Abstract

Semiconducting 2D materials, like transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), have gained much attention for their potential in opto-electronic devices, valleytronic schemes, and semi-conducting to metallic phase engineering. However, like graphene and other atomically thin materials, they lose key properties when placed on a substrate like silicon, including quenching of photoluminescence, distorted crystalline structure, and rough surface morphology. The ability to protect these properties of monolayer TMDs, such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), on standard Si-based substrates, will enable their use in opto-electronic devices and scientific investigations. Here we show that an atomically thin buffer layer of hexagonal-boron nitride (hBN) protects the range of key opto-electronic, structural, and morphological properties of monolayer MoS2 on Si-based substrates. The hBN buffer restores sharp diffraction patterns, improves monolayer flatness by nearly two-orders of magnitude, and causes over an order of magnitude enhancement in photoluminescence, compared to bare Si and SiO2 substrates. Our demonstration provides a way of integrating MoS2 and other 2D monolayers onto standard Si-substrates, thus furthering their technological applications and scientific investigations.

In recent years, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have gained much attention as semiconducting van der Waals materials that can be obtained in monolayer form1,2,3,4,5. Analogous to the technological importance of graphene for its electronic properties, the presence of a direct band gap in the visible part of the spectrum2,3, as well as large optical absorption6,7,8,9 and photoconductivity10,11,12 in TMDs, particularly monolayer MoS2, have cemented their importance in opto-electronic devices and applications, such as solar cell devices9,13,14,15, photodetectors16,17,18, and other flexible opto-electronics19. Recent demonstrations have suggested the utility of MoS2 in spin and valleytronic devices20,21,22, as well as nanoelectronic devices with metallic and semiconducting phases23,24,25. However, like most atomically thin 2D materials, when placed on a substrate, interactions impact key opto-electronic, structural, and physical properties of monolayer MoS2, preventing its full realization for potential technological applications. For example, quenching of photoluminescence on silicon2,3 inhibits its utility in silicon-integrated valleytronic and spintronic devices. Similarly, diffuse electron diffraction patterns on Si and SiO226 suggest a distorted crystalline structure or poor surface morphology, which impacts device performance27. Substrate interactions also inhibit the study of phase-engineered MoS2 opto-electronic devices23,24, where crystalline structure provides an important characterization tool for the different metallic and semiconducting phases. Thus the ability to integrate monolayer MoS2 onto standard Si-devices, while simultaneously protecting a wide range of its key properties, is important for scientific and technological applications of MoS2.

Given the practical requirements of substrates for 2D materials, a number of studies have explored substrate interactions for MoS2 and other 2D crystals2,3,4,26,28,29,30,31. In MoS2, electron probes of the surface structure noted the lack of a sharp diffraction pattern for monolayer samples on Si and SiO2 for mechanically exfoliated, as well as in chemical vapor deposition (CVD) grown crystals26. Atomic force microscopy studies have shown a strong dependence of surface roughness on the underlying substrate29. Similarly, reports of photoluminescence quenching on Si2,3 and SiO24,28 were attributed to charge transfer from the substrate to monolayer MoS24,28. Other bulk substrates4 such as hBN, LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 were shown to protect photoluminescence, by preventing such a charge transfer, but these lack easy-integration into standard electronics processing technologies. On the other hand, atomically thin sheets of hBN on Si-based substrates can easily be integrated into Si-based electronic devices and have been shown to improve electron mobilities6,32,33. However, the ability of an atomically thin buffer layer to protect optical properties by preventing charge transfer34, or to restore sharp crystallinity by screening substrate interactions, remains unexplored. In general, a suitable solution to integrate monolayer MoS2 into standard Si-based processing technologies, while protecting the wide range of opto-electronic, structural and morphological properties of MoS2 remains elusive.

