-up but is lower than preoperative levels. Preliminary studies have reported on the potential utility of KIM-1 as a CKD biomarker (23,24). Animal models of AKI-to-CKD transition have identified NGAL and KIM-1 as two of the most upregulated genes and proteins in the kidney, revealing a possible role for these proteins as potential biomarkers to predict risk of CKD after AKI (25). The persistent elevation in KIM-1 and IL-18 in AKI-positive patients suggests ongoing kidney injury.

Inflammation, a common mechanism for CPB-AKI, is postulated as another mechanism for ongoing kidney injury; CKD is associated with a chronic inflammatory process. Both IL-18 and L-FABP are urinary biomarkers whose production is more specific toward inflammatory pathophysiology within the renal environment. Kamijo et al. demonstrated that in patients with mild nondiabetic CKD, significantly higher L-FABP levels were associated with a more rapid rate of CKD progression. Notably, neither serum creatinine nor urine protein differed between patients who did versus those who did not experience rapid CKD progression (26), similar to our study findings. The elevated urinary IL-18 and L-FABP levels in the AKI-positive patients in our cohort could support ongoing inflammation as a source of kidney injury.

Although the AKI-positive patients in our cohort did not have any classic findings indicating chronic renal injury (such as abnormalities in clearance according to eGFR, proteinuria, or hypertension), these AKI-positive patients have persistently elevated urinary biomarker concentrations consistent with ongoing injury. This discrepancy could potentially be explained by changes in renal functional reserve after AKI exposure. Renal function reserve is an indirect method of measuring renal mass by assessing how well the kidney can metabolically compensate under metabolic stress (27). After an episode of AKI, there is likely to be variable injury to functional renal mass and renal reserve, increasing the risk of CKD development. We postulate that in our cohort, AKI-positive patients probably have reduced renal function reserve; however, given the kidney’s ability to sufficiently compensate for reduced renal mass, routine assessments of renal function might not adequately reflect the actual anatomic and functional limitations of the kidney parenchyma. The clinical significance is not yet evident but does suggest the possibility that once functional renal reserve is diminished, subclinical renal impairment may become evident.

Despite limited follow-up, AKI-positive patients did not appear to have a more complex postoperative clinical course (more nonrenal complications), more repeat episodes of AKI, or higher hospitalization rates compared with AKI-negative patients. We therefore postulate that the difference in the urinary biomarkers at long-term follow-up is secondary to the development of AKI almost 7 years earlier.

Importantly, compared with age-matched healthy children and AKI-negative patients, AKI-positive patients had elevated urinary concentrations of KIM-1, IL-18, and L-FABP, although the KIM-1 finding lost statistical significance after log-transformation to improve the distribution of the data. This would further support our assertions that these elevations represent renal pathology. We also assessed the pattern of change for biomarkers at long-term assessment from perioperative baseline. Despite a limited sample size, KIM-1 and IL-18 remained persistently elevated in the AKI-positive patients. We speculate that these children may be at an increased risk for future kidney damage, especially as they mature and require intensive medical and surgical interventions. In fact, 50% of young adults with congenital heart disease have impaired GFR, even those with simple defects (28).

Our study does have important limitations. First, there are intrinsic limitations to a cross-sectional follow-up study, such as differences in baseline characteristics and/or selection bias (which might not have been recorded), as well as time-dependent changes in outcome. It is possible that during the interim period, an undocumented acute and/or chronic insult could have occurred. Second, this is a single-center study with a small sample size and low retention rate, which requires validation at the multicenter level. This small sample size probably contributed to the loss of significance in the KIM-1 comparisons after log-transformation of the data. Third, our results may not be generalizable to adults undergoing CPB or to the myriad other clinical scenarios that commonly lead to AKI in hospitalized patients. Finally, biomarker levels were not measured throughout the follow-up interval, thereby making the exact biomarker pattern and timing of increase in our study population uncertain. All these limitations make the general applicability of these findings difficult. However, the study does have several strengths. First, we enrolled a relatively homogenous cohort of participants in whom the most proximate cause for AKI would be CPB. Second, the patients with AKI evaluated at follow-up had AKI severity similar to that of patients who did not undergo long-term evaluation. Third, the definition of AKI in the original cohort was based on elevations in serum creatinine, making it likely that we identified only patients with greater than mild injury.

Our study evaluated patients 7 years after CPB, and although there is no conventional evidence of CKD there is evidence of urinary biomarker elevation. Thus, it is important to follow these children throughout adulthood to understand the full clinical implications of these urinary biomarkers elevations because they could be a more sensitive marker of CKI after CPB-AKI.

