Abstract

Objective

The Family-to-Family Education Program (FTF) is a 12-week course for family members of adults with mental illness offered by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). This study evaluates the effectiveness of FTF.

Method

A total of 318 consenting participants in five Maryland counties were randomly assigned to take FTF immediately or to wait at least three months for the next available class with free use of any other NAMI, community or professional supports. Participants were interviewed at study enrollment and 3 months later (at course termination) regarding problem and emotion-focused coping, subjective illness burden, and distress. We used a linear mixed effects multilevel regression model to test for significant changes over time between intervention conditions.

Results

FTF participants had significantly greater improvements in problem-focused coping as measured by empowerment and illness knowledge. Exploratory analyses revealed FTF participants had significantly enhanced emotion-focused coping as measured by increased acceptance, reduced distress, and improved problem solving. Subjective illness burden did not differ between groups.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that FTF is effective for enhancing coping and empowerment of families of persons with mental illness, though not for reducing subjective burden. Other benefits for problem solving and reducing distress are suggested, but require replication.

Introduction

Family members play important roles in the lives of adults with serious mental illnesses (SMI)(1), and often seek information and support regarding treatments, relevant resources, coping, communication and problem solving skills (2–6). While virtually all reviews recommend including families in the care of persons with mental illness (7), reported rates rarely exceed 50% (8–10). Families often report dissatisfaction regarding their interactions with the mental health system (4, 11–16).

The self-help movement has offered a partial remedy to unmet family needs by offering programs delivered by and for family members of individuals with mental illness. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) sponsors the most widely disseminated such program, the NAMI Family-to-Family Education Program (FTF). FTF is a 12-week class with a highly-structured standardized curriculum, developed and conducted by trained family members. In weekly 2–3 hour sessions, family–member attendees receive information about mental illnesses, medication, and rehabilitation. They also learn self-care, mutual assistance and communication skills, problem-solving strategies, advocacy, and develop emotional insight into their responses to mental illness (17).

While extensive research has examined the effectiveness of family education administered by clinicians, research on family self-help programs has been limited (7). Pickett-Schenk and colleagues compared families receiving the Journey of Hope, an 8-week family-led education course, with a wait-list control group. Families involved in the course reported higher levels of knowledge about schizophrenia, improved information needs, lower levels of depression, improved family relationships, and improved satisfaction in their caregiver role (18–20). However, Journey of Hope was restricted to Louisiana and is not currently available. Two previous studies suggested that FTF reduces participants’ subjective burden and increases their perceived empowerment. The first was an uncontrolled trial and in the second participants served as their own controls during a waiting list period. (21–22) The present study tested the effectiveness of FTF with a randomized controlled design. We hypothesized that FTF would produce increased empowerment, knowledge and reduced subjective burden as well as improved emotion-focused coping and family functioning with reduced distress.

Methods

Settings and Design

Individuals were randomly assigned to take the FTF class immediately or to the control condition in which individuals waited at least three months until the next FTF class. Controls could use any other NAMI, professional or community supports. The study was conducted in the regions of Maryland served by five NAMI affiliates: Baltimore Metropolitan region, and Howard, Frederick, Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties. FTF classes were delivered by usual NAMI-affiliate family-member trained volunteers, using usual locations and schedules; the study did not alter the FTF classes or its delivery. Anyone contacting the state NAMI-MD office or a participating affiliate and interested in FTF received basic information and was referred to the NAMI-MD’s FTF state coordinator. She spoke with each person to determine if they were appropriate to participate in the FTF program and if so, to describe this study, conduct a preliminary screen for eligibility and determine willingness to consider study participation. Research assistants contacted eligible willing family members and obtained informed consent via telephone in a protocol approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board. Consenting participants were assessed at baseline (before FTF started), randomized, and interviewed again three months later (after FTF) by a research assistant blinded to their study condition, using a structured telephone interview lasting approximately 60 minutes. A stratified block randomization procedure was used with stratification by site and randomly varying block sizes. After the baseline interview an independent member of the research staff informed the research assistant of the treatment assignment which was kept in sealed envelopes; the research assistant then informed participants of their assigned condition. Participants were told at the beginning of each follow-up interview not to reveal their study condition; if that occurred, the interview would be stopped and continued with another interviewer. Participants were recruited between 3/15/2006 and 9/23/2009 and enrolled in 54 different classes. They were paid $15 for each interview. At the conclusion of the second interview, the interviewer inquired about the number of FTF classes attended and the participant’s use of other supports during the three month interval.

