Abstract

The mechanisms that limit the speed at which striated muscles relax are poorly understood. This work presents, to our knowledge, novel simulations that show that the time course of relaxation is accelerated by interfilamentary movement resulting from series compliance; force drops faster when myosin heads move relative to actin during relaxation. This insight was obtained by using cross-bridge distribution techniques to simulate the mechanical behavior of half-sarcomeres that were connected in series with springs of varying stiffness. (The springs mimic the combined effects of half-sarcomere heterogeneity and muscle’s series elastic component.) Half-sarcomeres that shortened by >∼10 nm when they were activated subsequently relaxed with a biphasic profile; force initially declined slowly and approximately linearly before collapsing with a fast exponential time course. Stretches imposed during the linear phase quickened relaxation, while shortening movements prolonged the time course. These predictions are consistent with data from experiments performed by many other groups using single muscle fibers and isolated myofibrils. When half-sarcomeres were linked to stiff springs (so that they did not shorten appreciably during the simulations), force relaxed with a slow exponential time course and did not show biphasic behavior. Together, these results suggest that fast relaxation of striated muscle is an emergent property that reflects multiscale interactions within the muscle architecture. The nonlinear behavior during relaxation reflects perturbations to the dynamic coupling of regulated binding sites and cycling myosin heads that are induced by interfilamentary movement.

Introduction

Skeletal and cardiac muscles relax after an isometric contraction with a biphasic profile; force drops slowly and approximately linearly at the very beginning of relaxation and then collapses with an exponential time course. This behavior has been recognized for almost a century (1) but remains poorly understood (2, 3). Huxley and Simmons (4) obtained an important insight by demonstrating that the ends of a single fiber elongate as force transitions from the slow to the fast phase of relaxation. This suggests that the development of inhomogeneous strain patterns may influence the rate of force decline. Subsequent experiments using isolated myofibrils support this hypothesis and show that the fast phase of relaxation can be initiated by sudden yielding of a single half-sarcomere (5). (Interestingly, unlike the situation in intact fibers, half-sarcomeres near the center of a myofibril can yield first.) Together, these results imply that the time course of relaxation may be determined by the effects of interfilamentary movement on cross-bridge cycling kinetics (6, 7). This article describes computer simulations that were developed to test the hypothesis and to predict how different sarcomeric mechanisms influence relaxation.

Materials and Methods

The calculations illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 and in Figs. S1–S6 in the Supporting Material were performed using MyoSim software (9). The simulations used the simple two-state myosin scheme shown in Fig. 1 A of Campbell (9). As described in Eq. 3 of the same article, the rate of change of N, the number of binding sites on actin, was defined as

| (1) |

where aon and aoff are rate constants, Noverlap is the maximum number of binding sites that heads could potentially interact with (defined by the arrangement of the thick and thin filaments within the half-sarcomere), and Nbound is the number of sites that have a head bound. kplus is a constant that defines the strength of positive cooperativity whereby bound myosin heads recruit additional binding sites to the available state. Note that in this work, the kminus constant described in Campbell (9) was set to zero for simplicity. This means that binding sites that were unavailable for myosin attachment did not suppress other sites from activating.

Figure 1.

A half-sarcomere connected in series with a compliant spring relaxes with a biphasic profile. (A) Model framework. (B) Rate functions for myosin attachment (f) and detachment (g). (C) Simulations fitted to experimental data digitized from records published by Piroddi et al. (8) that were obtained from a single myofibril isolated from human ventricular myocardium. The bottom panel shows the proportion of binding sites on actin that were available for myosin heads to attach to (solid line) and that were bound (dotted line). To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 2.

The time course of relaxation depends on the stiffness of the series elasticity. Half-sarcomeres linked to very stiff or very compliant springs did not exhibit biphasic relaxation. β0 is the value of β shown in Table S1.

Figure 3.

