Abstract

Angiosarcomas are rare malignant mesenchymal tumors of endothelial differentiation. The clinical behavior is usually aggressive and the prognosis for patients with advanced disease is poor with no effective therapies. The genetic bases of these tumors have been partially revealed in recent studies reporting genetic alterations such as amplifications of MYC (primarily in radiation-associated angiosarcomas), inactivating mutations in PTPRB and R707Q hotspot mutations of PLCG1. Here, we performed a comprehensive genomic analysis of 34 angiosarcomas using a clinically-approved, hybridization-based targeted next-generation sequencing assay for 341 well-established oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Over half of the angiosarcomas (n = 18, 53%) harbored genetic alterations affecting the MAPK pathway, involving mutations in KRAS, HRAS, NRAS, BRAF, MAPK1 and NF1, or amplifications in MAPK1/CRKL, CRAF or BRAF. The most frequently detected genetic aberrations were mutations in TP53 in 12 tumors (35%) and losses of CDKN2A in 9 tumors (26%). MYC amplifications were generally mutually exclusive of TP53 alterations and CDKN2A loss and were identified in 8 tumors (24%), most of which (n = 7, 88%) arose post-irradiation. Previously reported mutations in PTPRB (n = 10, 29%) and one (3%) PLCG1 R707Q mutation were also identified. Our results demonstrate that angiosarcomas are a genetically heterogeneous group of tumors, harboring a wide range of genetic alterations. The high frequency of genetic events affecting the MAPK pathway suggests that targeted therapies inhibiting MAPK signaling may be promising therapeutic avenues in patients with advanced angiosarcomas.

Keywords: angiosarcoma, genetics, MAPK pathway, MYC

INTRODUCTION

Angiosarcomas are rare malignant mesenchymal tumors of endothelial differentiation [1]. Risk factors for their development include radiation, chronic lymphedema (e.g. Stewart-Trewes Syndrome) and exogenous toxins (e.g. vinyl chlorides, arsenic, etc.). Solar ultraviolet radiation (UV)-exposure is assumed to be a pathogenetic factor for cutaneous tumors which most frequently arise in the head and neck region in the absence of other risk factors. The breast is the most frequent location in which radiation- and lymphedema-associated angiosarcomas arise. Prognosis is poor with a 5-year overall survival of 35% and a median overall survival of 7 months [2]. Treatment with targeted agents such as sorafenib [3-5] and bevacizumab [6] as well as pazopanib [7, 8] has led to transient partial responses or stable disease in selected patients. Clinical trials are currently evaluating tyrosine kinase inhibitors with anti-angiogenic properties including pazopanib (e.g. NCT01462630, NCT02212015, etc.), axitinib (NCT01140737) and regorafenib (NCT02048722). Despite these attempts however, the overall prognosis for patients with advanced angiosarcoma remains poor, and novel mechanism-based, effective therapeutic modalities are needed.

The genetic alterations responsible for the pathogenesis of angiosarcomas are incompletely understood. Whereas characteristic translocations have been identified in many types of sarcoma, none have been described to date in angiosarcomas [9-11]. Amplification of MYC has been reported in a high percentage of post-radiation angiosarcomas (55-100%)[12-14], being considerably less frequent in angiosarcomas arising in the absence of prior radiation therapy [12, 15]. Amplification of FLT4 (18-25%) and KDR mutations (~10%) have also been described [14, 16, 17]. A recent publication described recurrent R707Q hotspot mutations in the PLCG1 gene (3 of 34 tumors, 9%) as well as mutations in PTPRB [18] (10 of 39 tumors, 26%). Recurrent mutations in PLCG1 R707Q in angiosarcomas were confirmed in a subsequent study [19] (3 of 10 tumors, 30%).

To identify potentially novel genetic alterations that play a role in the pathogenesis and to better understand the distribution of known genetic alterations, we comprehensively genotyped a cohort of 34 angiosarcomas. We used a clinically-approved, hybridization-based next-generation sequencing assay targeting 341 known oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [20] and additionally sequenced PLCG1 and PTPRB.

RESULTS

Tumors and patients

Tumor samples were obtained from 34 individuals (24 women, 10 men), with a median age of 69 (range 25-85) years. Angiosarcomas arose in skin (n = 22), liver (n = 4), spleen, kidney, adrenal, thyroid, nasal cavity, lymph node and mediastinum (n = 1 each). In one case the origin was unknown. The samples were primary tumors in 26 cases, 3 were a recurrence, 4 were metastases and in 1 case the sample type was not known. FNCLCC (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer) grades were: grade 1 (n = 1), grade 2 (n = 14) and grade 3 (n = 18). Seven tumors developed following radiation therapy, and 9 tumors arose on the head and neck in areas with considerable cumulative sun exposure.

Genomic alterations (mutations and copy number variations)

Median Sequencing coverage exceeded 165x in 31 tumors. In 3 cases, the median coverage was < 100x, but still allowed identification of hotspot mutations.

