Healthcare worker's willingness to care for Ebola patients did not precisely mirror their beliefs about the ethics of refusing to provide care, they were strongly influenced by concerns about potentially exposing families and friends to Ebola virus disease.

Keywords: Ebola, ethics, healthcare workers

Abstract

Background. We assessed healthcare workers' (HCWs) attitudes toward care of patients with Ebola virus disease (EVD).

Methods. We provided a self-administered questionnaire-based cross-sectional study of HCWs at 2 urban hospitals.

Results. Of 428 HCWs surveyed, 25.1% believed it was ethical to refuse care to patients with EVD; 25.9% were unwilling to provide care to them. In a multivariate analysis, female gender (32.9% vs 11.9%; odds ratio [OR], 3.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–7.7), nursing profession (43.6% vs 12.8%; OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.4–5.2), ethical beliefs about refusing care to patients with EVD (39.1% vs 21.3%; OR, 3.71; 95% CI, 2.0–7.0), and increased concern about putting family, friends, and coworkers at risk (28.2% vs 0%; P = .003; OR, 11.1) were independent predictors of unwillingness to care for patients with EVD. Although beliefs about the ethics of refusing care were independently associated with willingness to care for patients with EVD, 21.3% of those who thought it was unethical to refuse care would be unwilling to care for patients with EVD. Healthcare workers in our study had concerns about potentially exposing their families and friends to EVD (90%), which was out of proportion to their degree of concern for personal risk (16.8%).

Conclusion. Healthcare workers' willingness to care for patients with Ebola patients did not precisely mirror their beliefs about the ethics of refusing to provide care, although they were strongly influenced by those beliefs. Healthcare workers may be balancing ethical beliefs about patient care with beliefs about risks entailed in rendering care and consequent risks to their families. Providing a safe work environment and measures to reduce risks to family, perhaps by arranging child care or providing temporary quarters, may help alleviate HCW's concerns.

The public's reaction to the threat of Ebola virus mirrored that of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic when it first surfaced. Similar to Ebola virus, there were no effective management options when HIV first emerged, and both diseases had poor prognoses. Because healthcare facilities provide care to patients during any epidemic, healthcare workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of contracting infection, and not all HCWs have willingly accepted that obligation. In fact, during the 1980s, there were many publicized examples of providers distancing themselves from AIDS patients, leading the Surgeon General to publically assail those who were refusing to provide care and denouncing them as a “fearful and irrational minority” who were guilty of “unprofessional conduct.” It was during that period that the highly sensitive issues of law, ethics, morality, and social cohesion came to the forefront. In 1988, a seminal article was published reporting the degree to which physicians felt that it would be ethical to deny care to patients with AIDS [1]. Slightly more than one quarter of a century later, in the fall of 2014, the world's attention turned to Ebola, and a level of concern similar to that which had been seen in regard to AIDS in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era could again be seen in the lay press [2–4]. Not as much attention has been paid to whether physicians' attitudes towards Ebola mirror those of physicians in the 1980s in regard to AIDS.

The biology and epidemiology of Ebola virus disease (EVD) have become increasingly well understood. Once infection is established in humans, Ebola virus can be transmitted person-to-person by direct contact of skin or mucous membranes with blood or body fluids of infected patients, contaminated objects (eg, needles), or the bodies of individuals who died with EVD. Of note, Ebola virus does not appear to spread by airborne route in the endemic setting, and infected individuals are only capable of disease transmission after the development of symptoms. Despite this enhanced understanding, there are still concerns about the health risks posed to contacts of patients infected with Ebola, including threats to HCWs. The infection of HCWs in Texas who provided care to the first Ebola patient in the United States fueled that concern [5, 6]. Of the four cases of Ebola diagnosed in the United States, only two were acquired by transmission within the United States. Both cases were nurses (diagnosed on October 10, 2014 and October 15, 2014, respectively) who cared for the first case of Ebola (diagnosed on 30 September 2014) in the United States, a man who had traveled to Dallas, Texas from Liberia. The fourth and last case in the United States (diagnosed October 23, 2014) was also a medical aid worker who had returned to New York City from Guinea, after serving with Doctors Without Borders. In the wake of those cases, a massive training program and the organization of a triage system among hospitals were undertaken in the United States.

