Abstract

Objectives

This post hoc analysis of TIOtropium Safety and Performance In Respimat (TIOSPIR) evaluated safety and exacerbation efficacy in patients with stable (≥2 months) use of tiotropium HandiHaler 18 µg (HH18) prior to study entry, to evaluate whether there was a difference in risk for patients who switched from HH18 to tiotropium Respimat 2.5 µg (R2.5) or 5 µg (R5).

Setting

TIOSPIR (n=17 135) was an international, Phase IIIb/IV, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, event-driven trial.

Participants

Patients from TIOSPIR with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and postbronchodilator ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s to forced vital capacity ≤0.70, receiving HH18 before study entry, were analysed (n=2784).

Interventions

Patients were randomised to once-daily tiotropium R2.5 (n=914), R5 (n=918) or HH18 (n=952) for 2–3 years.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcomes: time to death (safety) and time to first COPD exacerbation (efficacy). Secondary outcomes: number of exacerbations and time to first major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE).

Results

Baseline characteristics were similar in all groups. Respimat had a similar mortality risk versus HH18 (vital status follow-up, HR; 95% CI R2.5: 0.87; 0.64 to 1.17; R5: 0.79; 0.58 to 1.07) with no significant differences in the risk and rates of exacerbations and severe exacerbations across treatment groups. Risk of MACE and fatal MACE was similar for Respimat versus HH18 (HR; 95% CI MACE R2.5: 0.73; 0.47 to 1.15; R5: 0.69; 0.44 to 1.08; fatal MACE R2.5: 0.57; 0.27 to 1.19; R5: 0.67; 0.33 to 1.34). Overall risk of a fatal event (on treatment) was lower for R5 versus HH18 (HR; 95% CI R2.5: 0.78; 0.55 to 1.09; R5: 0.62; 0.43 to 0.89).

Conclusions

This analysis indicates that it is safe to switch patients from tiotropium HandiHaler to tiotropium Respimat, and that the efficacy is maintained over the switch.

Trial registration number

NCT01126437; Post-results.

Keywords: Tiotropium, COPD, Respimat®, HandiHaler®, Switching, Efficacy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This post hoc analysis examined whether there was a difference in mortality or efficacy between those patients who were previously stable users (≥2 months) of tiotropium HandiHaler and continued with this delivery system during TIOSPIR and those who were subsequently randomised to tiotropium Respimat. This study will therefore be informative for physicians who are contemplating switching their patients from one inhaler to another.

Being one of the largest, long-term, randomised trials of a broad range of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) conducted to date, TIOSPIR lends itself to statistically powerful subgroup analyses. The inclusion of a wide range of spirometrically defined disease severities and the liberal inclusion criteria permitted a patient population that was highly representative of a typical COPD population (including patients with cardiac disorders).

The results of this study are more robust than findings from meta-analyses or database studies, which typically evaluate less frequent outcomes or rare events that may not be as rigorously collected as primary or secondary events, and in which confounding factors (such as disease severity) may not be fully adjusted for. A key limitation of the study is that it was a post hoc rather than predefined subgroup analysis. In addition, the design of the analysis does not allow for an evaluation of treatment initiation with the two inhalers in anticholinergic-naïve patients (results for this patient group are the subject of a separate analysis).

A further limitation of the study is that information on duration of treatment with tiotropium HandiHaler prior to randomisation and switch to Respimat was not collected. These data would provide additional valuable information on the characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study (eg, the proportion of patients who may have been considered more ‘stable’ on treatment with tiotropium due to a longer duration of therapy than other patients).

The current analysis also excluded patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment; however, placebo-controlled studies of patients with moderate renal impairment do not indicate an increased risk in these patients with the use of tiotropium Respimat.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of death and disability worldwide.1 Tiotropium bromide is a once-daily, long-acting anticholinergic (long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA)) and an established treatment option for COPD (SPIRIVA, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany). It is available in two formulations: a dry powder delivered via the HandiHaler device (18 µg once daily) and an aqueous solution delivered via the Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler (5 µg once daily).2 3 Tiotropium HandiHaler and Respimat have demonstrated similar improvements in lung function, symptoms and quality of life; they have similar pharmacokinetic profiles in patients with COPD.4–8

There is a large body of evidence supporting the clinical efficacy and safety of tiotropium administered via HandiHaler in patients with COPD.6 Safety concerns, however, were prompted after results of a post hoc pooled analysis of several trials (and subsequent meta-analyses) indicated a signal of increased risk of mortality with tiotropium Respimat, notably in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias.9–14 A pooled analysis of tiotropium HandiHaler studies, as well as the 4-year Understanding Potential Long-term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium (UPLIFT) (NCT00144339) study,8 15 16 did not indicate such a risk, with rate ratios favouring tiotropium HandiHaler versus placebo. Nevertheless, a possible interpretation of data from additional studies14 17 could have suggested a specific risk associated with tiotropium Respimat.