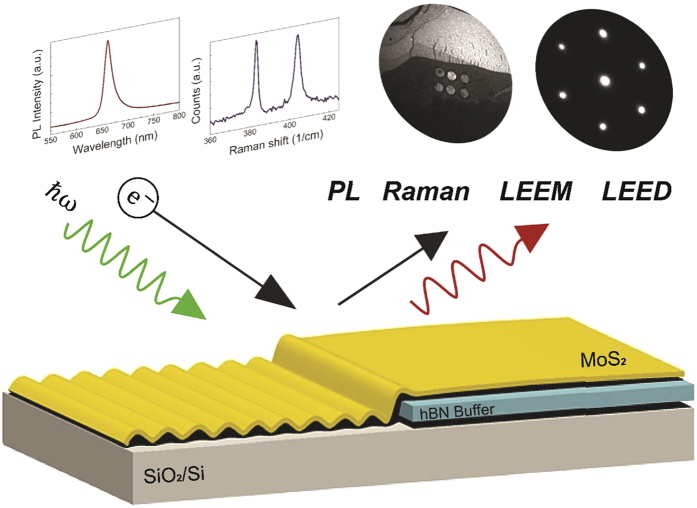

In this article, we demonstrate that an atomically thin buffer layer of hBN simultaneously protects the range of key opto-electronic, structural and morphological properties of monolayer MoS2 on Si-based substrates (Fig. 1). Using microprobe-Low Energy Electron Diffraction (μ-LEED), we show that monolayer MoS2 on bare Si and SiO2 substrates exhibits a diffuse diffraction pattern and a warped surface morphology. On the other hand, the atomically thin hBN buffer layer restores sharp diffraction patterns and results in an extremely flat 2D morphology, with over an order of magnitude less surface roughness. Using micro-photoluminescence and micro-Raman, we further show that the photoluminescence and Raman with the hBN buffer is over two orders of magnitude larger than on bare Si, and is enhanced compared to even suspended samples. This ability to protect a wide range of key properties of monolayer MoS2 on Si-based substrates thus enables sophisticated applications such as valleytronics20,21,22 and phase-engineered devices23,24,25, where the preservation of multiple intrinsic properties of MoS2 are simultaneously required.

Figure 1. Schematic of the characterization of monolayer MoS2 with an atomically thin hBN buffer on Si-based substrates.

We characterize a range of key properties including photoluminescence (PL), Raman, Low Energy Electron Microscope (LEEM) images, Low Energy Electron Diffraction (LEED), and surface morphology of the monolayer with and without the buffer. On the bare substrate, we observe diffuse electron diffraction, quenched PL, quenched Raman, and a rough surface. The presence of the hBN buffer results in an order of magnitude stronger PL, Raman, sharper electron diffraction, and flat surface morphologies.

