Abstract

Background

Box trainer systems have been developed that include advanced skills such as suturing. There is still a need for a portable, cheap training and testing system for basic laparoscopic techniques that can be used across different specialties before performing supervised surgery on patients. The aim of this study was to establish validity evidence for the Training and Assessment of Basic Laparoscopic Techniques (TABLT) test, a tablet‐based training system.

Methods

Laparoscopic surgeons and trainees were recruited from departments of general surgery, gynaecology and urology. Participants included novice, intermediate and experienced surgeons. All participants performed the TABLT test. Performance scores were calculated based on time taken and errors made. Evidence of validity was explored using a contemporary framework of validity.

Results

Some 60 individuals participated. The TABLT was shown to be reliable, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0·99 (P < 0·001). ANOVA showed a difference between the groups with different level of experience (P < 0·001). The Bonferroni correction was used to confirm this finding. A Pearson's r value of 0·73 (P < 0·001) signified a good positive correlation between the level of laparoscopic experience and performance score. A reasonable pass–fail standard was established using contrasting groups methods.

Conclusion

TABLT can be used for the assessment of basic laparoscopic skills and can help novice surgical trainees in different specialties gain basic laparoscopic competencies.

Short abstract

Simple, cheap and valid

Introduction

Minimally invasive techniques, and laparoscopy in particular, have become widespread in present clinical practice1. Training is required to reach competency in laparoscopic skills and, because the level of surgical skill is related directly to the outcome of operation, recent research has highlighted the importance of competence2. Laparoscopic surgery requires specific psychomotor skills as depth perception is missing, instruments are fixed at skin level and there is a limited range of movement3. To overcome this, laparoscopic techniques can be trained on box or virtual reality trainers outside the operating theatre. Training surgical skills using a simulator can shorten operating times, increase operative skills, and reduce the risk of both intraoperative and postoperative complications4, 5, 6, 7.

Criterion‐based assessment and training has gained ground, and it is generally accepted that trainees should train to reach a predefined level of proficiency8, 9. Assessment of skills ensures a relevant level of competency has been reached, and increases the motivation for trainees to practise8, 10. This level of competency, however, should be assessed using a test supported by evidence of validity11, 12, 13, 14. Until now, training systems for laparoscopy have been developed independently for each specialty (general surgery, urology and gynaecology), including learning advanced skills such as suturing. The Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) is the most widespread of these training systems, and is used for credentialing surgeons during specialty training15. However, there is still a need for a skills training and assessment tool for novice laparoscopic surgeons to use before performing supervised surgery on patients8.

The aims of this study were to explore evidence of validity for a test of basic laparoscopy skills, and to establish a reasonable pass–fail standard.

Methods

The study was submitted for evaluation to the regional ethics committee, which determined that no approval was needed (H‐3‐2013‐FSP66).