Despite (or perhaps, ironically, because of) those efforts, anxiety about the Ebola epidemic may be prevalent among HCW. However, despite a rich literature regarding physicians' concerns about HIV written during the 1980s, only limited assessments of HCWs' attitudes towards Ebola have been published. One recent study was written before any cases were reported in the United States, and it focused primarily on HCWs' knowledge and exclusively on pediatric providers [7]. Any hesitancy by HCWs in general to render care to patients with Ebola would have both ethical and public health consequences. Therefore, we assessed HCWs' attitudes toward the care of patients infected with the Ebola virus. To do so, we used an approach similar to one that had been used in one of the key studies from the 1980s that assessed attitudes of healthcare providers towards AIDS patients, and we conducted surveys using self-administered questionnaires at two hospitals; one that was a designated Ebola center and one that was not. The former hospital was also one of the sites of the earlier study by Link et al [1] on attitudes toward care of AIDS patients.

METHODS

After approval by our Institutional Review Board (IRB), a self-administered, questionnaire-based study was performed to assess HCWs' willingness to care for patients with Ebola patients, their concerns about acquiring Ebola from their patients, and their ethical beliefs regarding refusal to render care to such patients. The study was carried out at two sites in New York City between December 2014 and April 2015. The survey was anonymous and consisted of 15 multiple choice questions that included information on demographics, occupation, willingness to care for patients with Ebola, and respondents' perspective on the healthcare system's level of readiness. There were also questions asking whether the respondents thought it was ethical to refuse care to patients with Ebola and to patients with HIV/AIDS. Finally, there were two brief vignettes to assess the participants' willingness to intervene as healthcare providers, outside of the hospital, to help individuals found bleeding on the street, one of whom wore a T-shirt that said “Proud to be a Liberian.” We piloted the questionnaire on 10 subjects to make sure that it was understandable and not burdensome in terms of time. No changes were necessary based on the feedback, and no surveys from the pilot were included in the analysis. The average time to complete the survey during the pilot was four minutes. The questionnaire was administered by two of the authors (D.M.N. and D.B.) to healthcare providers (physicians, residents, medical students, physician assistants, registered nurses and midwifes) who filled it out in private and then returned it to the authors. We recruited HCWs from various departments (Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology) practicing in varied settings (Emergency rooms, Inpatient floors, Outpatient clinics, Labor floor).

The study was designed as a cross-sectional study to be conducted at both hospitals simultaneously, but due to local IRB clearance and administrative delays, recruitment at hospital B occurred more frequently in the latter portion of the recruitment period. Because it is possible that attitudes might have evolved over time, as concerns about the Ebola epidemic waned, we considered time of administration of the survey as a confounder in the analysis.

We hypothesized that the proportion of HCWs who would be unwilling to care for patients with Ebola would be the same as the proportion of HCWs unwilling to care for patients with HIV/AIDS in the 1980s (25%). Given a projected prevalence of 25%, for a 95% 2-sided confidence interval (CI) around that estimate with a width of ±5 percentage points, the required sample size was 289 participants. Because we also wanted to consider time as a confounder, we recruited in excess of this number.

Standard descriptive statistics were used to describe the data. Two-way frequency tables were generated to gauge strength of association of Ebola care outcomes (ethical beliefs and willingness to provide care for patients with Ebola) with demographics and other predictors. Associations of apparent interest in these tables were selected for further examination using regression modeling: multiple logistic regression was used to predict each (dichotomized) care outcome in a separate model. Details on the variables used in each logistic regression model and dichotomization of the variables are described in the tables. Likelihood ratio test P values for type III analyses and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with CIs for regression parameter estimates significant at P < .05 are reported. McNemar tests were used (1) to compare prevalence of ethical beliefs on refusing care to EVD compared with HIV patients and (2) to compare the extent to which HCWs were willing to help individuals found bleeding on the street, one of whom wore a T-shirt that said “Proud to be a Liberian”.

RESULTS

Of 514 HCWs approached for participation, 428 (83.3%) completed the survey; their demographics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 39.9 years (standard deviation, 12.1), most were female (68.2%) and most lived with family (73.8%). Nurses comprised the largest group surveyed (41.2%) followed by attending physicians (31.8%). The HCWs' perspectives on Ebola are shown in Table 2. One fourth of the participants (25.1%) believed that it was ethical to refuse to care for patients with Ebola, and a similar proportion (25.9%) were “somewhat” or “very unwilling” to provide care for a patient with Ebola. For patients with HIV/AIDs, 12.6% of participants thought it was ethical to refuse care, which was significantly less than the proportion of participants who thought that it was ethical to refuse care to EVD patients (P < .001).

