Abstract

Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP) is anti-apoptotic, key in development and cancer, however without the typical Bcl2 family members’ structure. Here we report that TCTP contains a BH3-like domain and forms heterocomplexes with Bcl-xL. The crystal structure of a Bcl-xL deletion variant-TCTP11–31 complex reveals that TCTP refolds in a helical conformation upon binding the BH3-groove of Bcl-xL, although lacking the h1-subregion interaction. Experiments using in vitro-vivo reconstituted systems and TCTP+/− mice indicate that TCTP activates the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-xL, in contrast to all other BH3-proteins. Replacing the non-conserved h1 of TCTP by that of Bax drastically increases the affinity of this hybrid for Bcl-xL, modifying its biological properties. This work reveals a novel class of BH3-proteins potentiating the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-xL.

Members of the Bcl2 family of proteins play a critical role in governing the cell death program1. This family of Bcl2 proteins can be functionally divided into the pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins. They contain subdomains that are conserved to variable extend and are called BH domains, because of their homology to Bcl2 (BH: Bcl2 homology domain). As referred to previously2, distant cousins of this family are termed BH3-only proteins and share the third homology domain, typically represented by Bid, Bim, Bad, Puma, Noxa and others as reviewed1. These BH3-only proteins are pro-apoptotic by either activating other pro-apoptotic proteins (Bax and Bak) or inhibiting the anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl2, Bcl-xL, Mcl1, Bcl-w and A1). Hitherto, all known BH3-only proteins binding Bcl-xL inhibit its anti-apoptotic function by a well-established mechanism3, yet there are no BH3-proteins described activating Bcl-xL. Intriguingly the binding of these BH3-proteins to a very similar site on Bax results in the activation of its pro-apoptotic function. It remains completely unknown how the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-xL could be potentiated.

Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein (TCTP/tpt1) is a regulator of pluripotency4, the cancer stem cell compartment5, the tumor reversion program5,6,7,8,9, tumor progression5,6,7,8,9 and certain forms of inflammatory diseases10. It was described as a pro-survival protein by potentiating both Mcl111,12 and Bcl-xL13 and antagonizing the P53 tumor suppressor5. It remains unknown how TCTP regulates Bcl-xL. The initial structural analysis of TCTP indicated that it was highly conserved through phylogeny and could be related to MSS4 without any link to proteins of the Bcl2 family or any others involved in programmed cell death14. Given the importance in cancer of the anti-apoptotic proteins of the Bcl2 family15 of which Bcl-xL is a member and the focus on therapies that inhibit Bcl-xL, it becomes relevant to provide an understanding of any positive regulators of Bcl-xL.

Results

TCTP forms heterotetrameric complexes with Bcl-xL

By using extensive biochemical and biophysical studies (Supplementary Figs 1–6) we show that TCTP forms heterotetrameric complexes with Bcl-xL via crucial interactions between the N-Terminal region of TCTP (TCTP11–31) and the BH3 binding groove of Bcl-xL. Bcl-xL-Y101K mutant, which cannot bind to BH3 domains16, was unable to form heterocomplexes with TCTP suggesting that the interaction is with the BH3 binding pocket on Bcl-xL. ABT-737, a molecule that specifically, and with high affinity, targets the BH3-groove, abrogated formation of the TCTP/Bcl-xL complexes. There was no complex formation between Bcl-xL and full-length TCTP-R21A N-terminal mutant. These results suggest that the N-terminal part of TCTP has a BH3-like domain that interacts with the BH3-groove of Bcl-xL (Supplementary Figs 1–6).

TCTP contains a BH3-like domain

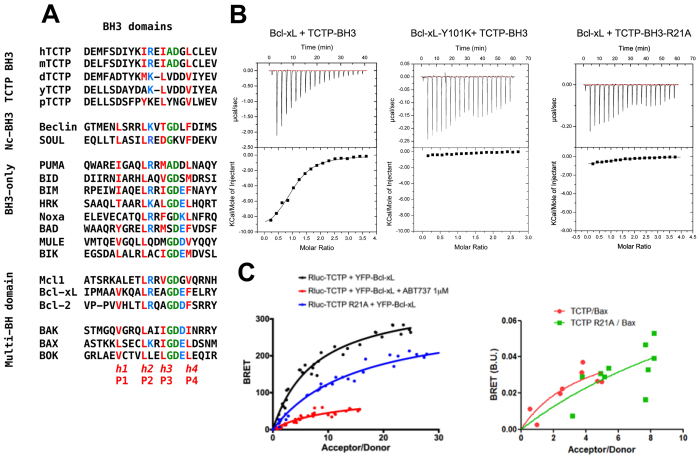

Surprisingly, aligning the amino-acid sequence of the N-terminal region of TCTP with BH3 domains from Bcl-2 family members revealed a putative BH3 domain in TCTP (Fig. 1A), suggesting that this region might bind Bcl-xL. Although the nature of the amino-acids in the h1 (P1) sub-region of the BH3 is not conserved in TCTP, the amino-acids in h2 (P2), h3 (P3) and h4 (P4), including I20, I23 and L27 are homologous to residues found in other BH3-domains that bind to the same hydrophobic groove of Bcl-xL. This putative Bcl-xL-binding domain of TCTP also contains a signature (Gly/Ala)-Asp motif between the h3 (P3) and h4 (P4) positions (Fig. 1A), suggesting that this region of TCTP could interact with the BH3-binding pocket of Bcl-xL.

Figure 1. TCTP contains a non-canonical BH3 domain interacting with the BH3 groove of Bcl-xL.

(A) Sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of TCTP (h:human; m:mouse; d:Drosophila; y:yeast; p:plant) with other BH3 domain containing proteins. In red, the conserved hydrophobic residues of the BH3 domain (named h1 (P1), h2 (P2), h3 (P3) and h4 (P4)). In green, the GD signature of BH3 domains. In blue, the conserved charged residues. (B) Interaction between Bcl-xL and TCTP-BH3 peptides. Calorimetric titration between (left panel) Bcl-xL (0.065 mM) and increasing amount of TCTP-BH3 (1.39 mM); (middle panel) Bcl-xL-Y101K (0.072 mM) and increasing amount of TCTP-BH3 (0.955 mM); (right panel) Bcl-xL (0.065 mM) and increasing amount of TCTP-BH3-R21A (1.26 mM). Each experiment was carried out at 30 °C in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 9. (C) In cellulo BRET analysis between TCTP and Bcl-xL, inhibition by ABT-737, lack of binding for the R21A TCTP to Bcl-xL (left panel) and Bax (right panel).

