Abstract

Objective

To identify characteristics associated with past malpractice lawsuits and how malpractice concerns may affect interpretive practices.

Methods

We surveyed 207 of 301 (68.8%) eligible dermatopathologists who interpret melanocytic skin lesions in ten states. The survey assessed dermatopathologists’ demographic and clinical practice characteristics, perceptions of how medical malpractice concerns could influence their interpretive practices, and past malpractice lawsuits.

Results

Thirty-three percent of dermatopathologists reported past malpractice experiences. Factors associated with being sued included older age (57 years vs. 48, p<0.001), lack of board certification or fellowship training in dermatopathology (76.5% vs. 53.2%, p=0.001), and greater number of years interpreting melanocytic lesions (>20 years: 52.9% vs. 20.1%, p<0.001). Sixty four percent of participants reported being moderately or extremely confident in their melanocytic interpretations. Although most dermatopathologists believed that malpractice concerns increased their likelihood of ordering specialized pathology tests, obtaining recuts, and seeking a second opinion, none of these practices were associated with past malpractice. Most dermatopathologists reported concerns about potential harms to patients that may result from their assessments of melanocytic lesions.

Conclusions

Most dermatopathologists reported apprehension about how malpractice affects their clinical practice and are concerned about patient safety irrespective of whether they had actually experienced a medical malpractice suit.

Introduction

Malpractice claims related to the misdiagnosis of melanoma are not uncommon (1–5). One study reported that among claims submitted to a large national malpractice carrier, 8.6% were claims against pathologists and 14.2% were claims against dermatologists related to skin cancer and/or melanoma (2). Two additional studies found that a false negative diagnosis of melanoma was the most common cause of a malpractice pathology-related claim, representing 13% of 335 pathology-related claims (3, 4). Another study found that melanoma was the second most common source of malpractice litigation in the U.S (5). Historically, dermatologists have been at increased risk of medical malpractice compared to pathologists, but this appears to be changing, as patients are better informed about the role pathologists play in their care (6).

A paper by Troxel (2), published in 2003, reported recommendations from a consensus meeting on melanoma risk management. These recommendations derived from the consensus panel included but were not limited to: 1) ordering complete rather than partial excisional biopsies for all melanocytic lesions versus partial biopsies, insisting on good histologic sections (e.g., not doing frozen sections on melanocytic lesions), requesting re-excision of “problem” lesions, and commenting on margins, even for benign lesions; 2) obtaining consultation from an expert dermatopathologist; and 3) ordering a panel of immunohistochemical stains to confirm or rule out the possibility of a melanoma.

The Troxel report was published more than 10 years ago, yet we found no literature reporting on the use of the above recommendations. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact that personal experience with malpractice may have on clinical practices related to interpretation of melanocytic skin lesions and determine if dermatopathologists believe that additional testing or other activities, such as those recommended by the consensus panel, will protect them from future lawsuits (7). Understanding these issues could identify reasons for excessive use of services in patient care and variability in interpretations.

METHODS

Study Participants

We surveyed 207 dermatopathologists regarding their practice and demographic characteristics, prior experience with malpractice, and perceptions about how malpractice concerns and experiences influence dermatopathology practice. Study procedures included identifying, consenting and enrolling dermatopathologists in 10 states, and completing an online survey. All procedures were HIPAA compliant, and Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Rhode Island Hospital, and Dartmouth College all granted approval for study activities.

We identified potential participants from community and university laboratories/practices in several geographically diverse states (CA, CT, HI, IA, KY, LA, NJ, NM, UT, WA). These states where chosen because they were likely to have significant dermatopathology practice due to sun exposure. Funding limited our ability to expand the study across the entire nation. A list of 864 potential participants was generated using Internet searches and the registries of professional organizations, which was updated through telephone calls to pathology laboratories/practices. Eligibility requirements included receiving pathology or dermatology training (e.g., residency with or without fellowship in anatomic/clinical pathology, dermatology or dermatopathology), interpreted melanocytic skin biopsies within the previous year, and plans to continue interpreting cutaneous melanocytic lesions for the next two years. Our use of the term dermatopathologists in this paper does not indicate all were board certified in dermatopathology. Rather it indicates their practice included interpreting cutaneous lesions. Dermatopathologists were enrolled using e-mail (two attempts), regular mail (one attempt), and telephone follow-up (two attempts) between July 2013 and August 2014. Informed consent was completed online, after which dermatopathologists were asked to complete an online survey.