Table 1.

Demographics

| Demographics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 39.9 (12.1)a |

| Gender | |

| Male | 135 (31.8) |

| Female | 289 (68.2) |

| Current status | |

| Attending physician | 133 (31.8) |

| Resident physician | 93 (22.2) |

| Nurse | 172 (41.2) |

| Others | 20 (4.8) |

| Department | |

| Internal medicine | 121(29) |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 168 (40.3) |

| Emergency Medicine | 128 (30.7) |

| Living situation | |

| Not living with family | 112 (26.2) |

| With family—no children | 106 (24.8) |

| With family—with children | 209 (49) |

| Time of survey | |

| Initial surveys: Until the end of 2014 | 162 (37.8) |

| Later surveys: After the beginning of 2015 | 266 (62.2) |

| Hospital | |

| Hospital A | 283 (66.1) |

| Hospital B | 145 (33.9) |

a Mean (standard deviation).

Table 2.

Healthcare Workers Perspectives on EVD

| Healthcare Workers Perspectives on Ebola | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Think that the healthcare system in your hospital well equipped to deal with Ebola | 174 (44.1) |

| How often have you worried about contracting Ebola from a patient? | |

| Never/Once in a while | 353 (83.2) |

| Quite often/All the time | 71 (16.8) |

| Has the concern of acquiring Ebola as a result of patient care added to your stress level? | |

| Not at all/Very little | 333 (78.7) |

| Quite a bit/A lot | 90 (21.3) |

| If you had provided care to a patient with Ebola yesterday and you were currently asymptomatic, how concerned would you be that you would put your family/friends/coworkers at risk of Ebola? | |

| Not at all concerned | 39 (9.2) |

| Somewhat/Very concerned | 387 (90.8) |

| How willing would you be to provide care for a patient with Ebola if the care required by the patient is in your field of expertise? | |

| Always/somewhat willing to treat | 240 (56.1) |

| Neutral | 77 (18) |

| Somewhat/very unwilling to treat | 111 (25.9) |

| Think it is ethical to refuse to provide care for Ebola patients. | 105 (25.1) |

| Think it is ethical to refuse to provide care for patients with HIV/AIDS. | 53 (12.6) |

| Agree with a mandated quarantine of asymptomatic healthcare workers returning from West Africa. | 276 (66.7) |

| Agree with a mandated quarantine of asymptomatic healthcare workers caring for Ebola patients in the United States. | 250 (59.8) |

| Will help a young boy lying on the street, unconscious and bleeding by compressing the bleeding area with your bare hands (no protective equipment). | 183 (43.9) |

| Will help a middle-aged man wearing a T-shirt that said “proud to be a Liberian” lying on the street, unconscious and bleeding by compressing the bleeding area with your bare hands (no protective equipment). | 124 (30) |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; EVD, Ebola virus disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Only 44.1% of participants felt that their hospital was well equipped to take care of patients with Ebola. A total of 16.8% of HCWs worried “quite often” or “all the time” about contracting Ebola from a patient, and 21.3% felt that concern about acquiring Ebola as a result of patient care had added to their stress level “quite a bit” or “a lot.” If they had provided care to a patient with Ebola, 90.8% of participants would be “somewhat” or “very concerned” about putting their family, friends, and coworkers at risk of Ebola even if they (the HCW) were asymptomatic. A total of 43.9% of participants would help a young boy found bleeding on the street despite not having any protective equipment, but only 30% would help a man in a similar situation if he were wearing a T-shirt that said “Proud to be a Liberian.” This difference was statistically significant (P < .001).