TCTP’s BH3 domain recognizes the BH3 groove of Bcl-xL

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) (Fig. 1B) shows that TCTP11–31 peptide, containing the putative BH3-domain, binds to Bcl-xL with a dissociation constant of 12 μM. As controls for this interaction, we used two mutants: TCTP11–31-R21A and Bcl-xL-Y101K. TCTP11–31-R21A does not bind to Bcl-xL, and Bcl-xL-Y101K does not bind TCTP11–31 (Fig. 1B). To provide evidence that this interaction between full-length TCTP and Bcl-xL occurs at the cellular level, we measured the close proximity between transiently transfected Luciferase-fused TCTP and YFP-fused Bcl-xL by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET). As shown in Fig. 1C left panel, saturable BRET signals were observed between donor wild type TCTP and increasing levels of acceptor wild type Bcl-xL, indicative of a specific interaction between these proteins. In contrast, we detected no specific BRET signals between donor TCTP and acceptor, YFP-fused BAX, suggesting a lack of interaction between these two proteins (Fig. 1C right panel). BRET signals between TCTP and Bcl-xL were significantly inhibited by treatment of cells with the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 (Fig. 1C left panel), supporting the notion that the interaction relies on the BH3-binding groove of Bcl-xL. Further consistent with this, the R21A mutation in TCTP abrogated BRET signals between full-length TCTP and Bcl-xL (Fig. 1C left panel). Together these results suggest that BH3-TCTP binds to the BH3 groove of Bcl-xL.

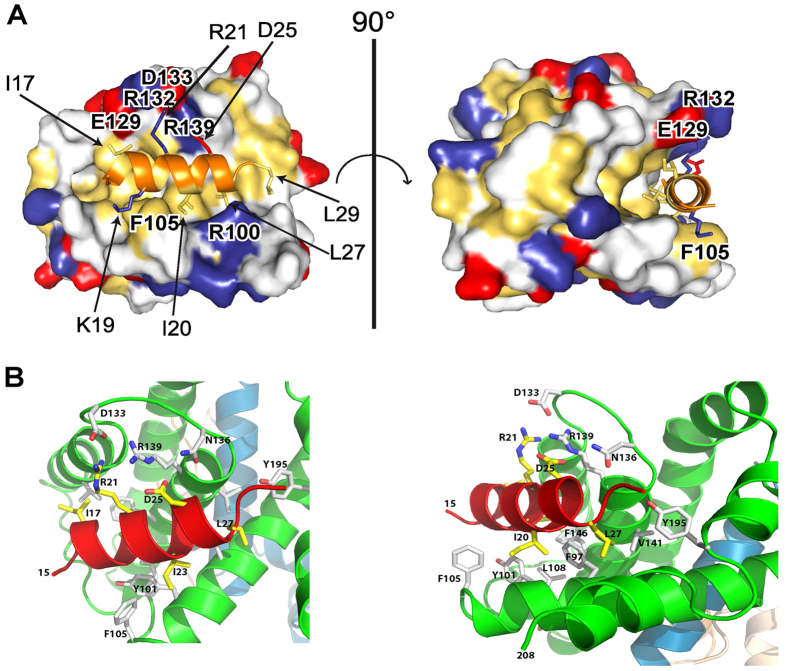

Crystal structure of Bcl-xL bound to BH3 domain of TCTP

To provide structural details of the TCTP/Bcl-xL interaction, the crystal structure of a deletion variant of Bcl-xL (Bcl-xLΔ27–81ΔTM) in complex with TCTP11–31 has been solved and refined at 2.1 Å (Fig. 2A,B, Supplementary Fig. 7 and Table 1). This crystal structure revealed that upon binding to Bcl-xL, the residues 16–27 of TCTP11–31 completely refold into a 3 turn α-helix conformation that binds to the BH3-binding pocket of Bcl-xL, a hydrophobic groove created by helices α2-α5 of Bcl-xL (Fig. 2A,B). In unbound TCTP17, this N-terminal region stabilizes the β-sheet hydrophobic core of the entire TCTP protein (Supplementary Fig. 9). This suggests that the interaction between the full size Bcl-xL and TCTP proteins induces a substantial reorganization of the known TCTP fold.

Figure 2. Crystal structure of Bcl-xL: TCTP-BH3 complex.

(A) Surface diagram showing the interface between Bcl-xL and the TCTP-BH3 peptide. Bcl-xL is in the surface representation. The hydrophobic residues are drawn in yellow, positively charged residues in blue, the negatively charged residues in red, and other in white. The TCTP-BH3 peptide is represented in cartoon and colored in orange. Side chains of residues involved in the binding interface are represented as stick models. (B) Cartoon representation of truncated Bcl-xL bound to TCTP-BH3 domain. Two close views (left and right panel) of the interactions at the interfaces between one TCTP-BH3 peptide and the canonical BH3 groove of Bcl-xL. Residues involved in the interface are indicated and drawn stick models.

Table 1. X-ray Crystallographic Data collection and structure refinement statistics.

| Data collection | |

|---|---|

| X-ray source | ESRF ID29 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97625 |

| Data collection temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | Pilatus 6MF |

| Crystal-detector distance (mm) | 383.18 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 180 |

| Exposure range (°) and time (s) per image | 0.1, 0.04 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.474 |

| Cell parameters (Å) | a = 100.36, b = 100.36, c = 105.04, α = β = γ = 90° |

| Space group | P41212 |

| Resolution range (outer shell) (Å) | 46.50-2.10 (2.23–2.10) |

| Total number of reflections | 404573 (61254) |

| Number of unique reflections | 31973 (4976) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (98.4) |

| Multiplicity | 12.7 (12.2) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 19.2 (1.1) |

| Rmerge | 0.074 (2.2) |

| Rmeas | 0.077 (2.320) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.436) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 37.45 − 2.10 (2.174 − 2.10) |

| R-work/R-free | 0.185 (0.347)/0.221 (0.361) |

| Number of atoms | 3444 |

| Protein; ligands; water | 3377; 10; 57 |

| Protein residues | 418 |

| RMS deviations from ideal bond lengths (Å)* | 0.003 |

| RMS deviations from ideal bond angles (°)* | 0.77 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 98 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 69.10 |

| macromolecules; ligands; solvent | 69.2; 88.10; 59.10 |

| Molprobity Validation | |

| Rotamer and C-beta outliers | 0.3%; 0. |

| Clashscore and Overall score | 2.42; 1.01 |

†mean I/σ(I) falls below 2.0 in the outer shell at 2.2 Å. Rmeas is the redundancy-independent merging R factor. Highest resolution shell is shown in parenthesis.