MAPK pathway alterations

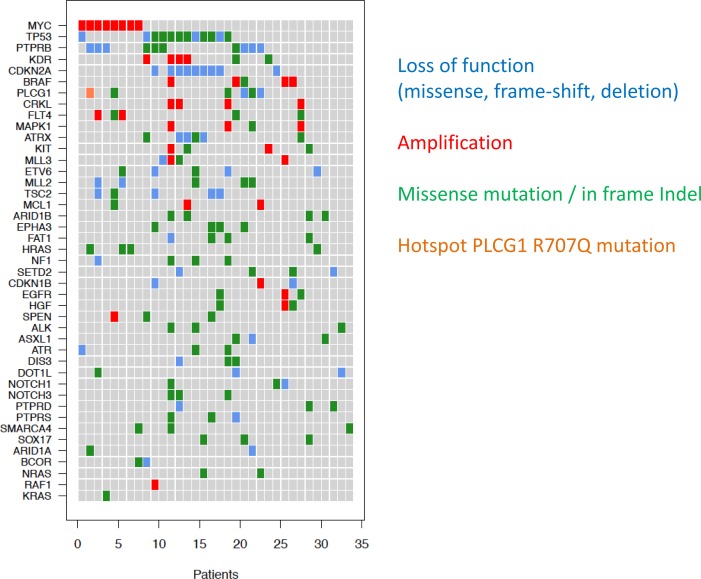

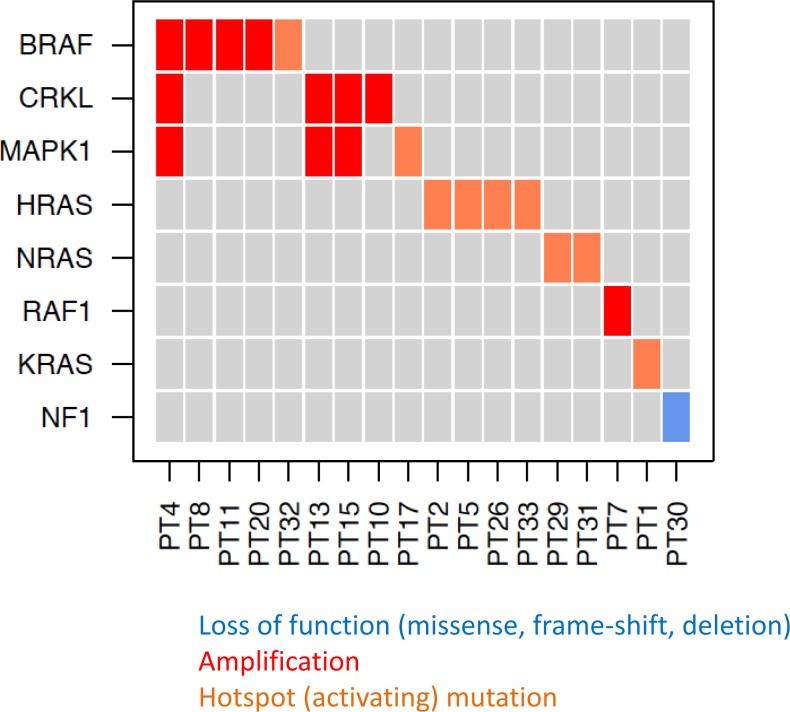

Alterations involving the MAPK pathway were identified in 18 (53%) tumors. In 9 tumors, hotspot mutations in KRAS (G12), HRAS (A59, Q61), NRAS (Q61), BRAF (V600) and MAPK1 (E322) were observed. CNAs, including focal amplifications in MAPK1/CRKL (chr22q11), CRAF (chr3p25) or broad chromosomal gains on chr7 including BRAF were seen in 8 tumors (Figures 1 + 2). One tumor showed an inactivating NF1 intragenic deletion as a mechanism for activating the MAPK pathway. The tumor positive for a KRAS G12D mutation also harbored a known activating GNAQ R183Q mutation, albeit at varying allelic frequencies (KRAS G12D at 6%, GNAQ R183Q at 30%), suggesting that the sample may be heterogeneous and that the KRAS mutant allele may be present in a sub-clone. With the exception of the tumor with GNAQ and KRAS co-mutation, all MAPK-activating hotspot mutations appeared to be mutually exclusive of each other and amplifications of MAPK pathway genes (Figure 3).

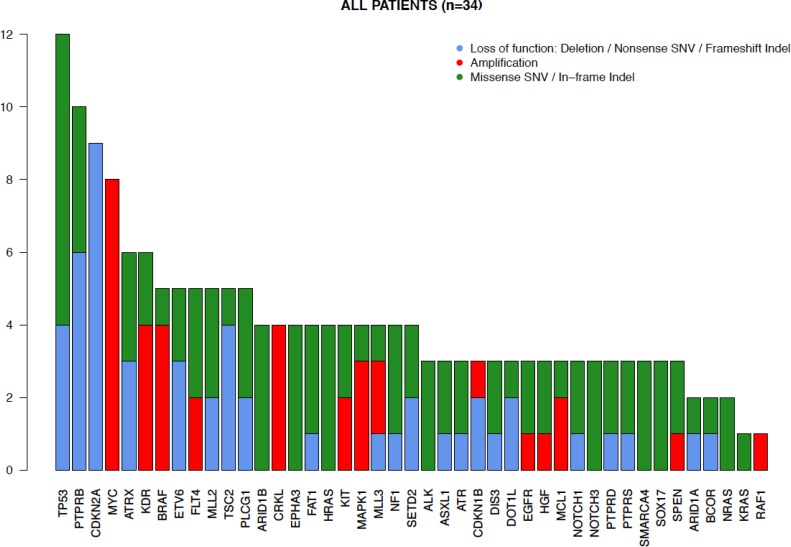

Figure 1. Distribution of genetic alterations in angiosarcomas.

The gene alterations identified in the 34 tumors analyzed are demonstrated in the bar graph. The y-axis depicts the amount of tumor samples harboring the alterations. Loss-of-function (deletion, nonsense single nucleotide variations (SNV) and frameshift mutations or indels) alterations are shown in blue, amplifications in red, and missense SNV or in-frame indels (insertions or deletions) in green.

Figure 2. Co-occurence of mutations in angiosarcoma samples.

Recurrently mutated genes are shown on the y-axis and the samples (patients) on the x-axis. Loss-of-function mutations (missense, frame-shift, deletion) are shown in blue, amplifications in red, missense/in frame indels (insertions or deletions) in green and the hotspot PLCG1 R707Q mutation in orange.

Figure 3. Genetic alterations in angiosarcomas affecting the MAPK pathway.

Loss-of-function mutations (missense, frame-shift, deletion) are shown in blue, amplifications in red, activating mutations in orange.

