Abstract

[Purpose] The aim of this study was to translate the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire into Turkish and test its reliability and validity among Turkish pregnant women. [Subjects and Methods] The subjects were 204 healthy, single pregnant women between the ages 18 and 40 who volunteered to participate in this study. Reliability was evaluated by measuring the one-week test-retest reliability with the intraclass correlation coefficient and Pearson’s correlation analysis. Concurrent validity was examined by comparing the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire with the long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and step counts with pedometer. [Results] The mean age of the participants was 28.23±4.94 years, and the mean for BMI was 26.09±4.40. For test-retest reliability, r values were respectively 0.961, 0.934, 0.957 and 0.981 for self-reported sedentary, light, moderate, and vigorous activity, respectively. Intraclass correlation coefficient scores ranged from 0.924 to 0.993. For validity, the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire and long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire ranged from moderate (r = 0.329) to high (r = 0.672). The correlation value between the total score of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire and the step counts was 0.70. [Conclusion] The Turkish version of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire is a valid and reliable tool for measurement of the physical activity level of pregnant women.

Key words: Pregnancy, Physical activity questionnaire, Reliability

INTRODUCTION

Physical activity (PA) has been accepted internationally as an important factor for the protection and improvement of health in pregnant women as well as in the general population1). Recent studies showed the beneficial effects of PA during pregnancy on the risks of gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, hyperlipidemia, preterm birth, excess pregnancy weight gain, and postpartum weight retention2,3,4,5).

Pregnancy is associated with reduced levels of PA due to concerns about adverse fetal and maternal outcomes6). PA varies both over the course of pregnancy and within each trimester. Household and childcare activities contributed more to both moderate-intensity and overall energy expenditure during pregnancy than recreational and sport activities7, 8). In Tukey, the safeness of exercise and amount of exercise required to prevent pregnancy complications, as well as to achieve specific health-related outcomes, are relatively new areas of research.

Measurement of PA is a difficult and complicated process. Valid and reliable methods for measurement of PA are needed to be able to report the duration, frequency, and intensity of PA; to determine the proportion of individuals following health recommendations; to make cross-cultural comparisons; to measure the influence of different intensities of PA on health; and to examine the effects of specific interventions9). The easiest and most common way to measure PA is via self-report or interview based on questionnaires10).

Numerous PA questionnaires have been developed and validated in nonpregnant adults. However, most of these questionnaires fail to include household or childcare activities, which comprise a substantial proportion of PA during pregnancy. Inaccurate determination of the PA level may lead to misunderstandings about the correlations between PA during pregnancy and both maternal and fetal health11,12,13).

The Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ) is a widely used tool for the assessment and measurement of PA levels amongst pregnant women. The PPAQ is a quick and simple method to evaluate the duration, frequency, and intensity of activity patterns in pregnant women. It has been included in both epidemiological and clinical studies11). The PPAQ has already been translated into different languages, and it is available in Japanese, Vietnamese, and French14,15,16). To our knowledge, there are currently no Turkish PA questionnaires that specifically evaluate the PA of pregnant women or take into account the cultural differences of Turkish women.

The purpose of this study was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the English PPAQ to Turkish; to assess the reliability of the Turkish version of the PPAQ in healthy Turkish pregnant women; and to investigate the validity of the Turkish PPAQ by testing its agreement with the long form version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-LF) and a pedometer.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study was performed in two stages: The first stage was cultural and linguistic translation of the PPAQ from English to Turkish, including a pilot study. The second stage was analysis of the statistical reliability and validity of the Turkish PPAQ.