The main difference in the binding of TCTP to the Bcl-xL groove as compared to other high affinity BH3 proteins such as Bax is the absence of the first turn of the helix, located just before the canonical h1 (P1) motif which is non-conserved in TCTP. The functional relevance of this is addressed in the final part of this work in which this region of TCTP was replaced by the h1 subdomain of Bax.

As observed in complexes of Bcl-xL and other BH3 peptides18,19,20,21,22,23,24, the interaction between Bcl-xL and the BH3 domain of TCTP is mediated by both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions (Fig. 2A,B). The side chain of the hydrophobic residues at the h2 (P2, I20), h3 (P3, I23) and h4 (P4, L27) positions form a network of van der Waals interactions with the Bcl-xL groove (Fig. 2A,B, Supplementary Figs 7,8). Three additional residues, I17, L29 and the side chain of K19 participate in this hydrophobic packing. Of note, since the canonical h1 (P1) is missing in TCTP, I17 might counterbalance this absence by packing with the hydrophobic residues F97, Y101, F105, L108, V126, V141, F146 and Y195 of Bcl-xL in the target-binding pocket formed by helices α2-α5. Furthermore several hydrogen bonds and two salt bridge interactions contribute to the recognition process: (i) R21 of TCTP BH3 domain interacts with E129 and D133 in Bcl-xL; and (ii) D25, part of the (Gly/Ala)-Asp motif between the h3 (P3) and h4 (P4) positions of BH3 domain (Fig. 2A), interacts with R139 in Bcl-xL. These results explain the lack of binding of the TCTP-R21A mutant described above.

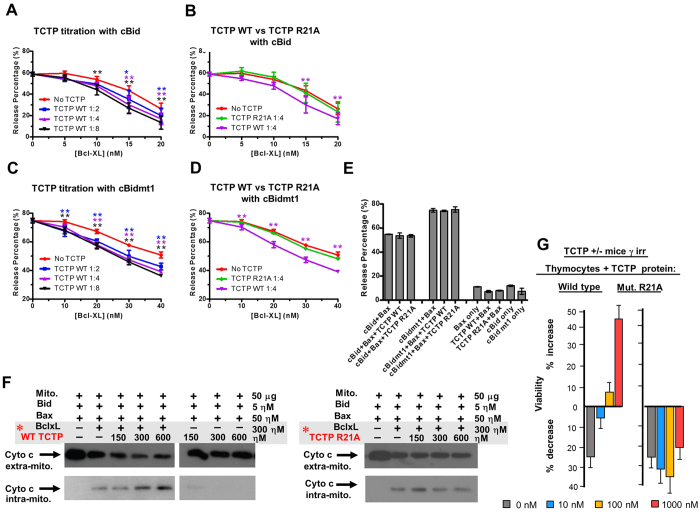

In vitro and in vivo relevance of TCTP BH3 in regulating membrane permeabilization and the apoptotic process

We further tackled the control that TCTP exerts on Bcl-xL in inhibiting Bax, using respectively an in vitro reconstituted system (Fig. 3A–E), then purified mitochondria (Fig. 3F) and thymocytes from TCTP+/− haploinsufficient mice (Fig. 3G). To test the hypothesis that TCTP binding directly to Bcl-xL modifies Bcl-xL function, the impact of TCTP on membrane permeabilization was assayed using a well-established in vitro system in which purified recombinant proteins are used to permeabilize liposomes (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs 10,11, Method summary and statistical analysis, Supplementary Table 2–4)25,26. This purified assay system measures direct interactions in which full-length untagged Bcl-xL inhibits permeabilization by binding full-length caspase 8 cleaved Bid (cBid) and/or full-length untagged Bax, thereby preventing Bax oligomerization in membranes26. To assess the effect of TCTP on Bcl-xL binding directly to Bax we used a mutant Bid (cBidmt1) that binds and activates Bax but does not bind stably to Bcl-xL25,26. In these assays liposome permeabilization by activated Bax releases the entrapped fluorophore/quencher pair 8-aminonaphthalene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (ANTS)/p-xylene-bispyridinium (DPX), resulting in a measurable increase of fluorescence. Recombinant TCTP enhanced Bcl-xL inhibition of both cBid/Bax and cBidmt1/Bax-mediated liposome permeabilization in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A,C). As expected, in control experiments the TCTP R21A mutant protein had no effect on Bcl-xL activity (Fig. 3B,D). In control experiments designed to determine if TCTP affected the activity of cBid/cBidmt1-Bax induced membrane permeabilization, TCTP had no effect in reactions not containing Bcl-xL (Fig. 3E). Similar results were obtained using TCTP11–31 or TCTP11–31 R21A mutant peptides demonstrating that the putative BH3 region in TCTP is sufficient to activate Bcl-xL (Supplementary Figs 10, 11, Method summary and statistical analysis, supplementary Table 2–4). Taken together these results suggest that TCTP potentiates Bcl-xL function by increasing its interaction with Bax, and possibly also with Bid, without interfering with Bid-mediated activation of Bax.

Figure 3. TCTP potentiates Bcl-xL inhibition of Bid/Bax.