The TIOtropium Safety and Performance In Respimat (TIOSPIR) (NCT01126437) trial18 19 was conducted to provide a prospective evaluation of the safety and exacerbation efficacy of tiotropium Respimat versus tiotropium HandiHaler. TIOSPIR is the largest long-term, randomised, double-blind study in patients with COPD performed to date. It demonstrated that the risk of death was similar for tiotropium Respimat, at a dose of 2.5 or 5 µg, to that of HandiHaler 18 µg, with a HR of 0.96 for tiotropium Respimat 5 µg versus HandiHaler 18 µg. The risk of exacerbation and major adverse cardiovascular (CV) events (MACEs) did not differ significantly among the three groups.19

Despite providing reassurance on the safety of Respimat versus HandiHaler, the results from TIOSPIR have continued to raise some important questions regarding the two formulations. In particular, a population cohort study of patients aged ≥45 years receiving tiotropium identified several factors that influenced the likelihood of switching from HandiHaler to Respimat.20 These included COPD severity and comorbidities (notably neurological conditions).20 The authors of the study concluded that tiotropium users in clinical practice typically have more severe disease than patients included in randomised clinical trials and, therefore, called for further studies comparing the safety profile of the two tiotropium formulations.20

This post hoc analysis of TIOSPIR was conducted to address these concerns and to assess whether there was a difference in safety or efficacy between patients who had already received stable treatment with tiotropium HandiHaler and continued with this delivery system, and those who were subsequently randomised to tiotropium Respimat.

Methods

Study design

TIOSPIR was a long-term (2–3 years), international, multicentre, Phase IIIb, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group, actively controlled, event-driven trial in a large population (n=17 135) of patients with COPD. The study design has been described previously.18

Patients were randomised to one of three treatments: once daily tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg (two puffs of 1.25 µg) or 5 µg (two puffs of 2.5 µg) or once daily tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg. The study did not include a washout period from COPD treatments prior to randomisation. Patients attended clinic visits every 12 weeks, with a final visit 30 days after the end of treatment; all were followed up for vital status until the end of the study, even if their treatment was discontinued.

The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol and procedures were approved by the relevant institutional review boards and ethics committees. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study population

Tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg was the only LAMA marketed (tiotropium Respimat was not available) at the time of study enrolment (May 2010–April 2011) in the following countries: Australia, Canada, China, Georgia, Guatemala, India, Israel, New Zealand, Switzerland, Thailand, Tunisia and the USA. This subgroup analysis included patients with stable LAMA use prior to study enrolment (in the previous 2 months prior to visit 1) who were recruited from 339 centres across these countries, resulting in a population restricted to patients using tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg.

Patients were aged ≥40 years with a clinical diagnosis of COPD, postbronchodilator ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) to forced vital capacity ≤0.70, FEV1≤70% predicted, and had ≥10 pack-years of smoking history.

Exclusion criteria were chosen to select a typical COPD population. Patients with concomitant cardiac disease were permitted to participate in the study, unless they had experienced a myocardial infarction (MI) within the previous 6 months, were hospitalised for New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, or had a history of unstable or life-threatening arrhythmia requiring new treatment within the previous 12 months. In addition, patients with unstable COPD (exacerbation within 4 weeks), moderate or severe renal impairment as judged by the investigator, or other significant lung diseases, were excluded.

Patients were permitted to use their usual background treatment for COPD, except for other inhaled anticholinergics.

Assessments

The primary safety outcome was time to death from any cause (non-inferiority for Respimat 2.5 and 5 µg vs HandiHaler 18 μg) and the primary efficacy outcome was time to first COPD exacerbation (superiority for Respimat 5 µg vs HandiHaler 18 μg). COPD exacerbations were defined as the worsening of two or more major respiratory symptoms (dyspnoea, cough, sputum, chest tightness or wheezing) with a duration of at least 3 days and requiring specified treatment changes. Mild exacerbations required a newly prescribed maintenance bronchodilator; moderate exacerbations required a prescription for antibiotics, systemic corticosteroids or both; and severe exacerbation required hospitalisation.

Secondary outcomes included the number of COPD exacerbations, time to first moderate or severe exacerbation, time to first severe (hospitalised) exacerbation and time to non-fatal and fatal MACE (MACE included stroke, transient ischaemic attack, MI, sudden death, cardiac death, sudden cardiac death or fatal event in the system organ classes (SOCs) for cardiac and vascular disorders). SOCs were defined according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

Adverse event (AE) collection included all serious AEs, related AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation.

All AEs and deaths were reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring committee. In addition, all deaths were reviewed by an independent mortality adjudication committee (blinded to study-group assignments). For the non-fatal MACEs (stroke and MI) reported by site investigators, the accuracy of diagnosis/classification was verified by central reviewers, who were blinded to the study-group assignments.