Before the study, contact was established via mail with Lisa Chasan-Taber, and permission was received to adapt the questionnaire. During this translation process, we used a cross-cultural adaptation design that was recommended by Beaton et al17). We established a translation team that consisted of two bilingual physiotherapists (Turkish and English speakers), two native Turkish speaking physiotherapists, and one bilingual native English speaker. The bilingual native English speaker was an English language teacher whose qualifications included a university degree in English. The total number of members on the translation team was five. The original PPAQ was translated from English to Turkish independently and separately by the four physiotherapists. Then the two translations were compared with each other in order to eliminate any possible inconsistency, and a draft Turkish version was produced. The draft translation was then given to the native English speaker to translate back to English. The native speaker was blind to the the original version of the questionnaire and to the purpose of the study. The content of the original and back-translated English versions were compared, and differences were noted. The translation team reviewed all versions. The reviewers commented on the differences, and a synthesis of these differences was created. All materials including the original English, Turkish, back-translated English versions and the synthesis of translation differences were discussed by the translation team. The translation team reached a consensus regarding linguistic imprecision and cultural differences in the Turkish PPAQ.

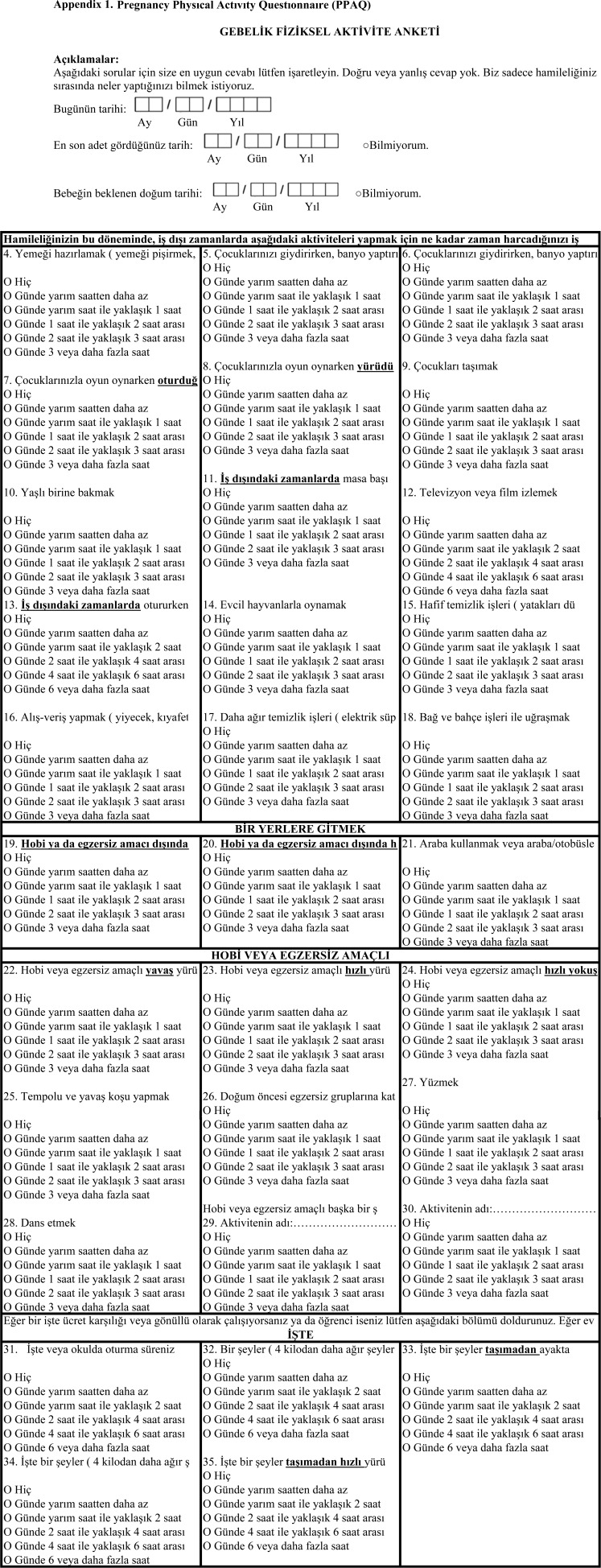

A pilot version of the Turkish PPAQ was completed by ten healthy pregnant volunteers women to determine any misunderstandings and deviations in the translation. The comprehensibility and acceptability of the translation were tested item by item. Following this pilot study, some modifications were made to the final version. Some of the Pas in the orginal version of the PPAQ were not suitable for the Turkish culture, as they were carried out rarely or never by our pilot group, so they were replaced. Two specific examples are items 18 and 19 in the original PPAQ, which refer to the use of a lawnmower; lawnmowers are not commonly used in Turkey, so instead we added an item that addressed “gardening”. Minor changes involved conversion from English Imperial measurements (gallons, pounds) to the metric equivalents (liters, kg) for item 33. While changing the examples of physical activities, we used the compendium of PA to assign an appropriate MET level18, 19). The basic form of the questionnaire was close to the original (Appendix 1).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fatih University and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The present study included 204 healthy, single pregnant volunteers between the ages 18 and 40 who were admitted for routine follow-up to the obstetrics and gynecology unit of Turgut Özal University hospital between July 2012 and October 2014. Participants were excluded if they had any of the following medical conditions: cardiorespiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension requiring medications; chronic renal or inflammatory joint diseases or