Interfilamentary movement distorts the distribution of attached cross-bridges. (A) Activation and (B) relaxation phases of the simulation shown in Fig. 1. The surface plots on the right-hand side illustrate how the cross-bridge distributions evolved during the simulation. As the half-sarcomere relengthened during the relaxation phase, cross-bridges are displaced to positions where they detach very quickly. (C and D) As above, but showing a simulation without series compliance. The cross-bridge distributions are not perturbed by interfilamentary filament and the muscle relaxes slowly with an exponential time course. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

Stretches shorten the linear phase of relaxation. (A) Simulations showing that step length changes imposed soon after the Ca2+ concentration are reduced alter the time course of relaxation. (B) Analysis of simulations with step length changes of different sizes. The duration of the slow linear phase was defined as the time interval from the step reduction in Ca2+ to the time at which the first derivative of force with respect to time had its greatest negative value. To see this figure in color, go online.

The force produced by a series elastic element of length xs was

| (2) |

where α and β are model parameters. The forces produced by the half-sarcomere and the series elastic element (Fig. 1 A) were balanced in the computer calculations using a technique based on Newton’s method (10).

Myosin heads attached to binding sites at a rate f (Fig. 1 B) that depended on the length x of the cross-bridge link (Fig. 1 A of Campbell (9)). The value f was defined as

| (3) |

where F is a parameter that sets the maximum attachment rate, kcb is the stiffness of the cross-bridge link, kB is Boltzmann’s constant (1.381 × 10−23 J K−1), and T is the experimental temperature (assumed to be 288 K). Myosin heads detached from binding sites at a rate g (Fig. 1 B) that was defined as

| (4) |

where G sets the detachment rate for an unstrained cross-bridge link, and g+, g−, and s are model parameters. The value s defines the slope of the sigmoid functions and was set to 5 nm−1. Simulations used time steps of no more than 1 ms so these relationships meant that cross-bridges detached immediately if they were stretched past g+ or shortened beyond g−.

Different functional forms of g(x) including polynomials and exponential functions were tested in preliminary simulations and produced qualitatively similar results (data not shown). Compliance accelerates relaxation if cross-bridges detach more quickly as they are strained. This basic result does not depend on the precise shape of g(x).

The experimental data shown in Figs. 1 C and 5 B are representative of many similar experiments from the literature. The data were digitized from figures published by Piroddi et al. (8) and were obtained by these authors using a single myofibril isolated from a human cardiac ventricle. The activation phase was replotted from Fig. 2 b of Piroddi et al. (8), The relaxation phase was replotted from Fig. 4 A.

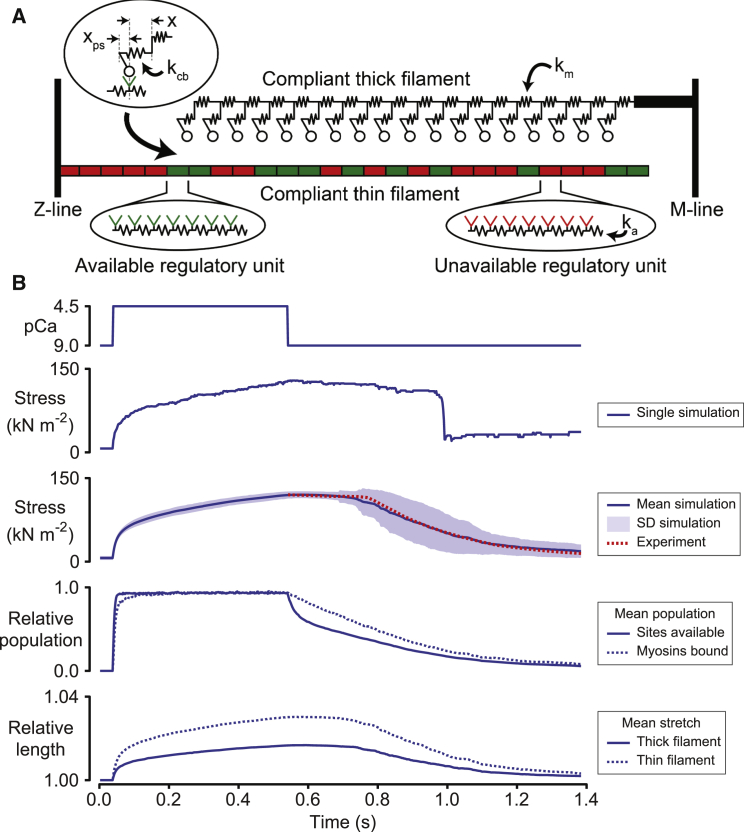

Figure 5.

