Abstract

The progressive decline of lung function with aging is associated with changes in lung structure at all levels, from conducting airways to acinar airways (alveolar ducts and sacs). While information on conducting airways is becoming available from computed tomography, in vivo information on the acinar airways is not conventionally available, even though acini occupy 95% of lung volume and serve as major gas exchange units of the lung. The objectives of this study are to measure morphometric parameters of lung acinar airways in living adult humans over a broad range of ages by using an innovative MRI-based technique, in vivo lung morphometry with hyperpolarized 3He gas, and to determine the influence of age-related differences in acinar airway morphometry on lung function. Pulmonary function tests and MRI with hyperpolarized 3He gas were performed on 24 healthy nonsmokers aged 19-71 years. The most significant age-related difference across this population was a 27% loss of alveolar depth, h, leading to a 46% increased acinar airway lumen radius, hence, decreased resistance to acinar air transport. Importantly, the data show a negative correlation between h and the pulmonary function measures forced expiratory volume in 1 s and forced vital capacity. In vivo lung morphometry provides unique information on age-related changes in lung microstructure and their influence on lung function. We hypothesize that the observed reduction of alveolar depth in subjects with advanced aging represents a remodeling process that might be a compensatory mechanism, without which the pulmonary functional decline due to other biological factors with advancing age would be significantly larger.

Keywords: in vivo lung morphometry, MRI, hyperpolarized gas, alveolar ducts and sacs, airway remodeling

lung function declines with aging in healthy individuals (21, 29), and this process accelerates in diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (11, 19, 26). However, little information exists on the structural changes responsible for this decline (25). While data on conducting airways is becoming available from in vivo computed tomography imaging (11, 19, 26), our knowledge of alterations at the level of acinar airways [alveolar ducts and sacs which occupy about 95% of lung volume (49)] is very limited because until recently no tools were available for in vivo evaluation of these microscopic distal branches of the airway tree. In the past, such measurements relied primarily on invasive histology (8, 15, 20, 22, 27, 40, 41, 46, 49).

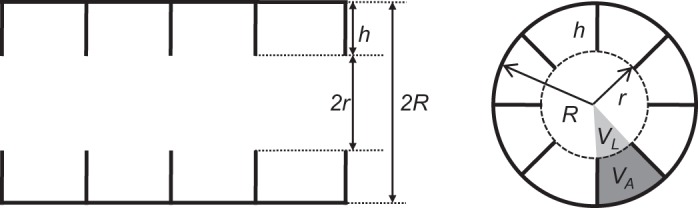

The recently introduced in vivo lung morphometry technique with hyperpolarized 3He gas MRI (53, 54) is safe (24), validated (54), reproducible (36), and highly sensitive for the noninvasive measurement of acinar airways and alveoli microstructural parameters (37, 54). Helium-3 gas lung morphometry describes the acinar airways in the framework established by Weibel and colleagues (15, 40) as cylindrical passages lined with alveolar sleeves, which are characterized by the alveolar sleeve depth (h), acinar airway radius (R), and acinar airway lumen radius (r = R − h), as shown in Fig. 1. From these parameters numerous other morphologic measurements can be calculated (54). This technique has previously been used to measure changes in acinar airway geometry in human lungs related to pneumonectomy (6), emphysema (37, 54), and inspiratory volume (16). It has also been used to study small animal lungs (33, 47) and was recently extended for use with hyperpolarized 129Xe gas (34, 35, 44).

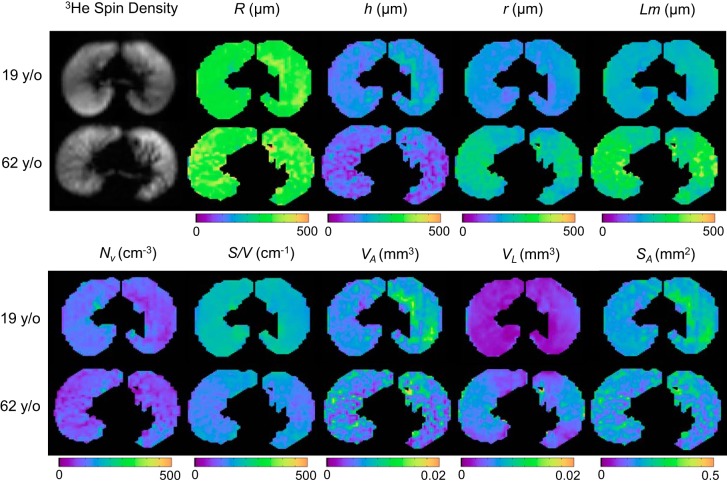

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal (left) and cross-sectional (right) views of the model of an acinar airway illustrating the main model parameters (h, alveolar depth; and R, acinar airway radius) as well as three of the derived parameters (r, acinar airway lumen radius; VL, acinar airway lumen volume; and VA, alveolar volume).