Training and Assessment of Basic Laparoscopic Techniques

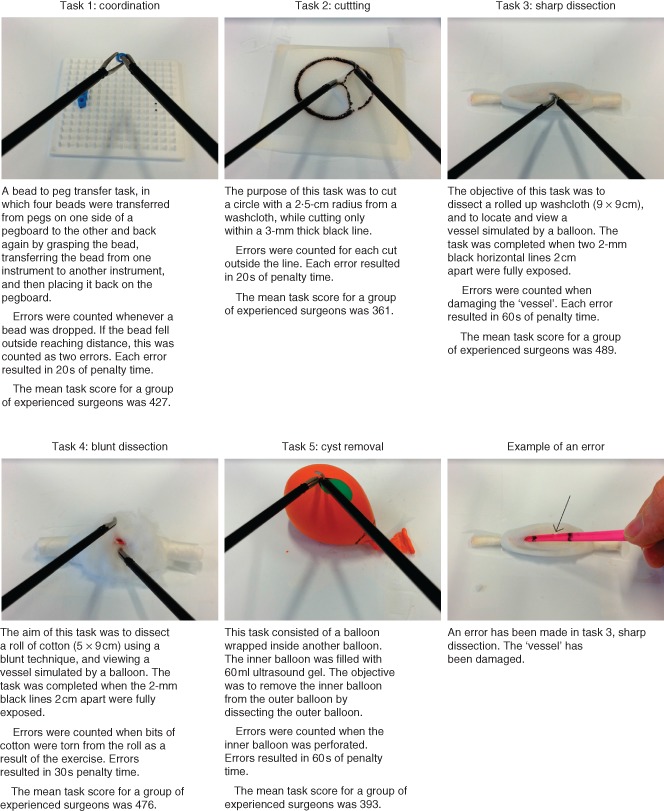

The Training and Assessment of Basic Laparoscopic Techniques (TABLT) test was developed during separate laparoscopy training programmes for general surgeons and gynaecologists. The tasks were developed with a focus on appropriate functional task alignment in order to enhance the transfer of learning16. Faculty and course participants provided feedback and adjustments were made to ensure relevance of the tasks. A pilot study was performed with two experienced surgeons and eight novices to ensure a reasonable level of difficulty and adjust the scoring system. Five tasks were included in the TABLT test, with its content reflecting basic laparoscopic techniques (Fig. 1). The tasks covered appropriate handling of laparoscopic instruments, cutting, blunt dissection and sharp dissection. The test also considered hand–eye coordination, guiding instruments via a screen, ambidexterity, accommodating the fulcrum effect and economy of movement.

Figure 1.

Description of tasks and errors

Based on elements used in the FLS training ratings system17, a scoring system was developed taking account of time and number of errors (Fig. 1). For each task, a score was calculated by subtracting the time spent on the task and a task‐specific penalty score from a maximum time of 600 s, using the formula: task score = 600 − completion time − (no. of errors × penalty time per error).

The task scores were then standardized by dividing the task score by the mean score from a group of experienced surgeons and then multiplying it by 100. A performance score for the whole test was calculated as the sum of the five standardized task scores. The scoring system was tested during the pilot study.

Establishing validity evidence

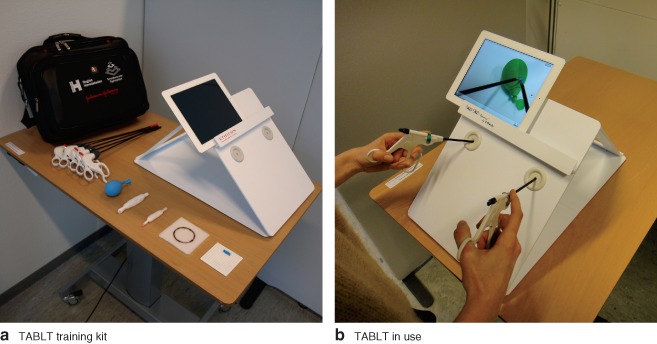

A cohort of laparoscopic surgeons and surgical trainees were recruited and evidence of validity established using a contemporary framework of validity14. In accordance with this framework, evidence of validity was collected from five sources: content, response process, internal structure, relation to other variables and consequences of the test. Participants were recruited from three different specialties (general surgery, gynaecology and urology). Participants were recruited by e‐mail through departmental heads, consultants responsible for training and direct contacts. They were divided into three groups according to level of laparoscopic experience. Novices had no previous experience in laparoscopic surgery, and less than 2 h of training on either a box trainer or virtual reality trainer; those with an intermediate level of experience had performed between one and 100 laparoscopic procedures; and experienced surgeons had carried out more than 100 laparoscopic procedures. Both intermediate and experienced surgeons were undertaking laparoscopic surgery in their current places of work. The TABLT test was administered on a portable tablet trainer18 (Fig. 2). Testing was performed after work or on days off, according to participant availability. All performed the TABLT test twice. The first attempt was to familiarize themselves with the set‐up and scoring system. The second attempt was used for assessment purposes; it was rated on site by the corresponding author and afterwards by a blinded assessor using a video recording. The blinded assessor was another member of the research group who practised rating using videos recorded during a pilot study. Three videos, with examples of different types of error, were used.