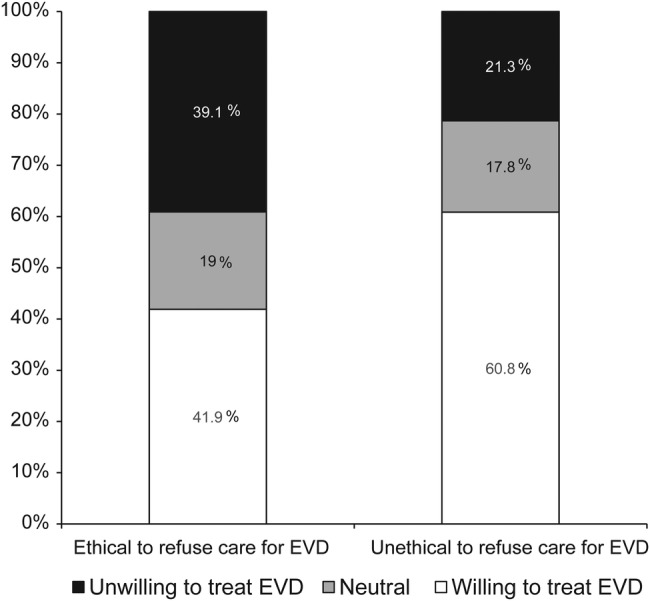

In a multivariate analysis, female gender (32.9% vs 11.9%; OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.4–7.7), nursing profession (43.6% vs 12.8%; OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.4–5.2), ethical beliefs about refusing care to patients with EVD (39.1% vs 21.3%; OR, 3.71; 95% CI, 2.0–7.0), and increased concern about putting family, friends, and coworkers at risk (28.2% vs 0%; P = .003; OR, 11.1) were independent predictors of unwillingness to care for patients with Ebola (Table 3). Although beliefs about the ethics of refusing care were independently associated with willingness to care for patients with Ebola, 41.9% of those who thought it was ethical to refuse care would still be willing to care for patients with Ebola, whereas 21.3% of those who thought it was unethical to refuse care would be unwilling to do so (Figure 1). We did not find any variables that independently predicted beliefs about whether it is ethical to refuse to care for patients with Ebola (Table 4).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis, Unwillingness to Care for EVDa

| Variable | Somewhat/Very Unwilling to Care for EVD |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Value, AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 40.4 (11.2)b | |

| Genderc | ||

| Female | 95 (32.9) | P = .004; OR, 3.2 (1.4–7.7) |

| Male | 16 (11.9) | |

| Current statusc | ||

| Nurse | 75 (43.6) | P = .002; OR, 2.7 (1.4–5.2) |

| Physicians (Attending and Resident physicians) | 29 (12.8) | |

| Department | ||

| Internal medicine | 24 (19.8) | |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 51 (30.4) | |

| Emergency Medicine | 31 (24.2) | |

| Living situationc | ||

| Not with family | 17 (15.2) | P = .064 |

| With family—no children | 23 (21.7) | |

| With family—with children | 71 (34) | |

| Hospital equipped to deal with Ebolac | ||

| Yes | 30 (17.2) | P = .091 |

| No | 70 (31.7) | |

| Worried about contracting Ebolac | ||

| Never/Once in a while | 80 (22.7) | P = .860 |

| Quite often/All the time | 28 (39.4) | |

| Concern about putting family/friends/coworkers at riskc | ||

| Somewhat/Very concerned | 109 (28.2) | P = .003; OR, 11.1d |

| Not at all concerned | 0 (0) | |

| Ethical to refuse care for Ebolac | ||

| Yes | 41 (39.1) | P < .001; OR, 3.7 (2.0–7.0) |

| No | 67 (21.3) | |

| Ethical to refuse care for HIV/AIDS | ||

| Yes | 17 (32.1) | |

| No | 89 (24.3) | |

| Time of survey | ||

| Initial: Until the end of 2014 | 47 (29) | |

| Later: After the beginning of 2015 | 64 (24.1) | |

| Hospital | ||

| Hospital A | 81 (28.6) | |

| Hospital B | 30 (20.7) | |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; EVD, Ebola virus disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

a Variables with more than 2 responses have been dichotomized as follows in the logistic regression: Living situation: With children vs Not with family/With family—no children. Worried about contracting Ebola: Never/Once in a while vs Quite often/All the time. Concern about putting family/friends/coworkers at risk: Somewhat/Very concerned vs Not at all concerned. The P values are provided for all variables used in the logistic regression, OR and CIs are provided only when the P values were significant.

b Mean (standard deviation).

c Variables included in the logistic regression.

d Confidence interval not reported due to sampling zero.

Figure 1.