Additional gene mutations (non-MAPK)

TP53 mutations were the most frequently identified mutations (n = 12, 35%). Virtually all TP53 mutations (n = 11, 92%) were in samples lacking MYC amplifications. PTPRB mutations were identified in 10 samples, and 6 (60% of the mutations, identified in 20% of the tumors) of these were clearly inactivating (nonsense or frameshift) mutations. The putatively activating hotspot mutation in PLCG1 (R707) was observed in one (3%) tumor. Additional loss-of-function mutations were detected in ATRX (n = 4), MLL2 (n = 2) and ASXL1 (n = 1) (Figure 1). Two missense mutations in KDR were identified (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical features and key genetic alterations.

| Case no. | Sex | Age | Site | Tumor type | Associations | Key genetic events | MYC amp | CDKN2A loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 71 | Trunk | Primary | RTX | GNAQ c.547G>A. R183Q; KRAS c.35G>A, p.G12D; PTPRB c.6409C>T, p.Arg2137* | Present | - |

| 2 | F | 79 | Trunk - left axilla | Primary | RTX | PLCG1 c.2120G>A, p.Arg707Gln; PTPRB c.3085G>T, p.Glu1029*; HRAS c.175G>A, p.A59T | Present | - |

| 3 | F | 46 | Trunk - vulva | Primary | CSD | - | Present | |

| 4 | M | 72 | HN - eyelid | Primary | CSD | BRAF amp; CRKL amp; MAPK1 amp; KDR amp | - | Present |

| 5 | F | 68 | Trunk | Recurrence | RTX | HRAS c.175G>A, p.A59T, FLT4 amp | Present | - |

| 6 | F | 74 | HN - nasal cavity | Primary | - | - | ||

| 7 | M | 84 | HN - right temporal | Recurrence | CSD | RAF1 amp | - | Present |

| 8 | F | 30 | Mediastinum | Primary | BRAF amp, KDR c.2159G>C, p.R720P | - | - | |

| 9 | F | 61 | HN - thyroid | Primary | - | - | ||

| 10 | F | 75 | HN | Primary | CSD | CRKL amp; PTPRB c.5713_5714insT, p.Gln1905fs; KDR amp | - | Present |

| 11 | F | 73 | Lower limb - foot | Primary | CSD | BRAF amp | - | - |

| 12 | F | 49 | Not known (cutaneous) | Not known | CSD | - | - | |

| 13 | F | 77 | HN - left neck | Primary | CRKL amp; MAPK1 amp | - | - | |

| 14 | M | 48 | Lung (primary kidney) | Metastasis | KDR c.2312C>A, p.T771K | - | - | |

| 15 | M | 70 | HN - right supraclavicular | Primary | CRKL amp; MAPK1 amp | - | - | |

| 16 | F | 81 | Liver | Primary | KDR amp | - | - | |

| 17 | M | 42 | Lung (primary unknown) | Metastasis | MAPK1 c.964G>A, p.E322K | - | - | |

| 18 | F | 74 | HN | Primary | CSD | - | Present | |

| 19 | M | 68 | HN - orbicularis oculi | Recurrence | - | Present | ||

| 20 | F | 63 | Lower limb - lateral malleolus | Primary | BRAF amp | - | - | |

| 21 | F | 61 | Adrenal gland | Primary | - | - | ||

| 22 | F | 85 | Lower limb | Primary | PTPRB c.6211C>T, p.Gln2071* | - | - | |

| 23 | F | 44 | Trunk | Primary | RTX | Present | - | |

| 24 | F | 64 | Liver | Primary | KDR amp | Present | - | |

| 25 | M | 42 | Liver (primary spleen) | Metastasis | - | Present | ||

| 26 | F | 79 | HN - cheek | Primary | CSD | HRAS c.182A>T, p.Q61L | - | - |

| 27 | F | 73 | Liver | Primary | - | Present | ||

| 28 | M | 56 | Mediastinum (primary leg) | Metastasis | - | - | ||

| 29 | M | 51 | HN - nose | Primary | NRAS c.182A>G, p.Q61R | - | - | |

| 30 | F | 75 | Trunk | Primary | RTX | NF1 deletion (exon 9 and 10); PTPRB c.3565C>T, p.Gln1189*, FLT4 amp | Present | - |

| 31 | M | 25 | Liver | Primary | NRAS c.182A>T, p.Q61L | - | Present | |

| 32 | M | 74 | HN | Primary | CSD | BRAF c.1799T>A, p.V600E; PTPRB c.4311G>A, p.Trp1437* | - | - |

| 33 | F | 83 | Trunk | Primary | RTX | HRAS c.182A>T, p.Q61L | Present | - |

| 34 | F | 54 | Trunk | Primary | RTX | Present | - |

amp = amplification; F = female; M = male; HN = head & neck region; RTX = radiation therapy; CSD = cumulative sun damage

Copy number alterations (non-MAPK)