Figure 2.

a Training and Assessment of Basic Laparoscopic Techniques (TABLT) training kit, including tasks. b Surgical trainee using TABLT

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed to explore the internal structure. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated, with single measures and absolute agreement definition. ANOVA was used to explore relationships with other variables. Differences between groups of laparoscopic surgeons with various levels of experience were analysed. A groupwise comparison using ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was done to identify differences between groups for each of the pairings − novice versus intermediate, novice versus experienced, and intermediate versus experienced surgeons. The Pearson product–moment correlation coefficient was calculated to examine any correlation between the number of procedures performed and the test score. A Pearson's r value of 0·7 was considered an acceptable measure of correlation. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant in the aforementioned tests. The contrasting groups method was used to set the pass–fail level, and the consequence of applying this was reported using relative frequencies converted to percentages. A pass–fail score that passed at least 85 per cent of the experienced surgeons and failed at least 85 per cent of the novices was considered reasonable. SPSS® version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

All 60 laparoscopic surgeons and trainees (Table 1) completed the TABLT test twice. The second attempt was rated on site and by a blinded video assessor, resulting in 120 ratings.

Table 1.

Participants

| Novice | Intermediate | Experienced | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 60) | |

| Age (years) | 24–31 | 27–41 | 31–58 | 24–58 |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 7 : 13 | 11 : 9 | 13 : 7 | 31 : 29 |

| Specialty | ||||

| Surgery | 11 | 13 | 10 | 34 |

| Urology | 3 | 5 | 5 | 13 |

| Gynaecology | 6 | 2 | 5 | 13 |

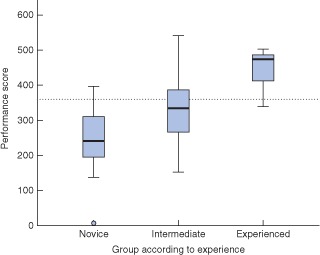

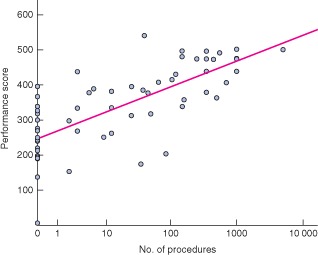

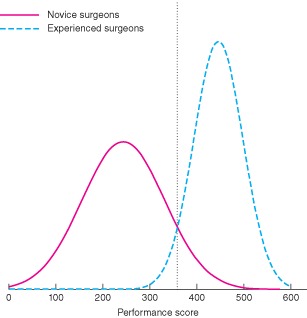

Validity evidence is summarized in Table 2. The internal structure was explored by analysing test reliability. A high level of reliability was shown, with an ICC of 0·99 (P < 0·001). Relationships with other variables, examined by analysing variation in performance scores between novice, intermediate and experienced surgeons, are shown in Fig. 3. A significant difference between these groups was found (P < 0·001). The test discriminated between novices and experienced surgeons (P < 0·001), novice and intermediate surgeons (P = 0·003), and intermediate and experienced surgeons (P < 0·001). There was a correlation between the level of laparoscopic surgical experience and the test score, with a Pearson correlation r value of 0·73 (P < 0·001) (Fig. 4). A pass–fail level was established at 358 points using the contrasting groups methods (Fig. 5). The consequence of this pass–fail level was that two of 20 novices passed the test and two of 20 experienced surgeons failed it.

Table 2.

Summary of validity evidence

| Source of validity evidence | Questions related to each source of evidence | Validity evidence for TABLT |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Does the content reflect the underlying construct? | Tasks are aligned with the construct |

| Response process | Are sources of bias reduced? | Assessment can be done blinded, and calculation of the score automated |

| Internal structure | Is the test score reliable? | A high level of reliability shown: ICC = 0·99 (P < 0·001) |

| Relation to other variables | Does the test score correlate with a known measure of competence? |

Novices, intermediates and experts score significantly differently (P ≤ 0·003, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction) Test score correlates with operative experience: Pearson correlation r = 0·73 (P < 0·001). |

| Consequences of testing | What are the consequences of the pass–fail score? | Two of 20 of experts failed and two of 20 of novices passed the test |

TABLT, Training and Assessment of Basic Laparoscopic Techniques; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

Figure 3.

