Abstract

Purpose

Evolving therapies have improved the prognoses of patients with breast cancer; and currently, the number of long-term survivors is continuously increasing. However, these patients are at increased risk of developing a second cancer. Thus, late side effects are becoming an important issue. In this study, we aimed to investigate whether patient and tumor characteristics, and treatment type correlate with secondary tumor risk.

Methods

This case-control study included 305 patients with a diagnosed second malignancy after almost 6 months after the diagnosis of primary breast cancer and 1,525 controls (ratio 1:5 of cases to controls) from a population-based cohort of 6,325 women. The control patients were randomly selected from the cohort and matched to the cases according to age at diagnosis, calendar period of diagnosis, disease stage, and time of follow-up.

Results

BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)+ status, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy were related to increased risk of developing a second cancer, whereas hormonotherapy showed a protective effect. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and estrogenic receptor level <10% increased the risk of controlateral breast cancer. HER2+ status increased the risk of digestive system and thyroid tumors, while BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation increased the risk of cancer in the genital system.

Conclusion

Breast cancer survivors are exposed to an excess of risk of developing a second primary cancer. The development of excess of malignancies may be related either to patient and tumor characteristics, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and HER2+ status, or to treatments factors.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Case-control studies, Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, Second primary neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

In developed countries, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women [1]. Survival outcomes have improved with early, frequent screening assessments, advances in surgery and radiotherapy, evolving hormone therapy (HT), and improved chemoimmunotherapy. In the literature, the relative survival of women with breast cancer in Europe is reported to be 81.9% at 5 years, over the period 1999-2007 [2].

Currently, many women with breast cancer have become long-term survivors. Thus, the risk of developing second malignant neoplasms (SMNs) has become an important concern for patients, their families, and clinicians. Most population-based studies have shown an overall higher risk of second neoplasms in breast cancer survivors than in the general population [3,4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, an increased incidence of cancer has been observed in different sites, including the contralateral breast, ovary, endometrium, thyroid gland, lung, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, leukemia, stomach, and colon [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. The increased risk of developing a second cancer may be related to tumor characteristics [16], therapy approach [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18], or genetic factors [19,20].

In the present study, we performed a nested case-control study in a population-based cohort to analyze a large, homogeneous cohort of women with breast cancer. We tested the correlations of the risk of developing a second tumor to patient and tumor characteristics at the diagnosis of primary breast cancer and therapeutic approach utilized, based on data recorded in the Modena Cancer Registry (MCR).

METHODS

This study had a case-control design, nested within a population-based cohort of 6,325 women with a primary, nonmetastatic breast cancer. The women were diagnosed between January 1996 and December 2007. The patients were registered in the MCR, according to the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Revision (ICD-O3). Different ICD classifications were used during the period 1996-2007. Therefore, we converted all cancer codes into ICD-O3 terms. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) tumor, neoplasm, metastasis (TNM) classification of malignant tumors (sixth edition) were used for staging the disease. Clinical and medical record information, including treatment modalities, and tumor characteristics, were converted into a standardized electronic form.

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: a diagnosis of primary nonmetastatic breast cancer histologically confirmed between January 1996 and December 2007, female sex, complete information on disease stage and treatment modalities, and survival for 6 or more months without the development of a SMN. Patients were considered to have SMNs when second tumors were diagnosed at least 6 months after the first primary diagnosis and recorded as code/3 (malignant, primary site) according to the ICD-O3. The SMNs were considered microscopically verified when diagnosis was based on malignant histologic or cytologic reports, and were classified according to the ICD-O3 terms.

