Abstract

Background and study aims: Barrett’s esophagus is a common condition that is widely encountered in clinical practice. This European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) survey aimed to determine practice patterns amongst European clinicians with regard to the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus.

Methods: Clinicians attending the ESGE learning area at the United European Gastroenterology Week in 2014 were invited to complete a 10-question survey. This survey was programed on to two Apple iPads. Information was gathered with regard to demographics, practice settings, and diagnosis and management strategies for Barrett’s esophagus.

Results: In total, 163 responses were obtained. Over half of respondents (61 %) were based in university hospitals, the majority (78 %) were aged 30 – 50 and half had more than 10 years’ experience; 66 % had attended courses on Barrett’s esophagus and more than half (60 %) used the Prague C & M classification. Advanced imaging was used by 73 % of clinicians and 72 % of respondents stated that their group practiced ablation therapy. Most (76 %) practiced surveillance for non-dysplastic Barrett’s, 6 % offered ablation therapy in some situations, and 18 % offered no intervention. For low grade dysplasia, 56 % practiced surveillance, 19 % ablated some cases and 15 % ablated all cases. In total, 32 % of clinicians referred high grade dysplasia to expert centers, with 20 % referring directly for surgery and 46 % using ablation therapy in certain cases. Endoscopic mucosal resection was the most commonly used ablation technique (44 %).

Conclusions: There has been reasonable uptake of the Prague C & M classification for describing Barrett’s esophagus, and ablation is widely practiced. However, practice patterns for Barrett’s esophagus vary widely between clinicians with clear guidance and quality standards required.

Background

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition commonly found at upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and is well recognized as a risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma 1 2. Esophageal adenocarcinoma has shown a steady rise in incidence across Europe 3. Survival rates are poor with a 5-year survival rate in the UK of only 12.5 %.

The use of a standardized classification system for Barrett’s esophagus 4 along with guidelines on biopsy protocols 5 6 have led to improved monitoring and increased detection of dysplastic changes and early cancers. Further work has suggested that novel imaging techniques such as chromoendoscopy and virtual chromoendoscopy can improve the accuracy with which dysplastic changes in Barrett’s esophagus can be detected 7. Surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus remains a widely debated topic, but most societies agree that some form of regular endoscopic surveillance with protocol driven biopsies is required 1 2 8.

Esophagectomy was previously the recognized surgical treatment for high grade dysplasia or cancer in Barrett’s esophagus but therapeutic endoscopic techniques are becoming more widely available, and are now included in many guidelines. The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines 1 now recommend that endoscopic resection should be preferred to esophagectomy for high grade dysplastic changes and early adenocarcinoma confined to the mucosa. It is also suggested that endoscopic therapy to treat advanced changes such as high grade dysplasia or submucosal invasive adenocarcinoma should be carried out in specialist centers with experience of the techniques.

Several endoscopic techniques have been described to treat high grade dysplasia and early esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been shown to decrease disease progression by eliminating dysplastic change and intestinal metaplasia 7 and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is recommended for removing visible lesions. Recent studies have suggested that EMR to remove visible lesions followed by RFA results in high rates of clearance of Barrett’s changes 9 10.

Given the recent changes to management guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus and particularly the increasing availability of therapeutic endoscopic techniques, it is unclear how clinicians are managing Barrett’s esophagus. A recent survey carried out in the United States investigated the endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus, mainly in the community setting 11. This study aimed to investigate practice patterns amongst clinicians in Europe using a similar strategy.

Methods

A survey was carried out amongst attendees at the United European Gastroenterology Week in Vienna (November 2014). The survey was based on a similar survey done in the United States in 2013, and this was carried out as a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) initiative on behalf of the ESGE research committee. Permission was obtained from the original author of the American survey 11 to reproduce it in a European setting.