Statistical analysis

HRs and 95% CIs for time-to-event end points were calculated using a Cox-proportional hazards regression model (with no covariate adjustment). Negative binomial regression models were used to compare annual exacerbation rates. Non-inferiority testing for the risk of death was performed using HandiHaler 18 μg as the reference treatment. Rate ratios and 95% CI were used to compare incidence rates.

For analysis of death (including fatal MACE), events occurring during treatment and vital status follow-up (follow-up for deaths even if the patient discontinued early) were considered (vital status analysis), while for all other analyses (including MACE and COPD exacerbations), only events with onset in the on treatment period were noted.

For the two primary outcomes, analyses on predefined subgroups specified by demographic variables, comorbid conditions, disease severity and concomitant medications, were performed.

Results

Study population

A total of 2784 patients from TIOSPIR who received stable tiotropium HandiHaler 18 µg prior to study entry were randomised and treated with blinded medication, and included in the analyses of mortality (tiotropium Respimat 2.5 µg: n=914; 5 µg: n=918; HandiHaler 18 µg: n=952). A total of 2782 patients were analysed for all other end points (two patients were excluded because they were from centres with data irregularities); baseline characteristics for this population are shown in table 1. Mean observation time (including vital status follow-up) was 858 days. In total, 679 patients (tiotropium Respimat 2.5 µg: n=229; 5 µg: n=211; HandiHaler 18 µg: n=239) prematurely discontinued from trial medication, including because of deaths.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg (n=914) |

Tiotropium Respimat 5 μg (n=917) |

Tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg (n=951) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 551 (60.3) | 568 (61.9) | 585 (61.5) |

| Female | 363 (39.7) | 349 (38.1) | 366 (38.5) |

| Age, mean years (SD) | 67.3 (8.6) | 67.4 (8.8) | 66.9 (8.9) |

| BMI, mean kg/m2 (SD) | 27.2 (6.3) | 26.9 (6.2) | 26.8 (6.2) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 262 (28.7) | 278 (30.3) | 290 (30.5) |

| Smoking history, mean pack-years (SD) | 51.9 (28.6) | 51.4 (29.0) | 52.7 (28.7) |

| Postbronchodilator spirometry, mean (SD) | |||

| FEV1, L | 1.21 (0.46) | 1.25 (0.47) | 1.24 (0.46) |

| FEV1, % predicted | 45.8 (14.2) | 46.7 (13.9) | 46.1 (13.7) |

| FVC, L | 2.62 (0.86) | 2.65 (0.87) | 2.64 (0.89) |

| Ratio of FEV1 to FVC | 0.47 (0.12) | 0.48 (0.11) | 0.48 (0.11) |

| GOLD stage, n (%) | |||

| I+II | 367 (40.2) | 398 (43.4) | 375 (39.4) |

| III | 411 (45.0) | 398 (43.4) | 443 (46.6) |

| IV | 128 (14.0) | 117 (12.8) | 124 (13.0) |

| Previous cardiac arrhythmia, n (%) | 154 (16.8) | 138 (15.1) | 158 (16.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 56 (6.1) | 50 (5.5) | 57 (6.0) |

| Bundle branch block | 51 (5.6) | 39 (4.3) | 35 (3.7) |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.4) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 7 (0.8) | 7 (0.8) | 16 (1.7) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 6 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 10 (1.1) |

| Bradycardia | 14 (1.5) | 18 (2.0) | 25 (2.6) |

| Atrioventricular block | 12 (1.3) | 10 (1.1) | 16 (1.7) |

| Other conduction disorders | 25 (2.7) | 27 (2.9) | 28 (2.9) |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 79 (8.6) | 91 (9.9) | 99 (10.4) |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 21 (2.3) | 24 (2.6) | 27 (2.8) |

| Previous IHD or CAD, n (%) | 154 (16.8) | 149 (16.3) | 184 (19.3) |

| Taking CV medication, n (%) | 554 (60.6) | 551 (60.1) | 568 (59.7) |

| β-blockers | 169 (18.5) | 178 (19.4) | 190 (20.0) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 164 (17.9) | 175 (19.1) | 174 (18.3) |

| Cardiac glycosides | 22 (2.4) | 19 (2.1) | 28 (2.9) |

| ACE inhibitors | 221 (24.2) | 210 (22.9) | 209 (22.0) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 111 (12.1) | 128 (14.0) | 127 (13.4) |

| Nitrates | 40 (4.4) | 46 (5.0) | 49 (5.2) |

| Antiarrhythmics class I or III (sodium or potassium channel blockers) | 6 (0.7) | 8 (0.9) | 15 (1.6) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 276 (30.2) | 300 (32.7) | 281 (29.5) |