Survey Design, Development and Data Collection

Survey content was developed in consultation with a panel of dermatopathologists and dermatologists (authors RB, DE, MP, MW). After initial development, the survey underwent iterative pilot testing with revisions using cognitive interviewing techniques (8) with pathologists (n=8) similar to study participants, but who resided and worked in a state not included in the study. The final survey collected information from participating dermatopathologists on demographic and professional information (age, sex, training, and clinical practice setting); opinions about clinical practices regarding cutaneous melanocytic lesions, including perceived level of experience and confidence; and perceived clinical variables that might impact diagnosis, such as the frequency of requests for additional tests (e.g., fluorescence in situ hybridization/ comparative genomic hybridization molecular analysis and immunohistochemistry), use of 2nd opinions, treatment recommendations and reporting, use of digitized whole slide imaging, and concerns about medical malpractice and how these might influence their practice.

Of the 864 initial potential participants, the locations of 450 were verified. Of these, 301 were eligible for participation, and 207 (68.8%) enrolled in the study. Another 39 declined, but did not offer eligibility status, and 110 were reportedly ineligible because they relocated to a non-participating state (n=3), retired or anticipated retirement (n=22), were not actively interpreting melanocytic skin lesions (n=40), or provided no reason (n=44). One participant died following the recruitment period.

Statistical Analyses

Survey responses were analyzed using frequencies, percentages, and means both for the overall sample, and when stratified by prior malpractice experience. Continuous variable values are reported as means and standard deviations. Chi-square and one-way ANOVA tests were used to assess differences in demographic, training, and practice characteristics between dermatopathologists who experienced prior lawsuits and those who reported never being sued. All statistical analyses were performed using a commercially available statistical package (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Tests of statistical significance were based on two-sided probability (p<0.05).

We examined the association between prior experience with malpractice and responses to participants’ perceptions about how malpractice influences their interpretations of melanocytic lesions. Outcomes were originally reported on a 6-point Likert-type scale and scored on a continuum from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Scale responses were dichotomized and used as dependent variables in multivariable logistic regression models. Dichotomized responses were defined as agree when responses included ‘slightly agree’, ‘agree’, and ‘strongly agree’ and disagree when responses included ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, and ‘slightly disagree’. Covariates used in the adjusted models were selected from significant differences in the descriptive characteristics or from investigators’ knowledge of common covariates. Results from the unadjusted binary logistic regression models were adjusted sequentially using blocks of covariates, controlling first for demographics (gender, age), and then cumulatively for training and volume experience (considered an expert in the assessment of melanocytic lesions and usual caseload that represents these lesions).

Results

Pathologist Characteristics and Past Malpractice Experience

The majority of participants were male (59.4%), had no affiliations with academic medical centers (71.5%), and were neither board certified nor fellowship trained in dermatopathology (60.9%) (Table 1). Sixty-seven percent of the 207 dermatopathologists reported no previous malpractices claims initiated or filed against them, while 33% reported one or more. Physician characteristics associated with having a malpractice claim included older age (mean age of 57 years vs. 48, p<0.001), and lack of board certification or fellowship training in dermatopathology (76.5% vs. 53.2%, p=0.001).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics Associated with Past Malpracticea Experience*

| Participant Characteristics | Total n (col %) | Never been sued n (col %) | Sued n (col %) | p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 207 (100.0) | 139 (67.1) | 68 (32.9) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 51 (10.2) | 48 (9.1) | 57 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.092 | |||

| Female | 84 (40.6) | 62 (44.6) | 22 (32.4) | |

| Male | 123 (59.4) | 77 (55.4) | 46 (67.6) | |

| Affiliations/Training/Board Certification | ||||

| Affiliation with academic medical center | 0.26 | |||

| No | 148 (71.5) | 95 (68.3) | 53 (77.9) | |

| Yes, adjunct/affiliated | 38 (18.4) | 27 (19.4) | 11 (16.2) | |

| Yes, primary appointment | 21 (10.1) | 17 (12.2) | 4 (5.9) | |

| Residency | 0.84 | |||

| Anatomic/Clinical Pathology | 186 (89.9) | 123 (88.5) | 63 (92.6) | |

| Dermatology | 17 (8.2) | 13 (9.4) | 4 (5.9) | |

| Both Dermatology & Anatomic/ Clinical Pathology | 4 (1.9) | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Residency | 0.35 | |||

| Anatomic/Clinical Pathology | 186 (89.9) | 123 (88.5) | 63 (92.6) | |

| Dermatology c | 21 (10.1) | 16 (11.5) | 5 (7.4) | |

| Board Certification/Fellowship Training | 0.001 | |||

| Board certified or fellowship trained in Dermatopathology d | 81 (39.1) | 65 (46.8) | 16 (23.5) | |

| Other board certification or fellowship training | 126 (60.9) | 74 (53.2) | 52 (76.5) | |