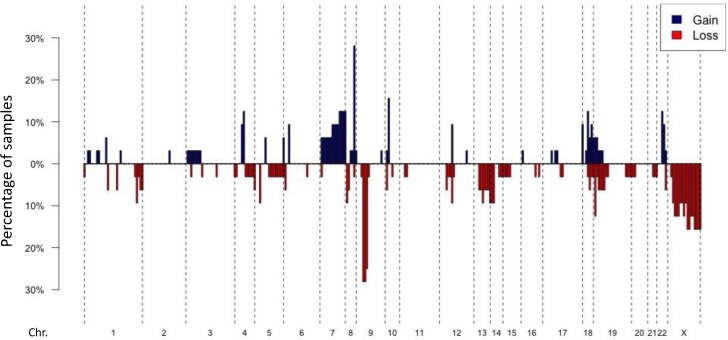

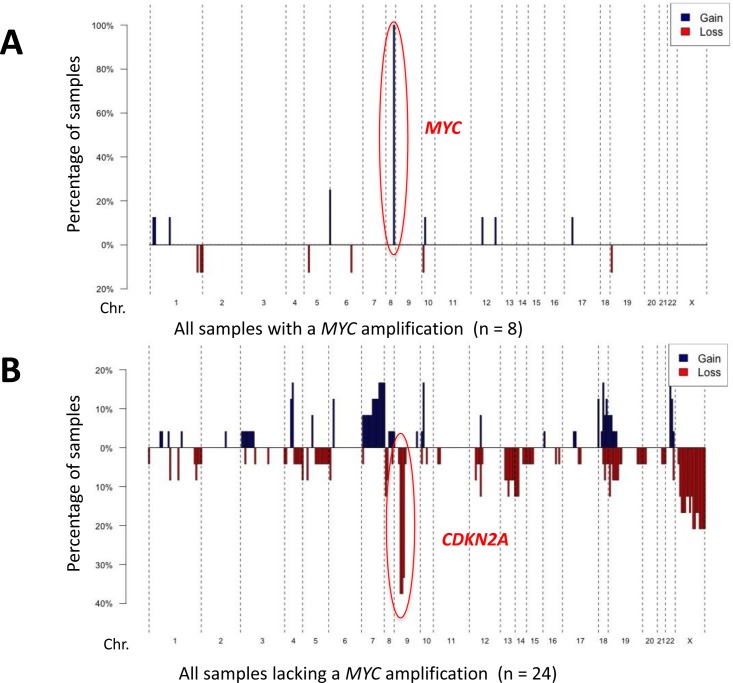

Copy number information was obtained for all samples sequenced by the MSK-IMPACT assay (Figures 4 + 5). Additionally, eight samples were analyzed by array CGH, of which representative examples are shown in Supplemental Figures 1 + 2. The most frequent genetic loss (n = 9, 26%) affected 9p21, which includes the CDKN2A locus (Figures 4 + 5). CDKN2A losses were only found in samples arising without known prior-irradiation, all of which lacked MYC amplifications (Figure 5, Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 4. DNA copy number alterations in angiosarcomas.

Penetration blots of 32 angiosarcomas included in the study (two cases removed due to lower coverage). A fold change value of < −1.5 was applied as a cut off for recognizing a loss and > 1.5 for recognizing a gain. Gains are shown in blue, losses in red. The most frequent gains include MYC on Chr. 8, the most frequent losses CDKN2A on Chr. 9.

Figure 5. Copy number profiles according to MYC status.

Penetration blots of the samples included in the study grouped according to MYC status. A. penetration blot of tumors samples with a MYC-amplification. B. penetrations blot of tumors lacking a MYC-amplification. A fold change value of < −1.5 was applied as a cut-off for recognizing a loss and > 1.5 for recognizing a gain. Gains are shown in blue, losses in red.

Focal MYC amplifications were identified in 8 (24%) angiosarcomas, VEGFR2 (KDR) amplifications in 4 (12%) tumors (Figure 1). Two samples harbored FLT4 amplifications (Figure 5, Supplemental Figure 1). MYC amplifications were significantly more frequent in angiosarcomas known to be associated with previous radiation (7/7 = 100%) than in those with no history of prior irradiation (1/27 = 4%; p < 0.0001). Five cases with MYC amplifications (63%) harbored concurrent MAPK-activating mutations (Figures 2 + 4). Both samples found to have FLT4 amplifications were in MYC amplified tumors arising post-radiation (Supplemental Figure 1). Aside from MYC amplifications, which were identified in all samples with known prior radiation therapy, KLT4 amplifications were also found to be statistically significantly associated with previous radiation exposure (2/7 samples with previous radiation vs. 0/27 without previous radiation; p = 0.004).

DISCUSSION

We identified a number of known genetic alterations in angiosarcomas, including MYC and KLT4 amplifications, RAS mutations, inactivating PTPRB mutations and an activating PLCG1 mutation. In more than half of the tumors, we found genetic alterations activating the MAPK pathway. The clinical ramifications of this finding could be significant, in that MEK inhibitors or other inhibitors of the MAPK pathway may be promising therapeutic approaches for patients with advanced angiosarcoma.

The individual genetic events activating the MAPK pathway were often mutually exclusive (Figure 3), particularly when activating hotspot mutations were present. Generally gene copy number gains are not as strongly activating as mutations leading to constitutive activation of the affected protein, which probably explains why copy number increases in MAPK genes were more frequently found to co-occur than activating mutations. This data strongly supports MAPK pathway alteration being an important common mechanism for angiosarcoma development. Presumably, strong activation of MAPK signaling allows tumor cells to continuously proliferate and, if associated with additional genetic events, transform into a malignant neoplasm. The other 47% of tumors in which no MAPK pathway activating event was identified may harbor genetic events with similar functional consequences; these events might not have been assessed in our current screen and/or may not yet be recognized as oncogenic in human malignancies.

From a therapeutic perspective, our findings provide support for targeting the MAPK pathway in many patients with angiosarcoma. In some cases, mutation-specific therapies may be available (e.g. BRAF V600E). In other cases in which specific inhibitors directly targeting the genetic alterations are not yet available, or no tumor-specific alteration is detected, targeting common downstream molecules of the MAPK pathway, for instance MEK with MEK inhibitors might prove to be a promising therapeutic approach. Potentially combining MAPK pathway inhibitors with other tumor-specific inhibitors, such as agents targeting MYC signaling (in MYC-amplified tumors) has the potential to significantly increase the efficacy of therapeutic regimens.

For a wide range of human malignancies, a very successful alternative therapeutic approach to small molecules with cell intrinsic inhibition of signaling pathways, has been the introduction of immune therapies in particular antibodies inhibiting PD-1 as well CTLA-4 [21-24]. Impressive response rates as well as significant numbers of long-term responses have been reported [23, 25]. Although not currently described to our knowledge, treatment with immunotherapeutic agents such as PD-1 antibodies should be considered as a possible treatment strategy for patients with advanced angiosarcomas.