(A–E) in vitro reconstitution assay on liposome permeabilization. Increasing concentrations of Bcl-xL were incubated in different molecular ratios [Bcl-xL:TCTP] with TCTP WT (A,C) or with a fixed amount of TCTP R21A (B,D) at pH 9 for 45 min at 37 °C, as specified. The treated Bcl-xL was then added to reactions containing ANTS-DPX liposomes, 100 nM Bax and 20 nM of either cBid (A,B) or cBidmt1(C,D) at pH 7. Liposome permeabilization was quantified by fluorescence after 5h incubation at 37 °C where 100% release was defined as the fluorescence change due to lipid solubilization with 1% Triton X-100. Control reactions demonstrating that TCTP had no measureable effect on the function of any of the proteins other than Bcl-xL contained 320 nM pH9 treated TCTP ANTS/DPX liposomes, 100 nM Bax and 20 nM of cBid or cBidmt1 as indicated (E). Error bars, std. dev. n = 3. To compare between the TCTP treated groups and the Control group statistically, two-way ANOVA test was performed for (A–D) and one-way ANOVA test was performed for (E). Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to calculate the significance of difference between the TCTP treated groups and the corresponding control group (No TCTP for (A–D), cBid+Bax or cBidmt1+Bax for E). Colored asterisks above each data point indicate the statistical significance (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, no asterisks if p ≥ 0.05). A complete statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 2–4. (F) Permeabilization assays of mitochondrial membrane by tBid and Bax assessing cytochrome c release. Sub-optimal amounts of Bcl-xL were added as to inhibit only partially Bax mediated cytochrome c release. Bcl-xL and variants of TCTP were pre-incubated (TCTP ranging from 1.5–6μM and 3 μΜ Bcl-xL framed in gray with red asterisk to highlight the pre-incubation), pH 9, 30 °C then added to the mitochondria at the concentration displayed in the figure. Cyto c intra-mito: mitochondrial fraction. Cyto c extra-mito: in the supernatant, analysed by Western blot. Similar conditions were used for mutant TCTP R21A protein. (G) Rescue of TCTP+/− haploinsufficiency: Thymocytes from TCTP+/− mice were γ-irradiated (γ-irr) (2.5 Gy) and cultured with WT TCTP protein or mutant R21A TCTP at concentrations 0 to 1000 nM.

To examine whether TCTP potentiates the anti-apoptotic effect of Bcl-xL against Bax at the mitochondrial level, we reconstituted the system with purified mitochondria27. When the release of cytochrome c is used as a probe for Bax activity on these mitochondria, we found that wild type TCTP protein (Fig. 3F) and peptide TCTP11–31 (Supplementary Fig. 12), in the presence of Bcl-xL, inhibit cytochrome c release in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3F, Supplementary Fig. 12). TCTP R21A mutant protein (Fig. 3F), TCTP R21A full-length and peptide mutants (Supplementary Fig. 12) or a truncated TCTP peptide (TCTP1–20) (Supplementary Fig. 12), do not potentiate Bcl-xL.

TCTP deficient mice were used to investigate the biological relevance of this interaction in vivo. TCTP knock out mice are embryologically lethal (E 6.5–7) due to increased cell death5,17,28, however heterozygous animals are viable but haploinsufficient5. Typically, the thymocytes of these animals are more sensitive to γ-irradiation5. Thymocytes from irradiated TCTP+/− mice were assessed for their viability in complementation assays in which either TCTP protein or peptide were added. Both, WT TCTP protein (Fig. 3G) and TCTP1–31 peptide (Supplementary Fig. 13), containing the BH3 domain, rescue completely the TCTP+/− haploinsufficient phenotype, reducing the sensitivity to apoptosis to that found in thymocytes of wild type animals (Fig. 3G, Supplementary Fig. 13). This anti-apoptotic function of TCTP is absent in R21A mutants (Fig. 3G, Supplementary Fig. 13). The above experiments were done by taking advantage of the fact that TCTP contains in its NH2 terminus a protein transduction domain (PTD) with the amino-acid sequence MIIYRDLISH 29,30,31. However, all previous experiments were always performed on cell lines and not on cells directly derived from organs. It is therefore completely justified to examine how much of the full-length protein (either WT or mutant) or peptides (WT, mutant and hybrid) are penetrating efficiently irradiated thymocytes directly derived from mice, as it is the case in the present study. In all our constructs, the PTD was placed at the NH2 end of the peptide to be transduced in order to leave the PTD intact and the FLAG sequence was fused C-terminally. The results are shown in Supplementary Figure 14 and illustrate how efficiently TCTP full-length protein and peptides WT, mutant or hybrid are penetrating the irradiated thymocytes. The concentration used for the imaging necessitated higher amounts of peptides than the biological assays which are clearly much more sensitive. The double labeling using rabbit anti-FLAG revealed by anti-rabbit-FITC (Supplementary Fig. 14D) gives a higher background than direct labeling with anti-FLAG phyco-erythrin (Supplementary Fig. 14E-F), but both methods showed that WT or mutant TCTP peptides are equally efficiently incorporated into γ-irradiated thymocytes.

Thus in different experimental systems such as liposomes, purified mitochondria and in ex-vivo cell assays using TCTP+/− haploinsufficient mice, binding of the BH3-region of TCTP to Bcl-xL inhibits more efficiently Bax-mediated membrane permeabilization than does Bcl-xL alone.

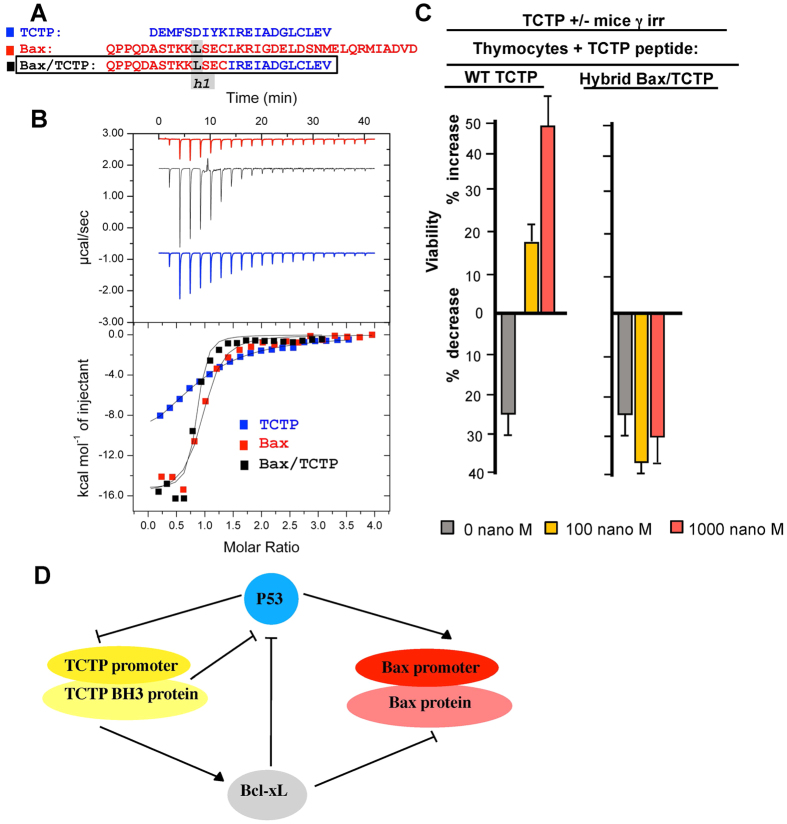

Functional regulation of apoptosis by the non-canonical h1 (P1) sub-region of TCTP’s BH3

