To the Editor: The human four and a half LIM domain 1 (FHL1) gene, located on Xq26.3, encodes for a protein with only LIM domains. LIM domains, named after their initial discovery in the proteins Lin11, Isl-1, and Mec-3, are cysteine-rich protein motifs composed of two contiguous zinc finger domains separated by a two-amino acid residue hydrophobic linker. At least three splice patterns have been identified, resulting in three protein isoforms: FHL1A with four and a half LIM repeats, FHL1B with three and a half repeats, and FHL1C with two and a half repeats. All isoforms are highly expressed in skeletal muscle and heart, where they are reported to play multiple roles in cell growth and function. Mutations of FHL1 gene could cause a series of diseases characterized by cardiac defects and/or skeletal muscle abnormalities.[1] Recently, the FHL1 gene has been identified as one of the causative genes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).[2] HCM is characterized by asymmetric left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. The phenotype ranged from asymptomatic to dyspnea, heart failure, syncope, and sudden death. Here we report a Chinese male with HCM and mild skeletal muscle hypertrophy who was identified with a novel FHL1 mutation.

A 19-year-old male was presented for intermittent weakness and exertional dyspnea during the past year. No chest pain, fatigue, syncope, or paralysis was reported. His parents were completely asymptomatic, with normal results of cardiovascular and neurological examinations. Both of his maternal grandmother's brothers had unexplained cardiac diseases in their 50s and died 5 years later. None of his other family relatives had cardiac or skeletal muscle diseases. On general examination, the patient was normotensive. Chest and heart auscultations were normal. Jugular vein was normal, and there was no peripheral edema. Neurologic examination revealed an athletic habitus with hypertrophy of all limb muscles, and a short neck. Other neurologic examinations were unremarkable. The 6-min walk test was within normal range.

Laboratory examination revealed increased serum creatine kinase (741 U/L, normal 18–198 U/L) with normal CK-MB and cTnI. Screening for auto-antibodies was negative. Electrocardiogram demonstrated sinus rhythm and tittered right axis. Echocardiography showed asymmetrical LV hypertrophy with a maximal wall thickness of 18 mm at mid-septum. The LV outflow was normal. Left atrium was enlarged to 36 mm. Pulmonary systolic pressure was slightly raised to 46 mmHg. Magnetic resonance imaging of the heart demonstrated enlarged LV and right ventricle in a spiral pattern with a maximal wall thickness of 18.3 mm at mid-septum. LV ejection fraction was 64.4%. First pass and delayed scanning after gadolinium infusion was normal. Pulmonary function was normal. Electromyography test did not detect any muscular or neurologic abnormality. Biopsy of the thigh muscle demonstrated general moderate hypertrophy of muscular fibers with scattered muscle fiber atrophy, no necrosis or regeneration was seen. No reducing body (RB) was found.

Genomic DNAs were available from the described patient and his parents. Genetic screening of genes causing hereditary skeletal and cardiomyopathies was performed using targeted next-generation sequencing, and the screened gene panel included SGCD, TCAP, TRIM32, TTN, FKTN, MYOT, LMNA, CAV3, EMD, FHL1, LAMA2, ITGA7, SEPN1, ACTA1, DES, CRYAB, LDB3, BAG3, STA, DMD, MYH7, and LAMP2. These results revealed that the young male patient was hemizygous for the nonsense mutation c.542G>A in exon 6 of the FHL1 gene. Other genes were normal in this patient. His mother was heterozygous at this location, while his father was normal. Confirmation study with 50 normal females and 100 normal males revealed no mutation at the locus.

DISCUSSION

The clinical presentation of the reported patient was characterized by clinical HCM and mild skeletal muscle abnormalities. Our patient was similar to the young male patient described by Malfatti et al.,[3] who was presented with HCM and muscle hypertrophy, and was identified with FHL1 mutation.

FHL1 mutation could cause a series of diseases. According to the presentence of a special RB at histological examination, these diseases could be divided into two groups: The RB subgroup, including human RB myopathy, X-linked dominant scapuloperoneal myopathy, and rigid spine syndrome; and the non-RB subgroup, including X-linked myopathy with postural muscle atrophy and generalized hypertrophy and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy 6.[1] Recently, a cardiac phenotype has been observed, including arrhythmias, HCM, dilated cardiomyopathy, and an apical- or mid-ventricular cardiomyopathy phenotype, with none-to-mild skeletal muscle disease.[2] Given the heterogeneity with regard to the severity of muscle involvement and disease progression, the clinical phenotype of this patient could be explained by FHL1 mutation.