Note: frequencies and percentages except where continuous data are presented; percentages may not total 100 due to rounding

Malpractice experience, a check all that apply variable, is categorized to two groups: 1) never been sued and l2) aw suits related to melanocytic skin lesions (MSL) or related to other pathology and/or medical cases

Sued vs. not sued, for dichotomous variables: p-value for chi-square test (Fisher's exact when cells have expected counts of less than 5), for comparison of means: p-value for t-test.

Includes 4 participants completing residency in both Dermatology and Anatomic/Clinical Pathology.

This category consists of physicians with single or multiple fellowships that include dermatopathology. Also includes physicians with single or multiple board certifications that include dermatopathology.

Clinical Practice Characteristics and Past Malpractice Experience

Clinical practice characteristics associated with having a malpractice claim included greater number of years interpreting melanocytic lesions (>20 years 52.9% vs. 20.1%, p<0.001); lower representation of melanocytic lesions in their caseloads (<10% melanocytic lesions 54.4% versus 38.1%, p=0.02); higher frequency of providing second opinions on melanocytic lesions (>25 times per month 19.4% vs. 7.4%; p=0.03); and being considered an expert in assessment of melanocytic lesions by their colleagues (47.5% vs. 32.4%; p=0.04) (Table 2). Forty-four percent of participants reported interpreting five or fewer cases of melanoma per month and less than 50 benign melanocytic lesions interpreted per month (47.9%). Melanoma caseload was not associated with a malpractice lawsuit (Table 2). Approximately 70% of dermatopathologists reported that interpreting melanocytic skin lesions makes them more nervous than other types of pathology, and nearly 75% reported being concerned about patient safety and potential harm to patients that may result from their assessments of melanocytic lesions, though neither of these variables was associated with a prior lawsuit.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics Associated with Malpractice Experience a (n=207)

| Clinical Practice Characteristics | Total n (col %) | Never been sued n (col %) | Sued n (col %) | p-value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 207 (100.0) | 139 (67.1) | 68 (32.9) | ||

| Years interpreting melanocytic skin lesions c | <0.001 | |||

| < 5 | 33 (15.9) | 30 (21.6) | 3 (4.4) | |

| 5–9 | 47 (22.7) | 38 (27.3) | 9 (13.2) | |

| 10–19 | 63 (30.4) | 43 (30.9) | 20 (29.4) | |

| ≥ 20 | 64 (30.9) | 28 (20.1) | 36 (52.9) | |

| Percent of caseload interpreting melanocytic skin lesions (%) | 0.017 | |||

| < 10 | 90 (43.5) | 53 (38.1) | 37 (54.4) | |

| 10–24 | 79 (38.2) | 55 (39.6) | 24 (35.3) | |

| 25–49 | 29 (14.0) | 26 (18.7) | 3 (4.4) | |

| ≥ 50 | 9 (4.3) | 5 (3.6) | 4 (5.9) | |

| Average number of melanoma cases (melanoma in situ and invasive melanoma) interpreted per month | 0.60 | |||

| ≤5 | 91 (44.0) | 58 (41.7) | 33 (48.5) | |

| 5–9 | 53 (25.6) | 36 (25.9) | 17 (25.0) | |

| ≥ 10 | 63 (30.4) | 45 (32.4) | 18 (26.5) | |

| Average number of benign melanocytic skin lesions interpreted per month | 0.15 | |||

| < 25 | 62 (30.0) | 38 (27.3) | 24 (35.3) | |

| 25–49 | 37 (17.9) | 23 (16.5) | 14 (20.6) | |

| 50–149 | 54 (26.1) | 43 (30.9) | 11 (16.2) | |

| ≥ 150 | 54 (26.1) | 35 (25.2) | 19 (27.9) | |

| In a typical month, how many melanocytic skin lesions do you receive from pathologist colleagues seeking a second opinion? | 0.033 | |||

