Abstract

Recent developments in the study of health and social networks have focused on linkages between health outcomes and naturally occurring social relations, such as friendship or kinship. Based on findings in this area, a new generation of health behavior intervention programs have been implemented that rely on the formation of new social relations among program participants. However, little is known about the qualities of these de novo social relations. We examined the social networks of 59 participants within a randomized controlled trial of an intervention designed to prevent excessive gestational weight gain. We employed exponential random graph modeling techniques to analyze supportive relationships formed between participants in the intervention arm, to detect unique effects of program participation on the likelihood of forming ties. Program participation had a positive effect on the likelihood of forming supportive social relations, however, in this particular timeframe we did not detect any additional effect of such relations on the health behaviors or outcomes of interest. Our findings raise two critical questions: do short‐term group‐level programs reliably lead to the formation of new social relations among participants; and do these relations have a unique effect on health outcomes relative to standard methods of health behavior intervention?

Keywords: social networks, behavior, health intervention

Introduction

A social network is defined as a set of people connected by a set of social relationships, such as friendship, kinship, coworking, or information exchange. Each of us belongs to multiple social networks simultaneously that exert powerful influences over our behavior. Research on social networks has demonstrated linkages between the health behaviors of members of one's social networks (acquaintances, friends, and family), and one's own health behaviors and outcomes. Examples include behaviors such as smoking,1, 2, 3 alcohol consumption,4, 5 and physical activity,6, 7, 8, 9 and health outcomes such as weight status.9, 10, 11 Together, the evidence points to social networks as a promising method for intentionally spreading health information and health behaviors through communities.12, 13

Recent widespread interest in the influential nature of social relations, combined with ongoing interest in positive effects of social support on a range of health outcomes, have given rise to new kinds of health interventions that include activities and settings for participants to build new social ties and give/receive social support related to aspects of program content. One example is the practice of group prenatal care,14, 15, 16, 17 in which expecting mothers receive medical care and child birth education in a setting that fosters the formation of new social relations among program cohort members. Previous research suggests that those involved in prenatal group care programs report increased levels of social support16, 18—a factor positively associated with birth weight.19, 20, 21

While much has been published about the beneficial effects of social support in health intervention settings, very little work has analyzed in detail the social networks formed among participants of such interventions (e.g., which type of ties form, how they influence participant behavior and mediate program outcomes). Many important questions remain regarding the potential differences between de novo, adjacent social ties formed in an intervention setting, and existing relations such as kin and friendship (the typical focus of most literature on social networks and health).

In this study, we examine qualities of the social networks formed in a community‐based healthy lifestyle intervention aimed at reducing excessive maternal weight gain during pregnancy. Participants were randomized into a control group and an intervention group. The latter received a healthy lifestyle curriculum within consistent cohorts of 8–10 participants, and specially designed activities to facilitate formation of new social relations among intervention cohort members.

Our objective was to examine (1) whether participating in a weekly group‐level intervention for 12 weeks resulted in new social ties; and (2) whether women made selective ties according to health behaviors or health status. We hypothesized that (1) participants with more frequent participation in intervention group sessions would have significantly more social ties at the end of the intervention compared to those with less frequent attendance; and (2) women with similar prepregnancy weight status and regularity of physical activity during pregnancy would be more likely to befriend each other during the trial.

Methods

This community‐engaged research project (called Madre Sana, Bebé Sano/Healthy Mother, Healthy Baby) was conducted in collaboration with the Nashville Parks and Recreation Department. The Institutional Review Boards at Vanderbilt University and Wake Forest School of Medicine approved the study protocol. Participants were enrolled between January and March 2011. Written consent/assent forms (Spanish/English) were used.

Inclusion criteria

Women were included if they were (1) >10 and <28 weeks pregnant, (2) ≥16 years old, (3) in prenatal care, (4) Spanish‐ or English‐speaking, (5) expecting to remain in Middle Tennessee for their entire pregnancy, and (6) willing to sign a medical information release form so that we could abstract data from their obstetric and pediatric medical records.

Randomization

This study examines those participants randomly allocated to the intervention arm of a randomized controlled trial22 described elsewhere.