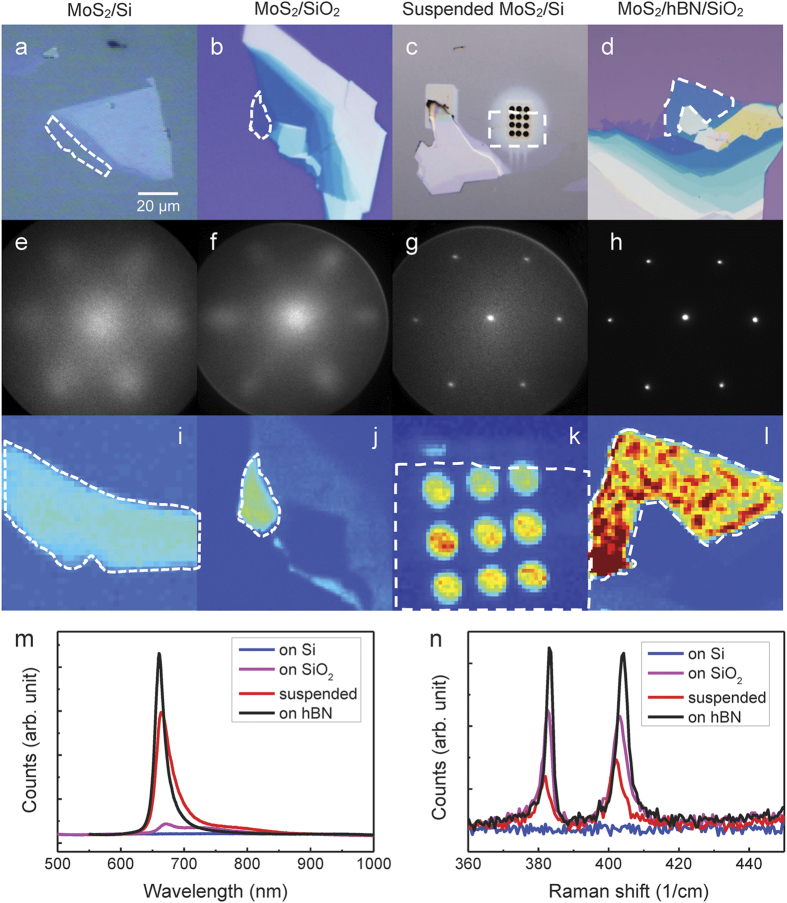

To study the effect of an atomically thin hBN buffer layer between monolayer MoS2 and Si based substrates, we prepared a variety of mechanically exfoliated samples using a viscoelastic stamp35. First, mono- to few-layer samples of MoS2 were directly exfoliated on bare Si and SiO2. These were compared to monolayer flakes suspended on a grid of 2.5 μm holes on Si. Finally, atomically thin buffer layers of hBN with 1–5 nm thickness were first exfoliated onto SiO2/Si, followed by exfoliation of larger MoS2 flakes on top. These structures were annealed at 200 °C for a few hours in an ultrahigh vacuum chamber. Further details of sample preparation are presented in the Methods Section. Optical images of the different samples are shown in Fig. 2(a–d), with the regions of monolayer MoS2 identified by the dotted white line.

Figure 2. Optical, μ-LEED pattern, PL and Raman spectra of monolayer MoS2 on different substrates.

(a–d) shows optical images of the MoS2 flakes, with monolayer areas outlined (white dashed line). In (c), the black circles are 2.5 μm diameter holes drilled into the Si substrate by focused ion beam with a suspended monolayer MoS2 on top. (e–h) shows the μ-LEED pattern of monolayer MoS2 using an electron beam of 250 nm diameter at 50 eV. Relatively weak and diffuse diffraction patterns are obtained for monolayer MoS2 on top of Si and SiO2, whereas for suspended MoS2 and MoS2 on top of hBN buffer, sharp, pristine diffraction patterns are observed. (i–l) are intensity maps of the PL peak with the color-scale optimized individually for visibility. Comparison of PL signal strength and Raman spectra of different samples are given in (m,n), respectively. The monolayer resting on the hBN buffer shows more than an order of magnitude increase in PL over the monolayer on bare Si or SiO2.

To study the structural and surface morphological properties of the MoS2 flakes, we used a Low Energy Electron Microscope (LEEM) capable of measuring spatially resolved electron diffraction patterns with sub-micron resolution. Opto-electronic properties were studied using commercial micro-PL and micro-Raman setups. Details of experimental conditions are presented in the Methods Section.

Electron diffraction obtained from monolayer MoS2 placed on Si and SiO2 substrates (Fig. 2e,f) shows a significantly weakened and diffuse diffraction pattern compared to suspended samples (Fig. 2g), indicating structural disorder or surface roughness. Similarly, PL maps (Fig. 2i–l) of the MoS2 flakes on the different substrates allow us to distinguish the regions of monolayer, but show a significantly weakened PL on the Si and SiO2 substrates compared to the suspended sample (Fig. 2m). We also observe a quenched Raman signal on Si (Fig. 2n). This weak electron diffraction, photoluminescence, and Raman on Si-based substrates limit the utility and integrability of MoS2 in standard opto-electronic devices. In contrast, the presence of an atomically thin buffer layer of hBN protects the range of key structural and opto-electronic properties of MoS2. As seen in Fig. 2(h,m,n), a protective buffer layer of hBN recovers a sharp diffraction pattern, enhanced photoluminescence and Raman from monolayer MoS2 by reducing substrate interactions.