Previous measurements of the 3He apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in lungs of adults (10, 48) and children (2, 31) found that older subjects had increased ADC values, suggesting a reduction of restrictions to gas diffusion within the acinar airways. However, characterizing the differences in acinar structure is beyond the capabilities of the ADC method because the relationship between ADC and acinar geometric parameters is ambiguous (see Fig. 14 in Ref. 53). To the contrary, in vivo lung morphometry with hyperpolarized 3He MRI used in this study provides direct information on the type and extent of acinar remodeling.

Here we use 3He lung morphometry to noninvasively detect age-dependent differences in acinar microstructure in healthy human subjects and correlate acinar microstructural differences with pulmonary function to determine their contribution to age-related changes in lung function. Our results suggest that the observed reduction of alveolar depth in subjects with advanced ages represent a remodeling process that might be a compensatory mechanism, without which the lung functional decline due to other biological factors with advancing age would be significantly larger.

Since structural changes are known to occur in different lung diseases, establishing the age-dependent baseline is also essential for accurate detection and differentiation of pathological changes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

We conducted a cross-sectional cohort study approved by the Washington University institutional review board (ID No. 201103367), and all study participants provided informed consent. Helium-3 gas MRI was conducted under Food and Drug Administration Investigational New Drug 59,269. The study enrolled 24 adult healthy never-smokers able to perform a 6-min walk, testing with maintenance of oxyhemoglobin saturation of at least 95% by pulse oximetry to help rule out previously undiagnosed pulmonary or cardiac disease. The study excluded people that had preexisting pulmonary, cerebrovascular, hematologic, or cardiac disease, or who were ineligible for MRI.

Helium-3 lung morphometry.

Helium-3 gas was hyperpolarized to ∼40% polarization by using a Nycomed Amersham Imaging IGI.9600.He polarizer (GE Healthcare, Durham, NC). Gradient echo diffusion 3He MRI images were acquired on a Siemens 1.5T MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Iselin, NJ) by using a custom 48-cm-diameter rigid 3He transmit and flexible 8-channel phased array receiver coil set (Stark Contrast MRI Coils Research, Erlangen, Germany) with 7 × 7 mm2 resolution over three 30-mm axial slices (flip angle of 5.5°, TR/TE = 13/8.3 ms, b = 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 s/cm2, gradient pair = 1.8 ms duration per lobe, 0.3 ms rise/fall times, no gap between lobes) (43, 52). The flip angle for helium imaging was calculated from the proton calibration voltage following a previously described technique (3). Subjects inhaled 1 liter of a 40/60 mixture of hyperpolarized 3He gas in nitrogen from functional residual capacity (FRC) and held their breath for 9 s. During 3He imaging, each subject's ECG and oxygen saturation were monitored for potential adverse effects.

Semiautomated segmentation of each lung was performed by using custom software in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) to remove the contribution from the background signal and large conducting airways. For each image voxel, the data from all channels in the receiver array were jointly analyzed by Bayesian probability theory (4, 5, 38) and a previously developed mathematical model of 3He gas diffusion in lung acinar airways (54). In brief, we measure the diffusion MRI signal of inhaled 3He gas, S(b), at multiple b values (characterizing diffusion gradient strength and timing) and use theoretical relationships

| (1) |

to calculate the apparent axial and transverse diffusion coefficients (DL and DT). These diffusion coefficients depend upon the lung microstructural parameters R (acinar airway radius) and h (alveolar depth) shown in Fig. 1 by means of equations derived in Ref. 54 that we do not show here for brevity. Using the parameters R and h, we then estimate the acinar airway lumen radius (r = R − h), mean chord length (Lm), alveolar density (Nv), surface-to-volume ratio (S/V), surface area per alveolus (SA), acinar airway lumen volume per alveolus (VL), and alveolar volume (VA) (54):

| (2) |

As we have previously shown that lung morphometry measurements vary with lung inflation level (16), we standardized the results to account for differences in the relative inflation level across subjects during the MRI experiment. For each subject, we used the known volume dependence of R and h (16) to adjust these values to a consistent inflation level of FRC (the 1 liter decrease in inflation level produces a 5.7-μm decrease in R and an 11.3-μm increase in h). The other parameters were then calculated from the adjusted values of R and h by using Eq. 2.

Pulmonary testing.

Spirometry was performed according to American Thoracic Society guidelines (30) on the same day as imaging.

Statistical analysis.

Study variables consisted of the directly estimated lung morphometric parameters: alveolar depth (h), acinar airway radius (R); the derived lung morphometric parameters: r = R − h, Lm, Nv, S/V, SA, VL, VA; and spirometry measures: forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC. The morphometry measurements for each participant were characterized by the median and standard deviation across the lung. Multivariate regression followed by ANOVA was conducted with the R software package (39) to determine the contribution of age, race, weight, height, and gender for each parameter value, treating P < 0.05 as significant. The age dependence of each parameter was then determined by univariate linear regression. As there are only two independent lung morphometry parameters (h and R), no correction for multiple comparisons was performed.

