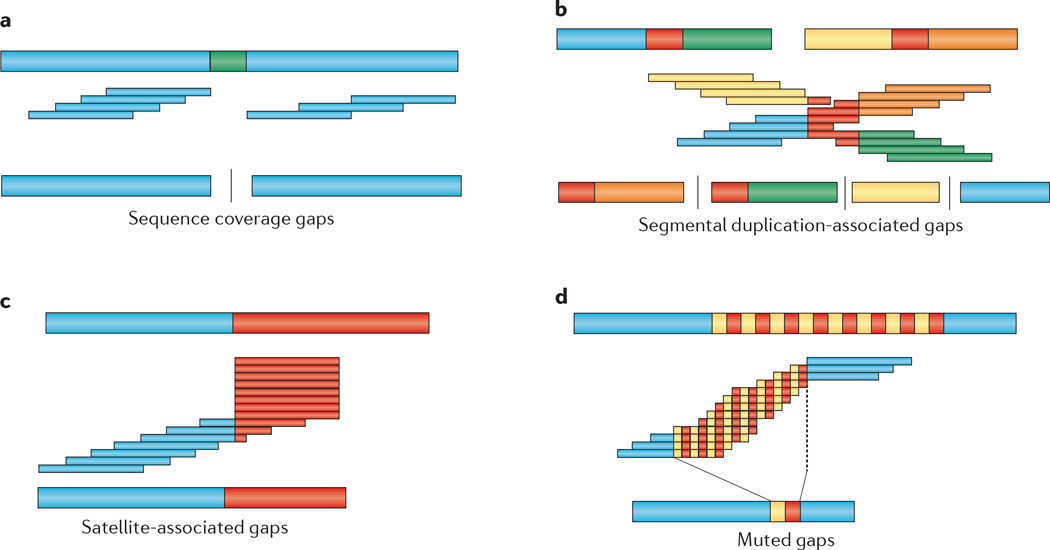

Figure 1. Types of genome assembly gaps.

Abstracted images of genome assemblies are illustrated. The genome architecture being resolved is shown at the top of each figure part as thick bars. Repetitive sequences are shown in red. Read overlaps are illustrated below the genome as thin bars (middle of each figure part), with regions overlapping repeats filled as red. The resulting assembly contigs are shown below (bottom of each figure part). Gaps are shown as vertical bars separating contigs to indicate unresolved sequences. a | The absence or reduction in sequence reads due to potential amplification or sequencing biases creates ‘dropouts’, where the assembled sequence is incomplete. b | Large segmental duplications of high sequence identity (orange and green) make read overlaps ambiguous, leading to multiple gaps flanking segmental duplications. The effect becomes exacerbated if the duplications are structurally polymorphic in a diploid genome. Long-range sequence information is required to resolve the complete sequence. c | Satellite-associated gaps are a special case leading to read ‘pileups’ due to higher-order tandem arrays of repetitive sequence, and they cannot be resolved using paired-end sequence information. These occur primarily in centromeric, acrocentric and telomeric areas of genomes. d | Muted gaps arise when the assembly is contracted relative to the true genome when overlaps are consistent with a smaller representation of the genome. These are often associated with repetitive sequences that cannot be easily amplified and/or are incompatible with cloning and propagation (that is, when they are toxic to Escherichia coli), such as simple tandem repeats.