Intervention

Women were randomly assigned to a group (of 8–10) that met at a local community center operated by the Department of Parks and Recreation. The intervention consisted of 12 weekly 90‐minute group sessions. Grounded in social learning theory (SLT), the curriculum aimed to build the core competencies necessary to modify physical activity, nutrition, and sleep behaviors. SLT focuses on learning that occurs within a social context, based on the premise that behavior is learned primarily by observing and imitating others’ behaviors and the associated rewards and punishments. The intervention aimed to create a social learning environment, in which participants could explore new ways of thinking about their health, practice health skills, and acquire positive attitudes about health by modeling with one another.23, 24

Integrated within our intervention were activities to intentionally facilitate new social networks. For example, each group was facilitated by the same leader and met as a consistent group throughout the study. At each session, participants engaged in small‐group activities (two to four people per group). Participants worked toward a common goals (e.g., planning an event for family and friends). Leadership roles were rotated through the group to increase perceptions of group cohesion.25 At each session, the facilitator intentionally reenforced the group's identity as a support network for improving health. Each session included practicing social skills necessary for building and strengthening positive support among family and friends for healthy living (e.g., identifying the sources and types of support for prenatal health that participants currently had, identifying gaps in their support networks, articulating the benefits and attributes of supportive relationships, practicing how to build new and tend to supportive relationships).

Control condition

All participants received the control intervention; only those assigned to the intervention group also received the healthy lifestyle intervention. The control intervention was an infant injury prevention intervention using the best‐practice based “A New Beginning” curriculum. The curriculum was delivered in three 30‐minute home visits with educational material and instruction in either English or Spanish.26 The control intervention was offered to provide value to study participants and aid in retention. To avoid relationship building, each home visit was conducted in each participant's home by a different study team member and totaled 90 minutes of interaction time (compared to the 1,080 minutes of interaction time intervention group members received).

Measures

At two points in the study (week 6 and week 12) participants were asked to complete social network surveys. These surveys asked respondents to name everyone she knew who was participating in the Madre Sana program. Participants were also asked to identify any program participants whom they had known prior to the start of the program, including any relatives. Participants were also asked to name those program participants with whom they had spoken about their pregnancy or pregnancy‐related health behaviors. The key social relation of interest within this study was operationalized as participants who reported having conversations on those two topics with one another. Details are given in the Dependent network variable section below. Name generators such as these are commonly used in social network research and have predictive validity.27 Social networks of individuals with whom one discusses “health matters” are predictive of a wide range of health and health services‐related outcomes. In contrast, social networks of individuals with whom one discusses “important matters” have not been shown to predict health outcomes.27 In addition, health information gathered from each participant included measured height, self‐reported prepregnancy weight, expected delivery date, self‐reported activity level,28 and receipt of WIC assistance. Finally, attendance at intervention sessions was recorded for those assigned to the intervention condition.

Social network data analysis

Social network data were assessed by cross‐sectional descriptive analysis in UCINET29 and exponential random graph (ERG)30, 31 modeling using the “statnet” package32, 33 within the R statistical computing environment.34 ERG models allow hypothesis testing of factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of tie formation between the members of a given dyad. Parameter estimates represent changes in the log‐odds of tie formation as in standard logistic regression.32 The use of ERG methods among social network methodologists has increased markedly in recent years, largely due to the fact that ERG properly accounts for the statistical nonindependence between cases common in social networks, whereas such dependencies within a generalized linear model framework represent a violation of model assumptions, leading to biased results. Positive and statistically significant parameter estimates within the ERG models below will indicate factors that increase the likelihood of a given pair of individuals forming a social tie.

Dependent network variable

The dependent variable for our analysis is operationalized as a social network, determined from a portion of the questionnaire in which respondents were asked to name among the study participants those with whom they “have spoken with about [their] pregnancy, weight, eating healthy, getting enough sleep, or exercise.” Responses from this question were summed for all waves and dichotomized. Thus, dyads within the final dependent network were coded as “1” if they reported having this relation during at any point in the span of the study, and “0” otherwise. Ties within this network were directed, meaning that our dependent variable accounted for the situation where one member of a dyad reported the existence of a relationship, and the other did not.

Network control variables

Two network control variables were created to account for pairs of study participants who knew each other before the study (“knew previously”), and shared a spoken language preference (“share a language”). The age in years of each participant was used to create a matrix describing the absolute value of the difference in ages between each pair of study participants (“difference in age”). Pregnancy‐stage cohort effects were assessed by means of a matrix of values denoting time in days between expected delivery dates for each dyad in the sample (“difference in due date”). Finally, a matrix was created to indicate dyads in which both participants received WIC program assistance (“both WIC recipients”).