Filament extensibility can potentially contribute to biphasic relaxation. (A) Schematic showing one compliant thick filament and one compliant thin filament. The force in a single cross-bridge link was defined as kcb (x + xps), where kcb is the stiffness of the link, x is the cross-bridge displacement, and xps is the cross-bridge power stroke. The force generated by the filament system was calculated as the product of the thick filament spring constant km and the extension of the thick filament spring nearest the M-line. The spring constant for thin filament segments was ka. (B) Results of simulations fitted to the relaxation phase of the experimental data (8) plotted in Fig. 1. Because the calculations use stochastic techniques (11), the predicted behavior of the system depended on the initial mathematical conditions that were set by a randomly generated seed. The force record labeled “Single simulation” shows the results of one trial. The panel below the single simulation data shows the mean and standard deviation of 100 force records calculated using different seeds. The mean force record matched the experimental data closely. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 1 C shows the result of fitting the MyoSim model to the experimental data. The fitting was performed by adjusting the values of 11 model parameters using a simplex search method (12) to minimize the least-squares difference between the experimental data and the simulated force trace (13, 14). The parameter values obtained through this procedure are listed in Table S1 in the Supporting Material.

A separate set of simulations is summarized in Fig. 5. These calculations modeled pairs of compliant thick and thin filaments using algorithms that have already been described in detail (11). Each thick filament was modeled as a chain of 18 myosin heads joined by linear springs of stiffness km. Thin filaments were composed of 189 binding sites organized into 27 regulatory units. Each binding site was joined to its neighbors by linear springs of stiffness ka. The geometry is based on the simple assumptions that myosin heads can only interact with actin monomers that they are directly facing, and that only one head from each dimer can bind at a time. Other groups have published simulations of more complex filament architectures (15, 16). All of the sites in a regulatory unit switched between the available and unavailable states at the same time. Sites could not switch to the unavailable state if one of the sites in the regulatory unit was bound by a myosin head. Because each thick filament is surrounded by six thin filaments in a real myofibrillar lattice, the forces predicted by the model were converted to stress values by multiplying by six times the thick filament density (0.407 × 1015 m−2; Linari et al. (17)).

The force records predicted using this model were fitted to the relaxation data published by Piroddi et al. (8) as described for the earlier calculations. The parameters values obtained through this procedure are listed in Table S2.

MyoSim software can be downloaded from http://www.myosim.org. The code used to simulate pairs of compliant thick and thin filaments can be downloaded from http://www.campbellmusclelab.org/software.

Results

Numerous experiments performed using fibers (for example, Edman and Reggiani (18)) and isolated myofibrils (for example, Rassier and Pavlov (19)) show that the central segment of the preparation shortens as it develops force. This can reflect compliance in the attachments to the apparatus (20), muscle’s series elastic component (21, 22), or half-sarcomere heterogeneity (23) (where half-sarcomeres in the middle of the preparation shorten by stretching half-sarcomeres near the ends). For simplicity, these different sources of compliance were combined and mimicked using a single spring. The spring was connected in series with a published model of cycling cross-bridges (Fig. 1 A).

Multidimensional optimization was then performed to fit the force record predicted by the model to representative experimental data obtained by Piroddi et al. (8) from human ventricular myofibrils. The values of 11 parameters describing the biophysical properties of the thick and thin filaments and the series compliance were adjusted during this process (Table S1). The force record produced by the optimized model matched the experimental data closely and reproduced the characteristic biphasic relaxation (Fig. 1 C).