Participants

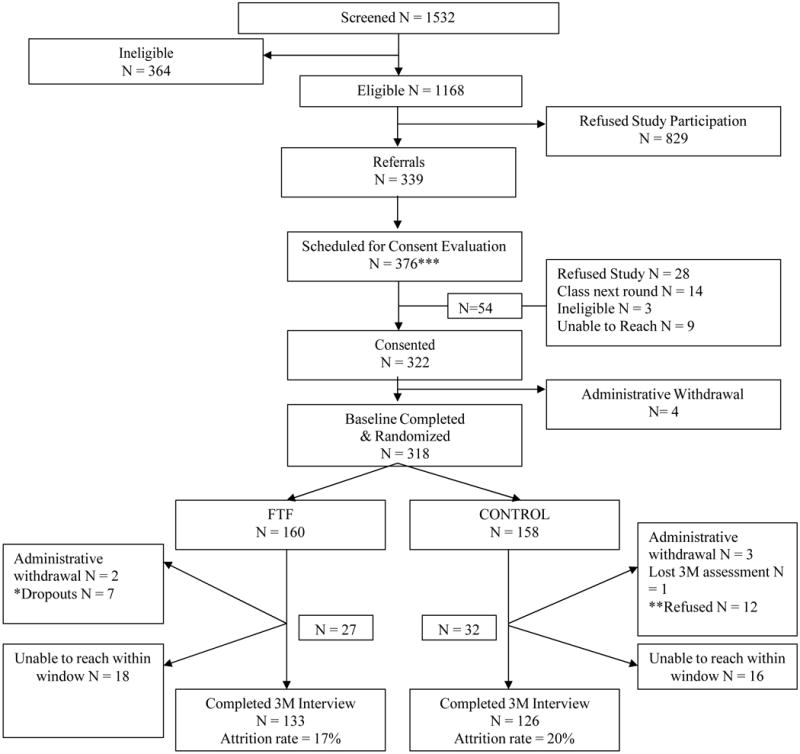

Individuals were eligible for the study if they were 21 to 80 years of age, desired enrollment in the next FTF class regarding a member of the family or significant other, and spoke English. As illustrated in Figure 1, 1532 individuals were screened of whom 1168 were eligible. The most common reason for ineligibility was that a person’s schedule did not permit participation in FTF at the next round of class offerings. Of those who were eligible, 339 (30%) were willing to consider study participation. The most common reason for declining study participation was unwillingness to take the chance of needing to wait before taking FTF. A total of 37 additional people who were family members of potential participants were also eligible and expressed interest in the study. From this group, 322 individuals consented to the study but 4 were administratively withdrawn, leaving a total of 318 consented individuals who completed the baseline interview and were randomized, 160 to FTF, and 158 to control.

Figure 1. FTF Family Member Flow Chart.

*Participant ended his/her participation in the study

**Participant refused to complete the follow up interview

***37 family members referred to the study a second member of their family who was also planning to take the FTF class and agreed to consider being part of the study. With respect to family member “doubles,” there were 10 pre-existing doubles in the N=339, and then 37 more were referred; the N=376 group thus included 47 “doubles.” Four people from the “double”family were dropped because they never consented. In the N=318 Baseline completed and randomized sample, there were 43 doubles. One person in control group from the double family was administratively withdrawn, so the final sample had 42 doubles; the completers only sample included 32 within family pairs.

Compared to individuals who refused study participation, consenting individuals were younger (51.9 ±10.9 vs. 53.5 ±11.6 years, t = −2.13, df = 1063. p = .034) and more likely to be women [241/313 (77%) vs. 601/849 (71%), χ2 = 4.53, df=1, p = .033]. Consenting and refusing individuals did not differ by county or race. A total of 133 (83%) and 126 (80%) individuals in the FTF and control conditions, respectively, completed three-month follow-up interviews.

Assessments and Variables

We obtained background information using the Family Experience Interview Survey (FEIS)(23). This scale elicits information regarding demographics and level of involvement with participant’s ill relative, the ill relative’s demographics and mental health history, extent of contact between the participant and the ill family relative and the extent to which family members provide assistance in daily living and supervision to their ill relative.