Spirometry measurements were modeled as a function of demographics and the selected lung morphometry parameters. Model selection was performed by including all candidate parameters and then by using the Akaike Information Criterion (1) to sequentially eliminate parameters that did not make a significant contribution. The resulting model was then used to determine the linear regression coefficients for that spirometry measurement.

RESULTS

The enrolled subjects are described in Table 1 and had largely unremarkable pulmonary function results [FVC % predicted = 104 ± 11 (range 81–133), FEV1% predicted = 101 ± 10 (range 77–121), FEV1/FVC = 0.80 ± 0.07 (range 61–90)]. All helium inhalations were well tolerated and no adverse events occurred. We observed no ventilation defects (regions of low signal due to the inability of helium gas to penetrate into the acinar ducts) in these healthy subjects that would prohibit quantitation of lung morphometry values.

Table 1.

Demographics and pulmonary function results for all subjects in the study

| Parameter | Mean SD [range] |

|---|---|

| Gender | 11 Female/13 Male |

| Race | 6 African American/18 Caucasian |

| Age, yr | 40 ± 18 [19–71] |

| Weight, kg | 173 ± 26 [121–228] |

| Height, cm | 173 ± 10 [155–193] |

| FEV1, liter | 3.59 ± 0.96 [2.13–5.72] |

| FVC, liter | 4.46 ± 1.09 [2.83–6.83] |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 80 ± 7 [61–90] |

Table 2 shows the mean values and age dependence for the lung morphometry parameters at FRC and the spirometry measurements. The model age dependence was determined from a univariate linear regression of that parameter with respect to age. The regression coefficients are given in Table 2 to allow calculation of expected values of these parameters for any adult age. For all of the lung morphometry parameters except for alveolar volume (VA), the age of the study participant was found to be a significant contributor, but race, weight, height, and gender were not. Figure 2 provides examples of the maps of the lung morphometry parameters for a younger and an older participant and illustrates the increased acinar diameter and decreased alveolar depth and alveolar density associated with older subjects. This figure also demonstrates significantly increased heterogeneity across the lung with aging for most parameters (h, Lm, r, S/V, VA, and VL).

Table 2.

Adult acinar geometric parameters

| Regression Coefficients (P value) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Mean ± SD | α0 | α1 (age dependence) |

| R, μm | 310 ± 20 | 292 ± 8 (<2E-16) | 0.45 ± 0.2 (0.018) |

| h, μm | 140 ± 20 | 177 ± 8 (<2E-16) | −0.87 ± 0.2 (0.00011) |

| Lm, μm | 200 ± 40 | 150 ± 20 (4.7E-9) | 1.4 ± 0.4 (0.00084) |

| Nv, cm−3 | 110 ± 20 | 132 ± 8 (2.4E-13) | −0.46 ± 0.2 (0.028) |

| r, μm | 170 ± 40 | 120 ± 10 (2.5E-8) | 1.3 ± 0.3 (0.00040) |

| S/V, cm−1 | 200 ± 30 | 250 ± 10 (1.4E-15) | −1.1 ± 0.3 (0.00065) |

| VA, mm3 | 6.3E-3 ± 7E-4 | 6.7E-3 ± 4E-4 (3.6E-7) | −1.2E-5 ± 8E-6 (0.16) |

| VL, mm3 | 2.8E-3 ± 1E-3 | 7.1E-4 ± 6E-4 (0.238) | 5.3E-5 ± 1E-5 (0.00077) |

| SA, mm2 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.191 ± 0.006 (<2E-16) | −3.3E-4 ± 1E-4 (0.036) |

| (r/R)2 | 0.34 ± 0.1 | 0.18 ± 0.04 (0.00011) | 3.9E-3 ± 9E-4 (0.00022) |

| FEV1, liter | 3.6 ± 1 | 5.0 ± 0.4 (4.7E-12) | −0.036 ± 0.009 (0.00040) |

| FVC, liter | 4.5 ± 1 | 5.7 ± 0.5 (1.3E-10) | −0.030 ± 0.01 (0.017) |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 80 ± 7 | 90 ± 3 (<2E-16) | −0.25 ± 0.07 (0.0015) |

Values are means ± SD. Parameters calculated from 3He lung morphometry (at functional residual capacity) and spirometry results fitted to a univariate linear model: parameter = α0 + α1 age (age in years). Significant P values are given in bold. R, acinar airway radius; h, alveolar depth; Lm, mean chord length; Nv, alveolar density; r, acinar airway lumen radius; S/V, surface-to-volume ratio; VA, alveolar volume; VL, acinar airway lumen volume; SA, surface area per alveolus; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Fig. 2.