Disclosures

P.D. is a coinventor on patents relating to the use of NGAL as a biomarker of renal injury and has licensing agreements with Abbott Diagnostics (Abbott Park, IL) and Alere, Inc. (Waltham, MA). There are no other disclosures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (P50 DK096418).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Krawczeski CD, Goldstein SL, Woo JG, Wang Y, Piyaphanee N, Ma Q, Bennett M, Devarajan P: Temporal relationship and predictive value of urinary acute kidney injury biomarkers after pediatric cardiopulmonary bypass. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 2301–2309, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra J, Dent C, Tarabishi R, Mitsnefes MM, Ma Q, Kelly C, Ruff SM, Zahedi K, Shao M, Bean J, Mori K, Barasch J, Devarajan P: Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) as a biomarker for acute renal injury after cardiac surgery. Lancet 365: 1231–1238, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis LL, Washburn KK, Jefferson LS, Goldstein SL: Modified RIFLE criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 71: 1028–1035, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zappitelli M, Bernier PL, Saczkowski RS, Tchervenkov CI, Gottesman R, Dancea A, Hyder A, Alkandari O: A small post-operative rise in serum creatinine predicts acute kidney injury in children undergoing cardiac surgery. Kidney Int 76: 885–892, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lassnigg A, Schmidlin D, Mouhieddine M, Bachmann LM, Druml W, Bauer P, Hiesmayr M: Minimal changes of serum creatinine predict prognosis in patients after cardiothoracic surgery: A prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1597–1605, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg R, Dennen P: Long-term outcomes of acute kidney injury. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 15: 297–307, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JR, Kramer RS, Coca SG, Parikh CR: Duration of acute kidney injury impacts long-term survival after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 90: 1142–1148, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Askenazi DJ, Feig DI, Graham NM, Hui-Stickle S, Goldstein SL: 3-5 year longitudinal follow-up of pediatric patients after acute renal failure. Kidney Int 69: 184–189, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo LJ, Go AS, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Hsu CY: Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 76: 893–899, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishani A, Nelson D, Clothier B, Schult T, Nugent S, Greer N, Slinin Y, Ensrud KE: The magnitude of acute serum creatinine increase after cardiac surgery and the risk of chronic kidney disease, progression of kidney disease, and death. Arch Intern Med 171: 226–233, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR: Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 961–973, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mammen C, Al Abbas A, Skippen P, Nadel H, Levine D, Collet JP, Matsell DG: Long-term risk of CKD in children surviving episodes of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: A prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 523–530, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidney Disease. Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney IntSuppl 2: 1–138, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Jr, Spitzer A: A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 58: 259–263, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wernovsky G, Giglia TM, Jonas RA, Mone SM, Colan SD, Wessel DL: Course in the intensive care unit after ‘preparatory’ pulmonary artery banding and aortopulmonary shunt placement for transposition of the great arteries with low left ventricular pressure. Circulation 86[Suppl]: II133–II139, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL: New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 629–637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson A, Malm J, Grubb A, Hansson LO: Calculation of glomerular filtration rate expressed in mL/min from plasma cystatin C values in mg/L. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 64: 25–30, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents : The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 114[Suppl 4th Report]: 555–576, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett M, Dent CL, Ma Q, Dastrala S, Grenier F, Workman R, Syed H, Ali S, Barasch J, Devarajan P: Urine NGAL predicts severity of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: A prospective study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 665–673, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaturvedi S, Farmer T, Kapke GF: Assay validation for KIM-1: Human urinary renal dysfunction biomarker. Int J Biol Sci 5: 128–134, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett MR, Nehus E, Haffner C, Ma Q, Devarajan P: Pediatric reference ranges for acute kidney injury biomarkers. Pediatr Nephrol 30: 677–685, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw NJ, Brocklebank JT, Dickinson DF, Wilson N, Walker DR: Long-term outcome for children with acute renal failure following cardiac surgery. Int J Cardiol 31: 161–165, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Timmeren MM, Vaidya VS, van Ree RM, Oterdoom LH, de Vries AP, Gans RO, van Goor H, Stegeman CA, Bonventre JV, Bakker SJ: High urinary excretion of kidney injury molecule-1 is an independent predictor of graft loss in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 84: 1625–1630, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waanders F, Vaidya VS, van Goor H, Leuvenink H, Damman K, Hamming I, Bonventre JV, Vogt L, Navis G: Effect of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition, dietary sodium restriction, and/or diuretics on urinary kidney injury molecule 1 excretion in nondiabetic proteinuric kidney disease: A post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 16–25, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko GJ, Grigoryev DN, Linfert D, Jang HR, Watkins T, Cheadle C, Racusen L, Rabb H: Transcriptional analysis of kidneys during repair from AKI reveals possible roles for NGAL and KIM-1 as biomarkers of AKI-to-CKD transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1472–F1483, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamijo A, Sugaya T, Hikawa A, Yamanouchi M, Hirata Y, Ishimitsu T, Numabe A, Takagi M, Hayakawa H, Tabei F, Sugimoto T, Mise N, Omata M, Kimura K: Urinary liver-type fatty acid binding protein as a useful biomarker in chronic kidney disease. Mol Cell Biochem 284: 175–182, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronco C, Rosner MH: Acute kidney injury and residual renal function. Crit Care 16: 144–145, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimopoulos K, Diller GP, Koltsida E, Pijuan-Domenech A, Papadopoulou SA, Babu-Narayan SV, Salukhe TV, Piepoli MF, Poole-Wilson PA, Best N, Francis DP, Gatzoulis MA: Prevalence, predictors, and prognostic value of renal dysfunction in adults with congenital heart disease. Circulation 117: 2320–2328, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]