Relationship between ethical beliefs on refusal to care for Ebola virus disease (EVD) patients and unwillingness to care for them.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis, Ethical to Refuse Care for EVDa

| Variable | Ethical to Refuse Care for EVD |

|

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P Value | |

| Age | 38 (11.1)b | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 (22.4) | |

| Female | 75 (26.6) | |

| Current statusc | ||

| Nurse | 50 (29.9) | P = .994 |

| Physicians (Attending and Resident physicians) | 51 (22.9) | |

| Department | ||

| Internal medicine | 22 (18.6) | |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 42 (25.5) | |

| Emergency Medicine | 39 (30.7) | |

| Living situation | ||

| Not with family | 28 (26.2) | |

| With family—no children | 25 (24.3) | |

| With family—with children | 51 (24.8) | |

| Hospital equipped to deal with Ebola | ||

| Yes | 40 (23.3) | |

| No | 54 (25.1) | |

| Worried about contracting Ebolac | ||

| Never/Once in a while | 77 (22.2) | P = .541 |

| Quite often/All the time | 27 (39.7) | |

| Concern about putting family/friends/coworkers at riskc | ||

| Not at all concerned | 7 (18.4) | P = .957 |

| Somewhat/very concerned | 97 (25.6) | |

| Ethical to refuse care for HIVc | ||

| Yes | 26 (49.1) | P = .352 |

| No | 77 (21.5) | |

| Time of survey | ||

| Initial: Until the end of 2014 | 42 (26.3) | |

| Later: After the beginning of 2015 | 63 (24.3) | |

| Hospital | ||

| Hospital A | 75 (27.1) | |

| Hospital B | 30 (21.1) | |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; EVD, Ebola virus disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Variables with more than 2 responses have been dichotomized as follows in the logistic regression: Worried about contracting Ebola: Never/Once in a while vs Quite often/All the time. Concern about putting family/friends/coworkers at risk: Somewhat/Very concerned vs Not at all concerned. The P values are provided for all variables used in the logistic regression.

b Mean (standard deviation).

c Variables included in the logistic regression.

Female gender (60.9% vs 44.8%; OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.01–2.6) and increased concern about contracting Ebola (76.1% vs 52%; OR, 2.7; 95 CI, 1.4–5) were also independently associated with unwillingness to help a bleeding young boy without protective equipment, whereas concern about putting family, friends, and coworkers at risk (71.9% vs 50%; OR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.08–4.5) was the only predictor independently associated with unwillingness to help a man in a similar situation when he was wearing a T-shirt that said “Proud to be a Liberian.”

DISCUSSION

With a record number of healthcare workers affected in the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, and the failure of personal protective equipment in Dallas leading to EVD in a HCW, there has been increased concern among HCWs in the United States about their personal safety while treating patients with Ebola. Indeed, when the first Ebola patient in New York was admitted to Bellevue hospital, an extraordinary number of its staff called out sick; one of the nurses went so far as to pretend she had a stroke [8, 9]. We have found, in a survey of 428 HCWs in large urban hospitals, that one fourth of HCWs were unwilling to care for Ebola patients, and a similar proportion believed that it was ethical to refuse to care for patients with EVD. This is comparable to what was seen with HIV in the 1980s in the study by Link et al [1], in which 25% of HCWs would not continue to care for AIDS patients if given a choice and 24% believed that it was ethical to refuse care to patients with HIV/AIDS. Almost three decades later, with increased knowledge and improved prognosis for HIV patients after the advent of HAART, only 12.6% of HCWs in our study believed that it was ethical to refuse care to patients with HIV/AIDS. As knowledge of the pathophysiology and epidemiology of EVD and its implications for healthcare providers become more widely disseminated, it is hoped that a similar evolution may take place for EVD.

Our findings are in concert with and extend those reported by Highsmith et al [7], who found, in a survey of 245 pediatric HCWs at a single institute, that only 80% of participants were willing to examine patients with EVD, and 64%–79% were willing to perform procedures on them. That survey was conducted before the first documented case of EVD was reported in the United States, and the factors that influenced the pediatricians' unwillingness to care for patients with EVD were not explored. The study focused mainly on HCWs' knowledge of Ebola transmission and epidemiology, and it found that the knowledge scores were poor (56%).