long-term and/or repetitive musculoskeletal problems that would limit daily PA. Another general exclusion criteria was inability to write and read well enough to record PA. After the screening for general exclusion criteria was complete, demographic characteristics of the participants including employment status and educational level were recorded. We evaluated validity by comparing the PA data from the self-reported PPAQ with the total score of the IPAQ-LF and step counts (7-day averages) measured with a pedometer. The Turkish version of the PPAQ was completed by the all participants first, followed by the IPAQ-LF. Eighty-five participants were then given a pedometer (Geonaute Onstep 100 Pedometer, China) to wear on a belt at the waist during their ordinary daily activities, except during bathing or swimming and sleeping. Pedometers are a useful instrument for objectively assessing PA, and they have been found to provide a valid and reliable measure of ambulatory activity, which is the most prevalent type of activity in life today20). The participants wore the pedometers for one week. PA was evaluated by the average number of steps taken per day over a 7 day period. After one week, the interviewer repeated the questionnaires.

PPAQ is a widely available, self-administered semiquantitative questionnaire for the assessment of PA levels of pregnant women. There are 32 activities, including household/caregiving activities (13), occupational (5), sports/exercise (8), transportation (3), and sedentary activities (3). Participants were asked to select the category best estimating the amount of time spent on an activity per day or week during the current trimester for each activity. The duration ranged from 0 to 6 or more a day and from 0 to 3 or more a week during the current one month. At the end of the PPAQ, an open-ended section allowed the participant to add activities not already listed. From the PPAQ, the number of hours spent in each activity was multiplied by the activity intensity to arrive at a measure of average daily energy expenditure (MET-hours per day) attributable to each activity. Activities were categorized by intensity (i.e., light, moderate, vigorous), type (i.e., household, occupation, sport), or as total activity (sum of all intensity and type scores)11).

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was developed as an instrument for cross-national assessment of PA and for standardizing measures of health-related PA behaviors of populations in many countries and in different sociocultural contexts. The IPAQ is used to assess habitual PA during the past 7 days. There are two versions, the long form (27 items) and the short form (7 items), which can be self-administered or administered during in-person or telephone interviews. The IPAQ used in the present study was the IPAQ-LF. A Turkish version of the IPAQ is available21). Time spent in each activity category was derived by multiplying the number of days per week with the minutes spent doing the activity per day, while total weekly physical activity (MET-Min.week−1) was calculated by multiplying the number of minutes spent in each activity category with the specific MET score for each activity. Scores for walking and for moderate and vigorous activities are the sums of corresponding item scores21).

