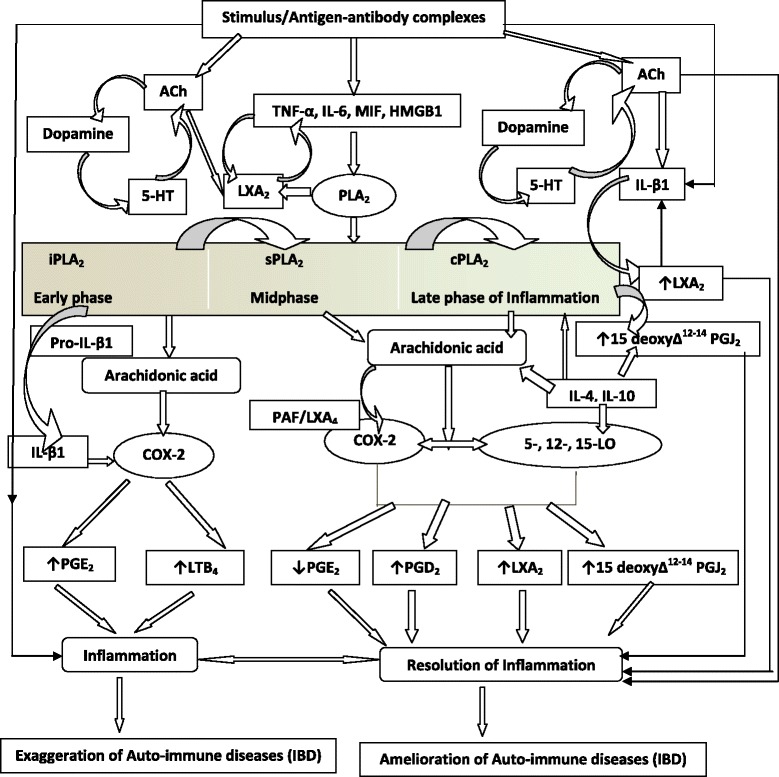

Fig. 1.

Scheme showing role of pro and anti-inflammatory bioactive lipids in IBD. For easy understanding only LXA4 has been depicted in the figure. It is to be noted that resolvins, protectins, maresins and nitrolipids may follow the same pathway as that of LXA4 from the respective precursors (EPA and DHA: eicosapentaneoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid respectively). Possible interaction among cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (Ach), serotonin, dopamine and LXA4 is also depicted in the figure. There are three classes of phospholipases that control the release of AA and other PUFAs: calcium-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), secretory PLA2 (sPLA2), and cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2). Each class of PLA2 is further divided into isoenzymes for which there are 10 for mammalian sPLA2, at least 3 for cPLA2, and 2 for iPLA2. During the early phase of inflammation, COX-derived PGs and lipoxygenase-derived LTs initiate exudate formation and inflammatory cell influx. TNF-α causes an immediate influx of neutrophils concomitant with PGE2 and LTB4 production, whereas during the phase of resolution of inflammation an increase in LXA4 (lipoxin A4), PGD2 and its product 15deoxyΔ12-14PGJ2 formation occurs that induces resolution of inflammation with a simultaneous decrease in PGE2 synthesis that stops neutrophil influx and enhances phagocytosis of debris. Thus, there appears to be two waves of release of AA and other PUFAs: one at the onset of inflammation that causes the synthesis and release of PGE2 and a second at resolution for the synthesis of anti-inflammatory PGD2, 15deoxyΔ12-14PGJ2, and lipoxins that are necessary for the suppression of inflammation. Thus, COX-2 enzyme has both harmful and useful actions by virtue of its ability to give rise to pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory PGs and LXs. Increased type VI iPLA2 protein expression was found to be the principal isoform expressed from the onset of inflammation up to 24 h, whereas type IIa and V sPLA2 was expressed from the beginning of 48 h till 72 h while type IV cPLA2 was not detectable during the early phase of acute inflammation but increased progressively during resolution peaking at 72 h. This increase in type IV cPLA2 was mirrored by a parallel increase in COX-2 expression. The increase in cPLA2 and COX-2 occurred in parallel, suggesting a close enzymatic coupling between these two. Thus, there is a clear-cut role for different types of PLA2 in distinct and different phases of inflammation. Selective inhibition of cPLA2 resulted in the reduction of pro-inflammatory molecules PGE2, LTB4, IL-1β, and platelet-activating factor (PAF). Furthermore, inhibition of types IIa and V sPLA2 not only decreased PAF and LXA4 (lipoxin A4) but also resulted in a reduction in cPLA2 and COX-2 activities. These results suggest that sPLA2-derived PAF and LXA4 induce COX-2 and type IV cPLA2. IL-1β induced cPLA2 expression. This suggests that one of the functions of IL-1 is not only to induce inflammation but also to induce cPLA2 expression to initiate resolution of inflammation. Synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone inhibited both cPLA2 and sPLA2 expression, whereas type IV iPLA2 expression is refractory to its suppressive actions. Activated iPLA2 contributes to the conversion of inactive proIL-1β to active IL-1β, which in turn induces cPLA2 expression that is necessary for resolution of inflammation. LXs, especially LXA4 inhibit TNF-α-induced production of ILs; promote TNF-α mRNA decay, TNF-α secretion, and leukocyte trafficking and thus attenuated inflammation. Though the proposal presented has focused mainly on LXA4, it may be mentioned here that there could be a significant role for other anti-inflammatory bioactive lipids such as resolvins, protectins, maresins and nitrolipids in IBD. Thus, in all the places wherever LXA4 is mentioned, it may be assumed that resolvins, protectins, maresins and nitrolipids also have an important role to play along with LXA4