Example of lung morphometry parameter maps from the central slice of a younger and an older healthy participant, illustrating the shifts in parameter values and an increased heterogeneity in older subjects. Lm, mean chord length; Nv, alveolar density; S/V, surface-to-volume ratio; SA, surface area per alveolus.

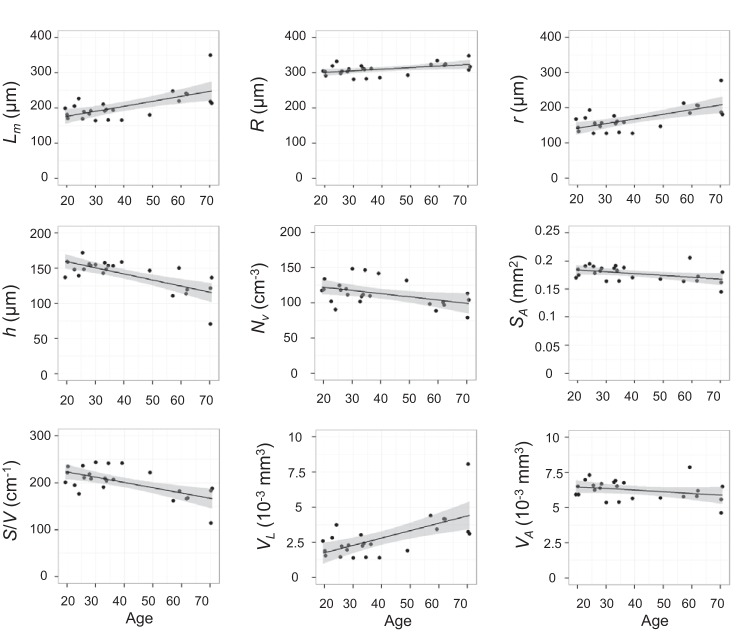

The age dependence of each lung morphometry parameter at FRC is plotted in Fig. 3, along with the linear model and 95% confidence intervals. In older subjects there is a significantly increased acinar airway radius and decreased alveolar depth, density, and surface-to-volume ratio. For example, compared with a 20 year old, a 70 year old would be expected to have a 44 μm (27%) smaller alveolar depth (h) and a 66 μm (46%) larger acinar airway lumen radius (r).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of lung morphometry parameters at functional residual capacity (FRC) with age (all P < 0.05 except VA). The lines are univariate linear fits with 95% confidence intervals (shaded).

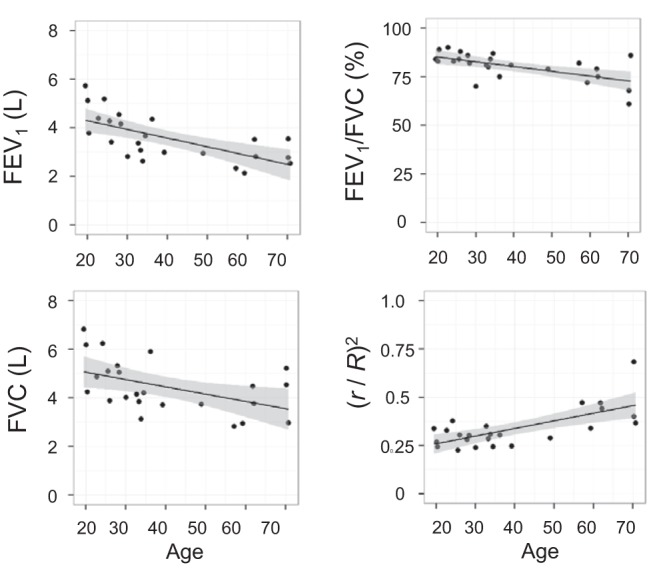

In Fig. 4, the age dependence of the spirometry measurements is plotted along with the linear model and 95% confidence intervals, indicating decreased expiratory flow and capacity with age. FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC are well known to decline with age and for a particular race and gender are typically modeled as functions of age, age2, and height2 (for FEV1 and FVC) or age (for FEV1/FVC) (17). We did not detect race and gender as significant contributors to our data, likely due to the relatively small number of subjects, and therefore further analyses were conducted without including these variables. We augmented the Hankinson healthy prediction models (17), ignoring race and gender, by including h and R (the two basic parameters of our model characterizing lung acinar airways, Fig. 1) as additional parameters and then removing nonsignificant terms in a stepwise fashion based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (1). For our subjects, FEV1 and FVC are functions of age, height2, and h, whereas the FEV1/FVC ratio is a function only of age (Table 3). Both FEV1 and FVC increase with decreasing alveolar depth, h.

Fig. 4.

Correlation of spirometry measurements and (r/R)2 at FRC with age (all P < 0.05). The lines are univariate linear fits with 95% confidence intervals (shaded). FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Table 3.