Indicators of problem-focused coping were evaluated with empowerment and knowledge scales. The Family Empowerment Scale has three subscales: family (12 items), community (10 items) and service system empowerment (12 items) (24). We assessed knowledge about mental illness using a 20-item true/false test of factual information (available from authors) covering material drawn from the FTF curriculum that tapped general knowledge about mental illnesses.

Emotion-focused coping was measured with the four-item COPE subscales that measure four dimensions: seeking social support, positive reinterpretation and growth, acceptance, and denial (25). The COPE has demonstrated good reliability and validity and has been adapted for family members of individuals with SMI (26).

Subjective illness burden was evaluated with the FEIS worry and displeasure scales (23). The 8-item worry subscale asks respondents to rate their level of concern on different aspects of their ill relative’s life. The 8-item displeasure subscale measures the participants’ emotional distress around their ill relative’s situation (23).

We assessed distress with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The BSI-18 is a measure of psychological distress designed for use primarily in non-clinical, community populations. It measures level of somatization, anxiety, and depression, and generates a total score of the respondent’s overall level of psychological distress. The raw scores for the BSI symptom dimensions were converted to area T-scores based on the community male and community female norm tables. The BSI-18 has well-established reliability and validity (27). The CES-D Modified is a reliable and valid 14-item scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in the general population (28, 29).

We assessed family functioning with the Family Assessment Device (FAD) and the Family Problem-Solving Communication Scale (FPSC). The FAD evaluates family functioning and family relations (30) and is widely used in studies of family response to medical and physical illness, with well-established reliability and validity (31). We used its general functioning (12 items) and problem-solving (5 items) subscales. The ten-item FPSC measures positive and negative aspects of communication (32).

We adapted a series of structured questions regarding the use of diverse community and clinical family support services, support groups, and attendance at FTF classes from our previous studies.

Fidelity

To ensure that participants received the standardized FTF program, experienced FTF teachers acted as observers to rate one session of each course. They were oriented to the purpose and procedures of the fidelity observations, and were paid $40 for each completed observation. We randomly sampled one of the first 8 class meetings from each 12-session course. Classes 1 and 3 were excluded due to the sensitive nature of their content. Fidelity ratings were based on a structured rating form created for a prior FTF study (available from authors) in consultation with Dr Joyce Burland (FTF creator) to capture 18 essential elements of FTF. Overall scores were calculated by deriving the percentage of indicators present. If a class meeting scored less than 75% fidelity, we randomly sampled and assessed another class meeting in that same course from among classes 9, 10 or 11 (class 12 was excluded due to its celebratory nature). Ten different observers provided 49 observations. The average fidelity rating was 90% (SD=7.54). Only one class fell below 75% and the second class assessment met fidelity standards.

Data Analysis Plan

We first assessed the impact of loss to follow up using t-tests and chi-square tests to assess whether participants who completed the three month assessment differed from those who did not on demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, education, income, relationship to consumer) and baseline scores of outcome variables (coping, subjective burden, psychological distress and family functioning).

We used multilevel regression models (SAS Proc Mixed) to test our main hypotheses of whether participation in FTF produced increased constructive coping activities, reduced subjective illness burden, reduced distress, and improved family functioning. The models tested for significant changes over time (baseline, 3 months) between conditions (FTF, control) by using the score at the 3 month assessment as the dependent variable and condition as the primary independent variable with baseline assessment score and class as covariates.

Class was included in the model as a random variable because participants taking the same class may be more similar in their response to the intervention than people from different classes. Since people in the same class (FTF condition) were likely to be more similar to each other than the control participants, we estimated this effect separately for each condition.

Another way that participants can be similar is that they might be related. Relatives who were in the study were always randomized to the same condition. Since the family pairings were nested within classes, the variance component due to class incorporated the variance due to family. Because of the small class cluster size (4.32± 2.94), we did not attempt to fit a separate variance component due to family. To control for Type I error for our primary hypotheses (problem-focused coping reflected by empowerment and knowledge and subjective burden) we used the sequential Bonferonni-type procedure for dependent hypothesis tests of Benjamini and Yekutieli (2001) to control the false discovery rate at 5% (33). The false discovery rate is the expected (or on average) proportion of falsely rejected hypotheses. Our primary hypotheses were informed by our preliminary data. Exploratory hypotheses tested dimensions not previously examined. No error correction was used for the exploratory hypotheses of emotion focused coping, distress and family functioning.