We identified one activating R183Q hotspot mutation in GNAQ. Activating GNAQ mutations were originally described in melanocytic tumors and frequently occur in blue nevi, uveal melanomas [26] and central nervous system melanocytomas [27, 28]. Recently, exon 4 R183 mutations of GNAQ were identified in port-wine hemangionas and vascular tumors in Sturge-Weber syndrome [29]. These vascular tumors can predispose to the development of angiosarcoma. Unfortunately, in our patient harboring the GNAQ mutation, clinical information about an existing predisposing vascular lesion was not available. It would however be particularly intriguing for future studies to analyze if angiosarcomas arising in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome are found to frequently harbor activating mutations in GNAQ. If this were the case, it could have therapeutic consequences, as approaches targeting downstream activation of GNAQ have shown promise in mouse models of GNAQ-mutated uveal melanoma [30-32] and patients with these tumors have entered clinical trials (NCT01801358). Potentially patients with angiosarcomas harboring GNAQ mutations could benefit from the same therapeutic approaches.

As reported in previous studies [12-14, 17], MYC amplifications were frequent in our cohort (8 of 34 = 24%), further supporting MYC copy number increase as a major activating genetic event in these tumors. MYC copy number increases were found in all seven tumors known to have arisen post-irradiation, strongly supporting MYC amplifications being a major event in this angiosarcoma subtype. However, although MYC clearly appears to play a very relevant role in these tumors, more than half of the MYC-amplified samples (5 of 8) were also found to harbor genetic alterations activating the MAPK pathway (either mutation or copy number gain). Three samples harbored Q61 RAS mutations, one a NF1 deletion and one had concurrent activating GNAQ R183Q and KRAS G12D mutations. The tumor harboring a PLCG1 R707Q mutation also harbored a MYC amplification. These data suggest that in addition to MYC amplifications, ancillary gain-of-function genetic events are necessary to enable full development of an aggressive tumor.

FLT4 amplifications were identified in samples with previous radiotherapy at a frequency (2/7 = 29%) comparable to previous reports (18-25%) [14, 17]. The MYC amplification rate of 100% in tumors arising post-irradiation (7/7) we observed is in line with other studies [13, 14]. Both KDR mutations and amplifications occurred in tumors not known to be radiation associated (Table1, Supplemental Figure 1), with a mutation frequency (6%, n = 2) comparable to previous reports [16]. These data underline the alterations we observed in these genes in our tumor cohort are comparable to findings reported by other groups.

Most TP53 mutations or deletions (11/12, 92%) and all CDKN2A losses occurred in tumors lacking MYC amplification. TP53 mutations are frequent in UV-induced tumors and often carry a UV-signature [33, 34]; 71% of TP53 mutations were C > T alterations, consistent with UV-induction. The distribution pattern may at least in part be explained by different pathogenic mechanisms: UV-exposure predisposing to tumors with TP53 mutations, and radiation predisposing to angiosarcomas with MYC amplifications [12, 13]. Why CDKN2A losses were found only in non-irradiated, non-MYC amplified samples may be more difficult to explain, as UV-exposure is, to our knowledge, not clearly linked to DNA copy number alterations. The distribution does however clearly signify differing pathogenetic mechanisms, with tumors either prone to having TP53 alterations and/or CDKN2A losses, or acquiring MYC amplifications. Future functional studies may reveal the reason for the relative mutual exclusivity of MYC amplifications with alterations of TP53 and CDKN2A.

Recently described mutations affecting PTPRB were found in 10 samples (29%), 4 being missense and 6 inactivating, representing nonsense or frameshift mutations (Table1). As PTPRB consists of well over 6000 base pairs (depending on the splice variant), it is possible the relatively high frequency of mutations observed is at least partly due to the size of the gene (larger genes having a higher chance of acquiring mutations). The frequency of PLCG1 R707Q mutations (1 of 34 = 3%) in our study was lower than in other reports, which have reported mutation frequencies ranging between 9% and 30% [18, 19]. The identification of this mutation in three studies, all leading to an identical amino acid change, indicates that these mutations are relevant pathogenic events in angiosarcoma. Overall, however, these mutations appear to be relatively uncommon, explaining only a minority of cases (pooled frequency of 9% [7 of 78 tumors] from all three studies). Studies analyzing the functional consequences of both PTPRB and PLCG1 will be required before it will be possible to assess whether targeting these mutations may be a viable therapeutic approach for patients with tumors harboring these mutations.

A limitation of our study is that detailed clinical data, including therapy and follow-up information was not available. It would be interesting to see if some of the genetic alterations observed are associated with parameters such as treatment response and patient survival; however, since the genetic alterations identified are very heterogenous, such analysis would require larger sample numbers with detailed clinical follow-up data to allow a meaningful assessment of the clinical consequences of individual genetic alterations.

In summary, our study shows that angiosarcomas are pathogenetically heterogenous tumors, characterized by a range of different genetic events. Whereas the functional and clinical ramifications of some of these events, such as the recently identified PLCG1 and PTPRB mutations will require further study, we found that more than half of the tumors had genetic alterations clearly linked to the MAPK signaling pathway. Almost all currently effective small inhibitor therapeutic approaches in oncology either directly or indirectly dampen the increased signaling output generated by gain-of-function genetic events. Our data showing MAPK-activating events in more than half of angiosarcomas supports the thesis that for patients with these tumors, targeting the MAPK pathway might prove to be a promising therapeutic approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection and histopathology

Angiosarcoma tumor samples were obtained from patients treated in the Department of Dermatology and Pathology of the University Hospital Essen (21 cases), Dermatopathology Duisburg (2 cases) and Dermatopathology Friedrichshafen, Germany (11 cases). Tumor slides were reviewed by at least two experienced histopathologists (T.M., J.S., U.H., K.G.G., R.M.). Histological details are listed in Table 2. The study was done in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the ethics committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Table 2. Pathologic features.