Linear regression model coefficients for adult spirometry parameters

| Regression Coefficients (P value) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary Function Test | α0 | α1 (age dependence) | α2 (height2 dependence) | α3 (h dependence) | Model P Value |

| FEV1, liter | 2.5 ± 1.4 (0.093) | −0.046 ± 0.007 (1.1E-6) | (1.5 ± 0.2) E-4 (4.53E-6) | −0.012 ± 0.006 (0.042) | 1.6E-8 |

| FVC, liter | 2.4 ± 2.0 (0.23) | −0.044 ± 0.009 (0.00014) | (2.0 ± 0.3) E-4 (8.8E-6) | −0.016 ± 0.008 (0.047) | 7.1E-7 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 2.2 ± 1.9 (<2E-16) | −0.25 ± 0.07 (0.0015) | 1.5E-3 | ||

Values are means ± SD. Lung function parameter = α0 + α1 age + α2 height2 + α3 h (age in years, height in cm, alveolar depth h at FRC in μm). Significant P values are given in bold.

DISCUSSION

Pulmonary function in adults declines with age (13, 17, 22) and manifests as decreased expiratory forced air flow. This decline is usually attributed to a combination of structural and mechanical factors such as airspace enlargement (8, 46) and changes in lung elastic recoil, chest wall, and respiratory muscle function (29). Conventional noninvasive techniques, such as spirometry, report on the function of the entire respiratory system and thus are unable to separate these effects and isolate specific alterations in lung microstructure at the alveolar/acinar level. The measurement of lung microstructure and the assessment of its remodeling by 3He lung morphometry herein provides noninvasive insights into the observed functional decline with age in the healthy human lung.

The most intriguing finding in our study is the negative correlation between the pulmonary function measures of FEV1 and FVC and the depth of the alveolar sleeve h when each subject's age and height2 are factored into the model (Table 3). The significant negative dependence of FEV1 and FVC on h is consistent with the parameter's expected influence on gas transport through the acinar airways. More specifically, gas transport in the acinar airways is primarily attributed to diffusive processes (7). The gas diffusion coefficient along acinar airways was previously modeled by Verbanck and Paiva (45) who determined that it is proportional to the ratio of the acinar airway lumen cross-sectional area πr2 to the total acinar airway cross-sectional area πR2, i.e., (r/R)2. Hence, we can expect that a smaller h (bigger r) decreases the resistance to gas transport and therefore mitigates the decrease of FEV1 with aging. The increase in (r/R)2 with aging also means larger acinar airway lumen size that can delay airway closure upon exhalation. Since airway closure occurs at higher lung volumes with increasing age (51), the increased (r/R)2 also means lessening of the decrease FVC with aging. If we also include this squared ratio as an additional candidate parameter for modeling the dependence of FEV1 or FVC, we find that it replaces h in the final model (based upon the AIC). The regression coefficients and P values for the model including this ratio are given in Table 4, and the age dependence of the squared ratio is shown in Fig. 4. Importantly, the correlation coefficients showing association between both FEV1 and FVC and (r/R)2 are positive, which is consistent with our hypothesis that decreased with aging alveolar depth h in human acinar airways can be considered as an age-related adaptive mechanism.

Table 4.

Linear regression model coefficients for adult spirometry parameters

| Regression Coefficients (P value) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary Function Test | α0 | α1 (age dependence) | α2 (height2 dependence) | α3 [(r/R)2 dependence] | Model P Value |

| FEV1, liter | −0.094 ± 0.7 (0.90) | −0.047 ± 0.006 (2.8E-7) | (1.5 ± 0.2) E-4 (3.2E-6) | 2.9 ± 1.1 (0.016) | 6.9E-9 |

| FVC, liter | −1.1 ± 1.0 (0.30) | −0.044 ± 0.009 (6.6E-5) | (2.0 ± 0.3) E-4 (7.5E-6) | 3.7 ± 1.6 (0.028) | 4.5E-7 |

Values are means ± SD. Lung function parameter = α0 + α1 age + α2 height2 + α3 (r/R)2 (age in years, height in cm). Significant P values are given in bold.

Based on the results in Table 2 and Table 3, we conclude that the reduction in h alone would tend to improve lung function in older subjects, increasing FEV1 and FVC, whereas the FEV1/FVC ratio does not show a statistically significant association with changes in the acinar airways microstructure (Table 3). We hypothesize that the observed differences in acinar airways microstructure between younger and older subjects represent remodeling that might be a compensatory mechanism, without which the functional decline due to mechanical factors with advancing age would be significantly larger. We expect that this compensatory ability is limited by the requirement that there remains sufficient alveolar surface area for efficient gas exchange. This hypothesis is also consistent with the report of Butler et al. (6) who found adult human lung growth after pneumonectomy and a decreased alveolar sleeve depth, h, in the nonresected lung.