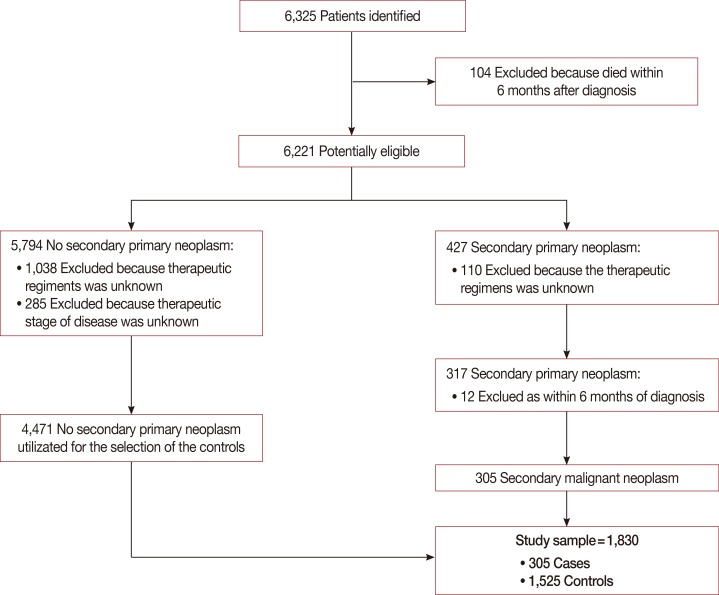

Among 6,325 patients with primary, nonmetastatic breast cancer, 104 were excluded because they died within 6 months of the breast cancer diagnosis, 1,148 were excluded because the therapeutic regimens were not reported in the electronic form, and 285 were excluded because the stage of disease was unknown. Of the remaining 4,788 patients, 4,471 did not develop SMNs and 317 were diagnosed with a SMN during follow-up. Of the 317 patients, 12 were excluded because they developed a second cancer within 6 months of the diagnosis. In conclusion, we identified 305 cases of second cancers after the diagnosis of a primary breast cancer that met the study criteria (Figure 1). A detailed list of second cancers is provided in Supplementary Table 1 (available online).

Figure 1. Flow-chart of patients included in the analysis, starting from 6,325 women with primary breast cancer recorded by Modena Cancer Registry between 1996 and 2007.

The SMNs were classified as head and neck cancer, melanoma, skin cancer (nonmelanoma), lung cancer (lung, bronchus, and trachea), cancer of the digestive system (esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, liver, and pancreas), cancer of the genital system (cervix and corpus uteri, ovary, and other female genital organs), cancer of the urinary system (kidney and bladder), thyroid cancer, hematological malignancies (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, leukemia [acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acute and chronic myeloid leukemia, and acute monocytic leukemia], myeloma, and myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic syndrome), contralateral breast cancer, and other cancers (mesothelioma; soft tissue neoplasia, including the heart, other endocrine glands, and thymus, and miscellaneous or unspecified neoplasia) (Table 1). We conducted a nested case-control study in a population-based cohort by using risk-set sampling, with the follow-up in months as timescale and a case-control ratio of 1:5. Thus, for 305 cases, 1,525 control patients were randomly selected from the cohort and matched to the cases according to age at diagnosis of breast cancer (four age groups: <50, 50-59, 60-69, and ≥70 years), calendar period of diagnosis (1996-1998,1999-2001, 2002-2004, and 2005-2007), and breast cancer stage (I-IIb and IIIa-IV). The follow-up duration was calculated in months from the diagnosis of primary breast cancer to the date of diagnosis of SMNs or to the date of last checkup. The characteristics of the 305 cases and 1,525 controls are presented in Table 2. The MCR covered an average population of 643,125 habitants in the province of Modena between 1996 and 2007, of whom 51.1% were female.

Table 1. Number of secondary malignancies observed between 1996 and 2007 after primary breast cancer and cumulative incidence by Gooley method.

| Cancer type | No. | Cumulative incidence at 8 yr (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contralateral breast cancer | 69 | 1.64 | 1.24-2.12 |

| Digestive system* | 55 | 1.17 | 0.86-1.55 |

| Nonmelanoma skin | 46 | 1.16 | 0.84-1.57 |

| Genital system† | 42 | 0.98 | 0.69-1.37 |

| Urinary system‡ | 16 | 0.43 | 0.25-0.71 |

| Lung | 15 | 0.31 | 0.17-0.52 |

| Thyroid | 11 | 0.28 | 0.15-0.50 |

| Melanoma | 7 | 0.21 | 0.09-0.43 |

| Head and neck | 6 | 0.19 | 0.08-0.43 |

| Other§ | 9 | 1.77 | 1.36-2.28 |

| Solid cancer (excluding contralateral breast cancer) | 207 | 4.96 | 4.27-5.28 |

| Hematological malignanciesII | 29 | 0.65 | 0.43-0.96 |

| Total | 305 | 7.27 | 6.42-8.18 |

Data from 4,776 cases selected from 6,325 women recorded by Modena Cancer Registry between 1996 and 2007.