| Anticoagulants* | 52 (5.7) | 45 (4.9) | 41 (4.3) |

| Antiplatelets | 55 (6.0) | 55 (6.0) | 63 (6.6) |

| Use of respiratory medication | |||

| LAMA | 914 (100.0) | 917 (100.0) | 951 (100.0) |

| LABA | 637 (69.7) | 631 (68.8) | 644 (67.7) |

| SABA | 615 (67.3) | 601 (65.5) | 628 (66.0) |

| ICS | 613 (67.1) | 612 (66.7) | 626 (65.8) |

| β-adrenergics | 615 (67.3) | 601 (65.5) | 628 (66.0) |

| LRTA | 50 (5.5) | 49 (5.3) | 56 (5.9) |

| Mucolytics | 35 (3.8) | 39 (4.3) | 44 (4.6) |

| Supplemental oxygen | 123 (13.5) | 120 (13.1) | 122 (12.8) |

| Xanthines | 92 (10.1) | 73 (8.0) | 88 (9.3) |

Two patients from centres with data irregularities were excluded.

*Includes vitamin K antagonists, direct thrombin inhibitors, factor Xa inhibitors.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CV, cardiovascular; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; LRTA, leucotriene receptor antagonist; MI, myocardial infarction; SABA, short-acting β2-agonist.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar in the three tiotropium groups (table 1). The mean age of patients was 67.2 years, the majority (61.3%) were male, 29.8% were current smokers and mean postbronchodilator FEV1 was 46.2% of predicted. The majority of patients were Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Stages II (40.8%) and III (45.0%). Overall, 68.7% of patients were taking a long-acting β2-agonist at baseline and a similar proportion of patients (66.5%) were taking inhaled corticosteroids. The majority (60.1%) of patients were also receiving CV medications at baseline and 16.2% of patients had a history of cardiac arrhythmia (the most common type being atrial fibrillation or flutter; table 1).

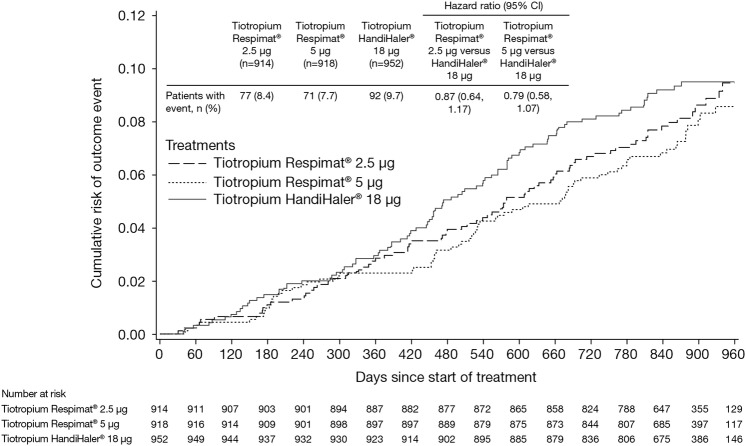

Mortality end points

Both Respimat doses were non-inferior to HandiHaler with respect to the primary end point of time to death (vital status analysis)—Respimat 2.5 µg: HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.64 to 1.17; 5 µg: HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.07 (figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis, the risk of a fatal AE was lower in the Respimat 5 µg versus the HandiHaler group (HR 0.62; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.89; Respimat 2.5 µg: HR 0.78; 95% CI 0.55 to 1.09) (see E-figure 1). Causes of death were similar across the treatment groups, including death from cardiac disorders and MACE. Although the incidence of cardiac disorders was higher in the HandiHaler group (n=5 vs 2), the very small number of cardiac deaths, the small absolute risk difference and the wide CIs around the HRs, do not indicate any significant difference (table 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to death by treatment (vital status analysis).

Table 2.

Adjudicated primary causes of death (vital status analysis)

| Variable | Tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg (n=914) |

Tiotropium Respimat 5 μg (n=918) |

Tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg (n=952) |

Rate ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg vs HandiHaler 18 μg |

Tiotropium Respimat 5 μg vs HandiHaler 18 μg |

||||

| Adjudicated causes of death, n (rate/100 patient-years) | 77 (3.6) | 71 (3.3) | 92 (4.1) | 0.87 (0.64 to 1.17) | 0.79 (0.58 to 1.07) |

| Cardiac disorders | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 0.41 (0.08 to 2.14) | 0.41 (0.08 to 2.10) |

| General disorders | 12 (0.6) | 14 (0.6) | 18 (0.8) | 0.69 (0.33 to 1.43) | 0.79 (0.39 to 1.59) |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified | 25 (1.2) | 16 (0.7) | 18 (0.8) | 1.44 (0.79 to 2.64) | 0.91 (0.46 to 1.78) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 29 (1.4) | 26 (1.2) | 33 (1.5) | 0.91 (0.55 to 1.50) | 0.80 (0.48 to 1.34) |