Two additional sets of analyses were completed. First we repeated the identical analyses described above but only including those participants in the FTF condition who attended at least one class. Although our primary results are based on the intent to treat analysis including all randomized subjects who completed the three month assessment, we also wanted to examine an FTF sample that had some FTF exposure. This excluded 17 FTF participants who did not attend any classes.

Second, in order to address potential bias due to participant loss to follow-up, we re-fit the models after using a regression multiple imputation procedure to impute missing 3-month outcome values using the guidelines in Sterne et al. (2009)(34). Predictors for the imputation model for each outcome included the following variables: class, condition, outcome variable assessed at baseline, baseline variables predictive of loss to follow-up, and other measures correlated with the outcome measure at baseline. Thirty imputed datasets were generated and analyzed for each outcome using SAS Proc MI. Results of the analysis of each of the thirty datasets were combined using SAS Proc MIAnalyze. These analyses did not substantively change our findings.

Results

Participants

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the sample of individuals who completed both assessments. Family members who were Caucasian (p<.001), and who had income more than $50,000 per year (p < .001), lower baseline worry (p=.012), higher baseline knowledge (p=.002), higher levels of acceptance (p=.045) and lower levels of somatization (p=.042) were somewhat more likely to be interviewed at follow up. The characteristics of participants lost to follow up were not different by study condition.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Completer Sample (N=259) |

FTF (N=133) |

Control (N=126) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | n/Mean | % | n/Mean | % | n/Mean | % |

| Age (Yr) | 52.2 ± 10.6 | 52.6 ± 10.2 | 51.8 ± 11.0 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 60 | 23 | 33 | 25 | 27 | 22 |

| Female | 196 | 77 | 99 | 75 | 97 | 78 |

| Race | ||||||

| Asian | 6 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 55 | 21 | 29 | 22 | 26 | 21 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| White | 186 | 72 | 92 | 70 | 94 | 75 |

| Other | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less Than HS Graduate | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| High School Graduate | 28 | 11 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Some College | 54 | 21 | 27 | 20 | 27 | 21 |

| College Graduate | 70 | 27 | 34 | 26 | 36 | 27 |

| Post Graduate | 101 | 39 | 53 | 40 | 48 | 38 |

| Family Income | ||||||

| $50000 Or Less | 67 | 30 | 34 | 26 | 33 | 28 |

| >$50000 | 185 | 73 | 98 | 74 | 87 | 73 |

| Relationship To Consumer | ||||||

| Parent | 154 | 60 | 75 | 56 | 79 | 63 |

| Chid | 19 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 10 |

| Sibling | 32 | 12 | 20 | 15 | 12 | 10 |

| Spouse/Partner | 27 | 10 | 18 | 14 | 9 | 7 |

| Other Kin | 25 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 10 |

| Non-kin/Friend | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Affiliate Location | ||||||

| Baltimore Metro | 88 | 34 | 46 | 35 | 42 | 33 |

| Montgomery County | 86 | 33 | 41 | 31 | 45 | 36 |

| Frederick Country | 39 | 15 | 22 | 17 | 17 | 14 |

| Howard County | 43 | 17 | 21 | 16 | 22 | 18 |

| Prince George’s County | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | .0 |

| Objective Illness Burden | ||||||

| Assistance In Daily Living | 0.27 ± 0.24 | 0.26 ± 0.23 | 0.28 ± 0.25 | |||

| Supervision | 0.11 ± 0.14 | 0.12 ± 0.15 | 0.09 ± 0.14 | |||

| Consumer Hospitalized in the Past Six Months | 80/257 | 31 | 48/133 | 36 | 32/124 | 26 |

Use of Services and Supports

FTF condition participants attended an average of 8.08± 4.27 FTF classes. Seventeen (13%) FTF participants attended no classes, and 77 (58%) attended 10–12 classes. In spite of instructions, 5 control participants attended one FTF class and 5 attended more than one but less than six FTF classes. A total of 112 control participants attended no FTF classes. Table 2 shows the other support services received by participants during the three month study period.

Table 2.