CI=confidence interval.

*Digestive system: esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, liver and pancreas; †Genital system: cervix and corpus uteri, ovary, other female genital organs; ‡Urinary system: kidney and bladder; §Other: mesothelioma; soft tissue neoplasia, including heart, other endocrine, and thymus; and miscellaneous or unspecified neoplasia; ∥Hematological malignancies: Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acute and chronic myeloid leukemia, acute monocytic leukemia, myeloma, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic syndrome.

Table 2. Overall risk of second cancer, adjusted by age and calendar year at diagnosis, by tumor and patients characteristics, and by therapeutic approach, using risk set sampling.

| Case* (n=305) No. (%) |

Control* (n=1,525) No. (%) |

OR (95% CI) | p-value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour and patients characteristics | |||||

| Grading | 1-2 | 184 (62) | 968 (66) | 1.00 | |

| 3 | 112 (38) | 500 (34) | 1.21 (0.92-1.59) | 0.174 | |

| Unknown | 9 (3) | 57 (4) | 0.83 (0.42-1.67) | 0.610 | |

| Primary tumor size (T) | T1mic-T1b | 101 (35) | 471 (32) | 1.00 | |

| T1c | 119 (41) | 646 (44) | 0.87 (0.65-1.17) | 0.349 | |

| T2 | 71 (24) | 353 (24) | 0.93 (0.65-1.34) | 0.702 | |

| Unknown | 14 (5) | 55 (4) | 1.26 (0.64-2.44) | 0.503 | |

| ER (%) | ≥ 10 | 233 (80) | 1,212 (82) | 1.00 | |

| < 10 | 62 (20) | 269 (18) | 1.19 (0.88-1.62) | 0.262 | |

| Unknown | 10 (3) | 44 (3) | 1.15 (0.56-2.38) | 0.702 | |

| PR (%) | ≥ 10 | 193 (66) | 954 (65) | 1.00 | |

| < 10 | 101 (34) | 524 (35) | 0.95 (0.73-1.24) | 0.698 | |

| Unknown | 11 (4) | 47 (3) | 1.13 (0.56-2.87) | 0.732 | |

| Ki-67 (%) | < 20 | 185 (63) | 969 (66) | 1.00 | |

| ≥ 20 | 108 (37) | 488 (34) | 1.16 (0.90-1.50) | 0.261 | |

| Unknown | 12 (4) | 68 (5) | 0.92 (0.48-1.74) | 0.793 | |

| HER2‡ | Negative | 115 (78) | 633 (86) | 1.00 | |

| Positive | 32 (22) | 102 (14) | 1.73 (1.10-2.70) | 0.017 | |

| Unknown | 158 (52) | 790 (52) | 1.01 (0.65-1.58) | 0.957 | |

| Genetic predisposition | Sporadic | 277 (91) | 1,403 (93) | 1.00 | |

| Fam. | 19 (6) | 95 (6) | 1.04 (0.62-1.73) | 0.889 | |

| Inher. | 7 (2) | 12 (1) | 3.53 (1.29-9.64) | 0.014 | |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 15 (1) | 0.69 (0.17-2.82) | 0.601 | |

| Therapeutic approach (mutually exclusive) | |||||

| Surgery alone | No | 277 (91) | 1,409 (91) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 28 (9) | 116 (9) | 1.19 (0.76-1.86) | 0.440 | |

| Surgery+CHT | No | 283 (93) | 1,459 (96) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 22 (7) | 66 (4) | 1.76 (1.07-2.91) | 0.026 | |

| Surgery+RT | No | 268 (88) | 1,388 (91) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 37 (12) | 137 (9) | 1.44 (0.96-2.16) | 0.078 | |

| Surgery+CHT+RT | No | 281 (92) | 1,423 (93) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 24 (8) | 102 (7) | 1.20 (0.74-1.95) | 0.464 | |

| Surgery+HT | No | 258 (85) | 1,272 (83) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 47 (15) | 253 (17) | 0.88 (0.61-1.27) | 0.494 | |

| Surgery+RT+HT | No | 227 (74) | 1,127 (74) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 78 (26) | 398 (26) | 0.98 (0.73-1.31) | 0.878 | |