Survey questionnaire

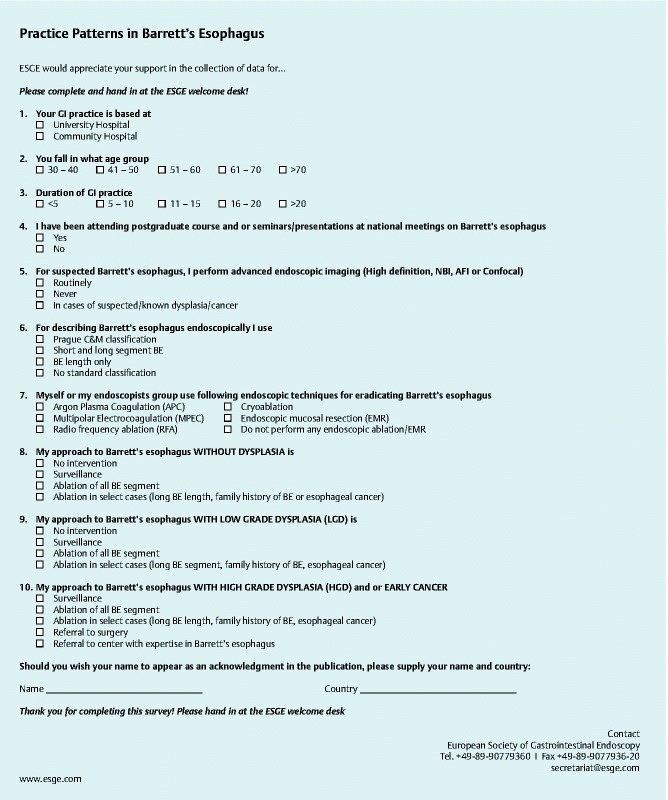

The questionnaire consisted of 10 separate questions (Fig. 1). The first four questions were demographic information about age (range 30 – 40, 41 – 50, 51 – 60, 61 – 70, > 70), practice setting (community hospital or university hospital), duration of gastrointestinal practice in years (< 5, 5 – 10, 11 – 15, 16 – 20, > 20) and whether they attended postgraduate courses, seminars or meetings about Barrett’s esophagus. The next two questions concerned the description of Barrett’s esophagus endoscopically (no standard description, total Barrett’s esophagus length, short and long Barrett’s length and Prague C & M classification) and how often advanced imaging techniques were used (never, routinely, in certain cases). Advanced imaging techniques included high definition (HD) endoscopy, narrow-band imaging (NBI), autofluorescence imaging (AFI) or confocal imaging. The remaining questions addressed which interventional techniques were used to ablate Barrett’s esophagus and how various stages of Barrett’s were managed (no dysplasia, low grade dysplasia, high grade dysplasia/early cancer). Participants were also asked if they wished their name to be listed as an acknowledgement in any publications arising from the survey.

Fig. 1.

ESGE survey questionnaire (available on request).

Distribution and participants

The survey was programed onto two Apple iPads using the QuickTapSurvey application (TabbleDabble Inc, Toronto, Canada). They were kept in the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) learning area at the 2014 United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW) in Vienna, Austria. Any delegate could access this area which offered practical endoscopy skill stations, interactive lectures, and video teaching. Delegates were approached on entry to the learning area and invited to complete the survey. Paper forms were also available, with the answers subsequently entered into the survey application. There was an incentive of free attendance at an ESGE endoscopy event for one delegate who was chosen at random at the end of the conference. The paper form of the questionnaire is displayed in Fig. 1.

Data collection and statistical analysis

The data collected from the survey were automatically entered by the software into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, United States) for initial analysis. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages and data were then uploaded to SPSS (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States) for further analysis. Comparisons were made between community and university clinicians using Fisher’s exact test and multivariate analysis was performed to investigate independent factors that may be associated with the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Given the wide representation of countries at UEGW, a comparison was also carried out between European gastroenterologists and those from the rest of the world.

Results

Demographic data

A total of 163 participants filled out the survey during the conference (Table 1). As the survey was filled out by delegates in the ESGE learning area, it was not possible to calculate a response rate. In total, 61 % (100/163) of responses were from university hospital-based clinicians with the remaining 39 % (63/163) based in community hospitals.

Table 1. Demographics, use of advanced imaging and classification of Barrett’s esophagus (n = 163).