Based on the structural data outlined above, it appears that the h1 (P1) sub-region in the BH3- domain of TCTP is not conserved and is not folded as in some of the other known BH3 proteins. This h1 (P1) sub-region from different BH3 family proteins was suggested to be functionally important32. We therefore replaced the h1 (P1) sub-region of BH3-TCTP by that of Bax (Fig. 4A). The Bax peptide binds with relatively high affinity resulting in a measured dissociation constant (Kd) of 200 nM to Bcl-xL, the hybrid TCTP peptide containing the Bax h1 (P1) sub-region has a similar Kd of 500 nM, both of which are much lower than 10–15 μM Kd measured for WT TCTP (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Molecular/functional analysis of the h1 (P1) subregion of BH3-TCTP.

(A) The three BH3 peptides (TCTP in blue, Bax in red and the hybrid Bax/TCTP aligned with the h1 subregion framed). (B) Interaction between Bcl-xL and TCTP-BH3, or Bax or hybrid Bax/TCTP peptides. Calorimetric titration between Bcl-xL (0.043 mM) and increasing amount of TCTP-BH3 (0.75 mM) (blue curve); Bcl-xL (0.006 mM) and increasing amount of Bax (0.117 mM) (red curve); Bcl-xL (0.043 mM) and increasing amount of hybrid Bax/TCTP (0.65 mM) (black curve); Each experiment was carried at 30 °C in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 9. (C) Thymocytes from TCTP+/− mice were γ-irradiated (γ-irr) (2.5 Gy) and cultured in the presence of WT TCTP1–31 peptide, hybrid Bax/TCTP peptide at the indicated concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 nM. (D) Schematic representation of the TCTP/Bcl-xL interaction in the context of the reciprocal feedback loop between P53 and TCTP, sequestering of P53 by Bcl-xL and the control of Bax.

Replacing the h1 subdomain of TCTP by the one found in Bax completely abrogated its anti-apoptotic function when used in a complementation assay with irradiated TCTP+/− haploinsufficient thymocytes, suggesting that this region confers, to a large extent, the anti-apoptotic properties of TCTP’s BH3 domain (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results for the affinities measured by ITC for complexes between WT TCTP/Bcl-xL, Bax/Bcl-xL and the hybrid Bax(h1)-TCTP/Bcl-xL, underline the relevance of the non-canonical h1-subdomain in TCTP.

Discussion

For three decades, there has been converging evidence accumulated for the role played by members of the Bcl2 family in regulating cell death during development, in physiological processes and in diseases, of which most prominently cancer33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. However, the positive regulation and enhancement of the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-xL remains mostly ignored41. In the present study, we report biochemical, structural and biological evidence that underlie this positive regulation of Bcl-xL by TCTP. TCTP is a major anti-apoptotic protein that exerts its activity on one side by direct binding to Bcl2 family members Mcl1 and Bcl-xL11,12,13 and on the other side by engaging into a reciprocal negative feedback loop with p535. This interaction between the N-terminal region and the BH3 domain of Bcl-xL was previously reported, however it was not anticipated at that time by what mechanism this N-terminus of TCTP binds to Bcl-xL13. Thus, at least two major apoptotic pathways are regulated by TCTP, namely the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 family Bcl-xL and Mcl111,12,13,42, and the pro-apoptotic p535. In line with this, it was also described that reprogramming of cancer cells into revertants, which lost the malignant phenotype, parallels a drastic decrease of TCTP6,7,8,9,43. Also, the most aggressive forms of breast cancer have highly elevated levels of TCTP. Normal and cancer breast stem cells have an elevated level of TCTP that warrants their survival, and knocking down TCTP decreases the mammosphere-forming efficiency5. All these processes are closely interconnected with programmed cell death.

In this paper, we show that TCTP forms a heterotetramer with Bcl-xL and we extensively characterized these complexes using biochemical and biophysical methods. We reveal that the formation of the TCTP/Bcl-xl complex is governed by a BH3-like domain present in the N-terminal part of TCTP. The high resolution crystal structure of the purified BH3-TCTP/Bcl-xL complex highlights a substantial refolding/reorganization of the known TCTP fold and reveals at the atomic level how TCTP interacts with the BH3-binding groove of Bcl-xL. Mutational analysis of either the Bcl-xL BH3-binding groove or TCTP supports the structural data and confirms the specificity of this recognition process. Our data suggest that the interaction between the full size Bcl-xL and TCTP proteins should probably induce a substantial reorganization of the known TCTP fold. A reorganization of Bcl-xL folding is also expected, as upon binding to the TCTP BH3 peptide, helix α2 of Bcl-xL elongates and this elongation is accompanied by the flipping of F105 outwards to form a hydrophobic groove that can accommodate the binding of the BH3 peptide, while Y101 is completely buried into the core hydrophobic interface with TCTP BH3 peptide. Examples of a change of conformation of Bcl-xL induced by BH3 binding have been reported. Indeed, BH3 mimetic treatment impacts on Bcl-xL localisation25. Moreover, PUMA-BH3 binding to Bcl-xL partially unfolds it in such a way that its interaction with p53 via a second and distinct site is affected23. Whether this extends to TCTP-BH3 binding to Bcl-xL requires further investigation. In all cases these data and the present work illustrate how secondary structure refolding of proteins, as reported for the widely-known examples of prion proteins44 and few others examples, may be a key event in biology, modulating the conformation of proteins in the cell and generating different active and functional states45,46.