| Surgery+CHT+HT | No | 282 (92) | 1,375 (90) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 23 (8) | 150 (10) | 0.74 (0.47-1.16) | 0.188 | |

| Surgery+CHT+RT+HT | No | 259 (85) | 1,224 (80) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 46 (15) | 301 (20) | 0.72 (0.50-1.03) | 0.074 | |

| Surgery +/-CHT+/-RT+HT | No | 111 (36) | 423 (28) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 194 (64) | 1,102 (72) | 0.66 (0.50-0.86) | 0.003 | |

| Therapeutic approach | |||||

| Surgery+HT+CHT+/-RT | 69 (23) | 451 (30) | 1.00 | ||

| Surgery alone/Surgery+HT+/-RT | 153 (50) | 769 (50) | 1.30 (0.93-1.83) | 0.125 | |

| Surgery+RT | 37 (12) | 137 (9) | 1.85 (1.15-2.98) | 0.011 | |

| Surgery+CHT | 22 (7) | 66 (4) | 2.24 (1.30-3.85) | 0.004 | |

| Surgery+CHT+RT | 24 (8) | 102 (7) | 1.58 (0.93-2.70) | 0.093 |

OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; ER=estrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor; Fam.=familial; the woman have at least two first-degree relatives (mother, father, daughter, son, sister, brother) with breast cancer; Inher.=inheritance; mutation of breast cancer gene (BRCA1 or BRCA2); CHT=chemotherapy; RT=radiotherapy; HT=hormone therapy.

*Case control 1:5 matched by age group, stage, year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer, using risk set sampling; Multiple conditional logistic regression where the factors were adjusted by age and calendar year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer; †p-value were two-sided Wald test; ‡HER2 evaluation was routinely performed from 2001.

Statistical analysis

For estimating cumulative incidences, follow-up calculations were started at the date of primary breast cancer diagnosis and ended at the date of SMN diagnosis or the date of death or last follow-up (December 31, 2009). Cumulative incidences were estimated with the Gooley method for competing risk, and death from any cause was considered a competing event [21]. Cumulative incidences were compared by using the regression modeling proposed by Fine and Gray [22]. The main outcomes were measured by using the conditional logistic regression performed to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of the odds ratios (ORs) for associations between SMNs and the therapeutic procedure and other risk factors [23]. In parallel to the case-control study for all second cancer cases, we also conducted a case-control study for the different SMN groups (described above) with the same data extraction forms and procedures. The roles of the therapeutic modalities were analyzed by using the following two approaches: (1) comparing each individual modality to everything else as reference group and (2) considering as reference group (chosen as the lowest-risk group to develop SMNs) the patients treated with HT and chemotherapy after surgery with or without radiotherapy, and as comparison groups (a) the patients treated only surgically or with HT with or without radiotherapy after surgery, (b) those treated with radiotherapy after surgery, (c) those treated with chemotherapy after surgery, and (d) those treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy after surgery.

Furthermore, we conducted an ancillary case-control study to investigate the relationship between human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) receptor expression and a single group of second cancers. All analyses were performed by adjusting the factor or exposure of interest with age and calendar year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer as continuous covariates. A comparison between categorical variables was performed with the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, whichever was appropriate. Continuous covariates were analyzed with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The ORs and confidence intervals set at 95% (95% CI) were determined. All the analyses were performed with the Stata/SE 10.0 package (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