| COPD | 28 (1.3) | 25 (1.1) | 28 (1.3) | 1.04 (0.61 to 1.75) | 0.91 (0.53 to 1.56) |

| Infections and infestations | 6 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 1.55 (0.44 to 5.51) | 1.53 (0.43 to 5.42) |

| Nervous system disorders | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 0.52 (0.09 to 2.83) | 0.25 (0.03 to 2.28) |

| Patients with fatal MACE, n (rate/100 patient-years) | 11 (0.5) | 13 (0.6) | 20 (0.9) | 0.57 (0.27 to 1.19) | 0.66 (0.33 to 1.33) |

| Sudden death | 5 (0.2) | 8 (0.4) | 5 (0.2) | 1.04 (0.30 to 3.58) | 1.63 (0.53 to 4.98) |

| Sudden cardiac death | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) | 0.41 (0.08 to 2.14) | – |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 4 (0.2) | 0.26 (0.03 to 2.32) | 0.25 (0.03 to 2.28) |

| Cardiac failure congestion | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 1.04 (0.06 to 16.56) | 1.02 (0.06 to 16.29) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Aortic dissection | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | – | – |

| Aortic valve stenosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | – | – |

| Arteriosclerosis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Cardiac failure chronic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | – | – |

| Cardiac valve disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Cor pulmonale | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | – | – |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | – | – |

| Peripheral vascular disorder | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

Time at risk adjusted rate ratios of adjudicated causes of death by treatment, MedDRA (V.16.0) system organ class and preferred term.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event (stroke, transient ischaemic attack, myocardial infarction, sudden death, cardiac death, sudden cardiac death or fatal event in the system organ classes for cardiac and vascular disorders); MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

No significant treatment interactions were observed for either Respimat dose compared with HandiHaler in the subgroups of patients with baseline cardiac arrhythmia (Respimat 2.5 µg: HR 1.03; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.84; 5 µg: HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.44 to 1.56) or cardiac history defined as history of MI, ischaemic heart disease/coronary artery disease, cardiac arrhythmia or heart failure (Respimat 2.5 µg: HR 1.01; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.57; 5 µg: HR 0.93; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.46) (see E-figure 2a, b).

Exacerbation efficacy

There was no difference in the primary end point of time to first COPD exacerbation (on treatment) in either of the Respimat groups versus HandiHaler (HR 1.03; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.16; and HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.08 for Respimat 2.5 and 5 µg vs HandiHaler, respectively) (table 3 and E-figure 3a). The median time to first exacerbation was 390 and 466 days in the Respimat 2.5 and 5 µg groups, respectively, and 418 days in the HandiHaler group. The number of exacerbations was similar between the treatment groups (adjusted rate/patient-year: 0.83, 0.83 and 0.81 in the Respimat 2.5 or 5 µg and HandiHaler groups, respectively).

Table 3.

Risk and rate of exacerbations (on treatment analysis*)

| Variable | Tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg (n=914) |

Tiotropium Respimat 5 μg (n=917) |

Tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg (n=951) |

HR (95% CI); p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg vs HandiHaler 18 μg |

Tiotropium Respimat 5 μg vs HandiHaler 18 μg |

||||

| Any exacerbation | |||||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 573 (62.7) | 560 (61.1) | 578 (60.8) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.16); p=0.614 | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08); p=0.517 |

| Number of events | 1484 | 1508 | 1548 | ||

| Adjusted rate of events/patient-year (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.91) | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.90) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.87) | ||

| Moderate-to-severe exacerbation | |||||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 561 (61.4) | 550 (60.0) | 571 (60.0) | 1.01 (0.90 to 1.14); p=0.817 | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.07); p=0.441 |

| Number of events | 1462 | 1474 | 1525 | ||

| Adjusted rate of events/patient-year (95% CI) | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.89) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.88) | 0.79 (0.73 to 0.86) | ||

| Severe (hospitalised) exacerbation | |||||

| Patients with event, n (%) | 172 (18.8) | 173 (18.9) | 172 (18.1) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.29); p=0.690 | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.28); p=0.760 |

| Number of events | 264 | 283 | 267 | ||

| Adjusted rate of events/patient-year (95% CI) | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.18) | 0.16 (0.13 to 0.19) | 0.14 (0.12 to 0.17) | ||

Two patients from centres with data irregularities were excluded.

*Includes first day after treatment stop.

No difference was observed between the Respimat-treated population and HandiHaler groups with respect to the secondary end points of time to first moderate-to-severe exacerbation and time to first severe (hospitalised) exacerbation (table 3; E-figure 3b, c). The frequency of moderate-to-severe and hospitalised exacerbations was low and similar between treatment groups (table 3). No significant treatment interactions were observed for either of the Respimat doses versus HandiHaler for the predefined subgroups with respect to exacerbation risk.