Participants’ Use of Other Supports During Three Month Study Period

| FTF (N=133) | Control (N=126) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | % | N | n | % | |

| Received Support From MH Program In The Past Three Months | 132 | 53 | 40 | 126 | 47 | 37 |

| Counseling Or Therapy With Private Counselor | 132 | 43 | 33 | 125 | 38 | 30 |

| Group Counseling Therapy | 132 | 4 | 3 | 125 | 5 | 4 |

| Telephone Hotline Support | 132 | 7 | 5 | 125 | 3 | 2 |

| Some Other Form Of MH Service/Program | 132 | 13 | 10 | 124 | 11 | 9 |

| Received Any Informal Support Past Three Months | 132 | 101 | 77 | 126 | 87 | 69 |

| Friend Or Family Support | 132 | 99 | 75 | 126 | 82 | 65 |

| Religious Or Spiritual | 132 | 52 | 39 | 125 | 54 | 43 |

| Support Group (Not NAMI) | 132 | 16 | 12 | 126 | 5 | 4 |

| Telephone Hot Line Support | 132 | 9 | 7 | 126 | 4 | 3 |

| Drop In Center | 132 | 1 | 1 | 126 | 0 | .0 |

| Information Present | 132 | 6 | 5 | 126 | 9 | 7 |

| Listserv Or Chat Room | 131 | 10 | 8 | 126 | 9 | 7 |

| Other Support | 131 | 17 | 13 | 125 | 15 | 12 |

| Received Any Support from MH Program or Informal Support | 132 | 106 | 80 | 126 | 97 | 77 |

Comparison of FTF and Control Group Outcomes

FTF participants had significantly greater improvements on indicators of problem-focused coping as measured by empowerment (within the family, services system, and community) and knowledge about mental illness (Table 3). Subjective burden did not differ across groups. In exploratory analyses, FTF participants had significantly greater improvements on the Coping Acceptance subscale which emphasizes the importance of accepting one’s family member’s illness. Of the four coping subscales, Acceptance is most closely related to the FTF model. FTF participants also showed significant reductions in the anxiety subscale of the BSI and significantly improved scores on the FAD problem solving scale compared to controls. The effect sizes for empowerment are in the medium range, while other effect sizes are small. Notably, changes observed on the FAD problem solving and COPE acceptance scales are consistent with reports in the literature in which these scales are used to differentiate clinical from non-clinical samples or changes in clinical samples over time (25, 35–40)

Table 3.

Comparison of FTF and Control after Completion of FTF

| Baseline | 3 Month | Regression Result Condition (Control as Ref) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTF (N=133) |

Control (N=126) |

FTF (N=133) |

Control (N=126) |

||||||||||

| ß(SE) | d.f | t | P | Effect Size* | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| Primary Hypotheses** | |||||||||||||

| Family Member Problem Focused Coping | |||||||||||||

| FES Family Scale1† | 3.4 | .6 | 3.3 | .7 | 3.7 | .6 | 3.5 | .6 | .14(.06) | 102 | 2.39 | .027 | 0.31 |

| FES Service Scale1† | 3.2 | .8 | 3.0 | .9 | 3.4 | .8 | 3.1 | .9 | .23(.08) | 102 | 2.99 | .012 | 0.42 |

| FES Community Scale1† | 2.6 | .7 | 2.3 | .7 | 2.9 | .8 | 2.5 | .7 | .26(.07) | 102 | 3.93 | .005 | 0.50 |

| Knowledge Test2† | 60.6 | 16.8 | 58.5 | 17.8 | 65.4 | 16.9 | 59.1 | 17.4 | 5.28(1.95) | 102 | 2.70 | .016 | 0.40 |

| Family Member Subjective Burden | |||||||||||||

| FEIS Worry Scale3 ξ | 2.7 | .8 | 2.5 | .8 | 2.4 | ± .8 | 2.3 | .7 | .04(.08) | 102 | .47 | .641 | 0.07 |

| FEIS Displeasure Scale4 ξ | 2.8 | .8 | 2.8 | .9 | 2.5 | ± .8 | 2.6 | .9 | −.10(.08) | 102 | −1.21 | .277 | −0.15 |

| Exploratory Analyses | |||||||||||||

| Family Member Emotion Focused Coping | |||||||||||||

| COPE Positive Scale5† | 11.6 | 3.0 | 11.6 | 3.3 | 11.9 | 2.6 | 11.7 | 3.1 | .25(.27) | 102 | .95 | .345 | 0.12 |

| COPE Denial Scale5ξ | 4.9 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 2.0 | −.24(.17) | 102 | −1.37 | .174 | −0.18 |