The time course of relaxation depended on the stiffness of the series spring (Fig. 2). If the component was almost rigid, the half-sarcomere did not shorten as it developed force and the system subsequently relaxed with a slow exponential time course. Half-sarcomeres that shortened against a very compliant spring also relaxed slowly. Fig. S1 shows that intermediate values of series compliance reduced the time to 90% relaxation to one-third of the value predicted for a rigid system.

Fig. 3 shows how the distributions of attached cross-bridges evolved during simulations with different amounts of series elasticity. When the system was compliant, the transition to the fast relaxation phase was accompanied by sudden lengthening and subsequent detachment of cross-bridge links (Fig. 3 B). Force dropped quickly because the cross-bridges were pulled to positions where they had a fast detachment rate. When the system was rigid, the cross-bridge populations were not perturbed by interfilamentary movement and force dropped with a slow exponential time course (Fig. 3 D).

Further calculations showed that the linear phase of relaxation could be prolonged by increasing the attachment rate of myosin heads (Fig. S2) or reducing the detachment rate (Fig. S3). Both modifications increased the duty ratio of myosin heads (24). Thin filament kinetics also affected the duration of the linear phase of relaxation. The phase could be prolonged by reducing the rate (aoff, Eq. 1) at which unoccupied binding sites switched to the unavailable state (Fig. S4) and also by increasing positive cooperativity (kplus, Eq. 1) (simulations shown in Fig. S5). The cooperative effect allowed bound myosin heads to recruit additional binding sites to the available state (9). Increasing the rate at which binding sites were activated by Ca2+ (aon) did not markedly alter the time course of relaxation (Fig. S6). This is probably because changing aon did not substantially alter the availability of binding sites when the Ca2+ concentration was low.

Fig. 4 shows that the time course of relaxation predicted by the model was modulated by mechanical perturbations. As shown in experiments using skeletal muscle fibers (25), and skeletal (26) and cardiac myofibrils (7), stretches reduced the duration of the linear phase while shortening movements prolonged relaxation. These effects reflect the strain-dependence of myosin detachment kinetics because length changes did not influence the time course of relaxation in additional simulations where g did not depend on the cross-bridge displacement (data not shown).

Additional simulations were performed to predict how the model relaxes when the Ca2+ concentration is reduced to intermediate values. As shown in Fig. S7, force did not fall with a biphasic profile when the free Ca2+ concentration was reduced by small amounts (for example, to a final concentration equal to pCa 5.0). In contrast, when the Ca2+ concentration was reduced to intermediate values (for example, pCa 5.2), force exhibited triphasic behavior. It 1) declined slowly immediately after the Ca2+ concentration was reduced, before 2) partially collapsing, and 3) finally recovering. This is a particularly interesting type of nonlinear behavior that illustrates how interfilamentary movement can perturb the dynamic coupling of cycling cross-bridges and regulated binding sites to produce complex mechanical responses (9).

All of the calculations described to this point were performed using a simple model that uses a single element to mimic the combined effects of half-sarcomere heterogeneity and series elasticity. Another factor that allows cross-bridge links to change length during isometric relaxation is the finite stiffness of the thick and thin filaments (27, 28). Fig. 5 summarizes additional calculations that were performed to test whether compliant realignment (29) of binding sites and myosin heads could influence relaxation.

Pairs of compliant actin and myosin filaments (Fig. 5 A) were simulated using techniques that have already been published (11). Because the calculations were based on stochastic techniques, the prediction for an individual trial depended on the initial mathematical conditions. These were set by a randomly generated seed. In the single trial shown in Fig. 5 B, force remained stable for ∼400 ms after the Ca2+ concentration declined before dropping abruptly as several myosin heads detached at almost the same time. Compliant myofilament systems can therefore rupture.

After model fitting, the mean force during relaxation (obtained by averaging 100 trials initiated with different seeds) matched the experimental data closely although the predicted filament extensions (∼3%) were ∼10 times larger than those measured in real experiments (for example, see Brunello et al. (30)). As in the simulations with a lumped compliance (Fig. 1 A), the transition to fast relaxation was associated with a sudden stretch of cross-bridge links (data not shown). Simulations that were performed with pairs of rigid filaments showed that force declined with a slow exponential profile (data not shown).