In the Modena Cancer Registry, from January 1996 to December 2007, 6,325 women with primary, nonmetastatic breast cancer were registered in accordance with the ICD-03/3 classification. For the whole population, the median age at breast cancer diagnosis was 61 years (range, 22-96 years). Figure 1 shows the selection procedure that led to the final cohort of patients. In the selected cohort of 4,776 patients, the median follow-up period was 6.3 years (range, 1-14 years), which corresponded to 30,304 person-years of observation. In the 4,776 eligible patients, the 8-year cumulative incidence of secondary cancer was 7.3% (95% CI, 6.4-8.2) (Table 1). The median age of the 1,830 patients (305 case and 1,525 controls) was 64 years at diagnosis of breast cancer. Overall, second cancers were diagnosed less than 3 years after the primary breast cancer was diagnosed in 40% of the cases. In detail, more than 50% of the cases of lung, genital and urinary system, thyroid, and lymphoma second cancers were diagnosed within 3 years after the diagnosis of the primary breast cancer. About 8% of the cases and controls underwent surgery alone. The remaining study population were treated with radiotherapy (RT) and/or chemotherapy (CHT) and/or HT after surgery. However, the therapeutic approach changed during the period of 1996-2007. The frequency of RT alone after surgery declined from 14% to 3% from the period 1996-1998 to the period 2005-2007 (p<0.001). Over the same period, the frequency of HT, alone or in combination with RT and/or CHT, increased from 62% to 84% (p<0.001). In particular, the frequency of HT in combination with RT after surgery increased from 17% in the period 1996-1998 to 43% in the period 2005-2007 (p<0.001). The frequency of CHT, alone or in combination with RT and/or HT, decreased from 46% to 32% from the period 1996-1998 to the period 2005-2007 (p<0.001). Furthermore, the frequency of combination treatment with CHT and RT decreased during the study period (p=0.029). Of the patients treated with CHT alone or in combination with RT and/or HT, 66% received regimens containing cyclophosphamide.

Over the study period, of the 305 patients, 9% were treated with surgery alone; 12%, with RT alone; 7%, with CHT alone; and 15%, with HT alone, whereas 57% were treated with CHT in combination with RT and/or HT. The details of the characteristics of the 305 cases and 1,525 matched controls are reported in Supplementary Table 2 (available online).

The 1,148 patients excluded because the therapeutic regimens were not reported in the electronic form showed a cumulative incidence of second neoplasia of 7.4% at 8 years, similar to the 7.3% observed in the 4,776 eligible patients (p=0.499). Furthermore, after adjusting for age, stage, and year of diagnosis, no significant differences were found between the patients excluded and those included in the study (p=0.300).

Overall risk of a second malignancy

Risk of a second cancer related to tumor and patient characteristics

We found that the risk of SMNs was not affected by the size and grading of the primary tumor, the estrogen or progesterone receptor status, or the proliferation marker, Ki-67 (Table 2). Only BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and HER2 receptor positivity were related to a higher risk of developing SMNs than that of the control group, with ORs of 3.53 (95% CI, 1.29-9.64) and 1.73 (95% CI, 1.10-2.70), respectively.

Risk of a second cancer related to treatment modalities

The patients treated with CHT alone showed a higher risk of developing a second cancer (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.07-2.91) (Table 2) than those treated with other modalities. The patients treated with RT showed a moderate increase in risk (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 0.96-2.16). The patients treated with the combination of CHT and RT showed a moderate increase in risk, but it was not statistically significant (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.74-1.95). Treatment with HT tended to reduce the risk of a second cancer when used in combination with CHT (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.47-1.16) and RT plus CHT (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.50-1.03). By contrast, treatment after surgery with HT alone or HT and RT showed a risk of a second cancer comparable that with other modalities (OR, 95% CI: 0.88, 0.61-1.27 and 0.98, 0.73-1.31, respectively). Based on these results, we divided the therapeutic approaches into five groups, as described in the Statistical analysis section. With the group treated with HT plus CHT and/or RT after surgery as reference, we observed an excess of risk in the patients treated after surgery with CHT alone (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.30-3.85) and RT alone (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.15-2.98) and a marginal risk in those treated with the combination of RT and CHT (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 0.93-2.70).

Site-specific cancer risk

Because the number of secondary cancer cases was low, we grouped the cases according to the site of occurrence (Table 3). Chemotherapy, RT, and CHT plus RT induced an increased risk of contralateral breast cancer, with ORs of 3.50 (95% CI, 1.31-9.31), 7.82 (95% CI, 2.43-25.1), and 4.11 (95% CI, 1.44-11.7), respectively. In addition, low estrogen receptor expression level (<10%) augmented the risk of contralateral breast cancer (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.01-3.56). Positive HER2 receptor expression was associated with a high risk of digestive system cancer (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 1.36-9.79). The BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation determined an augmented risk of genital system cancer (OR, 14.9; 95% CI, 2.06-108). Considering other site-specific cancers, we observed that HER2 receptor positivity was only marginally related to a high risk of thyroid tumor (OR, 9.70; 95% CI, 0.70-135; p=0.090) and tumor of the genital system (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 0.83-11.7; p=0.092) (Table 4).

