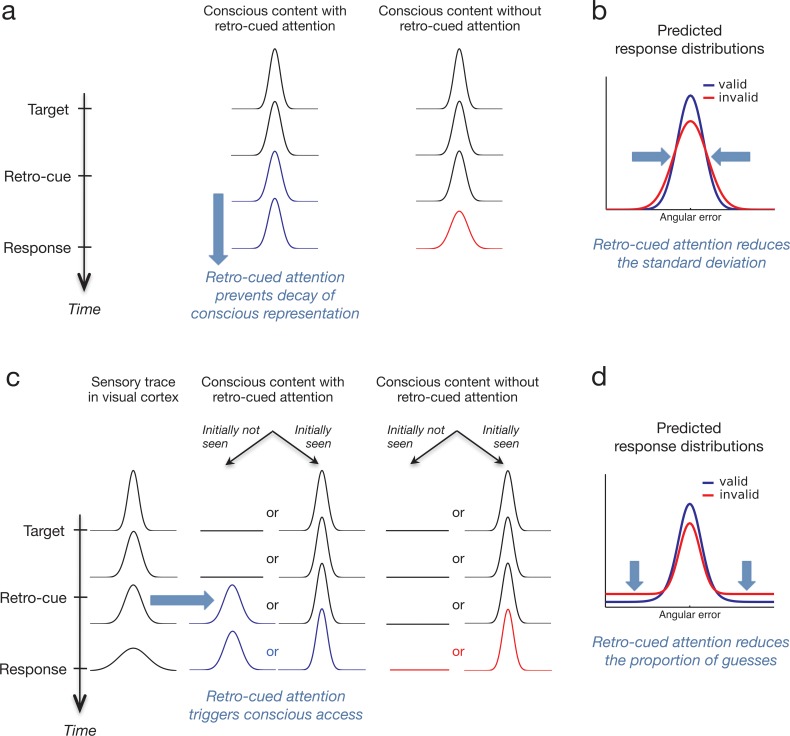

Fig 2. Hypotheses and predictions.

According to a first hypothesis (a) retro-cued attention prevents the decay of an existing conscious percept. In this proposition, even when the target is conscious, in the absence of retro-cued attention the precision of this conscious representation decays slightly with time (right column). When retro-cued attention is focused on the target’s location (left column), it would prevent this slight decay of the conscious representation. This hypothesis thus predicts that the precision of the response on target’s orientation should be increased for valid retro-cues (blue curve) compared to no cues or invalid retro-cues (red curve) (b). The alternative hypothesis (c) is that retro-cued attention triggers conscious perception on trials where the target would otherwise have been missed. In this proposition, the target is not always consciously accessed, and thus not always consciously seen following its presentation (right column), but it always leaves a sensory trace in the visual cortex (left column). On trials were the target initially failed to reach conscious access, retro-cued attention at the target’s location could still promote the remaining sensory trace in visual cortex at this location to be consciously accessed (middle column). This hypothesis predicts that valid retro-cues (blue curve) should decrease the number of guesses compared to no cues or invalid retro-cues (red curve) (d). It also predicts a decrease in the precision of the accessed information: indeed valid retro-cues trigger conscious access to a degraded sensory trace on trials that otherwise would have counted as guess. Thus, less precise representations get included in the standard deviation estimate.