Discussion

These simulations demonstrate that compliance accelerates relaxation in striated muscle by allowing myosin heads to move relative to binding sites on actin. When Ca2+ declines, the number of available binding sites falls as the actin filament deactivates. Myosin heads that detach from the thin filament are therefore less likely to be able to reattach. The force in series with the molecular motors thus has to be sustained by a smaller number of myosin heads. This stretches the remaining cross-bridge links and (assuming the myosin detachment rate increases with strain) causes them to unbind more quickly. Compliant muscles therefore transition to fast relaxation because the initial reduction in Ca2+ sets up a positive feedback loop that ends in eventual mechanical rupture.

This mechanism also explains why force in the compliant system remains relatively stable immediately after the Ca2+ concentration is reduced. Although the total number of bound cross-bridges starts to fall as soon as the filaments deactivate (Fig. 1), every myosin head that remains bound elongates as the half-sarcomere reextends toward its initial length (Fig. 3 B). The increased strain in each bound head largely compensates for the declining number of bound cross-bridges until the system ruptures due to strain-sensitive cross-bridge detachment. In contrast, when the system is rigid, cross-bridge strain remains constant and force declines in proportion to the number of bound heads once the intracellular Ca2+ concentration falls (Fig. 3 D).

The simulations presented in this work thus reinforce, and provide a potential quantitative explanation for, experimental data previously published by Brunello et al. (30), These authors analyzed biphasic relaxation in single frog muscle fibers by combining sophisticated mechanical experiments with x-ray diffraction techniques. Their results showed that the number of bound cross-bridges dropped more quickly than force during the linear phase of relaxation. As a result, the mean strain of each bound cross-bridge increased until the onset of rapid relaxation. These experimental findings are compatible with the current simulations (Fig. 3).

Although this work did not focus on potential differences between relaxation in skeletal and cardiac preparations, it is likely that qualitatively similar mechanisms operate in both types of muscle. This model is sufficiently general that it probably applies equally well to skeletal and cardiac myofibrils. Differences in relaxation in distinct types of preparation probably reflect changes in the kinetic properties of myosin molecules and thin filament regulatory processes. Figs. S2–S6 show how adjusting some of these parameters alters the predicted time course of relaxation.

Model assumptions

It is interesting that the simulations illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 reproduce most aspects of the experimental data because the calculations incorporate two major assumptions that might have confounded the predictions. First, the calculations completely neglect the 3D architecture of the myofilament lattice and only consider forces that are acting directly along the thick and thin filaments. While this is the same assumption that A. F. Huxley made in his 1957 model (31), it overlooks geometrical effects that influence the probability of myosin heads being able to reach binding sites that are activated. This could be a significant oversimplification in relaxing muscle because alignment effects are more likely to be significant when most binding sites on actin are unavailable for cross-bridges to bind to (32). Including these effects in future calculations might allow the simulations to reproduce the exponential phase of relaxation with a smaller amount of viscous damping. It is also possible that radial deformations within the 3D filament lattice influence contractile function. However, these effects are very difficult to measure and/or simulate and are still the subject of active research (for example, see Williams et al. (33)).

The second major assumption is that a single series spring can mimic the combined effects of properties including, but probably not limited to, half-sarcomere heterogeneity, filament compliance, and compliance in tendons and/or other connections to the experimental apparatus. This is obviously simplistic and the assumption has drawbacks. For example, the present calculations do not provide insights into the relationship between half-sarcomere heterogeneity and relaxation time (7). This is a limitation of these simulations because there is very strong evidence that half-sarcomere heterogeneity is an important subcellular factor that influences relaxation. Specifically, it is very clear that the fast phase of relaxation is associated with sequential relengthening of individual half-sarcomeres (5).

On the other hand, the simplicity of this approach means that the technique can be readily incorporated into larger frameworks. It will be interesting to extend this work to test, for example, whether finite element models of hearts and/or skeletal muscles that include strain-dependent cross-bridge detachment exhibit more realistic behavior during relaxation than conventional finite element systems (for example, Wenk et al. (34) and Blemker and Delp (35)).