The statistical analysis of the data was performed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for Windows 15 software. With the sample size of 195, the study had an estimated 99% power to detect a correlation of 0.3 between the score from the questionnaire PPAQ and the number of steps22, 23). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov/Shapiro-Wilk test was used to investigate normality of the distribution of the continuous variables. Variables were normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, all p > 0.05). The descriptive statistics are shown as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as the number of patients and percentage (%) for categorical variables. Reliability was evaluated by measuring the one-week test-retest reliability. Test-retest reliability was determined by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Pearson’s correlation analysis. Concurrent validity was examined by comparing the PPAQ with the IPAQ-LF and step counts with the pedometer. Validity was investigated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and values ≥ 0.40 were considered satisfactory (r ≥ 0.81–1.0 excellent, 0.61–0.80 very good, 0.41–0.60 good, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.0–0.20 poor)24).

RESULTS

The mean age of the participants (N =204) was 28.23±4.94 years, and the mean for BMI was 26.09±4.40. Sixty-seven women were in their first trimester, 81 were in their second trimester, and 56 were in their third trimester. Demographics and characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n=204).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 28.2 (4.9) |

| Gestational age, weeks | 22.5 (11) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m² (SD) | 26 (4.4) |

| Mean prepregnancy BMI, kg/m² (SD) | 23.3 (4.1) |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 15 (7.3) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Full-time housewife | 105 (51.4) |

| On maternity leave | 64 (31.3) |

| Currently employed | 35 (17.1) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Primary school | 30 (14.7) |

| Secondary school | 55 (26.9) |

| High school | 75 (36.7) |

| University | 44 (21.5) |

BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation

The one-week test-retest reliability study was conducted on all participants. The median (25th and 75th percentiles) values (MET.h/wk) for the first and second PPAQ are shown in Table 2. According to Pearson’s correlation analysis for test-retest reliability, the r values were 0.961, 0.934, 0.957, and 0.981 for self-reported sedentary, light, moderate, and vigorous activity, respectively (p<0.001). Overall, the one-week ICC scores ranged from 0.924 to 0.993, with the lowest value recorded for sports/exercise and the highest value for occupational PA. The ICC values were significant for all items on the PPAQ (p < 0.001). The results for test-retest reliability are shown in Table 3.

Table 2. Median (25th and 75th percentile) values (MET.h/wk) for the 1st and 2nd PPAQ.

| 1st PPAQ (MET.h/wk) | 2nd PPAQ (MET.h/wk) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | Median | 75th | 25th | Median | 75th | |

| Total score of PPAQ (light and above) | 146.9 | 209.7 | 324.4 | 145.7 | 225.4 | 320.4 |

| By intensity | ||||||

| Sedentary (<1.5 METs) | 25.5 | 45.2 | 58.1 | 25.9 | 41.2 | 55.1 |

| Light (1.5≤3.0 METs) | 95.1 | 151.4 | 195.3 | 95.5 | 137.9 | 182.4 |

| Moderate activity (3.0–6.0 METs) | 22.4 | 61.2 | 138.2 | 23 | 61.2 | 128.9 |

| Vigorous activity (>6.0 METs) | 0 | 0 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 11.3 |

| By type | ||||||

| Household/caregiving | 95.5 | 161.7 | 232.4 | 92 | 141.3 | 232.4 |

| Occupational activity | 0 | 0 | 74.2 | 0 | 0 | 73.8 |

| Sports/exercise | 5.6 | 16.8 | 56.9 | 3.9 | 20 | 54.5 |

PPAQ: Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire; MET: metabolic energy turnover. **p<0.001

Table 3. Results of for the test-retest reliability of the PPAQ.