| None | 52 (25.1) | 37 (26.6) | 15 (22.1) | |

| 1–9 | 60 (29.0) | 33 (23.7) | 27 (39.7) | |

| 10–24 | 63 (30.4) | 42 (30.2) | 21 (30.9) | |

| ≥25 | 32 (15.5) | 27 (19.4) | 5 (7.4) | |

| In a typical month, how many melanocytic skin lesions do you request a second opinion? | 0.99 | |||

| None | 22 (10.6) | 14 (10.1) | 8 (11.8) | |

| 1 | 54 (26.1) | 37 (26.6) | 17 (25.0) | |

| 2–4 | 41 (19.8) | 28 (20.1) | 13 (19.1) | |

| 5–9 | 40 (19.3) | 26 (18.7) | 14 (20.6) | |

| ≥10 | 50 (24.2) | 34 (24.5) | 16 (23.5) | |

| For what percentage of MSL is your final assessment that the diagnosis is borderline or uncertain? | 0.93 | |||

| None | 21 (10.1) | 15 (10.8) | 6 (8.8) | |

| 1 | 52 (25.1) | 33 (23.7) | 19 (27.9) | |

| 2–4 | 41 (19.8) | 28 (20.1) | 13 (19.1) | |

| 5–9 | 58 (28.0) | 38 (27.3) | 20 (29.4) | |

| ≥10 | 35 (16.9) | 25 (18.0) | 10 (14.7) | |

| Considered an expert in melanocytic skin lesions by colleagues | 0.039 | |||

| No | 119 (57.5) | 73 (52.5) | 46 (67.6) | |

| Yes | 88 (42.5) | 66 (47.5) | 22 (32.4) | |

| Perceptions about Interpretation d | ||||

| What are your thoughts on interpreting melanocytic skin lesions? | ||||

| Interpreting melanocytic skin lesions makes me more nervous than other types of pathology | 0.75 | |||

| Agree | 146 (70.5) | 99 (71.2) | 47 (69.1) | |

| Disagree | 61 (29.5) | 40 (28.8) | 21 (30.9) | |

| I am concerned about patient safety and potential harm to patients that may result from my assessment of melanocytic skin lesions | 0.98 | |||

| Agree | 155 (74.9) | 104 (74.8) | 51 (75.0) | |

| Disagree | 52 (25.1) | 35 (25.2) | 17 (25.0) | |

Note: frequencies and percentages except where continuous data are presented; percentages may not total 100 due to rounding

Malpractice experience, a check all that apply variable, is categorized to two groups: never been sued and law suits related to melanocytic skin lesions (MSL) or related to other pathology and/or medical cases

For comparison of sued vs not sued, categorical data: p-value for chi-square test (Fisher's exact when cells have expected counts of less than 5).

Not including residency/fellowship training

Dichotomized responses for Likert scale responses are defined as ‘slightly agree’, ‘agree’, and ‘strongly agree’ for agree and ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, and ‘slightly disagree’ for disagree.

Enjoyment, Anxiety About Patient Safety, and Confidence and Past Malpractice Experience

The majority of participants reported enjoying interpreting melanocytic lesions (70%), although most (71%) also reported interpreting melanocytic lesions make them more nervous than other types of pathology. The majority of participants also reported being moderately or extremely confident (64%) in their melanocytic interpretations. None of these perceptions of enjoyment, anxiety, or confidence in interpretations was associated with having been sued, and we found no association between confidence and academic affiliation (data not shown).