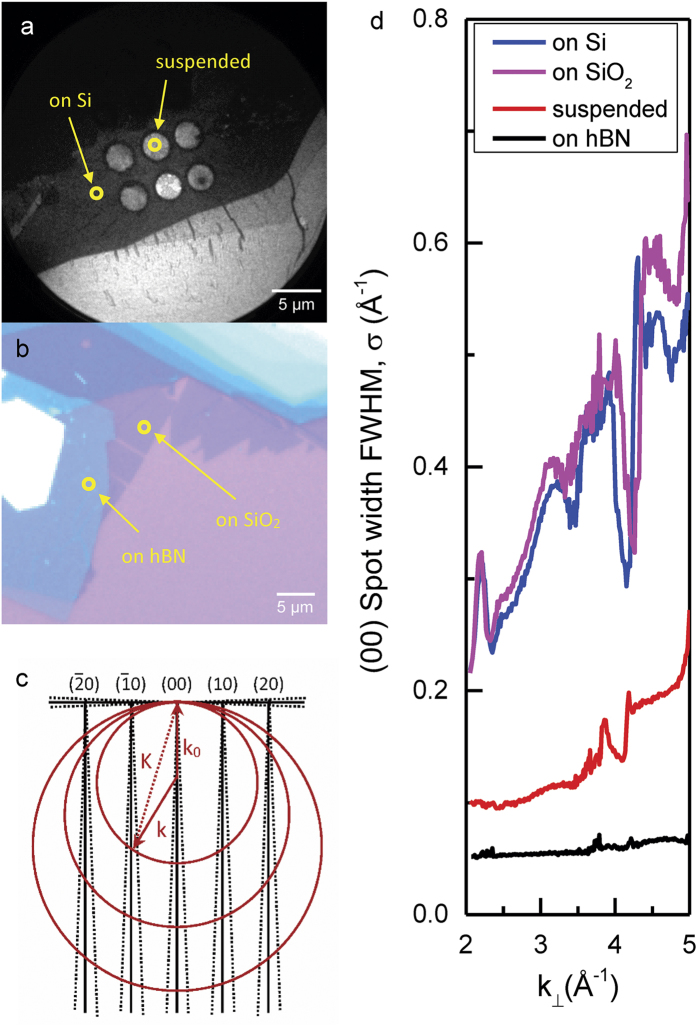

To further explore the role of hBN in protecting these properties in MoS2 and its potential applicability to other 2D monolayers, we study electron diffraction as a function of incident electron energy. The protective layer of hBN can be as thin as ~1 nm, as shown in Figs S1 and S2. In particular, we measure the broadening of the diffracted electron beam for different MoS2 samples (Fig. 3). This allows us to distinguish between two important mechanisms that cause diffuse electron diffraction – a) lattice distortions or defects in the crystal structure, or b) surface roughness of the 2D crystal. In the case of lattice distortions, the broadening in the diffuse diffraction pattern is independent of incident electron energy36. On the other hand, surface roughness leads to a linear increase in the FWHM of the diffuse diffraction pattern versus incident electron energy37,38. In this case, the roughness causes the scattered electron wave to propagate in directions deviating from the specular direction, with increasing deviations for increasing incident electron energy, as illustrated in Fig. 3(c).

Figure 3. Comparing surface roughness of monolayer MoS2 on different substrates.

(a) LEEM images of MoS2 flakes sitting on top of a holey Si substrate. (b) Optical image of an MoS2 flake on SiO2 with hBN buffer in between. Markers in (a,b) indicate positions where detailed LEED spot profile analyses were done. (c) explains the mechanism that causes broadening of the observed LEED diffraction pattern. A rough surface produces diffraction beams which spread out as a cones perpendicular to the sample surface, causing increased broadening with increasing incident electron energy. (d) The FWHM of the specular (00) diffraction beam–σ, with respect to the incident electron wave vector k⊥. Superimposed on the resonant features due to few-layer effects, the overall linear increase in σ indicates a high degree of surface roughness of the MoS2 on bare Si and SiO2. A smaller slope in suspended MoS2 shows a much reduced, but non-zero surface roughness in suspended samples, while the hBN buffer results in yet another order of magnitude decrease in surface roughness.

By plotting the FWHM of the (00) diffraction beam (σ) versus incident electron wave vector k⊥ for monolayer MoS2 on different substrates (Fig. 3d), the mechanism for diffraction broadening can be elucidated. (Details of the fitting process are in the Methods Section). For the Si and SiO2 substrates, we clearly see a linearly increasing σ superimposed on the resonant features resulting from structural effect in the samples. This indicates a high degree of roughness of the MoS2 monolayer on top of Si and SiO2. In comparison, one sees a much smaller σ, with a smaller linear increase in the suspended sample, indicating that the suspended sample exhibits much lower, but non-negligible surface roughness. In contrast, virtually no broadening of the diffraction pattern is detected for MoS2 on hBN with almost no increase in σ as a function of the incident electron energy, indicating an extremely flat 2D monolayer.