This regulation of the anti-apoptotic process by the BH3 domain of TCTP was further corroborated in in vitro reconstituted systems, where the sole presence of Bax, Bid or Bim, Bcl-xL and TCTP is clearly sufficient to control membrane permeabilization. This was further confirmed on purified mitochondria and for both of these systems a mutation is the BH3 domain of TCTP abrogated its function. This was ultimately evidenced on TCTP heterozygous haploinsufficient mice in which after γ-irradiation, the apoptosis process is rescued by wild type TCTP protein or peptide but not anymore by the mutant. We also tried to understand where resides the major difference between the binding of a negative pro-apoptotic regulator such as Bax and a positive regulator such as TCTP with regard to their respective interaction to Bcl-xL. Bax binds with a much higher affinity to Bcl-xL than TCTP does, and a hybrid mutant where the h1 subregion of TCTP was replaced by this domain from Bax results in a total loss of the positive regulation of Bcl-xL by TCTP. This hybrid mutant was not able anymore to rescue the haploinsufficient phenotype TCTP+/− murine thymocytes following γ-irradiation.

Our data highlight how subtle changes between two BH3 domains, more specifically here in the h1-subdomain, resulting in only a slight difference in the mode of recognition with the BH3 groove of Bcl-xL, reveal a significant increase in binding affinity, hence completely modifying the biological outcome. Combined with the structural analysis (Fig. 2A,B) where this region folds differently into Bcl-xL, these results might suggest a model wherein a rapid exchange of proteins bound to Bcl-xL occurs in favor of Bax/Bcl-xL complexes and, as such, TCTP could prime and activate Bcl-xL against Bax. It should be borne in mind that in exponentially growing cells or cancer cells where apoptosis is inhibited, TCTP levels are extremely high, even above actin47, and that in such conditions low affinity of TCTP/Bcl-xL would be compensated by abundance.

Altogether our results demonstrate that TCTP contains a non-canonical but functional BH3-domain that binds to -and unexpectedly activates- the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-xL. We speculate that activation is achieved by virtue of the low affinity of the interaction as mutations that increase the affinity of the interaction abolish the activity of TCTP. Perhaps, the BH3-TCTP competes with Bcl-xL H9 for the BH3-binding pocket on Bcl-xL, partially activating Bcl-xL. It would not be surprising if other proteins with non-canonical BH3 peptides potentiating the anti-apoptotic effect of specific Bcl2 family members were identified. That BH3-proteins can either increase or decrease the activity of Bcl-xL increases the complexity of the system but also highlights the potential for identification of new therapeutic targets which would not only “hit” the anti-apoptotic proteins but also positive BH3-like regulators. Our demonstration of the interplay between TCTP and Bcl-xL might also shed a new light on the effects of TCTP on p53, of which Bcl-xL is a binding partner5,48. This might connect Bcl-xL and p53 to the regulation of other processes regulated by TCTP, such as cell shape and migration. Of note, it is known that TCTP interacts with the cytoskeleton49, more specifically with centrosomes and indirectly with microtubules50. Moreover, the inverse correlation between TCTP/RhoA and p53/cyclin A/actin expression suggests a common regulation for those proteins and their pathways51. TCTP is also implicated in the epithelial to mesenchymal transition31. From a more comprehensive perspective, accumulating knowledge suggest that TCTP functions as a “smart linker” unifying, regulating and ultimately defining the outcome of a wide variety of biological processes ranging from pluripotency to cell shape, cell death, tumorigenicity and tumor reversion. It exerts its function on a range of target-proteins and the data presented here indicate that both TCTP and the target -at least for TCTP/Bcl-xL- undergo major structural modifications which are probably at the basis of such a widespread biological effect of TCTP.

Methods

Constructs expression and mutagenesis

For expression as a GST-fusion protein, TCTP was cloned into a pHGGWA plasmid52 using the GatewayTM Technology (Invitrogen). The TCTP gene was amplified by PCR and cloned into a pDONR207 plasmid by BP reaction and then subcloned into pHGGWA plasmid by the LR reaction as described in Busso et al.52. See Supplementary Information for full details.

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)

BRET assays were performed as indicated in Bah et al.41. See Supplementary Information for full details.

Protein expression and purification

See Supplementary Information for full details.

Peptides used for in vitro assays and in vivo assays

See Supplementary Information for full details.

Complementation experiments

In order to complement the haploinsufficient TCTP+/− mice with exogenous TCTP, we took advantage of the fact that the first N-terminal fragment of TCTP functions as a Protein Transduction Domain (PTD), enabling TCTP to penetrate into the cell (Supplementary Figs 13–14D) by a mechanism hitherto not well understood30,53,54,55. Thymocytes from wild type or TCTP+/− mice were irradiated (2.5 Gy of γ-irradiation) and cultured overnight in the presence of TCTP protein (Wild type or mutant TCTP protein bearing the mutation R21A) or TCTP peptide (wild type TCTP peptide 1–31, mutant TCTP peptide bearing the mutation R21A, or peptide 1–20) at concentrations ranging from 0–1000 nM.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry experiments

Titrations were done by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assays using an ITC200 calorimeter from GE-Microcal. See Supplementary Information for full details.

Crystallization, X-ray data collection, structure determination, and refinement

High-throughput crystallization screening was performed using a Mosquito liquid transfer robot (TTP Labtech) and the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals were obtained at 20 °C by mixing 0.2 μL of reservoir solution (100 mM Pipes pH 7, 1.5M Tris-sodium citrate) with 0.2 μL of 300 μM of Bcl-xL (Δ27–81ΔCT) + 1 mM TCTP11–31 solution in buffer containing 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 9.3 and by equilibrating the mixture against 40 μl of reservoir solution. A 2.1 Å resolution data set was collected at 100 K on beamline ID29 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility with a Pilatus 6MF detector. The crystal belongs to space group P41212 with unit cell dimensions a = 100.36 Å, b = 100.36 Å, c = 105.04Å and α = β = γ = 90°. Diffraction data were processed, integrated, and scaled with XDS56 and HKL200057. The structure of human Bcl-xL/TCTP11–31 complex was solved by molecular replacement using the program Phenix58 and coordinates from the human Bcl-xL-Beclin complex (Protein Data Bank code 2P1L20) as a search model. The model was built with Coot59 and refined with Phenix58 and Buster60. The statistics are summarized in Table 1. See Supplementary Information for full details. Coordinates of the refined structural model and structure factors have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the accession code 4Z9V.

Interaction experiments

When not specified, proteins tested for binding experiments were mixed at 100 μM, dialyzed against 10 mM CHES pH 9, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT or TCEP, depending on the analysis, and heated overnight at 30 °C.

Gel filtration

For binding experiments, 100 to 200PL of protein mixture were loaded on a size exclusion chromatography (S200, GE Healthcare) column, while elution profiles were measured by UV absorption at 280 nm.