Table 3. Risk of specific second cancer by therapeutic approach and tumor and patients characteristics*.

| Digestive system† (n = 55) OR (95% CI) |

Genital system‡ (n = 42) OR (95% CI) |

Contralateral BC (n = 69) OR (95% CI) |

Lung (n = 15) OR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery+HT+CHT+/-RT | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Surgery/Surgery+HT+/-RT | 1.55 (0.66-3.66) | 1.66 (0.55-4.96) | 1.53 (0.70-3.34) | 1.19 (0.30-4.79) |

| Surgery+RT | 2.86 (0.79-10.3) | 2.37 (0.62-90.7) | 3.50 (1.31-9.31) | 5.65 (0.76-42.1) |

| Surgery+CHT | 1.86 (0.31-11.0) | 2.91 (0.78-10.8) | 7.82 (2.43-25.1) | 2.43 (0.26-22.3) |

| Surgery+RT+CHT | 0.70 (0.41-7.12) | 0.62 (0.16-5.99) | 4.11 (1.44-11.7) | 0.75 (0.11-4.92) |

| Surgery+/-RT+/-CHT+HT§ | 0.76 (0.38-1.52) | 0.73 (0.34-1.54) | 0.28 (0.16-0.48) | 0.44 (0.12-1.64) |

| ER < 10% | 0.82 (0.32-2.13) | 1.34 (0.55-3.27) | 1.88 (1.01-3.56) | 0.84 (0.22-3.22) |

| PR < 10% | 1.34 (0.71-2.51) | 0.95 (0.45-1.99) | 1.16 (0.69-1.95) | 0.94 (0.34-2.62) |

| Ki-67 ≥ 20% | 1.02 (0.55-1.88) | 1.28 (0.57-2.90) | 1.50 (0.89-2.54) | 0.47 (0.15-1.42) |

| HER2+ | 3.64 (1.36-9.79) | 3.12 (0.83-11.7) | 1.43 (0.50-4.06) | 1.28 (0.09-17.0) |

| Inheritance | 3.37 (0.56-20.3) | 14.9 (2.06-108) | 0.94 (0.13-6.64) | - |

OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; BC=breast cancer; HT=hormone therapy; CHT=chemotherapy; RT=radiotherapy; ER=estrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Inheritance=mutation of breast cancer gene (BRCA1 or BRCA2).

*Case control 1:5 matched by age group, stage, year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer, using risk set sampling; Multiple conditional logistic regression where the factors were adjusted by age and calendar year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer; †Digestive system: esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, liver and pancreas; ‡Genital system: cervix and corpus uteri, ovary, other female genital organs; §Other therapies versus patients treated with hormone therapy with any combination (+/-RT and +/-CHT).

Table 4. Risk of some site specific second cancer related to HER2 status adjusted by age and calendar year at diagnosis of the primary breast cancer*.

| Cases | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 15 | 1.28 | 0.10-17.8 | 0.853 |

| Skin (not melanoma) | 46 | 2.86 | 0.64-12.7 | 0.167 |

| Digestive system† | 55 | 3.64 | 1.36-9.79 | 0.010 |

| Genital system‡ | 42 | 3.12 | 0.83-11.7 | 0.092 |

| Urinary system§ | 16 | 3.60 | 0.12-653 | 0.629 |

| Thyroid | 11 | 9.70 | 0.70-135 | 0.090 |

| Hematological∥ | 29 | 2.22 | 0.17-28.7 | 0.542 |

| Contralateral BC | 69 | 1.43 | 0.50-4.06 | 0.501 |

HER2 =human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; OR =odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; BC=breast cancer.