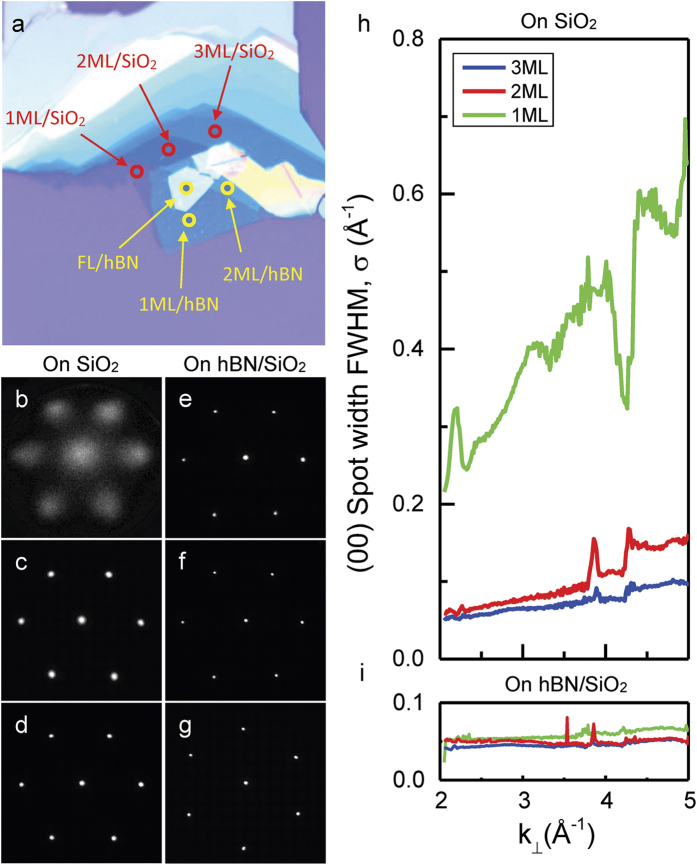

Figure 4 compares the surface roughness for MoS2 flakes of different thickness on both SiO2 and hBN. Monolayer of MoS2 shows the highest roughness on SiO2 while films of greater thickness rapidly relax to form flat films. On the other hand, MoS2 films of all thicknesses show fairly flat topologies on hBN. While our results typically explore samples of few-nm thick hBN, Fig. S1 shows that we obtain a sharp diffraction pattern and an extremely flat 2D monolayer even for a ~1 nm thick hBN buffer layer. Assuming that broadening of diffraction beams is caused by a Gaussian distribution of surface normal, surface roughness of the MoS2 film can be quantified by the relation Δθ = Δk‖/2 k⊥, with a corresponding magnitude of 4.0°, 0.58°, and 0.48° for 1 ML, 2 ML, and 3 ML MoS2 on SiO2, respectively. We see a comparable value of 4.0° for 1 ML MoS2 on bare Si. For suspended monolayer MoS2, surface roughness can similarly be quantified as 0.7°, in agreement with previous experimental39 and theoretical27 results. In contrast, the roughness on hBN is given by 0.08°, reduced by more than an order of magnitude compared to SiO2, Si or even the suspended samples. From our LEED measurements and analysis, we see that the surface roughness of monolayer MoS2 on few-nm thick hBN is comparable to bulk MoS2, which is consistent with previous AFM studies where the surface roughness of monolayer MoS2 on bulk hBN was comparable to bulk MoS229.

Figure 4. Surface roughness for mono-, bi- and few-layer MoS2 on SiO2 and on hBN buffer.

(a) Optical image of a MoS2 flake lying partially on top of SiO2 and partially on top of a hBN buffer. (b–d) shows the μ-LEED pattern of 1 ML, 2 ML and 3 ML MoS2 on SiO2 and (e–g) shows the μ-LEED pattern of 1 ML, 2 ML and few layers MoS2 on hBN. All LEED are taken at 50 eV. (h) The FWHM of the specular (00) diffraction beam–σ, versus incident electron wave vector k⊥. The slope of the overall linear increase of σ versus k⊥ shows the decreasing surface roughness from mono- to bi- to few-layer MoS2 on SiO2. On the other hand, MoS2 on hBN displays negligible amount of beam broadening for all thickness.