Relative importance of filament compliance

The simulations shown in Fig. 5 demonstrate that a mechanism based on compliant realignment (29) of actin binding sites and myosin heads can accelerate relaxation. However, the best fit to the experimental data was obtained in simulations where the thick and thin filaments stretched by ∼2 and ∼3%, respectively. These extensions are roughly 10 times larger than those measured in whole muscles (27, 28) and in single frog muscle fibers (30) using x-ray diffraction.

Additional simulations of filaments that stretched by only ∼0.3% (comparable to the extensions measured in real experiments) exhibited subtle biphasic relaxation. However, the transition between the slow and fast phases of relaxation was not as marked as that normally measured in experiments performed using single myofibrils.

While these results suggest that filament compliance is not a major factor in biphasic relaxation, it is possible that the model of distributed compliance (Fig. 5 A) oversimplifies features (such as the 3D architecture of the myofibrils) that are important for relaxation. On balance, the author therefore favors a conservative interpretation; filament compliance may contribute to biphasic relaxation in real muscle but it is not the most important factor driving the behavior.

Energetic efficiency

Myosin heads hydrolyze ATP each time they go through a complete kinetic cycle. It is therefore useful for myosin molecules to have a slow cycling rate during active contraction. This reduces the energy cost of force generation and allows them to absorb energy and act as brakes during eccentric contractions (36).

A potential downside of slow myosin cycling is that it may impair relaxation. As Huxley and Simmons (4) pointed out, myosin heads that remain in fixed positions relative to actin probably detach at the same rate when the muscle is fully activated as they do during relaxation. This would make it difficult for muscles to drive quick movements (including those required for locomotion and cardiac ejection) without hydrolyzing large quantities of ATP. Compliance potentially overcomes this limitation by allowing relative movement of the thick and thin filaments to shear cross-bridge links through strain-dependent cross-bridge detachment.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues at the University of Kentucky for discussions and suggestions and a reviewer for suggesting the simulations shown in Fig. S7.

The author acknowledges support from National Institutes of Health grant No. HL090749, American Heart Association grant No. GRNT25460003 to K.S.C., National Institutes of Health grant No. TR000117, and National Science Foundation grant No. 1538754.

Editor: James Sellers.