Other safety end points

Serious AEs were reported in 42.5% of patients, with similar frequencies between each treatment group (table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of AEs and MACE by treatment (on treatment analysis*)

| Variable | Tiotropium Respimat 2.5 μg (n=914) |

Tiotropium Respimat 5 μg (n=917) |

Tiotropium HandiHaler 18 μg (n=951) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE, n (%) | 711 (77.8) | 721 (78.6) | 737 (77.5) |

| Drug-related AEs, n (%) | 73 (8.0) | 66 (7.2) | 75 (7.9) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 42 (4.6) | 37 (4.0) | 31 (3.3) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 16 (1.8) | 15 (1.6) | 18 (1.9) |

| Nervous system disorders | 11 (1.2) | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.6) |

| Cardiac disorders | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 8 (0.8) |

| Serious AEs, n (%)† | 373 (40.8) | 399 (43.5) | 409 (43.0) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 198 (21.7) | 203 (22.1) | 212 (22.3) |

| Infections and infestations | 118 (12.9) | 115 (12.5) | 110 (11.6) |

| Neoplasms—benign, malignant and unspecified (including cysts and polyps) | 71 (7.8) | 73 (8.0) | 65 (6.8) |

| Cardiac disorders | 50 (5.5) | 56 (6.1) | 71 (7.5) |

| Nervous system disorders | 26 (2.8) | 31 (3.4) | 34 (3.6) |

| General disorders and administration-site conditions | 18 (2.0) | 24 (2.6) | 30 (3.2) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 11 (1.2) | 12 (1.3) | 15 (1.6) |

| Patients with MACE, n (%)‡ | 34 (3.7) | 31 (3.4) | 57 (6.0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 8 (0.9) | 6 (0.7) | 11 (1.2) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 6 (0.7) | 6 (0.7) | 10 (1.1) |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 4 (0.4) | 11 (1.2) | 6 (0.6) |

| Patients with MACE, n (%)§ | 32 (3.5) | 31 (3.4) | 46 (4.8) |

Two patients from centres with data irregularities were excluded.

*Includes thirty days after treatment stop.

†Frequency of patients with serious AEs, as determined by the investigator, occurring in 15 or more patients at the MedDRA (V.16.0) preferred term level by treatment and primary system organ class.

‡Frequency of patients with AEs classified as MACE, as determined by the investigator, occurring in 10 or more patients at the preferred term level by treatment and primary system organ class.

§Frequency of patients with AEs classified as MACE based on adjudicated causes of death.

AE, adverse event; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event (stroke, transient ischaemic attack, myocardial infarction, sudden death, cardiac death, sudden cardiac death or fatal event in the system organ classes for cardiac and vascular disorders); MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities.

For the secondary safety end points of time to first MACE, there was no significant difference between the Respimat and HandiHaler groups (table 4 and E-figure 4a, b). The incidence of first MACE was 3.5% in the Respimat 2.5 µg group, 3.4% in the 5 µg group and 4.8% in the HandiHaler group (on treatment analysis, based on adjudicated causes of death) (table 4) (HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.15, p=0.179; and HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.44 to 1.08, p=0.107 for Respimat 2.5 and 5 µg vs HandiHaler, respectively).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of TIOSPIR demonstrated that patients receiving stable (≥2 months) treatment with tiotropium HandiHaler 18 µg at baseline who changed to treatment with tiotropium Respimat 2.5 or 5 µg were at a similar (though numerically lower) risk of death and MACE as patients who continued to receive HandiHaler 18 µg. It also found that recipients of tiotropium Respimat had a similar risk of exacerbation as those receiving tiotropium HandiHaler. These findings are consistent with the TIOSPIR study results.

Evidence from previous studies, primarily retrospective analyses, has raised concerns that tiotropium delivered by Respimat may be associated with adverse CV effects in patients with CV comorbidities.9–14 17 Approximately 16% of patients in this post hoc analysis had a history of cardiac arrhythmias. The subgroup analyses in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmia and those with cardiac history, predefined in the main study, demonstrated no significant difference between Respimat and HandiHaler recipients with respect to mortality and exacerbation risk; in line with the main study, no increased risk could be identified, even in the subgroup of patients who changed from HandiHaler to Respimat.