Network independent variables

To evaluate Hypothesis 1 (the effectiveness of intervention activities in building new social ties among participants), we created one independent variable “sum of program attendances” to assess the effect of each intervention session attendance on the odds of tie formation. This was operationalized as a matrix, in which each dyad was coded according to the sum of intervention program attendances completed by both persons. A positive and statistically significant parameter estimate for this term would support Hypothesis 1.

To evaluate Hypothesis 2 (the tendency of participants to associate with people with a shared predisposition to engage in (un)healthy behaviors), an additional two independent variables were created to account for the absolute value of differences in body composition (“difference in BMI”) and regularity of reported physical activity (“difference in physical activity level”) at the level of each dyad. Negative and statistically significant parameter estimates for one or both of these model terms indicate support for Hypothesis 2.

ERG analysis

The process of modeling these social network data proceeded in several steps, in order to assess the relative explanatory power of three distinct sets of control and independent variables. The first was a simplified model intended to capture structural regularities observed in social networks across various settings. This initial structural model included terms for the general tendency to form ties within this network (“Edges”), the tendency for an initial tie to be reciprocated (“Mutual”) and the tendency toward triadic closure of the “friend of a friend to become a friend” (“Triadic Closure”). A second model, the “Control Model” was estimated to assess the overall utility of adding the above noted control variables. A final model estimated, the “Full Model,” allows us to interpret the individual parameters related to Hypotheses 1 and 2, as well as assess their effects on the quality of overall model fit. The comparison of model fit between these three models was made using the Aikake Information Criteria (AIC),35 where relatively lower numbers indicate relatively better model fit.

Results

Sample

Of the 135 pregnant women randomized, 116 completed at least one wave of data collection (59 from the intervention and 57 from the control group), resulting in an 86% retention rate over the 12‐week study period. We did not observe differential attrition between study arms. Our social network models included data contributed by the 59 intervention group participants.

Descriptive findings

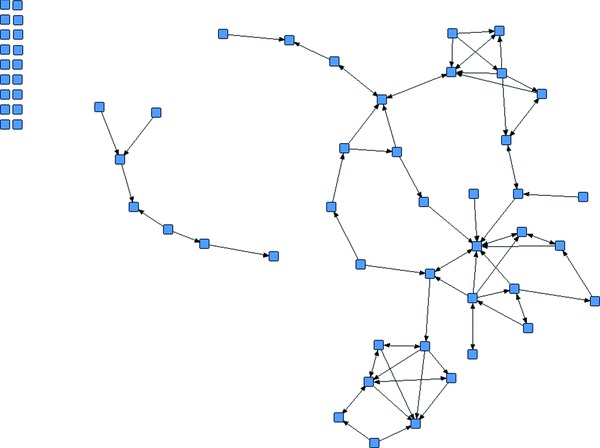

Forty‐one of 59 participants reported forming at least one network tie on the primary relation of interest, sharing information about pregnancy‐related health behavior. Among them, the mean number of ties during the study was 3.56 (SD = 2.11), yielding an overall network density of 2.1%. Among the 41 participants who had formed at least one tie, 49% had one or more reciprocal ties (both members of a dyad noting existence of a tie) (see Figure 1). The network used for this analysis was compiled over two data collection periods; when these two network data collection periods were compared, we found a Jarccard coefficient of similarity1 of 0.04 indicating that only 4% of ties from the initial wave of data collection remained in the same status at the following data collection wave, illustrating that the relations formed within this setting were rather short‐lived. Table 1 provides the mean and standard deviation of several individual‐level variables included in our ERG model analysis. Table 2 describes the mean, standard deviation, and network density for several control variables used in the ERG model analysis.

Figure 1.

Network of supportive social ties formed among 59 study participants.

Note: Eighteen nodes displayed at the left of the graph depict those participants who formed no new social support ties during the course of the study.

Table 1.

Individual‐level variable descriptive statistics

| Mean (std. dev.) | |

|---|---|

| Program attendances (TX group) | 4.63 (3.84) |

| Age | 30.55 (5.88) |

| Physical activity level | 0.74 (0.38) |

Table 2.