Size-Exclusion Chromatography coupled to Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS)

SEC-MALS experiments were performed on a multi-angle light scattering detector (miniDAWN TREOS, Wyatt Technologies) coupled in-line with SEC and an interferometric refractometer (Optilab T-rEX, Wyatt Technologies). See Supplementary Information for full details.

Native mass spectrometry

Prior to any mass spectrometry experiment, protein buffer was exchanged twice against a 50 mM ammonium acetate (NH4Ac) solution at pH 9.0 using microcentrifuge gel filtration columns (Zeba 0.5 ml, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. NanoESI-MS measurements were carried out on an electrospray quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Synapt G2 HDMS, Waters, Manchester, UK) equipped with an automated chip-based nanoESI source (Triversa Nanomate, Advion Biosciences, Ithaca, NY) operating in the positive ion mode. See Supplementary Information for full details.

in vitro system

purified recombinant proteins are used to permeabilize liposomes as described before25,26. See Supplementary Information for full details.

Cytochrome c release assay

Mitochondria from mouse liver were purified as described by Eskes et al.61. See Supplementary Information for full details.

All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulation. All experimental protocols described in this paper were approved by CNRS and INSERM. All animal studies were carried out in the restricted facilities provided by the CNRS, INSERM and Institut Gustave Roussy, by authorized personnel following the prescribed rules.

Additional Information

Accession numbers: Coordinates of the refined structural model and structure factors have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the accession code 4Z9V.

How to cite this article: Thébault, S. et al. TCTP contains a BH3-like domain, which instead of inhibiting, activates Bcl-xL. Sci. Rep. 6, 19725; doi: 10.1038/srep19725 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the French National Agency for Research (ANR, ANR- 09-BLAN-0292) to AT, RA and JC; CNRS, Université de Strasbourg, INSERM, Instruct, part of the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures (ESFRI) supported by national member subscriptions as well as the French Infrastructure for Integrated Structural Biology (FRISBI) [ANR-10-INSB-05–01, grant ANR-10-LABX-0030-INRT, a French State fund managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche under the frame program Investissements d’Avenir labelled ANR-10-IDEX-0002-02 to JC and IGBMC; European Union Network of Excellence CONTICANET, to AT and RA, LabEx LERMIT to AT and RA, INCa Projets libres de Recherche « Biologie et Sciences du Cancer » 2013 to AT and RA, Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer to AT and RA, Association Sclérose Tubéreuse de Bournevilleand, Odyssea fund to AT and RA; Odyssea fund to AT and RA; Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant FRN12517 to DWA. S.T. was supported by a doctoral fellowship from MESR, Ecole Doctorale de Cancérologie Paris XI and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC). J.S. was supported by a studentship from the Institut de Recherche Servier. A.S.R. was supported by a fellowship from Science without Borders (CNPq), CAPES-COFECUB and Federal University of Paraná (UFPR, Brazil). AT, RA thank Yann Lecluse (IGR, Villejuif) for expert help with the flow cytometry and Smartox Biotechnology for the synthesis of peptides. ST, MA, VC and JC thank the members of the IGBMC common services and the members of the structural biology platform of IGBMC for technical assistance. ST, MA, VC and JC thank members of SOLEIL Proxima1 beamlines and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility–European Molecular Biology Laboratory joint Structural Biology groups for the use of beamlines facilities and for help during X-ray data collection.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.C., R.A. and A.T. conceptualized, designed and directed the study and wrote the article as part of a teamwork with J.-C.M., D.W.A., S.C. and P.J. J.S. and S.C. performed and analyzed the mass spectrometry experiments. X.C. performed the in vitro reconstitution experiments on liposomes and data analysis. J.S., S.M., V.C., T.K. and J.H. A.S.R., I.B.-M., C.B. and N.T.C. performed experiments and data analysis. S.B.T. and C.M.J. performed and interpreted the ITC experiments on the hybrid h1 subdomain of Bax/TCTP F.C. and L.M. performed and interpreted the in cellulo experiments using BRET S.T. and M.A. performed the biochemical and biophysical experiments and participated in writing the article. M.A., V.C. and J.C. performed the structure determination by X-ray crystallography.