There was a 38% reduced risk of fatal AEs in the Respimat 5 µg group versus the HandiHaler group. Together with a numerical (though not statistically significant) imbalance in favour of both Respimat doses with respect to incidence of first MACE, this argues against any deleterious effect of tiotropium when given using Respimat. Importantly, previous studies of long-term treatment of patients with COPD with tiotropium Handihaler in the 4-year UPLIFT study did not indicate any adverse effect on MACE or fatal MACE versus placebo.8

Other recent studies have provided additional support for the safety of Respimat in patients with COPD. A pharmacokinetic study4 showed that, although the overall profile was similar, systemic exposure to tiotropium following the use of tiotropium Respimat was slightly lower compared with tiotropium HandiHaler. A post hoc analysis of mortality and exacerbation data from six clinical trials of tiotropium Respimat and tiotropium HandiHaler (including UPLIFT and TIOSPIR) showed similar effects on both, mortality and exacerbations, between Respimat 5 µg and HandiHaler 18 µg.21 In addition, risk of exacerbation was lower for both tiotropium formulations versus placebo, with numerically higher efficacy for Respimat 5 μg.21 In another study, combined analysis of all trials from the tiotropium clinical trial database involving Holter-ECG monitoring in patients with COPD did not demonstrate any clinically relevant differences between Respimat and HandiHaler with respect to changes in heart rate or in the proportion of patients experiencing supraventricular or ventricular premature beats while on tiotropium.22 Finally, a pooled analysis of AE data from 28 randomised trials of HandiHaler and seven Respimat studies did not indicate a significantly increased risk of fatal AEs or fatal/non-fatal MACE with either inhaler versus placebo.23

A recent drug utilisation study investigated the influence of factors on the probability of receiving tiotropium HandiHaler or Respimat and determined the existence of a channelling effect both in incident users and in patients switching from the HandiHaler to the Respimat formulation.20 It found that comorbidities and disease severity influence the likelihood of switching from HandiHaler to Respimat, and called for further studies comparing the safety profile of the two formulations.20 The present study addresses any safety and efficacy concerns regarding the switch between formulations.

TIOSPIR is the largest COPD study conducted to date, comprising over 34 000 patient-years of exposure to tiotropium.19 Clinical trials are often criticised for not recruiting patients typical of the population treated in routine clinical practice. The liberal inclusion criteria of the TIOSPIR study permitted a large number of patients to be included, with a wide range of disease severities and history of cardiac disorders; it was thus representative of a typical COPD population (although it excluded patients with severe, unstable CV disease or moderate-to-severe renal impairment). In addition, the large size of the population allowed for statistically powerful subgroup analyses.

The results of TIOSPIR can be regarded as more robust than findings from meta-analyses or database studies, which typically evaluate less frequent outcomes from clinical studies that may not have been collected as rigorously as primary or secondary outcome measures.24 Database studies evaluating rare events may not fully adjust confounding by severity; for example, it is difficult to interpret the independent effect of tiotropium Respimat without a detailed assessment of underlying COPD and CV risk.24 Furthermore, differences often exist in the populations studied, doses of treatment and length of follow-up.

A limitation of the study is the post hoc design involving a subgroup of patients with a lower number of patients than in the main study. The design of this post hoc analysis does not allow for an evaluation of treatment initiation with the two inhalers in anticholinergic-naïve patients; results for these patients will be reported elsewhere.

This post hoc analysis was restricted to patients who were receiving tiotropium HandiHaler 18 µg treatment for at least 2 months prior to randomisation. It is unfortunate that data on the duration of treatment outside of the 2-month cut-off period were not collected, as this would facilitate better characterisation of the patients who were included in the study. For example, patients who had been treated with tiotropium HandiHaler for longer than 2 months could be considered more ‘stable’ on this treatment than patients who were recently initiated on tiotropium.

While the current analysis excluded patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment, placebo-controlled studies of patients with moderate renal impairment do not indicate an increased risk in these patients with the use of tiotropium Respimat.25 26 A pooled safety analysis of 22 Phase III and IV clinical trials of tiotropium HandiHaler and Respimat (N=10 805 patients) demonstrated no trend for increased incidence rate ratios of AEs with worsening renal function for either formulation.25 26 In this current post hoc analysis, the group of patients with severe renal impairment was too small to be analysed.

Conclusion

This post hoc analysis of the pivotal TIOSPIR trial provides additional evidence for the safety of tiotropium delivered by Respimat, which demonstrated a similar safety profile to tiotropium HandiHaler in patients with COPD, including those with a history of cardiac disorders. Based on this analysis, it can be concluded that it is safe to switch patients from tiotropium HandiHaler to tiotropium Respimat, and that the efficacy is maintained over the switch.

Acknowledgments

Editorial and writing support was provided by Carol A Richter and Sarah J Petit from PAREXEL, and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Footnotes

Contributors: RD, PMAC, AA, NM, AF, RW and DD contributed to the study design, interpretation of analyses and drafting of the manuscript. AM performed the statistical analyses, and contributed to the interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. All the authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript. RD and DD are the guarantors.

Funding: The TIOSPIR trial was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. The funding source participated in the design and conduct of the study, the analysis or interpretation of the data and the preparation of the manuscript before publication.