The mutation, c.542G>A, locates in exon 6 and is a novel nonsense mutation. Less than 30 different FHL1 mutations have been reported so far. Multiple genotype-phenotype studies indicate that the type of mutations and their locations seem to be crucial. Mutations in the proximal exons, encoding the second LIM domains, produce aggregates of mutant FHL1 proteins in the RB subgroup; while mutations in the distal exons (exon 6–8), affecting the third or fourth LIM domains, are mainly found in the non-RB subgroups.[1] The function of the third LIM domain has not been elucidated, some speculated that this domain may interact with nuclear envelope.[4]

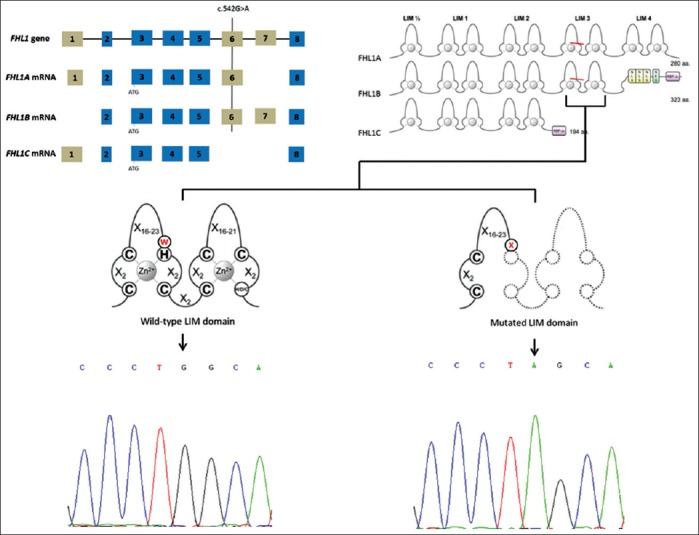

According to the translational patterns, the mutation is predicted to result in a premature stop codon, p. Trp181Ter (p.181W>X), in the third LIM domain, affecting isoforms FHL1A and B [Figure 1], resulting in a truncated protein which was degraded.[2] Studies with transgenic mice showed that FHL1A, localized in the cytoplasm, is an important component of the stress-sensor complex at the sarcomeric I-band in cardiomyocytes. FHL1B and FHL1C isoforms shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, interrupting the normal cardiomyocyte developmental processes.[5] Reduced, instead of accumulation of mutated protein, and preservation of FHL1C might partially explain the milder phenotype of the HCM predominant patients.[2]

Figure 1.

Gene, mRNA, and protein sequence of four and a half LIM domain 1 isoforms. The c.542G>A locates on exon 6, the resultant p.Trp181Ter nonsense mutation results in premature truncation of the third LIM domain. FHL1A and FHL1B isoforms possess this domain and are probably affected by the mutation, while isoform FHL1C are preserved. The last panel showed the wild-type sequence from a normal person and the mutated sequence of the presenting patient.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first Chinese case of FHL1 mutation associated HCM, and the c.542G>A (p.181W>X) is a novel nonsense mutation. FHL1 mutation should be considered in patients with HCM, especially those accompanied with skeletal muscle disease. Further pathogenic studies are needed to investigate the causative role of this novel mutation in the pathogenesis of hypertrophy and mild skeletal muscle involvement.

Footnotes

Edited by: Jian Gao and Ya-Lin Bao

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cowling BS, Cottle DL, Wilding BR, D'Arcy CE, Mitchell CA, McGrath MJ. Four and a half LIM protein 1 gene mutations cause four distinct human myopathies: A comprehensive review of the clinical, histological and pathological features. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011;21:237–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrich FW, Wilding BR, Reischmann S, Crocini C, Lang P, Charron P, et al. Evidence for FHL1 as a novel disease gene for isolated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3237–54. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfatti E, Olivé M, Taratuto AL, Richard P, Brochier G, Bitoun M, et al. Skeletal muscle biopsy analysis in reducing body myopathy and other FHL1-related disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:833–45. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a23506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knoblauch H, Geier C, Adams S, Budde B, Rudolph A, Zacharias U, et al. Contractures and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a novel FHL1 mutation. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:136–40. doi: 10.1002/ana.21839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheikh F, Raskin A, Chu PH, Lange S, Domenighetti AA, Zheng M, et al. An FHL1-containing complex within the cardiomyocyte sarcomere mediates hypertrophic biomechanical stress responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3870–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI34472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]