References

- Youle R. J. & Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9, 47–59 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar P. E. et al. Bax crystal structures reveal how BH3 domains activate Bax and nucleate its oligomerization to induce apoptosis. Cell 152, 519–531 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldoveanu T., Follis A. V., Kriwacki R. W. & Green D. R. Many players in BCL-2 family affairs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 101–111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol M. J., Garrett N. & Gurdon J. B. Tpt1 activates transcription of oct4 and nanog in transplanted somatic nuclei. Curr. Biol. 17, 801–807 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R. et al. Reciprocal repression between P53 and TCTP. Nat Med 18, 91–99 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuynder M. et al. Biological models and genes of tumor reversion: cellular reprogramming through tpt1/TCTP and SIAH-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14976–14981 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telerman A. & Amson R. The molecular programme of tumour reversion: the steps beyond malignant transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 206–216 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuynder M. et al. Translationally controlled tumor protein is a target of tumor reversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15364–15369 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R., Pece S., Marine J. C., Di Fiore P. P. & Telerman A. TPT1/TCTP-regulated pathways in phenotypic reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol. 23, 37–46 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald S. M., Rafnar T., Langdon J. & Lichtenstein L. M. Molecular identification of an IgE-dependent histamine-releasing factor. Science 269, 688–690 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Li F., Weidner D., Mnjoyan Z. H. & Fujise K. Physical and functional interaction between myeloid cell leukemia 1 protein (MCL1) and Fortilin. The potential role of MCL1 as a fortilin chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37430–37438 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Peng H. W., Cheng Y. S., Yuan H. S. & Yang-Yen H. F. Stabilization and enhancement of the antiapoptotic activity of mcl-1 by TCTP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 3117–3126 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. et al. An N-terminal region of translationally controlled tumor protein is required for its antiapoptotic activity. Oncogene 24, 4778–4788 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaw P. et al. Structure of TCTP reveals unexpected relationship with guanine nucleotide-free chaperones. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 701–704 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juin P., Geneste O., Gautier F., Depil S. & Campone M. Decoding and unlocking the BCL-2 dependency of cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 455–465 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn A. J. et al. Bcl-xL regulates apoptosis by heterodimerization-dependent and -independent mechanisms. EMBO J. 18, 632–643 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susini L. et al. TCTP protects from apoptotic cell death by antagonizing bax function. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1211–1220 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler M. et al. Structure of Bcl-xL-Bak peptide complex: recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science 275, 983–986 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros A. M. et al. Rationale for Bcl-xL/Bad peptide complex formation from structure, mutagenesis, and biophysical studies. Protein Sci. 9, 2528–2534 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberstein A., Jeffrey P. D. & Shi Y. Crystal structure of the Bcl-XL-Beclin 1 peptide complex: Beclin 1 is a novel BH3-only protein. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13123–13132 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W., Huang S., Wu H. & Zhang M. Molecular basis of Bcl-xL’s target recognition versatility revealed by the structure of Bcl-xL in complex with the BH3 domain of Beclin-1. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 223–235 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosi E. et al. Structural changes in the BH3 domain of SOUL protein upon interaction with the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL. Biochem. J. 438, 291–301 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis A. V. et al. PUMA binding induces partial unfolding within BCL-xL to disrupt p53 binding and promote apoptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 163–168 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T. et al. Stabilizing the pro-apoptotic BimBH3 helix (BimSAHB) does not necessarily enhance affinity or biological activity. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 297–302 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranovich A. et al. Differences in the mechanisms of proapoptotic BH3 proteins binding to Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 quantified in live MCF-7 cells. Mol. Cell 45, 754–763 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billen L. P., Kokoski C. L., Lovell J. F., Leber B. & Andrews D. W. Bcl-XL inhibits membrane permeabilization by competing with Bax. PLoS Biol 6, e147 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montessuit S. et al. Membrane remodeling induced by the dynamin-related protein Drp1 stimulates Bax oligomerization. Cell 142, 889–901 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. H. et al. A knockout mouse approach reveals that TCTP functions as an essential factor for cell proliferation and survival in a tissue- or cell type-specific manner. Mol Biol Cell 18, 2525–2532 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Y., Kim S., Pyun H. J., Maeng J. & Lee K. Cellular uptake mechanism of TCTP-PTD in human lung carcinoma cells. Mol. Pharm. 12, 194–203 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Y. et al. The cell penetrating ability of the proapoptotic peptide, KLAKLAKKLAKLAK fused to the N-terminal protein transduction domain of translationally controlled tumor protein, MIIYRDLISH. Biomaterials 32, 5262–5268 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S. Y., Kim H. J., Lee K. J. & Lee K. Translationally controlled tumor protein induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and promotes cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Sci Rep 5, 8061 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. F. et al. The functional differences between pro-survival and pro-apoptotic B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) proteins depend on structural differences in their Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3) domains. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 36001–36017 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto Y., Finger L. R., Yunis J., Nowell P. C. & Croce C. M. Cloning of the chromosome breakpoint of neoplastic B cells with the t(14;18) chromosome translocation. Science 226, 1097–1099 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentman C. L., Shutter J. R., Hockenbery D., Kanagawa O. & Korsmeyer S. J. bcl-2 inhibits multiple forms of apoptosis but not negative selection in thymocytes. Cell 67, 879–888 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veis D. J., Sorenson C. M., Shutter J. R. & Korsmeyer S. J. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell 75, 229–240 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A., Harris A. W. & Cory S. bcl-2 transgene inhibits T cell death and perturbs thymic self-censorship. Cell 67, 889–899 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E. et al. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell 80, 285–291 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsten T. et al. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members bak and bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol. Cell 6, 1389–1399 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvansakul M. et al. A structural viral mimic of prosurvival Bcl-2: a pivotal role for sequestering proapoptotic Bax and Bak. Mol. Cell 25, 933–942 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chipuk J. E. et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science 303, 1010–1014 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bah N. et al. Bcl-xL controls a switch between cell death modes during mitotic arrest. Cell Death Dis 5, e1291 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graidist P., Phongdara A. & Fujise K. Antiapoptotic protein partners fortilin and MCL1 independently protect cells from 5-fluorouracil-induced cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40868–40875 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amson R., Karp J. E. & Telerman A. Lessons from tumor reversion for cancer treatment. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 25, 59–65 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner S. B. Biology and genetics of prions causing neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Genet. 47, 601–623 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmann B. M. et al. An alpha helix to beta barrel domain switch transforms the transcription factor RfaH into a translation factor. Cell 150, 291–303 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giganti D. et al. Secondary structure reshuffling modulates glycosyltransferase function at the membrane. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 16–18 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbeck J. & Blomberg A. Two-dimensional electrophoretic separation of yeast proteins using a non-linear wide range (pH 3-10) immobilized pH gradient in the first dimension; reproducibility and evidence for isoelectric focusing of alkaline (pI > 7) proteins. Yeast 13, 1519–1534 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follis A. V. et al. The DNA-binding domain mediates both nuclear and cytosolic functions of p53. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 535–543 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazile F. et al. Complex relationship between TCTP, microtubules and actin microfilaments regulates cell shape in normal and cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 30, 555–565 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglarz M. K. et al. Association of TCTP with centrosome and microtubules. Biochem Res Int 2012, 541906 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloc M. et al. Inverse relationship between TCTP/RhoA and p53/cyclin A/actin expression in ovarian cancer cells. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 50, 358–367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busso D., Delagoutte-Busso B. & Moras D. Construction of a set Gateway-based destination vectors for high-throughput cloning and expression screening in Escherichia coli. Anal Biochem 343, 313–321 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng J., Kim H. Y., Shin D. H. & Lee K. Transduction of translationally controlled tumor protein employing TCTP-derived protein transduction domain. Anal Biochem 435, 47–53 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins E. O., Schiff D., Mackman N. & Key N. S. Venous thromboembolism in malignant gliomas. J Thromb Haemost 8, 221–227 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. et al. A protein transduction domain located at the NH2-terminus of human translationally controlled tumor protein for delivery of active molecules to cells. Biomaterials 32, 222–230 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. X. D. S. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. & Minor W. In Macromolecular Crystallography. Vol. 276A Methods in Enzymology (eds Carter C. W. & Sweet R. M.) 307–326 (Academic Press, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Adams P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc E. et al. Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNT. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2210–2221 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskes R., Desagher S., Antonsson B. & Martinou J. C. Bid induces the oligomerization and insertion of Bax into the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 929–935 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.