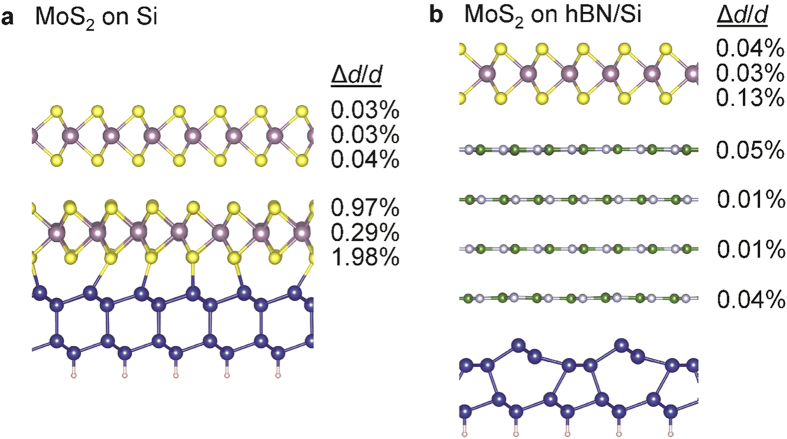

In order to further study the interaction of MoS2 with Si and hBN/Si substrates, we performed density functional theory calculations (Fig. 5) to understand our experimental observations (See Methods section for details). For 2 ML MoS2 directly deposited on Si (111), the bottom MoS2 layer is significantly distorted with an in-plane S–S distance fluctuation of 1.98% (Fig. 5a). We attribute the distortion to bond formation between the bottom S and the surface Si atoms, as the shortest Si–S distance is 2.39 Å, which is comparable to the calculated Si–Si bond length (2.36 Å) and only 10% larger than the Si–S bond length in SiS2 (2.13 Å)40. This implies that any Si surface roughness is transferred to the MoS2 ML. The top MoS2 layer of the 2 ML structure (and any subsequent layer farther away from the interface) is largely unaffected by interactions with the substrate because of weak van der Waals bonds between MoS2 layers, which are much weaker than intralayer bonds. This result agrees with the experimental observation that the roughness of MoS2 decreases for increasing numbers of MLs. In contrast, the MoS2 ML distortions are one order of magnitude smaller (0.13% at most) if deposited on the 4 ML hBN/Si (111) surface (Fig. 5b). This is also attributed to the weak van der Waals bonds between layers and agrees with the flatness of MoS2 on the hBN/Si surface observed in experiment. In addition, hBN interacts weakly with the substrate, as evident from the 2 × 1 reconstruction of the Si(111) surface41, which shows that the Si surface atoms interact weakly with hBN. The smallest Si–N and Si–B distances are 3.21 Å and 3.28 Å, respectively, which are similar to the van der Waals bond length between hBN layers (3.35 Å)42. Moreover, the hBN layers are not distorted by the Si substrate. Therefore, as a result of the weak van der Waals interaction between all adjacent layers in the MoS2/hBN/Si heterostructure, the hBN layers and the MoS2 ML on top are weakly distorted, which agrees with the observed low roughness of both hBN and MoS2 when deposited sequentially on Si (111).

Figure 5. Density functional theory calculations of atomic interactions between MoS2 and Si or hBN/Si surfaces.

Relative variation of the in-plane lattice constant (Δd/d) for each atomic layer due to MoS2-substrate interactions for (a) 2 ML MoS2 on Si (111) and (b) 1 ML MoS2 on 4 ML hBN on Si (111). (a) The bottom MoS2 layer interacts strongly with dangling bonds on the Si surface and gets distorted, while the structure of the top MoS2 layer is largely unaffected due to the weak van der Waals bond between the two layers. Si–S atoms with a distance shorter than 2.6 Å are connected with bonds for illustration. (b) Inserting 4 MLs of hBN between MoS2 and the Si substrate significantly suppresses their interaction and distortion, as evident by the small fluctuation of in-plane bond lengths of MoS2 and the 2 × 1 surface reconstruction of Si, due to weak van der Waals bonds between adjacent layers.

In the triad of 2D materials – graphene as a metal, transition metal dichalcogenides as semiconductors, and hBN as an insulator, the role of hBN in protecting the electronic32,33,43 and structural properties33,43 of graphene has been previously reported. These properties also extend to the protection of other 2D monolayer properties, such as MoS2, using bulk hBN, due to its inert chemical form, lack of dangling bonds, and flatness44,45. Our results show that hBN’s protective capabilities can be achieved even with just a few atomic layers. We see that even with a few atomically thin layers of hBN on SiO2/Si (Fig. S2), we obtain a stable, flat platform, which thereby prevents the overlying 2D monolayer from conforming to the roughness of the substrate.