| Test–retest reliability | ||

|---|---|---|

| ICC (95% CI) | r (95% CI) | |

| Total score of PPAQ | 0.950 (0.914–0.971) | 0.947 (0.925–0.963)** |

| By intensity | ||

| Sedentary (<1.5 METs) | 0.961 (0.933–0.978) | 0.961 (0.945–0.972)** |

| Light (1.5≤3.0 METs) | 0.934 (0.886–0.962) | 0.934 (0.906–0.953)** |

| Moderate activity (3.0–6.0 METs) | 0.956 (0.923–0.975) | 0.957 (0.939–0.970)** |

| Vigorous activity (>6.0 METs) | 0.979 (0.963–0.988) | 0.981 (0.973–0.986)** |

| By type | ||

| Household/caregiving | 0.959 (0.929–0.977) | 0.961 (0.945–0.972)** |

| Occupational activity | 0.993 (0.988–0.996) | 0.993 (0.990–0.995)** |

| Sports/exercise | 0.924 (0.870–0.956) | 0.927 (0.896–0.949)** |

PPAQ: Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire; r: Pearson’s correlation coefficients; CI: confidence interval; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; MET: metabolic energy turnover. **p<0.001

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the PPAQ and IPAQ-LF ranged from moderate (r = 0.329) to high (r = 0.672), indicating good convergent validity for the Turkish PPAQ. The total PA score of the Turkish version of the PPAQ was significantly and highly correlated with the total PA (MET-min week−1) from the IPAQ-LF (r = 0.672, p < 0.001). Also, the time (Min week−1) spent in sitting from the IPAQ-LF was significantly (r = −0.653, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with the sedentary PA score of the Turkish version of the PPAQ. The correlation coefficients between all items of the PPAQ and the IPAQ-LF are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. The correlation coefficients between the PPAQ and the IPAQ-LF and pedometer.

| Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) for the PPAQ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | Sedentary activity | Light activity | Moderate activity | Vigorous activity | Household/caregiving | Occupational activity | Sports/exercise | ||

| IPAQ-LF | Total PA | 0.672** | −0.114 | 0.345** | 0.375** | 0.041 | 0.389** | 0.110 | 0.085 |

| Vigorous PA | 0.015 | −0.098 | 0.111 | 0.019 | 0.421** | 0.052 | 0.025 | 0.015 | |

| Moderate PA | 0.352** | −0.121 | 0.186 | 0.378** | 0.118 | 0.419** | 0.121 | 0.102 | |

| Walking PA | 0.418** | −0.145 | 0.329** | 0.085 | 0.053 | 0.343** | 0.114 | 0.344** | |

| Occupational PA | 0.143 | −0.131 | 0.135 | 0.097 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.344** | 0.027 | |

| Transportation PA | 0.096 | −0.148 | 0.186 | 0.115 | 0.031 | 0.052 | 0.033 | 0.042 | |

| House-yard work PA | 0.438** | −0.096 | 0.335** | 0.430** | 0.104 | 0.517** | 0.135 | 0.039 | |

| Leisure time PA | 0.051 | −0.084 | 0.394** | 0.074 | 0.012 | 0.089 | 0.012 | 0.356** | |

| Sitting time, min | −0.096 | −0.653** | −0.201 | −0.023 | −0.006 | −0.012 | −0.093 | −0.015 | |

| Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for the total PPAQ score | |||||||||

| Step counts with pedometer (7 day) | 0.700** | ||||||||

PPAQ: Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire; IPAQ-LF: long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire; PA: physical activity. **p<0.001

The participants took an average of 3249 (range, 646 to 7685; SD, 2129) steps per day, accumulating an average of 22744 (range, 4525 to 53797; SD, 14907) steps during the 7-day monitoring period. When the correlation between the PPAQ and step counts was investigated, the r value was 0.70 (p<0.001) for the total score of the PPAQ (Table 4). These results showed convergent validity of the Turkish version of the PPAQ.

DISCUSSION

The study’s results suggests that the Turkish version of the PPAQ is a reliable and valid tool for assessing PA in Turkish pregnant women.

The availability of the questionnaire in several languages facilitates universality of results from clinical trials. Adequate translation procedures have to be used to achieve cross-cultural equivalence when translating patient-reported outcome measures such as PA questionnaires. The results of our reliability and validity testing are in line with those of previous studies, which is evidence that our translation procedure was adequate.

ICCs can range from 0.00 to 1.00, with values of 0.60 to 0.80 regarded as evidence of good reliability and those above 0.80 indicating excellent reliability25). In our study, the ICCs were above 0.80, indicating that the Turkish PPAQ has excellent reliability.