| % (n) | |

| Age range, years | |

| 30 – 40 | 42 (69) |

| 41 – 50 | 36 (59) |

| 51 – 60 | 19 (31) |

| 61 – 70 | 2 (4) |

| > 70 | 0 (0) |

| Experience, years | |

| < 5 | 26 (42) |

| 5 – 10 | 25 (40) |

| 11 – 15 | 23 (38) |

| 16 – 20 | 19 (17) |

| > 20 | 15 (25) |

| Use of advanced imaging | |

| Never | 27 (44) |

| Certain cases | 32 (52) |

| Routinely | 41 (67) |

| Endoscopic classification of Barrett’s | |

| None | 9 (14) |

| Length only | 5 (8) |

| Short and long | 26 (43) |

| Prague C & M | 60 (98) |

The majority of respondents (78 %, 128/163) fell within the age range of 30 – 50 and 50 % of clinicians had more than 10 years of experience. Participants in the survey were asked to provide their name, country, and contact details should they wish to be in the draw for the free attendance at an ESGE event. In total, 66 % (107/163) of respondents provided this information, of whom 59 % (63/107) were from European countries and 41 % (44/107) were from outside of Europe. The most represented countries were Italy, Egypt, and Spain with 14, 10, and 7 responses, respectively. Other countries had a maximum of four replies.

Clinician practice patterns

In total, 66 % of respondents had attended courses or updates on the management of Barrett’s esophagus; 60 % of clinicians used the validated Prague C & M classification to describe Barrett’s esophagus at endoscopy (Table 1); 26 % documented short and long segments of Barrett’s esophagus with 5 % commenting on length only, and 9 % having no standard classification. There were no statistically significant differences between university-based and community-based gastroenterologists.

Techniques for eradication of Barrett’s esophagus

In total, 72 % of respondents stated that either they or their group of endoscopists undertook some form of therapy to ablate Barrett’s esophagus. The most commonly used techniques for the treatment of Barrett’s esophagus were endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), argon plasma coagulation (APC) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). EMR was used in 44 % of hospitals, APC in 41 %, and RFA in 31 %. Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC) and cryoablation were only used in 6 % and 5 % of centers, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Practice patterns for the management of Barrett’s esophagus (n = 163).

| No intervention | Surveillance | Ablation of all Barrett’s segments | Ablation in selected cases | Referral to expert center | Referral to surgery | |

| BE with no dysplasia, % (n) | 18 (29) | 76 (124) | 4 (6) | 2 (4) | – | – |

| BE with low grade dysplasia, % (n) | 9 (15) | 56 (92) | 19 (31) | 15 (25) | – | – |

| BE with high grade dysplasia, % (n) | – | 2 (3) | 37 (61) | 9 (14) | 32 (52) | 20 (33) |

Management of Barrett’s esophagus

The majority of clinicians used advanced imaging techniques, including HD endoscopy, NBI, AFI, and confocal imaging, in the assessment of Barrett’s esophagus (Table 1); 41 % used these regularly and 32 % used them in specific cases. Although slightly more university-based clinicians used advanced imaging techniques, there was no statistically significant difference between university and community-based gastroenterologists (P = 0.27). This may in part be due to much wider availability of HD endoscopy in recent years. When managing non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, the majority (76 %) of respondents practiced surveillance with 18 % offering no intervention, 4 % opted for ablation in select cases, and 2 % treated the whole segment (Table 3). Just over half of the respondents (56 %) opted for surveillance in cases with low grade dysplasia, with 15 % endoscopically treating the entire section, and 19 % endoscopically ablating select cases. The practice patterns for Barrett’s with high grade dysplasia or early cancer were varied. In total, 37 % of respondents would ablate the entire section of Barrett’s esophagus, with 9 % ablating in select cases. Just under a third of those surveyed would refer patients to a center with expertise in the management of Barrett’s and 20 % would refer directly for a surgical opinion; 2 % of the responses indicated that they would undertake surveillance only.

Table 3. Use of techniques for the eradication of Barrett’s esophagus (n = 163).

| APC | MPEC | RFA | Cryoablation | EMR | |

| BE eradication, % (n) | 41 (67) | 6 (9) | 31 (51) | 5 (8) | 44 (71) |

APC, argon plasma coagulation; MPEC, multipolar electrocoagulation; RFA; radiofrequency ablation; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection.

Comparison between gastroenterologists in community versus university settings

The results were similar across both groups and there were no statistically significant differences.

Comparison between gastroenterologists in Europe and outside of Europe

Responses to the survey were also compared between European-based gastroenterologists and those outside of Europe. For most variables, there were no significant differences between the two groups but European clinicians were statistically more likely to use the Prague C & M classification to describe Barrett’s esophagus (78 % v 41 %, P = 0.0002). There were also more European clinicians using RFA as an eradication technique (46 % v 21 %, P = 0.0153). This was however calculated based on a small sample size (107 of responses; 63 European, 44 outside of Europe).