| Case no. | Growth Pattern | Cell type | Vascular structures | Cytologic atypia | TMR | Necrosis | PNI | Grade* | Immunohistochemistry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD31 | CD34 | Other positive markers | |||||||||

| 1 | Fascicles/sheets | Spindle | n.k. | Marked | 13 | - | - | 2 | + | n.k. | |

| 2 | Fascicles/sheets | Spindle/epithelioid | n.k. | Marked | 8 | - | - | 3 | + | n.k. | |

| 3 | Sheets | Primarily spindle | n.k. | Marked | 13 | + | - | 3 | + | + | ERG |

| 4 | Interspersed | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 3 | - | - | 2 | + | n.k. | ERG |

| 5 | Fascicles/sheets | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Marked | 5 | + | - | 3 | + | + | |

| 6 | Sheets | Spindle | Moderate | Marked | 3 | - | - | 3 | + | + | |

| 7 | Fascicles | Epithelioid | Focal | Moderate | 23 | - | - | 2 | + | + | |

| 8 | Fascicles | Epithelioid | Focal | Marked | 6 | - | - | 3 | + | + | |

| 9 | Interspersed | Spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 4 | - | - | 2 | + | - | |

| 10 | Sheets | Spindle/epithelioid | Focal | Marked | 18 | + | + | 3 | + | n.k. | LIVE-1, Prox-1, podoplanin |

| 11 | Interspersed | Epithelioid | n.k. | Marked | 8 | - | - | 3 | + | n.k. | ERG |

| 12 | Sheets | Epithelioid | Absent | Marked | 9 | + | + | 3 | + | n.k. | |

| 13 | Interspersed | Spindle/epithelioid | n.k. | Moderate | 6 | - | - | 2 | + | + | |

| 14 | Interspersed | Spindle | Extensive | Mild | 4 | - | - | 1 | + | + | |

| 15 | Fascicles | Epithelioid | Focal | Moderate | 9 | - | - | 2 | + | n.k. | |

| 16 | Nodular | Epithelioid | Focal | Moderate | 14 | + | - | 2 | + | + | |

| 17 | Nodular | Spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 4 | - | - | 2 | + | + | |

| 18 | Sheets | Epithelioid | Focal | Marked | 15 | - | + | 3 | + | n.k. | ERG |

| 19 | Fascicles | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 4 | - | - | n.k. | + | + | |

| 20 | Fascicles/sheets | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Marked | 8 | + | + | 3 | n.k. | + | |

| 21 | Fascicles/sheets | Epithelioid | Focal | Marked | 5 | - | - | 3 | + | + | |

| 22 | Fascicles/sheets | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Moderate | n.k. | + | - | 2 | + | + | |

| 23 | Nodular | Spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 6 | - | - | 2 | + | n.k. | |

| 24 | Fascicles/sheets | Spindle | Moderate | Marked | 6 | + | - | 3 | n.k. | + | |

| 25 | Sheets | Epithelioid | Focal | Marked | n.k. | - | - | 3 | + | n.k. | |

| 26 | Interspersed | Spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 5 | - | - | 2 | + | n.k. | |

| 27 | Interspersed | Primarily spindle | Extensive | Moderate | 3 | - | - | 2 | + | + | |

| 28 | Interspersed | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Marked | 7 | - | - | 3 | + | - | |

| 29 | Fascicles/sheets | Spindle | Focal | Marked | 4 | + | - | 3 | n.k. | n.k. | |

| 30 | Fascicles/sheets | Spindle | Moderate | Moderate | n.k. | - | + | 2 | + | - | |

| 31 | Fascicles | Spindle | Moderate | Marked | 5 | + | - | 3 | + | + | |

| 32 | Fascicles/sheets | Epithelioid | Moderate | Marked | 12 | + | + | 3 | + | n.k. | |

| 33 | Sheets | Epithelioid | Focal | Marked | 12 | + | + | 3 | + | n.k. | |

| 34 | Interspersed | Primarily spindle | Moderate | Moderate | 7 | - | - | 2 | + | n.k. | |

TMR = tumor mitotic rate per mm2; Grade = histologic grade (1=low, 2=intermediate, 3=high) according to FNCLCC (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer) [49]; PNI= perineural invasion; n.k.=not known (either not assessable on available material or not performed).

DNA isolation

10μm-thick sections were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissues. The sections were deparaffinized and manually microdissected according to standard procedures. Genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA from frozen tissue was directly applied to the Qiagen kit for purification.

Copy number analysis

Array-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) was used to perform analysis of DNA copy number alterations (CNAs) in 8 cases. The methods for hybridization and analysis, including GISTIC 2.0 statistical analysis, have been described previously [35-38]. Whole genome amplification was performed using Sigma's GenomePlex® Single Cell Whole Genome Amplification Kit as described previously [39].

Hybridization-capture based next-generation sequencing for known oncogene mutations

Custom DNA probes were designed for targeted sequencing of all exons and selected introns of 341 oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [20]. Briefly, genomic DNA from tumor samples was used to prepare barcoded libraries using the KAPA HTP protocol (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) and the Biomek FX system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Libraries were pooled, captured and subsequently sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system as paired-end reads. Sequenced reads were trimmed to remove vestigial adaptor sequences using TrimGalore [40], and were aligned to the hg19 human reference genome using BWA [41]. PCR duplicates were removed from the alignment output, and the aligned reads were subjected to local indel realignment and base quality recalibration using GATK [42]. Somatic variant calling was performed using MuTect [43] for single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and SomaticIndelDetector [42] for indels. Significant copy number gains and losses were detected by requiring a greater-than two-fold change in normalized coverage between tumor and a comparator reference FFPE normal. Somatic structural variants were detected using DELLY [44], requiring both paired-end and split-read support.