Total lung capacity (TLC) increases with height (42); however, it was not certain if an increased alveolar number or an increased alveolar size causes this increase. In the current study, we found that the alveolar density, NV, is not significantly associated with height (nor were any of the other lung morphometry parameters). This suggests that the acinar microstructure is similar for healthy subjects of different heights, which is consistent with the height dependence of TLC being primarily related to differences in the total alveolar number (14).

This study provides in vivo measurements of acinar airway morphometry in normal human lungs over a broad range of ages for the first time. The observed trends in the differences in acinar structure across different ages occurred in the same direction but with smaller magnitude than those associated with the initial changes of emphysema (37) and are consistent with the proposal that COPD is a disease of accelerated lung aging (21). We hypothesize that aging causes a reduction in the alveolar depth and alveolar surface area, due to changes in the structure of the elastin and collagen fiber network that maintains the shape of the acinar airways (22). Concurrently, there is a small increase in the acinar airways radii (R) which, when combined with the reduced alveolar depth, produces a significant increase in the radius of the acinar airways lumen (r). The observed increase of acinar airway radius (R) in older subjects is consistent with the findings of Weibel (50) and the known increase in lung volume with age (9). Though the findings of increased Lm with aging by histology are sometimes interpreted as increases in alveolar size (12), the current results suggest instead that the alveolar volume (VA) is similar in older subjects and that it is the acinar airway lumen that increases in volume (VL). The decreased alveolar S/V is consistent with the reported decline of gas exchange capacity with age (28).

Our in vivo morphometric measurements and their age dependence summarized in Table 2 are comparable to those available from invasive histology measurements. The results we found for the alveolar diameter [L = 0.765 R (54)] are at the high end of published histologic values for the alveolar diameter in nonsmokers that range from 225–260 μm (27, 41, 49). When corrected for differences in inflation volume, Haefeli-Bleuer and Weibel's (15) measurements of acinar dimensions scale to R = 300 μm and r = 140 μm, comparable to our data for young adults in Fig. 4. Gillooly and Lamb (12) measured an average airspace surface-to-volume ratio of 212 cm−1 in 21–23 year olds with an age-related decrease of 0.9 cm−1/yr, and Lang et al. measured S/V of 223 cm−1 at age 22 yr with a decline of 1.36 cm−1/yr (23), both similar to our measurements. Ochs et al. (32) found Nv of 132–177 alveoli/mm3 in 18–41 year olds which is somewhat larger than our average of 110. Verbeken et al. found that Lm increased at 1.4 μm/yr in normal lungs (46), while Colebatch and Ng (8) reported an increase of 1.17 μm/year, both similar to the results in Table 2. Our finding of shallowing of the alveolar sleeve is consistent with prediction of similar effect in emphysema (18) and the concept of COPD as accelerated lung aging (21). Our data are also consistent with previous measurements of the 3He ADC in lungs, which increased with age in adults (10, 48) and children (2, 31).

One limitation of our study is the number of subjects, and we suspect that a larger study would likely detect differences due to race and gender that were not statistically significant in our study. It is possible that such a study would also identify additional significant correlations between the lung morphometry measurements, spirometry results, and participant demographics. However, the results of the current study suggest that such dependencies would be weak compared with those identified herein. Another limitation of our study is a restriction to a specific lung volume (FRC) for 3He MRI. Measurements at several lung volumes, e.g., Ref. 16, would be able to provide more comprehensive information on changes in lung microstructure with aging. The unavoidable cross-sectional nature of this study also restricts us to comparing different cohorts at different ages instead of following subjects over decades to fully determine the effect of aging on acinar microstructure.