| COPE Emotional Scale5† | 12.1 | 3.3 | 12.1 | 3.0 | 12.2 | 3.3 | 11.7 | 3.1 | .40(.33) | 102 | 1.21 | .229 | 0.17 |

| COPE Acceptance Scale5† | 13.0 | 2.3 | 12.7 | 2.4 | 13.7 | 2.0 | 12.7 | 2.4 | .74(.26) | 102 | 2.82 | .006 | 0.38 |

| Family Member Psychological Distress | |||||||||||||

| CESD Depression Scale6 ξ | 8.6 | 7.3 | 9.1 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 8.5 | 6.8 | −.94(.67) | 101 | −1.42 | .159 | −0.18 |

| BSI Global Severity Index (T-scores)7 ξ | 51.8 | 9.0 | 52.3 | 9.4 | 49.9 | 8.7 | 51.9 | 9.1 | −1.62(.91) | 100 | −1.76 | .081 | −0.22 |

| BSI Somatization Scale (T-scores)8 ξ | 48.2 | 8.2 | 50.1 | 8.9 | 48.4 | 8.6 | 50.0 | 8.7 | −0.46(.92) | 100 | −0.51 | .614 | −0.06 |

| BSI Depression Scale (T-scores)8 ξ | 52.0 | 9.2 | 51.4 | 9.8 | 50.2 | 8.8 | 51.3 | 9.5 | −1.23(.954) | 100 | −1.29 | .198 | −0.16 |

| BSI Anxiety Scale (T-scores)8 ξ | 52.5 | 9.1 | 52.6 | 9.7 | 50.3 | 8.0 | 52.4 | 9.3 | −1.95(.939) | 100 | −2.08 | .040 | −0.263 |

| Family System Functioning | |||||||||||||

| FAD General Functioning Scale9 ξ | 24.8 | 6.6 | 25.9 | 6.6 | 24.1 | 6.0 | 24.8 | 6.8 | −.13(.64) | 101 | −.20 | .846 | −0.03 |

| FAD Problem Solving Scale10 ξ | 13.0 | 3.0 | 13.1 | 3.0 | 12.1 | 2.6 | 12.9 | 2.8 | −.70(.29) | 101 | −2.38 | .019 | −0.30 |

| FPSC Affirming Communication11† | 10.7 | 2.8 | 10.6 | 3.1 | 11.0 | 2.9 | 10.5 | 3.1 | .50(.32) | 101 | 1.55 | .125 | 0.21 |

| FPSC Incendiary Communication11 ξ | 5.9 | 3.4 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 2.8 | −.43(.32) | 102 | −1.35 | .180 | −0.17 |

Range 1–5,

Range 0–100,

Range 0–4,

Range 1–5,

Range 4–16,

Range 0–42,

Range 33–81,

Range 38–81,

Range 12–48,

Range 6–24,

Range 0–15

Effect Size=Group Difference of LSMeans/SQRT [Var(residual)+ Var(intercept)]

p values reflect correction for multiple comparisons

The higher the score the better (e.g., better knowledge, better coping)

The higher the score, the worse (e.g., more denial, more worry, more depression symptoms)

When comparing FTF participants who attended at least one FTF class (N=116) to control, the differences between FTF and control observed in the completer analysis above persisted. In addition, this narrower sample showed significantly reduced depression as measured by the CES-D (FTF baseline 8.7±7.4. Control Baseline 9.1±7.4; FTF 3-Month 7.1±6.6. Control 3-month 8.5±6.8, ß(SE)= −1.43(.65), t=−2.19, df=98, p=.031) and reduced overall distress measured by the BSI-total ((FTF baseline 51.9±9.1. Control Baseline 52.3±9.4; FTF 3-Month 49.6±8.4. Control 3-month 51.9±9.1, ß(SE)= −2.01(.93), t=−2.17, df=98, p=.032)

Discussion

This study provides empirical support that NAMI’s FTF program helps family members of individuals with mental illness in several ways. Consistent with our previous studies, FTF increased the participant’s empowerment within the family, service system and community. Knowledge about mental illness increased extending our previous finding that evaluated only self-reported knowledge.

Exploratory analyses suggest additional benefits of FTF that have not been previously evaluated. Emotion-focused coping improved with respect to acceptance of mental illness, the dimension of emotion-focused coping most relevant to FTF’s curriculum. Improvements in the problem solving subscale of the FAD suggest that FTF may influence how family members solve internal problems and navigate emotional difficulties. Though the exploratory nature of this aim requires replication, such a finding is noteworthy given FTF’s brevity and its reliance on the participation of the family member without the individual with illness.