Dyadic‐level variable descriptive statistics

| Density | Degree: mean (std. dev.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Support relations | 2.13% | 2.00 (1.84) |

| Knew previously | 0.32% | 0.31 (0.59) |

| Share a spoken language | 65.57% | 37.63 (12.07) |

| Difference in due date | N/A | 56.60 (40.30) |

ERG model findings

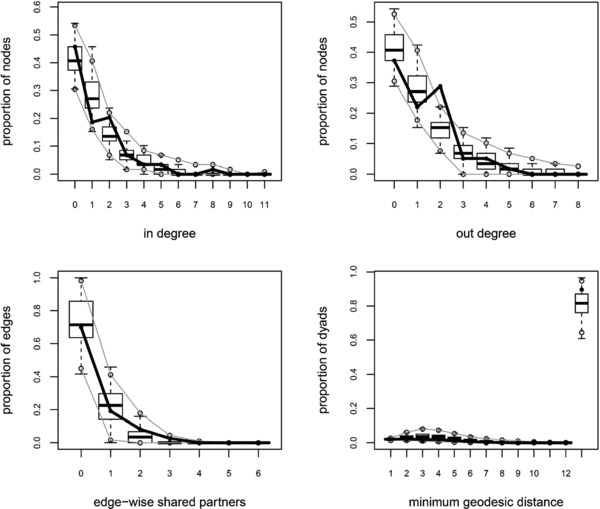

ERG model parameter estimates and standard errors are given in Table 3. As described above, our ERG analysis proceeded in three steps in order to assess the improvements in model fit afforded by each set of parameters included in the full model. The AIC consistently improved across the three iterations of our model, indicating the utility of each parameter set in predicting the likelihood of tie formation in this network. Figure 2 provides a positive assessment of fit between our ERG model parameters and observed data. The 95% confidence intervals (given by box plots and dotted lines) contained in nearly all cases the observed distribution of four key network analytic descriptive measures (given by the bold line in each plot).

Table 3.

ERG model parameter estimates: log‐likelihood of forming supportive relations within a health behavior intervention program

| Structural model β (SE) | Control model β (SE) | Full model β (SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network structural effects | Edges | −4.50 (0.14)*** | −5.59 (0.64)*** | −6.15 (0.66)*** |

| Mutual | 3.15 (0.46)*** | 2.57 (0.47)*** | 2.46 (0.47)*** | |

| Triadic closure | 1.14 (0.18)*** | 0.88 (0.18)*** | 0.65(0.19)*** | |

| Knew previously | 3.73 (0.69)*** | 3.81 (0.71)*** | ||

| Control variables | Share a language | 1.80 (0.85)** | 1.50 (0.60)* | |

| Difference in age | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.02) | ||

| Difference in due date | −0.01 (0.00)** | −0.01 (0.00)** | ||

| Both WIC recipients | 0.36 (0.22) | 0.21 (0.22) | ||

| Difference in BMI | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | ||

| Difference in physical activity level | −1.24 (0.40)*** | −1.14 (0.42)** | ||

| Program effect | Sum of program attendances | 0.09 (0.02)*** | ||

| Model fit | AIC | 616.4 | 547.3 | 530.3 |

Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Several very small nonzero values above are reported as 0.00 after rounding to two decimal places.

Figure 2.

ERG model goodness‐of‐fit diagnostic plots.

In the full model, significant parameters in the hypothesized direction support both of our hypotheses. We find that the intervention activities had a significant and positive effect on the likelihood of tie formation. As the sum of intervention attendances increased among dyads, the likelihood of their forming a tie increased proportionally with the number of sessions attended (β = 0.09, p < 0.001). For example, a pair of participants in this study who both attended four sessions (the average number of sessions), had a 71.6% greater likelihood of forming a new supportive tie (OR = 1.716, p < 0.001) relative to pairs where each member attended just one session. The effect for session attendance was linear and the same for high attenders as well as low attenders.

The significant and negative parameter for “difference in physical activity level” indicates that the more similar two respondents were in terms of their physical activity levels during the study, the more likely they were to form a supportive tie related to program content. This corresponds to a 60% reduction (OR: 0.395, p < 0.05) in the baseline likelihood of tie formation when comparing dyads whose members are completely dissimilar on physical activity (one person reporting being physically active at all data collection times and one never reporting being physically active) to a dyad whose members are completely similar (both always active or both never active). Body mass index was not a significant predictor of tie formation within this network.

In a series of auxiliary regression analyses (not described above) we tested for and did not detect any appreciable effect of these support relations on the main outcome of interest in the broader research project—gestational weight gain. Further research is needed to establish more clearly the reasons for this negative finding.

Discussion

Interpretation of main findings

Throughout this study, we facilitated the formation of supportive social ties related to the health intervention programming provided. The fact that about half of our study participants had at least one such relation is encouraging, as is the fact that increased attendance at intervention sessions was strongly predictive of tie formation. Tempering these encouraging findings is our observation that ties among study participants tended not to be sustained across the 6‐week period between data collection waves, and were quite often unreciprocated. Thus, in terms of creating sustainable peer support networks for expecting mothers to adopt more healthy behaviors during pregnancy, our program achieved only modest success.