*Case control 1:5 matched by age group, stage, year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer, using risk set sampling; Multiple conditional logistic regression where the factors were adjusted by age and calendar year of diagnosis of primary breast cancer; †Digestive system: esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, liver and pancreas; ‡Genital system: cervix and corpus uteri, ovary, other female genital organs; §Urinary system: kidney and bladder; ∥Hematological: Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia Hodgkin and, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acute and chronic myeloid leukemia, acute monocytic leukemia, myeloma, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic syndrome.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrated that only some tumor and patient characteristics, including HER2 receptor positivity, low estrogen receptor expression level, and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, had an effect on the risk of SMNs. The major drawbacks of our study were the exclusion of 1,148 patients because the therapeutic regimens were not reported and the possible underpowered analysis in the evaluation of the site-specific cancer risk, possibly because of the wide 95% CI associated in some analyses. Although retrospective studies are inherently limited, our study had the following strengths: it was conducted within a well-defined cohort; controls were selected by random sampling from the overall population, which avoided selection bias; the amount of exposure was recorded before the development of SMNs, which avoided information bias; cases and controls were matched for confounding variables, which allowed the study of many exposure factors (i.e., therapeutic regimens, patient and tumor characteristics, BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, and HER2 status); and our nested case-control study design was optimal for analyzing rare events such as SMNs. Furthermore, to avoid the main drawback of cancer registries, which typically lack data on patient characteristics, treatments, and follow-up, we integrated cancer registry data with information on patient and tumor characteristics and treatment modalities, and other medical data obtained from the analyses of medical records.

As expected, CHT significantly increased the risk of SMNs. Radiotherapy augmented the risk, but the effect was not statistically significant. The combination of CHT and RT did not significantly alter the risk of SMNs. Adding HT to CHT with or without RT tended to reduce the overall risk, but the effect was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, all of the women treated with HT, alone or in combination with CHT and/or RT, showed a decreased risk of developing secondary malignancies (OR, 0.66; p=0.003) and the protective effect of HT. HT is well known to reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer, although some authors [3,4,5] have reported an increased risk of endometrial and ovarian cancers. Nevertheless, our results did not show any effect of HT on the cancers of the genital system. Overall, considering as reference group the patients treated with surgery plus CHT and HT with or without RT, we found an excess of risk of developing a second cancer in the CHT and CHT+RT treatment groups.

Furthermore, our results showed that CHT, RT, and low estrogen receptor expression level increased the risk of contralateral breast cancer. In their study, Bouchardy et al. [16] reported that the risk of contralateral estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer increased after a primary ER-negative breast cancer. Our data also showed an increased risk of contralateral breast cancer, but we did not test the ER status of the second cancer. We also found that HER2 receptor positivity was associated with a high risk of cancer of the digestive system and marginally associated with the risk of developing tumors of the thyroid and genital system, and that inheritance status (BRCA1 or BRCA2) determined an augmented risk of cancer of the genital system. Our result showed an increased, though not statistically significant, risk of lung cancer in patients treated with RT alone after surgery, probably due to the few cases recorded related to the number of factors analyzed. Thus, our result is only partially consistent with the results reported by several other studies [14,15] and may be related to the size of the radiation fields.

An interesting result, although the data were recorded only in about 50% of the cases and controls and then with a probable presence of selection bias, was the relationship between HER2 proteins and secondary tumors. HER2 is a tyrosine kinase receptor that is overexpressed in 25% to 30% of human breast cancers [24]. Overexpression of HER2 protein has been detected in several other human cancers, including ovarian [24], lung [25], thyroid [25,26], and gastric cancers [27]. Overexpression or constitutive activation of HER2 can stimulate many signaling pathways, including mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AK-transforming factors, mammalian target of rapamycin, Src kinase, and STAT transcription factors [28]. These signaling pathways induce cellular proliferation, migration, differentiation, angiogenesis, regulation of apoptosis, and cell cycle control [29,30]. We found that HER2 positivity in patients with breast cancer was associated with increased risk of second tumors in the digestive system and thyroid. We could not definitively explain this augmented risk owing to the lack of reference data from controlled clinical trials with long follow-up observation periods.