Our study also found that FTF reduced the anxiety scores of participants. This finding is consistent with Pickett-Schenk’s (2006) study of the Journey of Hope in which that family-led course improved the well-being of family members (19). It is also noteworthy that the secondary analyses including only individuals who attended at least one FTF session found that FTF produced significantly reduced depression and overall distress. This is important because it models the real-life use of FTF, in that one must attend the program sessions (not just be randomized to do so) to glean such benefits.

The quantitative findings of our current study remarkably echo findings of our qualitative work on FTF, which suggested that the growth in empowerment and coping as well as reductions in distress together produced very meaningful benefits in the lives of FTF participants (41). Lucksted et al. (2008) used rigorous qualitative methods to understand how FTF achieved its impact and found that individuals who completed FTF experienced marked immediate positive global benefits with the promise of longer term growth. They also found that these benefits could be understood in terms of self-help theory, stress/coping and trauma/recovery models Dr. Burland’s original vision for FTF as a self-help program extended beyond empowerment, knowledge and coping and problem solving skills; she conceived of FTF as a way to change the “consciousness” of family members.

We were surprised that FTF did not reduce subjective illness burden as in our preliminary studies. One possibility is that this study’s sample was different, since the two preliminary studies (21, 22) did not require randomization and had much higher consent rates. While randomized trials enhance internal validity, this design has limitations in external validity; the study sample may not be as representative of all FTF participants as our preliminary work. We are addressing this possibility in a substudy focusing on individuals who declined randomization to be reported separately.

In addition to the limitations imposed by a modest consent rate, our study was conducted in one geographic region and relied on participant self-report. Balancing out these limitations were multiple study strengths. Our academic team’s partnership with NAMI permitted us to work with five different NAMI affiliates including a culturally diverse group of participants. We were able to approach every eligible individual taking the classes during the time frame and to conduct a rigorous randomized trial while maintaining the natural delivery of FTF. Blinded raters conducted our assessments with excellent follow up rates.

These results indicate concrete practical benefits to participants of structured self help programs, combining the benefits of a support group and a didactic curriculum. As one example of this new type of mutual assistance interventions, this study highlights the value of such community-based, free, programs as a complement to services within the professional mental health system. Peers with lived experience may have a unique voice in teaching such programs.

To date, FTF is offered in 49 USA states plus Puerto Rico, two Canadian provinces, and three regions in Mexico and Italy. It has over 3500 volunteer teachers and 250 trainers of new teachers. In each locale it is supported by a combination of grass-roots donations and/or municipal mental health funds. The program is free to participants. Since 1991, in the USA, an estimated 250,000 family members have participated in FTF classes nationally (J. Burland, personal communication, August 2010). In each locale, some attendees are later trained to teach the program and a few of these receive still more training to become trainers of future teachers, allowing the model to sustain itself.

Conclusion

FTF is the most widely available and used education and support program for family members of people with mental illnesses. However, until recently its word-of –mouth popularity among participants was not accompanied by effectiveness research. This randomized trial of FTF provides further support that brief family driven educational programs merit consideration as an evidence-based practice (7).

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant no. 1R01 MH72667-01A1)

Footnotes

Disclosures: None for any authors

Contributor Information

Lisa B. Dixon, Email: ldixon@psych.umaryland.edu, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Capitol Health Care Network, Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Baltimore.

Alicia Lucksted, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201

Deborah R. Medoff, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201

Joyce Burland, The National Alliance on Mental Illness, Arlington, Virginia

Bette Stewart, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201

Anthony F. Lehman, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201

Li Juan Fang, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201

Vera Sturm, Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 737 West Baltimore St., 5th Floor, Baltimore, MD 21201

Clayton Brown, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Capitol Health Care Network, Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Baltimore