Practice patterns – independent factors

A multivariate analysis of variance was carried out to see if there were any independent factors in the collected data that predicted practice. No independent factors were found.

Discussion

This study assessed the practice patterns of gastroenterologists in the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Almost half (41 %) of respondents who gave their country of origin were from countries outside of Europe, making this more a survey of worldwide practice. No previous surveys of this kind have been carried out in Europe or the UK and therefore there are no previous studies to draw direct comparisons with. The most comparable recent piece of work is the equivalent study in the United States in which 236 clinicians provided responses 11. It was not possible to calculate a response rate for the survey due to the manner in which it was carried out, and as no demographic data were collected for delegates attending the ESGE learning area, it is not possible to comment on how generalizable our results are. UEGW 2014 was attended by 12 868 delegates from 118 countries, although further demographic data are not available.

The responses to the survey came from 45 different countries and featured a broad range of ages and years of experience, although the majority of respondents were based in university hospitals. Two-thirds of respondents had attended updates on the management of Barrett’s esophagus, fewer than the American figure of 81 %. There was, however, an improved uptake of the Prague C & M classification in our survey, with 60 % of respondents using it compared to only 19 % in the survey from the United States. The subgroup analysis of European clinicians further supports this, although country data were missing for 56 respondents, and it is unknown how these data may have affected the results. It is unclear why the uptake of this classification has been greater in Europe than in the United States, especially as the classification was developed by an international working group with experts from both the United States and Europe. The widespread use of this method of classification, supported by quadrantic biopsy protocols 5 and the use of novel imaging techniques, may be helping the detection of dysplasia and early cancers.

Novel imaging techniques are becoming recognized as beneficial in the detection of dysplasia and early esophageal adenocarcinoma during Barrett’s surveillance. Most clinicians surveyed in the study (73 %) were using advanced imaging techniques either routinely or in specific cases. In the equivalent survey carried out in the United States, 69 % of respondents were using advanced imaging so there has clearly been a large move towards using novel techniques. HD endoscopy was considered an advanced imaging technique in this survey, however, this is becoming more commonplace in routine endoscopy which may explain the high percentages in each survey. Neither this nor the US study specified whether the techniques used were chromoendoscopy or virtual chromoendoscopy, and therefore no assumptions can be made about which was used more commonly. In our study, slightly more clinicians were using advanced imaging techniques in university hospitals than in community hospitals, but this difference was not statistically significant. The use of advanced imaging is thought to enable more specific targeted biopsies to be taken from areas suspicious for dysplasia. A recently reported trial 12 has suggested that taking targeted biopsies using advanced imaging techniques can significantly reduce the number of biopsies taken when compared to the use of the Seattle protocol. This has cost saving implications but the study was limited in that it was performed in expert centers, meaning that the results are not necessarily generalizable.

Surveillance is suggested by major guidelines for the management of non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus. In total, 76 % of the respondents to the survey practiced surveillance in the case of non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus which shows good compliance with guidelines. A minority of clinicians performed eradication of the whole Barrett’s segment with 4 % opting for ablation in select cases. In the American survey, 86 % of respondents practiced surveillance with a minority (12 %) performing ablation.

The most commonly used techniques for eradicating non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus are argon plasma coagulation (APC) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) 7. Both techniques have been shown to be effective at eradicating Barrett’s mucosa although it is still unclear as to whether APC decreases the risk of later cancer development 13. In our survey, there was widespread use of APC (41 % compared to only 4 % in the United States) and RFA (31 % compared to 39 % in the US survey). EMR appears to be much more commonly used in our survey than in the US survey (44 % compared with 17 %) but this may be because our survey was across multiple countries. EMR is recommended as the first technique to use in the removal of visible lesions with subsequent RFA treatment to eradicate the remaining Barrett’s mucosa 9 10 14.

The optimum management of low grade dysplasia associated with Barrett’s esophagus is currently unclear but both the BSG and the ASGE currently recommend that the diagnosis is confirmed by a second pathologist and, if confirmed, repeat endoscopies are performed. The UK guidelines suggest 6 monthly gastroscopies whereas the ASGE guidelines suggest an initial procedure at 6 months and then yearly afterwards. In total, 56 % of clinicians responding to the survey stated they would continue with surveillance, although intervals were not specified in the survey; 19 % of those surveyed suggested they would ablate in select cases, and 15 % practiced ablation in all cases. A recently published trial 14 suggested that eradication of low grade dysplasia with RFA does decrease progression to cancer, although this has yet to be endorsed in guidelines. A meta-analysis of therapy for low grade dysplasia 15, which included this paper, concluded that, although ablation was effective at eradicating dysplastic segments of Barrett’s esophagus, there was not enough evidence to suggest it decreased the risk of progression to adenocarcinoma. The numbers in our survey are comparable to the American survey with the majority of clinicians performing surveillance for low grade dysplasia.