The lack of detectable effects on health behavior might be attributable to the relations in question. Set against context of an ever‐growing body of work linking one's own health behaviors to those of their friends and family, these findings suggest that relations formed within an intervention setting (and potentially other group settings) may not be comparable to friend and kinship relations usually addressed in the literature on social networks and health. Specifically, the type or quality of relationships formed through weekly session attendance may not be strong enough to (1) bring about complex behavior change (such as lifestyle changes) or (2) reinforce behavior throughout the new network.

A second possibility is that while social relations are influential for some kinds of health behaviors and outcomes, gestational weight gain is perhaps driven more strongly by factors outside of one's new or existing social networks. Other factors that might explain our results include lack of statistical power; the need for a stronger “treatment dose” (e.g., increased session attendance, more frequent or longer exposure to the group, increased team building early on); the unknown time lag between tie formation and behavior change; and/or measurement issues (e.g., frequency, time span, tool, categorical outcome).

Future research

Our findings motivate two critical questions for future research. First, does the program in question reliably lead to the formation of new social relations among participants? In preparation for the present study, we conducted an extensive literature search; we found no peer‐reviewed work describing detailed social network analyses in intervention settings.36 This is not due to any shortage of health behavior intervention programs that work to foster supportive social relations among program participants (e.g., group prenatal care within healthcare institutions across the United States).17 To the extent that social support and the formation of new social relations is an important aspect of these programs, we propose that program designers, evaluators, and researchers should conduct more work to establish the nature of relations formed within these settings, and their mediating effects on program outcomes.

A more fundamental question raised by this research relates to the viability of achieving changes in individuals’ health behaviors through the development of new social networks (rather than changing the structure or functioning of existing networks). To date, the emerging literature on health and social networks has almost entirely used naturally arising social friendship or kinship networks. Can relations formed within a program change health outcomes? If the answer to this question is yes, it will be important to better understand the magnitude or longevity of such changes, which health issues are amenable to such approaches, and the qualities of individuals (and network structures) that predict whether such an approach leads to improved health outcomes.

Conclusion

In this study, we sought to better understand the qualities of relations formed within a health intervention program setting designed to moderate gestational weight gain within a sample of Latina and African American women at risk of excessive weight gain. Previous research suggested that social relations are a potentially effective means by which to spread health information and healthful behaviors.12 However, we know little about the potential for group interventions to intentionally leverage social networks to change health behaviors. While our analyses did bear out the effectiveness of the intervention program activities in facilitating the formation of new relationships related to program content, these relations remained relatively rare, mostly unreciprocated, and very short‐lived in nearly all cases. Not surprisingly, given the nature of these new relations, we were unable to attribute changes in health behaviors or outcomes to these newly formed relations. For intervention developers it will be useful to know that the likelihood of participants forming a tie increased by 70% with each additional session attended.

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Both authors made substantial contributions to study conception and design, interpretation of data, and writing the manuscript. ET wrote the network analysis program and analyzed the data. SG supervised the research group and data collection. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding Sources

The project described was supported by Project Diabetes Grant (Contract # GR‐11‐34418) from the State of Tennessee (Gesell); and Award Number K23HD064700 (Gesell) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. Award Number UL1TRR24975, which is now UL1TR000445 at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences supported the REDCap database.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Project Diabetes Grant (Contract # GR‐11‐34418) from the State of Tennessee (Gesell); and Award Number K23HD064700 (Gesell) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. Award Number UL1TRR24975, which is now UL1TR000445 at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences supported the REDCap database. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The authors thank Karen Potvin Klein, MA, ELS (Translational Science Institute, Wake Forest University Health Sciences) for her editorial comments. ET analyzed the data and generated the figures. Both authors were involved in interpreting the analyses, writing the paper, and had final approval of the submitted version.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01279109

Footnotes

The Jaccard coefficient ranges from 1 in the case where all existing ties persist from one wave to another and no new ties are added, to 0 in the case where no ties are held in common across both waves of network data.

