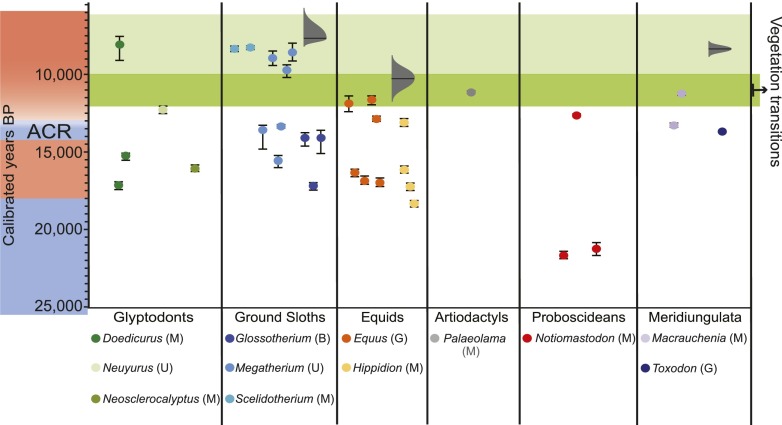

Fig. 2.

Chronology of megafaunal loss, vegetation, and climate change in the Pampas. The diagram shows robust calibrated radiocarbon dates on bone collagen or tooth enamel (the error bars span the 2-σ probability distribution and, for many dates, are too small to appear on the chart). A transition (darker green shading) from an ecosystem dominated by C3 (Pooid) grasses to C4 (Panicoid) grasses begins ∼12,000 y ago and is asynchronous across the Pampas (see Supporting Information for details). The red and blue shading on the left illustrates cool (blue) and warm (red) times. ACR, Antarctic Cold Reversal, which overlaps the northern hemisphere’s Younger Dryas to some extent but is somewhat earlier. Gray distributions indicating the probability of timing of extinction for megafauna were calculated using the GRIWM best-estimate method (59); also see ref. 68. for R-code. GRIWM’s best estimate of the extinction time and its 95% confidence band are younger than 5,000 y ago for glyptodonts (estimated probable timing of extinction: 1,903 calibrated years BP; range: 4,126 to −256 calibrated years BP; the negative number indicates the probability extends into the future) and Notiomastodon (estimated probable time of extinction: 2,415 calibrated years BP; range: 3,001–1,838 calibrated years BP). Clearly, these anomalously young extinction estimates come from a paucity of radiocarbon dates, with those few available being widely spaced in time. Such results do not provide evidence for persistence of megafauna well into the Holocene; rather, they emphasize that more radiocarbon dates are needed. Dietary preferences of extinct megafauna are indicated by G (grazer), B (browser), M (mixed feeder), and U (unknown) (50, 69).