PLCG1 and PTPRB sequencing

A custom amplicon panel covering the PLCG1 (75 amplicons, covering 4494 of 4613 coding bases) and PTPRB genes (107 amplicons, covering all 7402 coding bases) was designed and prepared applying the GeneRead Library Prep Kit from QIAGEN® according to the manufacturer's instructions. NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Mastermix Set and NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina from New England Biolabs were applied for adapter ligation and barcoding and 24 samples sequenced in parallel on an Illumina MiSeq. Sequence reads were aligned to the human reference sequence (hg19) using BWA and post-processed using tools from GATK and Picard for indel realignment and base quality recalibration. Variant calling for SNVs and indels was performed using a combination of MuTect [43] and Varscan [45]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) corresponding to common population variants were filtered out by removing variants with greater than 1% prevalence in the 1000 genomes cohort. Mutations were reported if they were predicted to result in non-synonymous alterations in protein-coding DNA sequences, and if the overall coverage of the mutation site was ≥50 reads, with ≥20 mutant reads and the variant allele frequency was ≥5%. The criteria for reporting known oncogenic hotspots from COSMIC [46] or TCGA [47, 48] was less stringent: ≥10 mutant reads and variant allele frequency ≥2%.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL FIGURES AND TABLES

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the technical assistance by Nadine Stadler and Nicole Bielefeld.

Footnotes

GRANT SUPPORT

The project was funded in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GR3671/3-1) to KGG, the Werner Jackstädt Stiftung to KGG, and by the Jubilaeumsfonds of the Austrian National Bank (#15461) to TW and by the MSK Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA008748).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Bastian Schilling has received honoraria from Roche and travel support from Bristol-Meyers Squibb. Dirk Schadendorf is on the advisory board or has received honoraria from Roche, Genentech, Novartis, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck. The remaining authors have no disclosures