In conclusion, this case-control study showed that breast cancer survivors' risk of developing a second cancer was related to patient and tumor characteristics, genetic factors, and therapies received.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Materials

List of secondary primary neoplasms

Characteristics of the 305 women with breast cancer who developed secondary malignant neoplasms and of 1,525 matched controls

References

- 1.Hortobagyi GN, de la Garza Salazar J, Pritchard K, Amadori D, Haidinger R, Hudis CA, et al. The global breast cancer burden: variations in epidemiology and survival. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005;6:391–401. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2005.n.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, et al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE: 5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortesi L, De Matteis E, Rashid I, Cirilli C, Proietto M, Rivasi F, et al. Distribution of second primary malignancies suggests a bidirectional effect between breast and endometrial cancer: a population-based study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1358–1363. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181b9f5d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellemkjaer L, Friis S, Olsen JH, Scélo G, Hemminki K, Tracey E, et al. Risk of second cancer among women with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2285–2292. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellemkjær L, Christensen J, Frederiksen K, Pukkala E, Weiderpass E, Bray F, et al. Risk of primary non-breast cancer after female breast cancer by age at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1784–1792. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubino C, de Vathaire F, Diallo I, Shamsaldin A, Lê MG. Increased risk of second cancers following breast cancer: role of the initial treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;61:183–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1006489918700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molina-Montes E, Requena M, Sánchez-Cantalejo E, Fernández MF, Arroyo-Morales M, Espën J, et al. Risk of second cancers cancer after a first primary breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langballe R, Olsen JH, Andersson M, Mellemkjær L. Risk for second primary non-breast cancer in pre- and postmenopausal women with breast cancer not treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy or endocrine therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:946–952. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beadle G, Baade P, Fritschi L. Acute myeloid leukemia after breast cancer: a population-based comparison with hematological malignancies and other cancers. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:103–109. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vuong NT, Boucher E, Gedouin D, Vauleon E, Le Prise E, Raoul JL. Radiation-induced oesophageal carcinoma after breast carcinoma: a report of five cases including three successfully treated by radiochemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:1184–1186. doi: 10.1080/02841860701338846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karlsson P, Holmberg E, Samuelsson A, Johansson KA, Wallgren A. Soft tissue sarcoma after treatment for breast cancer: a Swedish population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:2068–2075. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kmet LM, Cook LS, Weiss NS, Schwartz SM, White E. Risk factors for colorectal cancer following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;79:143–147. doi: 10.1023/a:1023926401227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Curtis RE, Kry SF, Gilbert E, Lamart S, Berg CD, et al. Proportion of second cancers attributable to radiotherapy treatment in adults: a cohort study in the US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:353–360. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Curtis RE, Gilbert E, Berg CD, Smith SA, Stovall M, et al. Second solid cancers after radiotherapy for breast cancer in SEER cancer registries. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:220–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stovall M, Smith SA, Langholz BM, Boice JD, Jr, Shore RE, Andersson M, et al. Dose to the contralateral breast from radiotherapy and risk of second primary breast cancer in the WECARE study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouchardy C, Benhamou S, Fioretta G, Verkooijen HM, Chappuis PO, Neyroud-Caspar I, et al. Risk of second breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status and family history. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:233–241. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1137-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malone KE, Begg CB, Haile RW, Borg A, Concannon P, Tellhed L, et al. Population-based study of the risk of second primary contralateral breast cancer associated with carrying a mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2404–2410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemminki K, Zhang H, Sundquist J, Lorenzo Bermejo J. Modification of risk for subsequent cancer after female breast cancer by a family history of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntosh A, Shaw C, Evans G, Turnbull N, Bahar N, Barclay M, et al. Clinical Guidelines and Evidence Review for the Classification and Care of Women at Risk of Familial Breast Cancer. London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care/University of Sheffield; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mondi MM, Rich R, Ituarte P, Wong M, Bergman S, Clark OH, et al. HER2 expression in thyroid tumors. Am Surg. 2003;69:1100–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Vol. 1. The Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomizawa K, Suda K, Onozato R, Kosaka T, Endoh H, Sekido Y, et al. Prognostic and predictive implications of HER2/ERBB2/neu gene mutations in lung cancers. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kremser R, Obrist P, Spizzo G, Erler H, Kendler D, Kemmler G, et al. Her2/neu overexpression in differentiated thyroid carcinomas predicts metastatic disease. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:322–328. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jørgensen JT. Targeted HER2 treatment in advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2010;78:26–33. doi: 10.1159/000288295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wieduwilt MJ, Moasser MM. The epidermal growth factor receptor family: biology driving targeted therapeutics. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1566–1584. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7440-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Citri A, Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of secondary primary neoplasms

Characteristics of the 305 women with breast cancer who developed secondary malignant neoplasms and of 1,525 matched controls