References

- 1. Mercken L, Snijders TAB, Steglich C, Vartiainen E, de Vries H. Dynamics of adolescent friendship networks and smoking behavior. Soc Netw. 2010; 32(1): 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mercken L, Snijders TAB, Steglich C, de Vries H. Dynamics of adolescent friendship networks and smoking behavior: social network analyses in six European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 69(10): 1506–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steglich C, Sinclair P, Holliday J, Moore L. Actor‐based analysis of peer influence in A Stop Smoking In Schools Trial (ASSIST). Soc Netw. 2012; 34(3): 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knecht A, Burk W, Weesie J, Steglich C. Friendship and alcohol use in early adolescence: a multilevel social network approach. J Res Adolesc. 2011; 21(2): 475–487. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiuru N, Burk WJ, Laursen B, Salmela‐Aro K, Nurmi JE. Pressure to drink but not to smoke: disentangling selection and socialization in adolescent peer networks and peer groups. J Adolesc. 2010; 33(6): 801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de la Haye K, Robins G, Mohr P, Wilson C. Obesity‐related behaviors in adolescent friendship networks. Soc Netw. 2010; 32(3): 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shoham DA, Tong L, Lamberson PJ, Auchincloss AH, Zhang J, Dugas L, Kaufman JS, Cooper RS, Luke A. An actor‐based model of social network influence on adolescent body size, screen time, and playing sports. PLoS One 2012; 7(6): e39795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gesell SB, Tesdahl E, Ruchman E. The distribution of physical activity in an after‐school friendship network. Pediatrics 2012; 129(6): 1064–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simpkins SD, Schaefer DR, Price CD, Vest AE. Adolescent friendships, BMI, and physical activity: untangling selection and influence through longitudinal social network analysis. J Res Adolesc. 2013; 23(3), 537–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(4): 370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Valente TW, Fujimoto K, Chou CP, Spruijt‐Metz D. Adolescent affiliations and adiposity: a social network analysis of friendships and obesity. J Adolesc Health 2009; 45(2): 202–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Valente TW. Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valente TW. Network interventions. Science 2012; 337(6090): 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, Magriples U, Massey Z, Reynolds H, Rising SS. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 110(2 Pt 1): 330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tandon SD, Colon L, Vega P, Murphy J, Alonso A. Birth outcomes associated with receipt of group prenatal care among low‐income Hispanic women. J Midwifery Women's Health 2012; 57(5): 476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Massey Z, Rising SS, Ickovics J. CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care: promoting relationship‐centered care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006; 35(2): 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanner‐Smith EE, Steinka‐Fry KT, Gesell SB. Comparative effectiveness of group and individual prenatal care on gestational weight gain. Matern Child Health J. 2014; 18(7): 1711–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baldwin KA. Comparison of selected outcomes of CenteringPregnancy versus traditional prenatal care. J Midwifery Women's Health 2006; 51(4): 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feldman PJ, Dunkel‐Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosom Med. 2000; 62(5): 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of premature birth. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339(5): 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oakley A. Social support in pregnancy: the “soft” way to increase birthweight? Soc Sci Med. 1985; 21(11): 1259–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gesell SB, Katula JA, Strickland C, Vitolins M. Feasibility and initial efficacy evaluation of a community‐based cognitive‐behavioral lifestyle intervention to prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy in Latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2015; 19(8): 1842–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McTighe J, Wiggins G. Understanding by Design: Professional Development Workbook. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vella J. Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salo M. The Relation Between Sociometric Choices and Group Cohesion. In Technical Report 1193. Arlington, VA: US Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, Force Stabilization Research Unit; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moran DE, Kallam GB. A New Beginning: Your Personal Guide to Postpartum Care. Arlington, TX: Customized Communications, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perry BL, Pescosolido BA. Functional specificity in discussion networks: the influence of general and problem‐specific networks on health outcomes. Soc Netw. 2010; 32(4): 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Published September 29, 2014. Accessed December 30, 2014.

- 29. Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robins GL, Snijders TAB, Wang P, Handcock MS, Pattison PE. Recent developments in exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc Netw. 2007; 29(2): 192–215. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Snijders TAB, Pattison PE, Robins GL, Handcock MS. New specifications for exponential random graph models. Sociol Methodol. 2006; 36(1): 99–153. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goodreau SM, Handcock MS, Hunter DR, Butts CT, Morris M. A statnet tutorial. J Stat Softw. 2008; 24(9): 1–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Handcock MS, Hunter DR, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, Morris M. Statnet: software tools for the representation, visualization, analysis and simulation of network data. J Stat Softw. 2008; 24(1): 1548–7660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. The R Core Team: R . A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

- 35. Akaike H. Likelihood of a model and information criteria. J Econ. 1981; 16: 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gesell SB, Bess KD, Barkin SL. Understanding the social networks that form within the context of an obesity prevention intervention. J Obes. 2012; 2012: 749832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]