Perceived Influence of Medical Malpractice Concerns on Interpretative Behavior

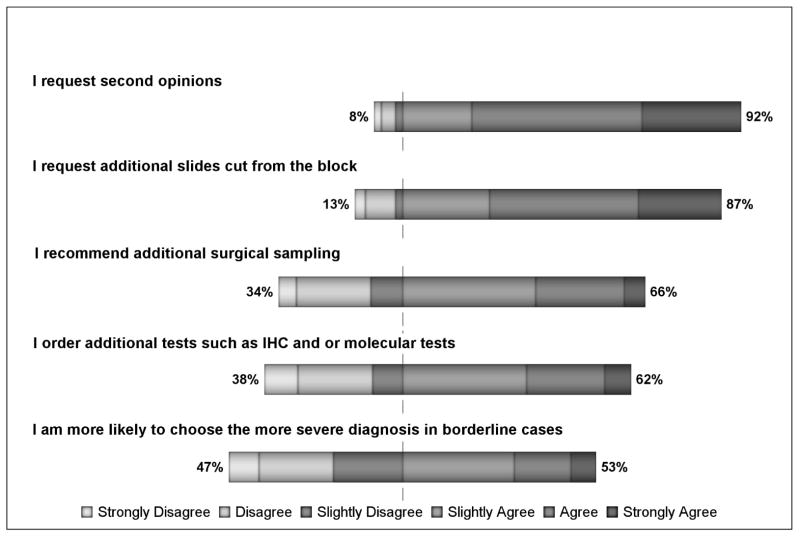

Figure 1 outlines participating dermatopathologists’ perceptions of how medical malpractice influences their interpretative behavior according to whether they report having experienced a malpractice claim. While the majority of participants report requesting second opinions (92%), requesting additional slides be cut from tissue blocks (87%), ordering additional surgical samples be taken from patients (66%) or immunohistochemical tests (62%), and choosing a more severe diagnosis for borderline cases (53%). None of these variables was associated with having a malpractice claim (data not shown). After adjusting for age, sex, training, interpretive volume, and whether colleagues consider them experts, we found no evidence that a past malpractice experience influenced dermatopathologists’ ordering of specialized pathology testing, additional surgical sampling or slides, seeking a second opinion, or rendering a more severe diagnosis for borderline lesions (Table 3).

Figure 1.

This figure shows participants survey responses in terms of level of agreement/disagreement regarding how concerns about medical malpractice may affect their practices.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted likelihood of self-reported practices among pathologists who experienced any malpractice suits (referent group is never have been sued) using binary logistic regression (n=207)

| Physician Practices * | Unadjusted Odds OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted for Demographics† OR (95% CI) | p-value | Additionally adjusted for Training and Volume Experience § OR (95% CI) | p-value | Additionally adjusted for Perceptions about Interpretation¶ OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I order additional tests such as IHC and or molecular tests overall agreement: 129 (62.3%) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.6) | 0.67 | 1.1 (0.6, 2.2) | 0.74 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.3) | 0.66 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.2) | 0.68 |

| I recommend additional surgical sampling overall agreement: 137 (66.2%) | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | 0.76 | 1.5 (0.8, 3.0) | 0.25 | 1.8 (0.9, 3.6) | 0.12 | 1.8 (0.9, 3.6) | 0.12 |

| I request additional slides cut from the block overall agreement: 180 (87%) | 1.0 (0.4, 2.3) | 0.95 | 1.5 (0.6, 3.9) | 0.40 | 1.7 (0.6, 4.4) | 0.30 | 1.7 (0.6, 4.3) | 0.31 |

| I request second opinions overall agreement: 191 (92.3%) | 1.1 (0.4, 3.3) | 0.89 | 1.8 (0.5, 6.0) | 0.37 | 1.8 (0.5, 6.2) | 0.34 | 1.7 (0.5, 6.3) | 0.39 |

| I am more likely to choose the more severe diagnosis in borderline cases overall agreement: 109 (52.7%) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.2) | 0.52 | 1.5 (0.8, 3.0) | 0.18 | 1.6 (0.8, 3.1) | 0.15 | 1.6 (0.8, 3.0) | 0.18 |

Covariates for demographics include: gender, age

Covariates for experience/volume include: number of benign cases (per month) and whether or not peers consider participant an expert

Covariates for perceptions about interpretation include: more nervous about MSL interpretation than other types of pathology

Discussion

Though several studies have reported medico-legal issues associated with interpretation of melanocytic lesions (1–7, 9), this study is the first to examine how dermatopathologists view their clinical practices are influenced by malpractice. We found that older dermatopathologists, and thus in practice longer, were more likely to have been sued compared to younger dermatopathologists. Fellowship training or board certification in dermatopathology was associated with a lower likelihood of being sued, indicating that additional training may reduce the risk of a malpractice experience. We also found that lower representation of melanocytic lesions in their caseload resulted in higher reported malpractice experience, which might be related to a lack of volume or experience interpreting complex melanocytic lesions. Importantly, the majority of dermatopathologists reported having concerns about potential harms to patients suggesting that dermatopathologists fully understand the consequences of diagnostic errors.