The management of high grade dysplasia and early esophageal adenocarcinomas in Barrett’s esophagus has changed drastically in recent years with endoscopic therapies being preferred to surgery in many cases. In our survey, referral rates to expert centers were similar amongst both community gastroenterologists and those in university hospitals (37 % vs 29 %). Therapeutic ablations were done in 46 % of university settings and 47 % of community settings. More people were referred for surgery from university centers than from community hospitals but the numbers were small. This may be down to patients having already been assessed in an expert university setting and a decision taken that surgery was more appropriate than endoscopic therapy, but the survey did not go into this in detail.

Drawing comparisons between university and community-based clinicians did not reveal any statistically significant differences in our analysis. There was a trend towards clinicians in university settings being more likely to perform EMR but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.0512). This survey was drawn from 45 countries across the world and, as such, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions about differences between community and university practice.

There are some clear limitations to this survey. It was carried out at a single European meeting over the course of 3 days and the response rate was lower than hoped for, despite an incentive being offered. It was not compulsory for respondents to give their country of origin, and only 66 % provided this information. The remaining 34 % of respondents could have been from either Europe or outside of Europe, making it difficult to speculate how relevant the results are to European practice. There were more responses from university-based clinicians than community-based ones making it more difficult to draw comparisons between the two groups from the available data. It is also difficult to estimate how much response bias may be present when people are filling out a survey on a tablet computer with someone watching. Given that the survey was carried out in the ESGE learning area, it is highly likely that the majority of respondents were gastroenterologists with a specific interest in endoscopy. Furthermore, the incentive of free attendance at an ESGE endoscopy event may have attracted more endoscopists. As such, the survey may not accurately represent a true picture of practice.

This survey aimed to investigate the practice patterns of European gastroenterologists in the management of Barrett’s esophagus. However, a large proportion of respondents were from outside of Europe and therefore this survey is best regarded as worldwide practice patterns. The majority of respondents are adhering to published guidelines by practicing surveillance for non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus or cases with low grade dysplasia. Most clinicians are attending courses or meetings on the management of Barrett’s esophagus and there has been reasonable uptake of the Prague C & M criteria amongst clinicians, although an increase on 60 % should be targeted. There is clearly room for improvement with only 40 % of respondents using advanced imaging techniques routinely and a high referral rate for high grade dysplasia to surgery. There were no independent factors identified that predicted practice, and demographic data did not have a bearing on the responses. The data from this study, although limited, suggest a variance in practice patterns across Europe and underline the need for clear guidance and quality assurance standards. ESGE is currently preparing a guideline on the management of Barrett’s esophagus and the results from our survey will help inform this.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank everyone who took part in the survey, and the ESGE team for helping to administer the survey. The survey respondents who asked to be named in any publications are listed below:

Bajram Begaj, Nevila Luli (Albania)

Mariano Marcolongo, Victor Abecia (Argentina)

Adrian Chung, Ahmad Alrubaie (Australia)

Monika Ferlitsch (Austria)

Marakhouski (Belarus)

Mariana Milashka, Marianna Arvanitakis, Raf Bisschops (Belgium)

Naufel Carlos (Brazil)

Feliks Yanev (Bulgaria)

Iacucci Marietta (Canada)

Mirjana Kalauz (Croatia)

Marios Christoforou, Mike Lerios, Nicolaou Panayiota (Cyprus)

Hanne Elisabeth Jense (Denmark)

Alaa Elden Sadek, Ahmed Arnaout, Aladdin Alswaifi, El Ghobary, Hossam Ghoneim, Magdy El-Serafy, Mohamed Gaber, Mohamed Hassan Khalaf, Sherif El Baz, Dr Ashmawy (Egypt)

Pioche (France)

Niedeggen Gottfried Gino (Germany)

Anagnostopoulos Georgios, Fotios Kothonas, Gregorios Paspatis, Katerinis Pantago (Greece)