Box plot of performance scores in relation to level of experience. Median values (horizontal lines), i.q.r. (boxes), and range (error bars) excluding outlier (circle) are shown. The dotted line indicates the pass–fail level. Mean(s.d.) scores for novice, intermediate and experienced surgeons were 244(88), 331(94) and 446(52) respectively

Figure 4.

Performance scores according to the level of experience expressed as number of procedures. Linear R 2 = 0·526

Figure 5.

Standard setting using contrasting groups method. The dotted line indicates the pass–fail level

Discussion

The design of TABLT was inspired by another laparoscopic training and testing model, FLS19. The tasks included in TABLT all reflected laparoscopic techniques that ensured a functional alignment of content with the construct, thereby providing evidence of validity from content. In contrast to the FLS, a laparoscopic suturing task was not included in TABLT, because this was considered a more advanced laparoscopic skill not performed by most novices. Camera navigation, on the other hand, is an essential skill and the focus of the Laparoscopic Skills Training and Testing used in gynaecology20. Camera navigation is a relevant skill to train, but requires a movable camera, which is not currently included in the TABLT test. Other test systems of laparoscopic skills focus on basic movement and coordination skills21. TABLT includes these skills, but also surgical techniques such as cutting, blunt dissection and sharp dissection. Cutting and dissection are important laparoscopic techniques to master, especially as functional task alignment is high and it can help with instrument familiarization. The TABLT tasks reflect many of the skills needed when surgical trainees perform their first supervised laparoscopic operation on a patient.

Reducing sources of bias and ensuring that the intended response was elicited when administering the test provided evidence from the response process. Bias from data entry was countered by using simple spreadsheets that were preformatted to perform automatic score calculations. This also facilitated maintenance of data integrity, as data in spreadsheets are easily accessible and automated score calculations are transparent. Participants demonstrated an appropriate response during testing because their first attempt allowed them to develop a strategy for doing the tasks, and they used this in the second attempt, which was the one used for rating.

The results showed a high ICC value, which demonstrated that the scoring system of the TABLT was reliable. A high level of reliability supports evidence of the internal structure. Simple scoring systems, relying on number of errors and time taken, have proved to be reliable in other tests such as the FLS22. The rating can be made either while the tasks are being performed or afterwards from a video recording. Using video recordings allows blinded rating, which minimizes bias from raters.

Evidence of validity was found from relationships with other variables, as there were significant differences in performance scores between the groups with different levels of experience. Correlation was seen between the level of laparoscopic experience measured by the number of procedures performed and test performance scores. Measuring laparoscopic skills by the number of procedures can be problematic owing to recall bias. However, the number of procedures performed by a surgeon has been shown to correlate well with performance level and patient outcome2. Having chosen 100 procedures as the cut‐off criterion for experienced surgeons, it seemed reasonable to assume that all experienced surgeons had a sufficient level of competency regarding basic laparoscopic skills.

The pass–fail level was established using the contrasting groups method. Two of 20 novices passed the test, whereas two of 20 experienced surgeons failed. This pass–fail level seems acceptable as it discriminates well between competent and non‐competent surgeons. As a result of this, some novices will pass the test after a short training period, and some experienced surgeons will fail. The FLS is also subject to a similar challenge; 18 per cent of competent surgeons are expected to fail the test and 18 per cent of non‐competent surgeons to pass17. When setting a pass–fail level, it is important that it should be achievable by novice trainees9. To examine this further, it will be necessary to do more research exploring performance curves of the TABLT test among novice trainees.

Evidence of validity was explored by using a contemporary framework of validity14. An essential part of this process was to consider threats to validity23. Threats to validity can be divided into two main categories: construct under‐representation and construct irrelevant variance. Construct under‐representation occurs when the content of the test does not sufficiently represent the construct. Construct irrelevant variance is a result of systematic bias. An example of a threat from construct under‐representation is low reliability. In the present study, a high ICC was found, indicating that the scoring system of the TABLT test was reliable.