Aaron Murray-Swank, Washington, D.C., VA Medical Center

References

- 1.Gaite L, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Borra C, et al. Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia in five European countries: The EPSILON study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:283–292. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Magliano L, Marasco C, Fiorillo A, et al. The impact of professional and social network support on the burden of families of patients with schizophrenia in Italy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;10:291–298. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamec C. How to live with a mentally ill person. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsh D. Families and Mental Illness: New Directions in Professional Practice. New York: Praeger Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins J, Schumacher J. Family burden of schizophrenia and depressive illness: specifying the effects of ethnicity, gender and social ecology. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:31–38. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drapalski AL, Marshall T, Seybolt D, Medoff D, Peer J, Leith J, Dixon LB. Unmet needs of families of adults with mental illness and preferences regarding family services. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:655–62. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon L, Dickerson F, Bellack A, et al. The 2009 PORT Psychosocial Treatment Recommendations and Summary Statement. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al. Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: From treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:233–238. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon L, Lucksted A, Stewart B, et al. Therapists’ contacts with family members of persons with serious mental illness in community treatment programs. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:1449–1451. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.11.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al. Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:611–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brand U. European perspectives: a carer’s view. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:96–101. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.1040s2096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernheim KF, Switalski T. Mental health staff and patient’s relatives: how they view each other. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:63–68. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grella A, Grusky O. Families of the seriously mentally ill and their satisfaction with services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:831–835. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatfield AB, Coursey RD, Slaughter J. Family responses to behavior manifestations of mental illness. Innovations Research. 1995;3:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostman M, Hansson L, Andersson K. Family burden, participation in care and mental health – an 11-year comparison of the situation of relatives to compulsorily and voluntarily admitted patients. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2000;46:191–200. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon P, Marcenko M. Families of adults with severe mental illness: their satisfaction with inpatient and outpatient treatment. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1992;16:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burland J. Family-to-family: a trauma-and-recovery model of family education. New Directions in Mental Health Services. 1998;77:33–41. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319987705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickett-Schenk SA, Bennett C, Cook JA, et al. Changes in caregiving satisfaction and information needs among relatives of adults with mental illness: results of a randomized evaluation of a family-led education intervention. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:545–553. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickett-Schenk SA, Cook JA, Steigman P, et al. Psychological well-being and relationship outcomes in a randomized study of family-led education. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1043–1050. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickett-Schenk SA, Lippincott RC, Bennett C, et al. Improving knowledge about mental illness through family-led education: the Journey of Hope. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:49–56. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixon L, Stewart B, Burland J, et al. Pilot study of the effectiveness of the Family-to-Family Education Program. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:965–967. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon L, Lucksted A, Stewart B, Burland J, Brown C, Postrado L, McGuire C, Hoffman M. Outcomes of the Peer-Taught 12-Week Family-to-Family Education Program for Severe Mental Illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:207–215. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tessler R, Gamache G. Family Experience Interview Schedule (FEIS), in the toolkit on evaluating family experiences with severe mental illness. Cambridge, MA: Evaluation Center at HSRI; 1995. (see http://www.hsri.org) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koren P, DeChillo N, Friesen B. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disorders: a brief questionnaire. Rehabilitation Psychology. 1992;37:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon P, Draine J. Subjective burden among family members of mentally ill adults: Relation to stress, coping, and adaptation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:419–427. doi: 10.1037/h0079695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derogatis LR. BSI-18: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. New York: NCS, Pearson; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measure. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS, Lock BZ. The community mental health assessment survey and the CES-D scale. In: Weissman M, Meyers J, Ross C, editors. Community Surveys. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1983;9:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawin KJ, Harrigan MP. Measures of Family Functioning for Research and Practice. New York: Springer Publishing; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI, Thompson AI. Family problem-solving communication (FPSC) In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, editors. Family Assessment: Resiliency, Coping and Adaptation Inventories for Research and Practice. Madison: University of Wisconsin; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat 2001. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. British Medical Journal. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamplin A, Goodyer IM. Family functioning in adolescents at high and low risk for major depressive disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;10:170–9. doi: 10.1007/s007870170023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamplin A, Goodyer IM, Herbert J. Family functioning and parent general health in famlies of adolescents with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;48:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Miller IW, Kohn R, Bishop DS, Epstein NB. Role of the family in recovery and major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1002–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark MS, Smith DS. Changes in family functioning for stroke rehabilitation patients and their families. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 1999;22:171–9. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, et al. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: A study of women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:375–390. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burker EJ, Evon DM, Losielle MM, Finkel JB, Mill MR. Coping predicts depression and disability in heart transplant patients. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1995;59:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucksted A, Stewart B, Forbes C. Benefits and Changes for Family to Family Graduates. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;42:154–66. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]