A question that arises in light of those findings and ours is, what are physicians' obligations to society to care for patients with EVD, and, pari passu, what are society's obligations to physicians? The question of whether there is a duty to treat even when providing care puts the HCW at risk has been addressed by professional organizations whose guidelines suggest that although there is a professional obligation, it is not absolute [10]. The American Medical Association Code of Ethics states that “Because of their commitment to care for the sick and injured, individual physicians have an obligation to provide urgent medical care during disasters. This ethical obligation holds even in the face of greater than usual risks to their own safety, health or life. The physician workforce, however, is not an unlimited resource; therefore, when participating in disaster responses, physicians should balance immediate benefits to individual patients with ability to care for patients in the future” [11]. It could be argued that society also has an obligation (1) to provide a safe work environment and (2) to make arrangements to adequately care for and compensate HCWs who become infected in the course of duty. Less than half of the participants in our study believed that their institution was well equipped to take care of patients with Ebola. Healthcare workers' concerns about acquiring Ebola are exacerbated by concerns regarding their options if they were to get infected while treating an Ebola patient and if, for example, they wanted to get short-term life insurance [12].

We found that although beliefs about the ethics of refusing care were independently associated with willingness to care for patients with Ebola, 41.9% of those who thought it was ethical to refuse care would still be willing to care for patients with Ebola, whereas 21.3% of those who thought it was unethical to refuse care would be unwilling to care for patients with Ebola (Figure 1). In other words, beliefs about the “right thing to do” do not always determine what people are willing to do. Less knowledge about the disease is one possible explanation of why nurses were more likely to be unwilling to care for patients with Ebola than physicians. In a survey of pediatric HCWs performed before the first case of Ebola was diagnosed in the United States, knowledge scores about Ebola were higher among those willing to care for patients with Ebola, and physicians scored higher than nonphysicians [7]. In regard to HCWs' reticence to render assistance outside the hospital, it is possible that it reflects more than just fears about Ebola because concerns about other infections such as HIV and hepatitis C virus, particularly when personal protective equipment is not available, are certainly reasonable. However, we did see an even greater reticence when the individual needing assistance wore a T-shirt identifying himself as Liberian, suggesting both that profiling may be at play, and, given that his infection status was unknown, that a person need not be infected with Ebola to receive lesser care because of it.

In a study of attitudes towards patients with HIV, published one quarter century ago, the authors called for greater education about HIV [1]. Our data suggest that concerns voiced about HIV are not sui generis and that each generation may have to confront their own fears about the risks inherent in the practice of medicine. Therefore, some teaching may need to go beyond the unique biology, and infection control necessities associated with a given infectious agent, and instead focus on the broader issue of the ethical responsibilities, and limits thereupon, of physicians in the face of epidemics. There is also a need for institutions to demonstrate concerns about their employees and take steps to minimize risks. If the word “Ebola” was substituted for the word “AIDS”, then a quote from a 1980s article [1] would have direct resonance today: “It is important for hospital and residency program administrators to realize that concerns about personal risk may continue to prevail among health workers caring for AIDS patients, and that these concerns not only have a significant impact upon their personal and professional lives, but may detract from the medical care available to AIDS patients at a time when increasing medical resources will be required.”

The HCWs in our study were particularly concerned about potentially exposing their families and friends to EVD (90%), and this was out of proportion to their degree of concern for personal risk (16.8%). In fact, concern about exposing family and friends had the highest odds ratio (11.1) among the predictors of unwillingness to care for patients with Ebola. Female HCWs, who may be more likely to be primary care providers for their family, were also more likely to be unwilling to care for patients with Ebola. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that pregnant HCWs not care for patients with EVD, there are no recommendations for female HCW who may be breast feeding or caring for infants or young children at home. Healthcare workers may feel themselves torn between their ethical beliefs and duty towards their patients on one hand and moral obligations and responsibility to their family on the other. Therefore, it is in the public interest to find the means to make it possible for HCWs to care for patients without abandoning their responsibility to their families, perhaps by providing workers with (1) child care assistance and (2) temporary living quarters to reduce the risk of disease transmission to family members as well as insurance to protect them and their families should they become ill.