Threats to validity from construct irrelevant variance include: rater‐related bias, level of difficulty of the test and unjustifiable methods for setting the pass–fail level23. The TABLT test can be rated by both direct observation and video recordings. A previous study24 showed that experienced physicians were more highly rated as the result of direct observations than they were for blinded rating. The opposite was true for novices. This type of bias did not seem to influence the TABLT test scores, as demonstrated by the high ICC value. The reason lies in the simplicity of the scoring system, which used only time taken and number of errors made. The scoring system was easy to apply and therefore reduced the risk of rater‐related bias. The variety of performance scores by novices and intermediates (Fig. 3) demonstrated that the level of difficulty of the test was appropriate. The present study also included a wide variety of experienced surgeons with different levels of experience. Using participants with many skill levels for the test is important, as wide variation in skill levels has been recognized among practising laparoscopic surgeons9.

The study included a large number of participants with a wide range of competencies across three surgical specialties. This is a strength of the study because all participants were either practising laparoscopic surgeons or training to be laparoscopic surgeons. The main limitation was the focus on the assessment aspect of the TABLT test. The training element of TABLT still needs to be investigated in more detail. In particular, the standard setting should be explored by allowing trainees to train on TABLT and examine their performance curves. The pass–fail level might be set too low, resulting in trainees reaching an insufficient level of competency. If the level were to be set too high, however, the test would not be fair, and trainees would spend time overtraining, which may not result in a higher level of skill in the operating theatre. This highlights a further limitation, as the transfer of skills from the TABLT to a clinical setting has not been explored. The scoring system, although easy to use and reliable, may be too simple to provide meaningful feedback to the trainees on their performance. Using a preformatted spreadsheet makes score calculations easy and transparent so that trainees themselves may be able to perform self‐assessment during training or receive formative feedback from faculty. To ensure that appropriate laparoscopic techniques are acquired, the TABLT scores could be supplemented by feedback or ideas for improvement from an experienced surgeon.

Training models based on FLS have been developed for each surgical specialty19, 25, 26, 27. Although developed for general surgeons, research has demonstrated the benefits of the FLS practical test in both urology and gynaecology28, 29. The TABLT test was designed to be used in cross‐specialty training. The techniques practised are used widely, making it possible for experienced laparoscopic surgeons from one specialty to supervise a trainee from a different specialty. A cross‐specialty approach also allows trainees from different specialties to practise together and learn from one another. An added benefit is that hospital departments and simulation centres can pool resources, offering more frequent courses and additional training opportunities. When trainees have mastered basic skills in laparoscopy, they can move on to specialty‐specific training, such as operation modules on a virtual reality simulator4.

TABLT was developed to be used on a portable tablet trainer18 (Fig. 2), but may be used in any box trainer. Training on a portable trainer increases the flexibility of training30. Box trainers are in general cost‐effective, and have proved to be equally as good as virtual reality trainers for training basic laparoscopic skills31. Easy access to basic testing and training in laparoscopy could benefit trainees and, more importantly, their patients.

Acknowledgements

Funding and equipment was provided by the Centre for Clinical Education, Capital Region of Denmark. The instruments used in this trial were donated to the Centre for Clinical Education by Johnson & Johnson. E.T. has received non‐restricted educational grants from Johnson & Johnson outside the submitted work.