Most dermatopathologists in our study reported enjoying interpreting melanocytic lesions as well as being confident in their interpretations, even though most reported that interpreting these lesions makes them more nervous compared to other types of non-melanocytic tissue. Though 64% reported being moderately or extremely confident in their melanocytic interpretations, this means that 36% were less confident. This likely reflects the challenging aspects associated with interpreting these lesions and the consequences of getting them wrong. Perhaps seeing complex skin lesions contributes to enjoyment and the development of confidence over time, even though concerns exist about possible misinterpretations that could have clinical and/or legal significance. We found no perceived interpretive behaviors to be associated with a history of being sued, although clearly dermatopathologists perceive that they request second opinions as well as having additional slides cut from tissue blocks and ordering additional surgical samples and ancillary tests because of concerns about malpractice.

These findings suggest that dermatopathologists are for the most part following recommendations in the Troxel report (2). The full set of recommendations include: 1) improving communication with referring dermatopathologists regarding clinical information (age, sex, site, working diagnosis, new or recurrent lesion, and lesional diameter if a shave or punch biopsy); 2) ordering complete excisional biopsies for all melanocytic lesions versus partial biopsies, insisting on good histologic sections (not doing frozen sections on melanocytic lesions), requesting re-excision of “problem” lesions, and commenting on the presence of nevocytes at margins, even for benign lesions; 3) examining all melanocytic lesions under high power, even if they appear to be typical nevi under low power; 4) looking for mitoses (frequent and deep), cytologic atypia, coalescence of nests, melanin in deep tumor cells, and lymphohistiocytic infiltrates; 5) obtaining consultation from an expert dermatopathologist for Spitz nevus; 6) assessing presence of scars in the dermis of all melanocytic lesions; 7) ordering a panel of immunohistochemical stains for possible undifferentiated carcinoma or a melanoma; and 8) issuing written reports to document verbal consultations, as without a written report, the only record is the clinician’s recollection of the conversation or a handwritten note made in the office record or chart, which may be incomplete or inaccurate.

Our study found that the majority of dermatopathologists ordered additional tests specifically because of their concerns about medical malpractice. However, clinical practices appear not to be affected by having a personal experience with a medical malpractice claim. Dermatopathologists, like other physicians, are likely well aware of malpractice and discuss these experiences among colleagues. Thus, a lawsuit is not needed for dermatopathologists to be aware of and undertake behaviors that might protect them from a suit. Our results indicate that most dermatopathologists have concerns about patient harms associated with their interpretations of melanocytic lesions; thus, they are not just concerned for themselves.

The strengths of this study include that the sample was representative of dermatopathologists who interpret cutaneous lesions in 10 U.S. states and that we conducted a detailed analysis of the data obtained from the survey. Weaknesses include lack of validation and details about the malpractice suits experienced by participating dermatopathologists. Also, this study assessed perceptions of practice rather than actual practices that might be associated with malpractice incidents. Thus, it is not possible to determine from these findings whether these whether actual clinical practice is affected by concerns about medical malpractice.

In conclusion, older dermatopathologists who have been in practice longer, and those with training and board certification in an area other than dermatopathology were more likely to be sued than younger dermatopathologists. The majority of dermatopathologists report that concerns about malpractice affect their interpretive behavior, especially for requesting second opinions and requesting additional slides be cut from the tissue block.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA151306). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None Declared

IRB Status: Approved

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.High WA. Malpractice in dermatopathology – Principles, risk, mitigation and opportunities for improved care for histologic diagnoses of melanoma and pigmented lesions. Clinics in Lab Med. 2008;28(2):261–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Troxel DB. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Am J surg Pathol. 2003;27:1278–1283. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troxel DB. An insurer’s perspective on error and loss in pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1234–1236. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1234-AIPOEA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troxel DB. Medicolegal aspects of error in pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:617–619. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-617-MAOEIP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troxel DB, Sabella JD. Problem areas in pathology practice. Uncovered by a review of malpractice claims. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:821–831. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199408000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein JI. Pathologists and the judicial process: how to avoid it. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:527–537. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrier ER, Reschovsky JD, Katz DA, Mello MM. High Physician Concern About Malpractice Risk Predicts More Aggressive Diagnostic Testing In Office-Based Practice. Health Affairs. 2013;32(8):1383–1391. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsch A, High WA. Medicolegal issues with regard to melanoma and pigmented lesions in dermatopathology. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:593–615. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]