Authors' contributions

Literature search: R.M., K.G.G., D.S., R.M., T.W., T.M. Study design: R.M., T.M. K.G.G. S.L.S., K.G.G., D.S. Data collection: K.G.G., I.M., S.L.S., M.M., B.S., A.S., T.S., U.H., S.B., J.S., F.G., T.M., T.W. Data analysis: K.G.G., D.C., R.C., T.W., R.M., M.M., T.M. Data interpretation: K.G.G., R.M., R.C., D.C., T.W., M.M., D.S., S.B., B.S., M.B., K.H, A.V., M.P., N.S., N.B. Manuscript writing: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young RJ, Brown NJ, Reed MW, Hughes D, Woll PJ. Angiosarcoma. The lancet oncology. 2010;11:983–991. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frith AE, Hirbe AC, Van Tine BA. Novel pathways and molecular targets for the treatment of sarcoma. Current oncology reports. 2013;15:378–385. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maki RG, D'Adamo DR, Keohan ML, Saulle M, Schuetze SM, Undevia SD, Livingston MB, Cooney MM, Hensley ML, Mita MM, Takimoto CH, Kraft AS, Elias AD, Brockstein B, Blachere NE, Edgar MA, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with metastatic or recurrent sarcomas. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:3133–3140. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Mehren M, Rankin C, Goldblum JR, Demetri GD, Bramwell V, Ryan CW, Borden E. Phase 2 Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial (S0505) of sorafenib in advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 2012;118:770–776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray-Coquard I, Italiano A, Bompas E, Le Cesne A, Robin YM, Chevreau C, Bay JO, Bousquet G, Piperno-Neumann S, Isambert N, Lemaitre L, Fournier C, Gauthier E, Collard O, Cupissol D, Clisant S, et al. Sorafenib for patients with advanced angiosarcoma: a phase II Trial from the French Sarcoma Group (GSF/GETO) The oncologist. 2012;17:260–266. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, von Mehren M, Jovanovic BD, Brockstein BE, Evens AM, Benjamin RS. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO. 2013;24:257–263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azzariti A, Porcelli L, Mangia A, Saponaro C, Quatrale AE, Popescu OS, Strippoli S, Simone G, Paradiso A, Guida M. Irradiation-induced angiosarcoma and anti-angiogenic therapy: a therapeutic hope? Experimental cell research. 2014;321:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo KH, Kim HS, Lee SJ, Park SH, Kim SJ, Kim SH, La Choi Y, Shin KH, Cho YJ, Lee J, Rha SY. Efficacy of pazopanib monotherapy in patients who had been heavily pretreated for metastatic soft tissue sarcoma: a retrospective case series. BMC cancer. 2015;15:154. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor BS, Barretina J, Maki RG, Antonescu CR, Singer S, Ladanyi M. Advances in sarcoma genomics and new therapeutic targets. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:541–557. doi: 10.1038/nrc3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertens F, Panagopoulos I, Mandahl N. Genomic characteristics of soft tissue sarcomas. VirchowsArchiv: an international journal of pathology. 2010;456:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0736-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mertens F, Antonescu CR, Hohenberger P, Ladanyi M, Modena P, D'Incalci M, Casali PG, Aglietta M, Alvegard T. Translocation-related sarcomas. Seminars in oncology. 2009;36:312–323. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, Mossinger K, Kuffer S, Sauer C, Belharazem D, Zettl A, Coindre JM, Hallermann C, Hartmann JT, Katenkamp D, Katenkamp K, Schoffski P, Sciot R, Wozniak A, et al. MYC high level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. The American journal of pathology. 2010;176:34–39. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mentzel T, Schildhaus HU, Palmedo G, Buttner R, Kutzner H. Postradiation cutaneous angiosarcomaafter treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicopathological, immunohistochemicaland molecular analysis of 66 cases. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2012;25:75–85. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo T, Zhang L, Chang NE, Singer S, Maki RG, Antonescu CR. Consistent MYC and FLT4 gene amplification in radiation-induced angiosarcoma but not in other radiation-associated atypical vascular lesions. Genes, chromosomes &cancer. 2011;50:25–33. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shon W, Sukov WR, Jenkins SM, Folpe AL. MYC amplification and overexpression in primary cutaneous angiosarcoma: a fluorescence in-situ hybridization and immunohistochemical study. Modern pathology: an official journal of theUnited States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2014;27:509–515. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonescu CR, Yoshida A, Guo T, Chang NE, Zhang L, Agaram NP, Qin LX, Brennan MF, Singer S, Maki RG. KDR activating mutations in human angiosarcomas are sensitive to specific kinase inhibitors. Cancer research. 2009;69:7175–7179. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornejo KM, Deng A, Wu H, Cosar EF, Khan A, St Cyr M, Tomaszewicz K, Dresser K, O'Donnell P, Hutchinson L. The utility of MYC and FLT4 in the diagnosis and treatmentof postradiation atypical vascular lesion and angiosarcoma of the breast. Human pathology. 2015;46:868–875. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behjati S, Tarpey PS, Sheldon H, Martincorena I, Van Loo P, Gundem G, Wedge DC, Ramakrishna M, Cooke SL, Pillay N, Vollan HK, Papaemmanuil E, Koss H, Bunney TD, Hardy C, Joseph OR, et al. Recurrent PTPRB and PLCG1 mutations in angiosarcoma. Nature genetics. 2014;46:376–379. doi: 10.1038/ng.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunze K, Spieker T, Gamerdinger U, Nau K, Berger J, Dreyer T, Sindermann JR, Hoffmeier A, Gattenlohner S, Brauninger A. A Recurrent Activating PLCG1 Mutation in Cardiac Angiosarcomas Increases Apoptosis Resistance and Invasivenessof Endothelial Cells. Cancer research. 2014;74:6173–6183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, Shah RH, Benayed R, Syed A, Chandramohan R, Liu ZY, Won HH, Scott SN, Brannon AR, O'Reilly C, Sadowska J, Casanova J, Yannes A, Hechtman JF, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. The Journal of molecular diagnostics: JMD. 2015;17:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, Leming PD, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Drake CG, Pardoll DM, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, Pitot HC, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Martins R, Eaton K, Chen S, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K, Burke MM, Caldwell A, Kronenberg SA, Agunwamba BU, Zhang X, Lowy I, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maio M, Grob JJ, Aamdal S, Bondarenko I, Robert C, Thomas L, Garbe C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Testori A, Chen TT, Tschaika M, Wolchok JD. Five-year survival rates for treatment-naive patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in a phase III trial. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33:1191–1196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, Garrido MC, Vemula S, Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Wackernagel W, Green G, Bouvier N, Sozen MM, Baimukanova G, Roy R, Heguy A, Dolgalev I, Khanin R, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:2191–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murali R, Wiesner T, Rosenblum MK, Bastian BC. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations in melanocytomas of the central nervous system. Acta neuropathologica. 2012;123:457–459. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0948-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusters-Vandevelde HV, Klaasen A, Kusters B, Groenen PJ, van Engen-van Grunsven IA, van Dijk MR, Reifenberger G, Wesseling P, Blokx WA. Activating mutations of the GNAQ gene: a frequent event in primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous system. Acta neuropathologica. 2010;119:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, Baugher JD, Frelin LP, Cohen B, North PE, Marchuk DA, Comi AM, Pevsner J. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:1971–1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu FX, Luo J, Mo JS, Liu G, Kim YC, Meng Z, Zhao L, Peyman G, Ouyang H, Jiang W, Zhao J, Chen X, Zhang L, Wang CY, Bastian BC, Zhang K, et al. Mutant Gq/11 promote uvealmelanoma tumorigenesis by activating YAP. Cancer cell. 2014;25:822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng X, Degese MS, Iglesias-Bartolome R, Vaque JP, Molinolo AA, Rodrigues M, Zaidi MR, Ksander BR, Merlino G, Sodhi A, Chen Q, Gutkind JS. Hippo-independentactivation of YAP by the GNAQ uveal melanoma oncogene through a trio-regulated rho GTPase signaling circuitry. Cancer cell. 2014;25:831–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Wu Q, Tan L, Porter D, Jager MJ, Emery C, Bastian BC. Combined PKC and MEK inhibition in uveal melanoma with GNAQ and GNA11 mutations. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brash DE, Rudolph JA, Simon JA, Lin A, McKenna GJ, Baden HP, Halperin AJ, Ponten J. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the UnitedStates of America. 1991;88:10124–10128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ouhtit A, Ueda M, Nakazawa H, Ichihashi M, Dumaz N, Sarasin A, Yamasaki H. Quantitative detection of ultraviolet-specific p53 mutations in normal skin from Japanese patients. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsoredby the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 1997;6:433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Murali R, Fried I, Griewank KG, Ulz P, Windpassinger C, Wackernagel W, Loy S, Wolf I, Viale A, Lash AE, Pirun M, Socci ND, Rutten A, Palmedo G, et al. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nature genetics. 2011;43:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/ng.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, Vivanco I, Lee JC, Huang JH, Alexander S, Du J, Kau T, Thomas RK, Shah K, Soto H, Perner S, et al. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: methodology and application to glioma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, Mc Henry KT, Pinchback RM, Ligon AH, Cho YJ, Haery L, Greulich H, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome biology. 2011;12:R41. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geigl JB, Speicher MR. Single-cell isolation from cell suspensions and whole genome amplification from single cells to provide templates for CGH analysis. Nature protocols. 2007;2:3173–3184. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krueger F. Trim Galore: A wrapper script to automate quality and adapter trimming as well as quality control 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nature biotechnology. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rausch T, Zichner T, Schlattl A, Stutz AM, Benes V, Korbel JO. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:i333–i339. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome research. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P, Leung K, Bindal N, Boutselakis H, Ding M, Bamford S, Cole C, Ward S, Kok CY, Jia M, De T, Teague JW, Stratton MR, McDermott U, et al. COSMIC: exploring the world's knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43:D805–811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Integrative analysis of complex cancergenomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Science signaling. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coindre JM. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: review and update. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2006;130:1448–1453. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1448-GOSTSR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.