The reliability of the PPAQ has been addressed in a few studies. Chasan-Taber et al.11), who developed the questionnaire, administered the PPAQ to 54 pregnant women aged 16 to 40 to assess its one-week reliability and found ICCs of 0.78, 0.79, 0.78, 0.82, 0.81, 0.86, 0.93, and 0.83 for total, sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous, household/caregiving, occupational, and sports/exercise activity, respectively. Similarly, in the Vietnamese version of the PPAQ, the ICC value was 0.88 for total activity, 0.94 for sedentary activity, 0.88 for light activity, 0.90 for moderate activity, and 0.87 for vigorous activity14). Chandonnet et al.16) reported that the ICCs for the French version of the PPAQ were 0.90 for total activity, 0.86 for light and moderate-intensity activity, and 0.81 vigorous-intensity activity. In the Japanese version, the ICCs were ≥0.56 for total activity and other activity categories15). In our study, the one week ICC value was 0.95 for total activity, 0.96 for sedentary activity, 0.93 for light activity, 0.95 for moderate activity, and 0.97 for vigorous activity, and we found that the ICCs were 0.95, 0.99, and 0.92 for household/caregiving, occupational, and sports/exercise activity, respectively. We also computed correlation coefficients for test-retest reliability and found that the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.927 to 0.993. All of these results are similar to our results indicating successful adaptation of the PPAQ to Turkish culture and excellent reliability of the Turkish PPAQ.

When comparing our results for PA levels with those of other countries around the world, we found that the total activity scores of Turkish pregnant women were higher than those in America, Canada, and Vietnam. We found that the most significantly higher activity score was for household/caregiving activities. In the original, French, and Japanese versions, a uniaxial accelerometer was used to establish validity11, 15, 16). We used a pedometer and the IPAQ-LF for establishing validity. Analysis of activity intensity was not possible with the pedometer, as it only reflects the total activity. But the use of pedometers combined with a PA questionnaire has been shown to be a useful tool for assessing the validity of PA26).

Chasan-Taber et al.11) reported Spearman correlations between the PPAQ and three published cut points used to classify actigraph data that ranged from 0.08 to 0.43 for total activity, 0.25 to 0.34 for vigorous activity, 0.20 to 0.49 for moderate activity, and 0.08 to 0.22 for light-intensity activity. In a study of the French version of the PPAQ, the authors reported that the correlations between the PPAQ and accelerometer counts were 0.58 for total activity, 0.39 for vigorous activity and 0.49 for moderate activity16). In a study of the Vietnamese version of the PPAQ, the authors used a pedometer for validity assessment as we did in our study, and they reported moderate correlations (0.29) between the PPAQ and the pedometer14). In our study, we found high correlation (0.70) between the PPAQ and pedometer.

To our knowledge, there is currently no study in the literature that has used the IPAQ-LF to investigate the validity of the PPAQ. We used the IPAQ-LF because it has been widely used in PA research and was designed to make cross-national comparisons possible27). In our study, we found that the correlation ranged from moderate to high between the PPAQ and IPAQ-LF. The results of our validation study indicated the following correlation values between the total score of the IPAQ-LF and PPAQ: was 0.672 for the total score of the PPAQ, 0.352 for light activity, 0.375 for moderate activity, and 0.389 for household/caregiving activity. But there was no correlation between the total score of the IPAQ-LF and the sedentary and vigorous activity scores of the PPAQ.

Our study has some limitations. First, the pedometer does not detect upper body movement such as pushing, lifting, or carrying something. Moreover, swimming activities were not counted, as the pedometer has to be removed when in water. Nevertheless, pedometers are technically reliable and objective methods for assessing PA and they were used as a comparison measure for assessment of the convergent validity of the questionnaires. Also, self-report measures of PA are limited by factors including social desirability, recall bias, and variations in cognitive and memory processes depending on several factors including age, education, occupational status, and socioeconomic position. Despite these limitations, strengths of our study are the use of two validation measures, the one-week test-retest repeatability design, and our sample size.