Our study has limitations. The survey was conducted in two hospitals in New York City, and our findings may not be applicable to American HCWs in general. However, to our knowledge, this was the first study focused on Ebola perspectives of HCW after documented transmission of Ebola within the United States. Although we did not find any variables that independently predicted beliefs about whether it is ethical to refuse to care for patients with Ebola, we did not collect information on all potentially important predictors, including factors such as religious beliefs and the psychological profile of the participants. Although the study on HIV by Link et al [1] is similar to our study on Ebola in many respects, there are some important differences. Our study included a range of HCWs, whereas the study on HIV included only physicians. Our decision to include nonphysician HCWs was based on the fact that both HCWs who acquired Ebola within the United States were nurses who cared for the first Ebola patient in Dallas. In addition, the pre-HAART HIV/AIDS era impacted the United States to a much greater degree than Ebola in terms of the number of patients seeking treatment and the number of facilities offering treatment. Our study also has several strengths; apart from the fact that we focused on a unique and relevant public health concern, we recruited HCW from various departments practicing in varied settings. We also recruited HCWs representative of the different components of the healthcare workforce including attending physicians, resident physicians, and nurses.

CONCLUSIONS

In sum, we have found that the response of HCWs to Ebola in the 21st century is similar to that of HCWs in the 1980s to HIV/AIDS. The attitude of HCW towards HIV/AIDS has evolved in the last 3 decades, and a similar evolution may take place with EVD. Healthcare workers' willingness to care for patients with Ebola did not precisely mirror their beliefs regarding whether it would be ethical to refuse to care for those patients, although they were linked. Healthcare workers seem to be balancing their ethical beliefs about patient care with their beliefs about the risks entailed in rendering that care and consequent risks to their families.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was supported by a research grant from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH AIU0131834; to H. M.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Link RN, Feingold AR, Charap MH et al. . Concerns of medical and pediatric house officers about acquiring AIDS from their patients. Am J Public Health 1988; 78:455–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner M. ‘A plague like no other’: Americans panic over first U.S.-diagnosed Ebola patient. Daily News. Available at: http://www.nydailynews.com/life-style/health/americans-panic-u-s-diagnosed-ebola-patient-article-1.1959147 Accessed 5 June 2015.

- 3.Petri A. Ebola? Here? Panic! Panic more! The Washington Post, October 2, 2014 Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/compost/wp/2014/10/02/ebola-here-panic-panic-more/ Accessed 5 June 2015.

- 4.Liebelson D, Stein S. Ebola panic hits schools, businesses, airlines across U.S. The Huffington Post, October 21, 2014 Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/10/21/ebola-panic-america_n_6021136.html Accessed 5 June 2015.

- 5.Yan H. American nurse with protective gear gets Ebola - how could this happen? CNN, October 14, 2014 Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/13/health/ebola-nurse-how-could-this-happen/index.html Accessed 5 June 2015.

- 6.Texas Nurse Says Hospital Should Be ‘Ashamed’ of Ebola Response. ABC News, October 16, 2014 Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Health/texas-nurse-hospital-ashamed-ebola-response/story?id=26255005 Accessed 5 June 2015.

- 7.Highsmith HY, Cruz AT, Guffey D et al. . Ebola knowledge and attitudes among pediatric providers before the first diagnosed case in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34:901–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schram J, Celona L. Bellevue staffers call in “sick” after Ebola arrives. New York Post, October 25, 2014 Available at: http://nypost.com/2014/10/25/many-bellevue-staffers-take-sick-day-in-ebola-panic/ Accessed 4 June 2015.

- 9.Fox News. Hospital staffers reportedly take sick day rather than treat New York's first Ebola patient. Available at: http://www.foxnews.com/health/2014/10/25/hospital-staffers-reportedly-take-sick-day-rather-than-treat-new-yorks-first/. Accessed 4 June 2015.

- 10.Venkat A, Wolf L, Geiderman JM et al. . Ethical issues in the response to Ebola virus disease in US emergency departments: a position paper of the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Emergency Nurses Association and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Nurs 2015; 41:e5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Medical Association. Opinion 9.067 - Physician Obligation in Disaster Preparedness and Response. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion9067.page Accessed 23 June 2015.

- 12.Rowell J. Montana nurses concerned about Ebola. Great Falls Tribune, October 15, 2014 Available at: http://www.greatfallstribune.com/story/news/local/2014/10/15/montana-nurses-concerned-ebola/17340921/ Accessed 4 June 2015.