In conclusion, this cross-sectional study provides a first noninvasive insight into the differences in acinar airways structure associated with aging in a healthy adult population and their effect on pulmonary function. Helium-3 gas lung morphometry detected significant age-related differences of acinar structure in our healthy participants. Specifically, in older subjects we found decreased alveolar depth, alveolar density, surface area, and surface-to-volume ratio and increased acinar airways lumen radius and volume, mean chord length, and acinar airway radius. Correlations of our morphometry measurements with spirometry data suggest that the decreased alveolar depth could be considered as an age-adaptive mechanism that reduces resistance to gas transport in the distal airways, thus partially compensating for the decline in lung mechanical function. Our results also establish a baseline of age-dependent lung parameters for use in future studies to detect pathologic changes.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01 HL-70037 and R01 HL-091762.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.D.Q. and D.A.Y. conception and design of research; J.D.Q., J.C.W., B.A.L., M.S.C., D.S.G., and D.A.Y. performed experiments; J.D.Q., A.L.S., and D.A.Y. analyzed data; J.D.Q., A.L.S., R.D.Y., M.C., and D.A.Y. interpreted results of experiments; J.D.Q., A.L.S., and D.A.Y. prepared figures; J.D.Q. and D.A.Y. drafted manuscript; J.D.Q., A.L.S., J.C.W., B.A.L., M.S.C., D.S.G., R.D.Y., M.C., and D.A.Y. edited and revised manuscript; J.D.Q., A.L.S., J.C.W., B.A.L., M.S.C., D.S.G., R.D.Y., M.C., and D.A.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Prior Abstract publication: a portion of these results was previously presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Milan, Italy, May 12–16, 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans 19: 716–723, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altes TA, Mata J, de Lange EE, Brookeman JR, Mugler JP 3rd. Assessment of lung development using hyperpolarized helium-3 diffusion MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 24: 1277–1283, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashir A, Conradi MS, Woods JC, Quirk JD, Yablonskiy DA. Calibration of RF transmitter voltages for hyperpolarized gas MRI. Magn Reson Med 61: 239–243, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayes T. An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances. Biometrika 45: 296–315. Reprinted from Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (1763) 1753: 1370–1418, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretthorst GL. An introduction to parameter estimation using Bayesian probability theory. In: Maximum Entropy and Bayesian Methods, edited by Fougere PF. Dartmouth, NH: Kluwer Acad. Publ, 1989, p. 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler JP, Loring SH, Patz S, Tsuda A, Yablonskiy DA, Mentzer SJ. Evidence for adult lung growth in humans. N Engl J Med 367: 244–247, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang HK. Convection, diffusion and their interaction in the bronchial tree. Adv Exp Med Biol 227: 39–52, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colebatch HJ, Ng CK. A longitudinal study of pulmonary distensibility in healthy adults. Respir Physiol 65: 1–11, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Clayton PD, Nixon CR. Lung volumes in healthy nonsmoking adults. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir 18: 419–425, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fain SB, Altes TA, Panth SR, Evans MD, Waters B, Mugler JP 3rd, Korosec FR, Grist TM, Silverman M, Salerno M, Owers-Bradley J. Detection of age-dependent changes in healthy adult lungs with diffusion-weighted 3He MRI. Acad Radiol 12: 1385–1393, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galban CJ, Han MK, Boes JL, Chughtai KA, Meyer CR, Johnson TD, Galban S, Rehemtulla A, Kazerooni EA, Martinez FJ, Ross BD. Computed tomography-based biomarker provides unique signature for diagnosis of COPD phenotypes and disease progression. Nat Med 18: 1711–1715, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillooly M, Lamb D. Airspace size in lungs of lifelong non-smokers: effect of age and sex. Thorax 48: 39–43, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glindmeyer HW, Lefante JJ, McColloster C, Jones RN, Weill H. Blue-collar normative spirometric values for Caucasian and African-American men and women aged 18 to 65. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 151: 412–422, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haber PS, Colebatch HJ, Ng CK, Greaves IA. Alveolar size as a determinant of pulmonary distensibility in mammalian lungs. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 54: 837–845, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haefeli-Bleuer B, Weibel ER. Morphometry of the human pulmonary acinus. Anat Rec 220: 401–414, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajari AJ, Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Quirk JD, Conradi MS, Woods JC. Morphometric changes in the human pulmonary acinus during inflation. J Appl Physiol 112: 937–943, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159: 179–187, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartroft WS. Microscopic diagnosis of pulmonary emphysema. Am J Pathol 21: 889–903, 1945. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, Cherniack RM, Rogers RM, Sciurba FC, Coxson HO, Pare PD. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 350: 2645–2653, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 394–418, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito K, Barnes PJ. COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest 135: 173–180, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssens JP, Pache JC, Nicod LP. Physiological changes in respiratory function associated with ageing. Eur Respir J 13: 197–205, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang MR, Fiaux GW, Gillooly M, Stewart JA, Hulmes DJ, Lamb D. Collagen content of alveolar wall tissue in emphysematous and non-emphysematous lungs. Thorax 49: 319–326, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutey BA, Lefrak SS, Woods JC, Tanoli T, Quirk JD, Bashir A, Yablonskiy DA, Conradi MS, Bartel ST, Pilgram TK, Cooper JD, Gierada DS. Hyperpolarized 3He MR imaging: physiologic monitoring observations and safety considerations in 100 consecutive subjects. Radiology 248: 655–661, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massaro D, Massaro GD. Lung development, lung function, and retinoids. N Engl J Med 362: 1829–1831, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonough JE, Yuan R, Suzuki M, Seyednejad N, Elliott WM, Sanchez PG, Wright AC, Gefter WB, Litzky L, Coxson HO, Pare PD, Sin DD, Pierce RA, Woods JC, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Lam SC, Cooper JD, Hogg JC. Small-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 365: 1567–1575, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer RR, Russell ML, Crapo JD. Alveolar septal structure in different species. J Appl Physiol 77: 1060–1066, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller A, Thornton JC, Warshaw R, Anderson H, Teirstein AS, Selikoff IJ. Single breath diffusing capacity in a representative sample of the population of Michigan, a large industrial state. Predicted values, lower limits of normal, and frequencies of abnormality by smoking history. Am Rev Respir Dis 127: 270–277, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller MR. Structural and physiological age-associated changes in aging lungs. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 31: 521–527, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J, Force AET. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 26: 319–338, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narayanan M, Owers-Bradley J, Beardsmore CS, Mada M, Ball I, Garipov R, Panesar KS, Kuehni CE, Spycher BD, Williams SE, Silverman M. Alveolarization continues during childhood and adolescence: new evidence from helium-3 magnetic resonance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 186–191, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochs M, Nyengaard JR, Jung A, Knudsen L, Voigt M, Wahlers T, Richter J, Gundersen HJ. The number of alveoli in the human lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169: 120–124, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osmanagic E, Sukstanskii AL, Quirk JD, Woods JC, Pierce RA, Conradi MS, Weibel ER, Yablonskiy DA. Quantitative assessment of lung microstructure in healthy mice using an MR-based 3He lung morphometry technique. J Appl Physiol 109: 1592–1599, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouriadov A, Farag A, Kirby M, McCormack DG, Parraga G, Santyr GE. Lung morphometry using hyperpolarized (129) Xe apparent diffusion coefficient anisotropy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Magn Reson Med 70: 1699–1706, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouriadov A, Farag A, Kirby M, McCormack DG, Parraga G, Santyr GE. Pulmonary hyperpolarized Xe morphometry for mapping xenon gas concentrations and alveolar oxygen partial pressure: Proof-of-concept demonstration in healthy and COPD subjects. Magn Reson Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quirk JD, Chang YV, Yablonskiy DA. In vivo lung morphometry with hyperpolarized (3) He diffusion MRI: reproducibility and the role of diffusion-sensitizing gradient direction. Magn Reson Med 73: 1252–1257, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quirk JD, Lutey BA, Gierada DS, Woods JC, Senior RM, Lefrak SS, Sukstanskii AL, Conradi MS, Yablonskiy DA. In vivo Detection of Acinar Microstructural Changes in Early Emphysema by 3He Lung Morphometry. Radiology 260: 866–874, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quirk JD, Sukstanskii AL, Bretthorst GL, Yablonskiy DA. Optimal decay rate constant estimates from phased array data utilizing joint Bayesian analysis. J Magn Reson 198: 49–56, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez M, Bur S, Favre A, Weibel ER. Pulmonary acinus: geometry and morphometry of the peripheral airway system in rat and rabbit. Am J Anat 180: 143–155, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreider JP, Raabe OG. Structure of the human respiratory acinus. Am J Anat 162: 221–232, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stocks J, Quanjer PH. Reference values for residual volume, functional residual capacity and total lung capacity. ATS Workshop on Lung Volume Measurements Official Statement of The European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 8: 492–506, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sukstanskii AL, Bretthorst GL, Chang YV, Conradi MS, Yablonskiy DA. How accurately can the parameters from a model of anisotropic 3He gas diffusion in lung acinar airways be estimated? Bayesian view. J Magn Reson 184: 62–71, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sukstanskii AL, Yablonskiy DA. Lung morphometry with hyperpolarized 129Xe: theoretical background. Magn Reson Med 67: 856–866, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verbanck S, Paiva M. Effective axial diffusion in an expansile alveolar duct model. Respir Physiol 73: 273–278, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verbeken EK, Cauberghs M, Mertens I, Clement J, Lauweryns JM, Van de Woestijne KP. The senile lung. Comparison with normal and emphysematous lungs. 1. Structural aspects. Chest 101: 793–799, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang W, Nguyen NM, Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Osmanagic E, Atkinson JJ, Conradi MS, Woods JC. Imaging lung microstructure in mice with hyperpolarized 3He diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med 65: 620–626, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waters B, Owers-Bradley J, Silverman M. Acinar structure in symptom-free adults by Helium-3 magnetic resonance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 847–851, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weibel ER. Morphometry of the Human Lung. New York: Springer, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weibel ER. Morphological basis of alveolar-capillary gas exchange. Physiol Rev 53: 419–495, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.West JB. Respiratory Physiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p. x, 171 p. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Leawoods JC, Gierada DS, Bretthorst GL, Lefrak SS, Cooper JD, Conradi MS. Quantitative in vivo assessment of lung microstructure at the alveolar level with hyperpolarized 3He diffusion MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 3111–3116, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Quirk JD, Woods JC, Conradi MS. Probing lung microstructure with hyperpolarized noble gas diffusion MRI: theoretical models and experimental results. Magn Reson Med 71: 486–505, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yablonskiy DA, Sukstanskii AL, Woods JC, Gierada DS, Quirk JD, Hogg JC, Cooper JD, Conradi MS. Quantification of lung microstructure with hyperpolarized 3He diffusion MRI. J Appl Physiol 107: 1258–1265, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]