In conclusion, recent health strategies encourage 30 minutes per day of moderate-intensity activities 5–7 days per week in pregnant women. There is a need for accurate assessment techniques to measure all domains of PA to ensure pregnant women are achieving this objective. The translated and cross-culturally adapted form of the Turkish PPAQ may provide an important perspective for preventing pregnancy complications and maintaining a healthy life for both the mother and baby.

Appendix 1

Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire

REFERENCES

- 1.Brooks GA, Butte NF, Rand WM, et al. : Chronicle of the Institute of Medicine physical activity recommendation: how a physical activity recommendation came to be among dietary recommendations. Am J Clin Nutr, 2004, 79: 921S–930S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guelinckx I, Devlieger R, Mullie P, et al. : Effect of lifestyle intervention on dietary habits, physical activity, and gestational weight gain in obese pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2010, 91: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dempsey JC, Sorensen TK, Williams MA, et al. : Prospective study of gestational diabetes mellitus risk in relation to maternal recreational physical activity before and during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol, 2004, 159: 663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Lee IM, et al. : Recreational physical activity during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Hypertension, 2003, 41: 1273–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajjimaporn A, Somprasit C, Chaunchaiyakul R: A cross-sectional study of resting cardio-respiratory and metabolic changes in pregnant women. J Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26: 779–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke PE, Gross H: Women’s behaviour, beliefs and information sources about physical exercise in pregnancy. Midwifery, 2004, 20: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer MS, McDonald SW: Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2006, 3: CD000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zavorsky GS, Longo LD: Exercise guidelines in pregnancy: new perspectives. Sports Med, 2011, 41: 345–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmerhorst HJ, Brage S, Warren J, et al. : A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 2012, 9: 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makabe S, Makimoto K, Kikkawa T, et al. : Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH) scale in older adults. J Phys Ther Sci, 2015, 27: 517–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, et al. : Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2004, 36: 1750–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borodulin KM, Evenson KR, Wen F, et al. : Physical activity patterns during pregnancy. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2008, 40: 1901–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison CL, Thompson RG, Teede HJ, et al. : Measuring physical activity during pregnancy. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 2011, 8: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ota E, Haruna M, Yanai H, et al. : Reliability and validity of the Vietnamese version of the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ). Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, 2008, 39: 562–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuzaki M, Haruna M, Nakayama K, et al. : Adapting the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire for Japanese pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs, 2014, 43: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandonnet N, Saey D, Alméras N, et al. : French Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire compared with an accelerometer cut point to classify physical activity among pregnant obese women. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7: e38818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. : Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 2000, 25: 3186–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. : Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2000, 32: S498–S504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kriska A: Ethnic and cultural issues in assessing physical activity. Res Q Exerc Sport, 2000, 71: 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Masurier GC, Tudor-Locke C: Comparison of pedometer and accelerometer accuracy under controlled conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2003, 35: 867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saglam M, Arikan H, Savci S, et al. : International physical activity questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Turkish version. Percept Mot Skills, 2010, 111: 278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM, et al. : Measurement of physical activity to assess health effects in free-living populations. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1993, 25: 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachin JM: Introduction to sample size determination and power analysis for clinical trials. Control Clin Trials, 1981, 2: 93–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkwood BR, Sterne JA: Essential medical statistics, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004, pp 430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portney LG, Watkins MP: Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. East Norwalk CT: Appleton Lange, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sequeira MM, Rickenbach M, Wietlisbach V, et al. : Physical activity assessment using a pedometer and its comparison with a questionnaire in a large population survey. Am J Epidemiol, 1995, 142: 989–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Holle V, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Deforche B, et al. : Assessment of physical activity in older Belgian adults: validity and reliability of an adapted interview version of the long International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-L). BMC Public Health, 2015, 15: 433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]