Competing interests: RD, DD, RW, PMAC, AA, NM, AF and AM have support from Boehringer Ingelheim for the submitted work. NM, AF and AM are full-time employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. Outside the submitted work, RD reports receiving personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis; RW reports grants, personal fees and other from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Bristol-Myers-Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Pulmonx, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi/Mannkind, Spiration, Teva, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Forest Labs and Sunovion; PMAC reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Takeda; DD reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Dey Pharma LP, Pfizer, Novartis and Nycomed; AA reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer-Schering Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dey Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol and procedures were approved by the relevant institutional review boards and ethics committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2014. http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report2014_Feb07.pdf

- 2.Boehringer Ingelheim. Summary of Product Characteristics: Spiriva 18 microgram inhalation powder, hard capsule 2013. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/10039/SPC/Spiriva+18microgram+inhalation+powder,+hard+capsule

- 3.Boehringer Ingelheim. Summary of Product Characteristics: Spiriva Respimat 2.5 micrograms solution for inhalation 2014. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/20134

- 4.Hohlfeld JM, Sharma A, van Noord JA et al. . Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tiotropium solution and tiotropium powder in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Pharmacol 2014;54:405–14. 10.1002/jcph.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karner C, Chong J, Poole P. Tiotropium versus placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;7:CD009285 10.1002/14651858.CD009285.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating GM. Tiotropium bromide inhalation powder: a review of its use in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Drugs 2012;72:273–300. 10.2165/11208620-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating GM. Tiotropium Respimat® Soft Mist™ inhaler: a review of its use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Drugs 2014;74:1801–16. 10.1007/s40265-014-0307-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S et al. . A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehringer Ingelheim. Tiotropium (Spiriva) Respimat: evaluation of fatal events 2010. http://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/content/dam/internet/opu/clinicaltrial/com_EN/results/Pooled%20analysis/PA_205.372_251_252_254_255_U10-3255-01.pdf

- 10.Dong YH, Lin HH, Shau WY et al. . Comparative safety of inhaled medications in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Thorax 2013;68:48–56. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loke YK, Singh S. Risks associated with tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: overview of the evidence to date. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2012;3:123–31. 10.1177/2042098612438388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathioudakis AG, Chatzimavridou-Grigoriadou V, Evangelopoulou E et al. . Comparative mortality risk of tiotropium administered via HandiHaler or Respimat in COPD patients: are they equivalent? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2014;28:91–7. 10.1016/j.pupt.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh S, Loke YK, Enright PL et al. . Mortality associated with tiotropium mist inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;342:d3215 10.1136/bmj.d3215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verhamme KM, Afonso A, Romio S et al. . Use of tiotropium Respimat Soft Mist Inhaler versus HandiHaler and mortality in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2013;42:606–15. 10.1183/09031936.00005813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celli B, Decramer M, Kesten S et al. . Mortality in the 4-year trial of tiotropium (UPLIFT) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:948–55. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0876OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kesten S, Celli B, Decramer M et al. . Tiotropium HandiHaler in the treatment of COPD: a safety review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2009;4:397–409. 10.2147/COPD.S4802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beasley R. Tiotropium Respimat increases the risk of mortality: pro. Eur Respir J 2013;42:584–9. 10.1183/09031936.00042113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wise RA, Anzueto A, Calverley P et al. . The Tiotropium Safety and Performance in Respimat Trial (TIOSPIR), a large scale, randomized, controlled, parallel-group trial-design and rationale. Respir Res 2013;14:40 10.1186/1465-9921-14-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise RA, Anzueto A, Cotton D et al. . Tiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPD. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1491–501. 10.1056/NEJMoa1303342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotta F, Da Cas CR, Rajevic M et al. . Risk factors influencing the prescription of tiotropium Respimat formulation: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006619 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahl R, Schmidt H, Koenen-Bergmann M et al. . Mixed treatment analysis comparing Tiotropium HandiHaler® and Respimat®. Poster (P-925) presented at ERS 2014, Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hohlfeld JM, Furtwaengler A, Koenen-Bergmann M et al. . Cardiac safety of tiotropium in patients with COPD: a combined analysis of Holter-ECG Data From Four Randomized Clinical Trials. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halpin D, Dahl R, Hallmann C et al. . Tiotropium HandiHaler® And Respimat®. COPD: a safety analysis on pooled data [Abstract]. Presented at ATS International Conference; 2014, San Diego, California, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes NC, Jones PW, Davis KJ. Safety of tiotropium through the HandiHaler: why did meta-analyses and database studies appear to give a false alarm? Thorax 2014;69:598–9. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tashkin DP, Metzdorf N, Hallman C et al. . Safety of tiotropium in renally impaired patients. Eur Respir J 2014;44:(Suppl 58), Abstract 923. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miravitlles M, Price D, Rabe KF et al. . Comorbidities of patients in tiotropium clinical trials: comparison with observational studies of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:549–64. 10.2147/COPD.S71913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]