Boddnar Z, Hritz, Zsolt Dubravcsik (Hungary)

Anuj Sarkari, Takalkar Unmesh, Jaya (India)

Bambang Sutopo (Indonesia)

Afshin Shafaghi, Mohammad Pirouzian, Reza Taslimi, Sadollah Tarakkolibaza (Iran)

Hadi Almasoudi, Rayadh A. Zaydan (Iraq)

Amir Karban (Israel)

Alberto Larghi, Annibale Bruno, Cesare Hassan, Gianluca Rotondano, Graziani Maria Giovanna, Ivo Boskoski, Maria Antonia Bianco, Marina De Matthaeis, Mauro Uggi, Merighi Alberto, Monia Baldoni, Pietro Familiari, Repici Alessandro, Roberto Lorenzetti (Italy)

Hudson Lodenyo (Kenya)

Aida Polloshka, Skender Telaku, Argjira Juniku-Shkololli (Republic of Kosovo)

Lai San Chan (Macao)

Bakkar Meriem, Rouibaa Fedoua, Salwa Oussama (Morocco)

Ravinder Ogra (New Zealand)

Matthew O. Bojuwoye, Pantong Davwar (Nigeria)

Ishaq, Nassr Alsiyabi (Oman)

Haseeb Noor (Pakistan)

Jaaroslaw Regula, Marek Skoczylas (Poland)

Cev Elena, Ion Dina, Madalina Ilie (Romania)

Anastasiia, Elena Abolimova (Russia)

Ishtiaq Ahmed, Mohammed Khan, Mostafa (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia)

Ali (Singapore)

Tatjana Puc Kous, Diana Sanchez, Francisco Jose Garcia Fernandez, Javier Garcia De Paso Mora, Manuel Garcia Rodriguez, Maria Virginia Garcia Alvarez, Marta Cruz Aparicio, Rodrigo Jover (Spain)

Einarsson (Sweden)

Can Gonen, H. Mehmet Sokmen (Turkey)

Bolotskykh Nicolay, Ihor Tumak, Lukavetskyy (Ukraine)

Adil El-nujumi, Sameer Zar (UK)

Saad A. Haque (USA)

Footnotes

Competing interests: Simon Dunn: Research funded by Aquilant Endoscopy. Laura Neilson: Research funded by Aquilant Endoscopy. Prateek Sharma: Grant support from Cook Medical, CDx Labs, Olympus Inc, Cosmo pharma, Takeda Inc. Colin Rees: Research funding from Olympus, Cook, ARC medical and Aquilant endoscopy.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald R C, di Pietro M, Ragunath K. et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63:7–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spechler S J, Sharma P, Souza R F. et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1084–1091. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosetti C, Levi F, Ferlay J. et al. Trends in oesophageal cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1118–1129. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D. et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abela J-E, Going J, Mackenzie J. et al. Systematic four-quadrant biopsy detects Barrett’s dysplasia in more patients than nonsystematic biopsy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:850–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine D, Haggitt R, Blount P. et al. An endoscopic biopsy protocol can differentiate high-grade dysplasia from early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:40–50. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qumseya B J, Wang H, Badie N. et al. Advanced imaging technologies increase detection of dysplasia and neoplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1562–1570.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer J, Laugier R, Chemali M. et al. French Society of Digestive Endoscopy SFED guideline: monitoring of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2007;39:840–842. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phoa K N, Pouw R E, Bisschops R. et al. Multimodality endoscopic eradication for neoplastic Barrett oesophagus: results of an European multicentre study (EURO-II) Gut. 2015 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309298:gutjnl-2015-309298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pech O, May A, Manner H. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for patients with mucosal adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:652–INF. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh M, Gupta N, Gaddam S. et al. Practice patterns among US gastroenterologists regarding endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P, Hawes R H, Bansal A. et al. Standard endoscopy with random biopsies versus narrow band imaging targeted biopsies in Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, international, randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2013;62:15–21. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milashka M, Calomme A, Van Laethem J L. et al. Sixteen-year follow-up of Barrett’s esophagus, endoscopically treated with argon plasma coagulation. UEG J. 2014;2:367–373. doi: 10.1177/2050640614549095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phoa K N, van Vilsteren F G, Weusten B L. et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs endoscopic surveillance for patients with Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1209–1217. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almond L, Hodson J, Barr H. Meta‐analysis of endoscopic therapy for low‐grade dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1187–1195. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]