Footnotes

Seven figures and two tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(15)04767-0.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Hartree W., Hill A.V. The nature of the isometric twitch. J. Physiol. 1921;55:389–411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1921.sp001984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biesiadecki B.J., Davis J.P., Janssen P.M. Tri-modal regulation of cardiac muscle relaxation; intracellular calcium decline, thin filament deactivation, and cross-bridge cycling kinetics. Biophys. Rev. 2014;6:273–289. doi: 10.1007/s12551-014-0143-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little S.C., Biesiadecki B.J., Davis J.P. The rates of Ca2+ dissociation and cross-bridge detachment from ventricular myofibrils as reported by a fluorescent cardiac troponin C. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:27930–27940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.337295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huxley A.F., Simmons R.M. Rapid ‘give’ and the tension ‘shoulder’ in the relaxation of frog muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1970;210:32–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telley I.A., Denoth J., Stehle R. Half-sarcomere dynamics in myofibrils during activation and relaxation studied by tracking fluorescent markers. Biophys. J. 2006;90:514–530. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stehle R., Solzin J., Poggesi C. Insights into the kinetics of Ca2+-regulated contraction and relaxation from myofibril studies. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:337–357. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stehle R., Solzin J., Pfitzer G. Mechanical properties of sarcomeres during cardiac myofibrillar relaxation: stretch-induced cross-bridge detachment contributes to early diastolic filling. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2006;27:423–434. doi: 10.1007/s10974-006-9072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piroddi N., Belus A., Poggesi C. Tension generation and relaxation in single myofibrils from human atrial and ventricular myocardium. Pflugers Arch. 2007;454:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell K.S. Dynamic coupling of regulated binding sites and cycling myosin heads in striated muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014;143:387–399. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Press W.H., Teukolsky S.A., Flannery B.P. Numerical Recipes: the Art of Scientific Computing. 3rd Ed. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2007. Newton-Raphson method for nonlinear systems of equations; pp. 473–486. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell K.S. Filament compliance effects can explain tension overshoots during force development. Biophys. J. 2006;91:4102–4109. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagarias J.C., Reeds J.A., Wright P.E. Convergence properties of the Nelder-Mead simplex in method in low dimensions. SIAM J. Optim. 1998;9:112–147. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell K.S. Interactions between connected half-sarcomeres produce emergent behavior in a mathematical model of muscle. PLoS Computat. Biol. 2009;5:e1000560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell K.S., Moss R.L. History-dependent mechanical properties of permeabilized rat soleus muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 2002;82:929–943. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanner B.C., Daniel T.L., Regnier M. Filament compliance influences cooperative activation of thin filaments and the dynamics of force production in skeletal muscle. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith D.A., Geeves M.A., Mijailovich S.M. Towards a unified theory of muscle contraction. I. Foundations. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2008;36:1624–1640. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linari M., Caremani M., Lombardi V. Stiffness and fraction of Myosin motors responsible for active force in permeabilized muscle fibers from rabbit psoas. Biophys. J. 2007;92:2476–2490. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edman K.A., Reggiani C. Redistribution of sarcomere length during isometric contraction of frog muscle fibres and its relation to tension creep. J. Physiol. 1984;351:169–198. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rassier D.E., Pavlov I. Contractile characteristics of sarcomeres arranged in series or mechanically isolated from myofibrils. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;682:123–140. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6366-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford L.E., Huxley A.F., Simmons R.M. Tension responses to sudden length change in stimulated frog muscle fibres near slack length. J. Physiol. 1977;269:441–515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill A.V. The series elastic component of muscle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1950;137:273–280. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1950.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexander R.M., Bennet-Clark H.C. Storage of elastic strain energy in muscle and other tissues. Nature. 1977;265:114–117. doi: 10.1038/265114a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julian F.J., Morgan D.L. Intersarcomere dynamics during fixed-end tetanic contractions of frog muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1979;293:365–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard J. Molecular motors: structural adaptations to cellular functions. Nature. 1997;389:561–567. doi: 10.1038/39247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lombardi V., Piazzesi G., Goldman Y.E. Following tetanic stimulation, relaxation is accelerated by quick stretches of frog single muscle fibers. J. Physiol. 1990;426:38. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tesi C., Piroddi N., Poggesi C. Relaxation kinetics following sudden Ca2+ reduction in single myofibrils from skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2142–2151. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73974-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huxley H.E., Stewart A., Irving T. X-ray diffraction measurements of the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments in contracting muscle. Biophys. J. 1994;67:2411–2421. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakabayashi K., Sugimoto Y., Amemiya Y. X-ray diffraction evidence for the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments during muscle contraction. Biophys. J. 1994;67:2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80729-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daniel T.L., Trimble A.C., Chase P.B. Compliant realignment of binding sites in muscle: transient behavior and mechanical tuning. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1611–1621. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(98)77875-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunello E., Fusi L., Irving M. Structural changes in myosin motors and filaments during relaxation of skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2009;587:4509–4521. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.176222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huxley A.F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell K.S., Lakie M. A cross-bridge mechanism can explain the thixotropic short-range elastic component of relaxed frog skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 1998;510:941–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.941bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams C.D., Regnier M., Daniel T.L. Elastic energy storage and radial forces in the myofilament lattice depend on sarcomere length. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenk J.F., Ge L., Guccione J.M. A coupled biventricular finite element and lumped-parameter circulatory system model of heart failure. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2013;16:807–818. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2011.641121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blemker S.S., Delp S.L. Rectus femoris and vastus intermedius fiber excursions predicted by three-dimensional muscle models. J. Biomech. 2006;39:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunello E., Reconditi M., Lombardi V. Skeletal muscle resists stretch by rapid binding of the second motor domain of myosin to actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20114–20119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707626104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.