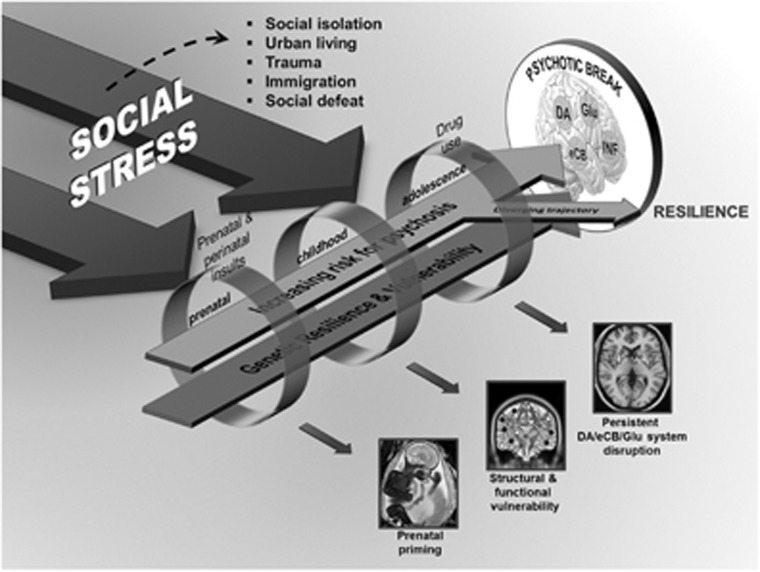

Figure 1.

We have focused our review on three main neurochemical systems involved in psychosis: the dopaminergic (DA), endocannabinoid (eCB), and neuroinflammatory systems. However, the prominent role of the glutamatergic (Glu) system in psychosis cannot be ignored. Stage-specific stressors are indicated above the rings, whereas the big arrows represent the critical effect of social stress across all stages. The rings indicate possible environmental factors at each developmental stage that increase the risk for psychosis. At the early developmental stage, genetic vulnerability may combine with prenatal and perinatal insults (eg, maternal immune activation) to prime some individuals. In addition, social stressors experienced in childhood may lead to structural and functional development abnormalities leading to enhanced vulnerability, perhaps through environmental impact on gene expression (epigenetics). At the adolescence stage, in addition to the important social stressors typical for this age range (moving out of parental home, new schooling, peers), drug use affecting DA, Glu, and eCB signaling may amplify the premorbid neurochemical aberrancies carried over from prior stages. At all developmental stages, the genetic traits of the individual confer either resilience against or vulnerability leading to disease. A psychotic break occurs when multiple factors coalesce together, typically in early adulthood. Psychosocial or pharmacological interventions, addressing social stress and/or targeting these neurochemical systems in specific timings (such as in adolescence) may divert this trajectory away from psychosis towards resilience and health.