Disclosure: The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Darzi SA, Munz Y. The impact of minimally invasive surgical techniques. Annu Rev Med 2004; 55: 223–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O'Reilly A, Oerline M, Carlin AM, Nunn AR et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1434–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Derossis AM, Fried GM, Abrahamowicz M, Sigman HH, Barkun JS, Meakins JL. Development of a model for training and evaluation of laparoscopic skills. Am J Surg 1998; 175: 482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larsen CR, Soerensen JL, Grantcharov TP, Dalsgaard T, Schouenborg L, Ottosen C et al Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009; 338: b1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grantcharov TP, Kristiansen VB, Bendix J, Bardram L, Rosenberg J, Funch‐Jensen P. Randomized clinical trial of virtual reality simulation for laparoscopic skills training. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 146–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahlberg G, Enochsson L, Gallagher AG, Hedman L, Hogman C, McClusky DA III et al Proficiency‐based virtual reality training significantly reduces the error rate for residents during their first 10 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Am J Surg 2007; 193: 797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, O'Brien MK, Bansal VK, Andersen DK et al Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double‐blinded study. Ann Surg 2002; 236: 458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reznick RK, MacRae H. Teaching surgical skills – changes in the wind. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 2664–2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gallagher AG, Ritter EM, Champion H, Higgins G, Fried MP, Moses G et al Virtual reality simulation for the operating room: proficiency‐based training as a paradigm shift in surgical skills training. Ann Surg 2005; 241: 364–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Korndorffer JR Jr, Kasten SJ, Downing SM. A call for the utilization of consensus standards in the surgical education literature. Am J Surg 2010; 199: 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Downing SM. Validity: on meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ 2003; 37: 830–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med 2006; 119: 166: e7–e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (U.S.) . Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. American Educational Research Association: Washington, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soper NJ, Fried GM. The fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery: its time has come. Bull Am Coll Surg 2008; 93: 30–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, Hatala R, Zendejas B, Cook DA. Reconsidering fidelity in simulation‐based training. Acad Med 2014; 89: 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fraser SA, Klassen DR, Feldman LS, Ghitulescu GA, Stanbridge D, Fried GM. Evaluating laparoscopic skills: setting the pass/fail score for the MISTELS system. Surg Endosc 2003; 17: 964–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bahsoun AN, Malik MM, Ahmed K, El‐Hage O, Jaye P, Dasgupta P. Tablet based simulation provides a new solution to accessing laparoscopic skills training. J Surg Educ 2013; 70: 161–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fried GM. FLS assessment of competency using simulated laparoscopic tasks. J Gastrointest Surg 2008; 12: 210–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molinas CR, De Win G, Ritter O, Keckstein J, Miserez M, Campo R. Feasibility and construct validity of a novel laparoscopic skills testing and training model. Gynecol Surg 2008; 5: 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schreuder HW, van den Berg CB, Hazebroek EJ, Verheijen RH, Schijven MP. Laparoscopic skills training using inexpensive box trainers: which exercises to choose when constructing a validated training course. BJOG 2011; 118: 1576–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vassiliou MC, Ghitulescu GA, Feldman LS, Stanbridge D, Leffondre K, Sigman HH et al The MISTELS program to measure technical skill in laparoscopic surgery: evidence for reliability. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Downing SM, Haladyna TM. Validity threats: overcoming interference with proposed interpretations of assessment data. Med Educ 2004; 38: 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Konge L, Vilmann P, Clementsen P, Annema JT, Ringsted C. Reliable and valid assessment of competence in endoscopic ultrasonography and fine‐needle aspiration for mediastinal staging of non‐small cell lung cancer. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tjiam IM, Persoon MC, Hendrikx AJ, Muijtjens AM, Witjes JA, Scherpbier AJ. Program for laparoscopic urologic skills: a newly developed and validated educational program. Urology 2012; 79: 815–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolkman W, van de Put MAJ, Woterbeek R, Trimbos JBMZ, Jansen FW. Laparoscopic skills simulator: construct validity and establishment of performance standards for residency training. Gynecol Surg 2008; 5: 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hennessey IA, Hewett P. Construct, concurrent, and content validity of the eoSim laparoscopic simulator. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2013; 23: 855–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dauster B, Steinberg AP, Vassiliou MC, Bergman S, Stanbridge DD, Feldman LS et al Validity of the MISTELS simulator for laparoscopy training in urology. J Endourol 2005; 19: 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zheng B, Hur HC, Johnson S, Swanström LL. Validity of using Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (FLS) program to assess laparoscopic competence for gynecologists. Surg Endosc 2010; 24: 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Korndorffer JR Jr, Bellows CF, Tekian A, Harris IB, Downing SM. Effective home laparoscopic simulation training: a preliminary evaluation of an improved training paradigm. Am J Surg 2012; 203: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zendejas B, Brydges R, Hamstra SJ, Cook DA. State of the evidence on simulation‐based training for laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 586–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]