Besides providing a stable, flat platform, atomically thin hBN needs to also screen interactions arising from the underlying Si-based substrate, which is not a consideration for bulk hBN substrates. DFT calculations for MoS2 sitting directly atop Si, show a large distribution in the bond lengths in MoS2, due to substrate interactions. Such distortions contribute to structural and morphological deformities observed via the diffuse crystalline patterns and quenched Raman signals, as well as modification of the electronic structure and optical responses13,46. In contrast, in the presence of an atomically thin layer of hBN, the bonds in MoS2 are minimally distorted, with hBN acting as a barrier layer to minimize interactions with the Si substrate. Thus the ability of few-layer hBN to provide a flat platform and to minimize substrate interactions, provides insight into the observation of morphologically flat and undistorted crystals of monolayer MoS2.

In addition to improvements in surface flatness and lattice distortion playing a role in protecting the opto-electronic properties6,32,33, such as the PL enhancement seen here, we also expect that the few nm layer of hBN acts as a barrier to charge transfer from the SiO2/Si substrate. This has been previously attributed as an important factor in PL quenching4,47. Lastly, we also note here the importance of annealing and cleaning the MoS2/hBN heterostructure, which results in further improvements in the PL (Fig. S1), presumably due to removal of impurities and trapped states at the MoS2/hBN interface48. Thus, overall we expect that the PL enhancement seen here is due to a combination of multiple factors – decreased surface roughness and lattice distortion due to reduced substrate interaction in the presence of the hBN buffer; the action of the hBN buffer as a barrier to charge transfer from the substrate; and decreased impurity/trapped states after annealing of the heterostructure sample.

In conclusion, we have shown that an atomically thin buffer layer of hBN simultaneously protects a range of key properties of monolayer MoS2 on Si-based substrates. The atomically-thin hBN buffer allows for easy integration of monolayer MoS2 into standard electronics devices, thus enhancing its utility in valleytronics, phase engineered nanoscale electronics, and other opto-electronic devices. Our results also have obvious implications for incorporating other 2D monolayers into standard Si-based devices, while protecting their opto-electronic, structural and morphological properties.

Methods

Sample preparation

MoS2 flakes are prepared by exfoliation of MoS2 single crystals supplied by Manchester Nanomaterials with the well-known scotch tape technique49. We transferred the MoS2 flakes onto different substrates and created the MoS2/hBN/SiO2 heterostructure by an all-dry transfer method using a viscoelastic stamp (GelFilm from Gel-Pak) and a home-built micro-manipulator35. For MoS2 on SiO2, we used SiO2/Si substrates with 300 nm of thermal oxide, which was first cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with acetone and then rinsed by methanol. For MoS2 on Si, an oxide free Si surface is prepared by flash cleaning of the Si(111) wafer to a temperature close to the melting point of Si in the ultrahigh vacuum chamber (UHV) in LEEM. Sample cleanliness and oxide removal is confirmed by appearance of sharp (7 × 7) reconstructed surface with low energy electron diffraction50. For suspended MoS2 flakes, hole of diameters of 2.5 μm and depth of 6 μm were drilled on the SiO2/Si substrate by focused ion beam (FEI Helios NanoLab G3 UC). Before MoS2 transfer, substrates with holes were first annealed in UHV chamber at 200 °C to remove Ga contamination from the ion milling process. For MoS2/hBN/SiO2 heterostructures, SiO2/Si substrates were first cleaned by wet chemical method, as described above. hBN flakes of approximately few nm in thickness were prepared by exfoliation of an hBN single crystal (Manchester Nanomaterials) and then transferred onto the SiO2/Si substrate using the GelFilm. Thin hBN flakes of uniform thickness were identified by AFM (Agilent 5500 AFM). MoS2 flakes were transferred and positioned on top of the flat hBN flake using another GelFilm. The samples were then cleaned and annealed in an UHV chamber in preparation for μ-LEED and surface characterization measurements as described below. The cleaning and annealing process was also critical to observing the significant, order-of-magnitude enhancements in PL (Fig. S1b).

μ-LEED and Surface Roughness Characterization

Crystallinity and surface roughness of the MoS2 flakes were investigated using a low energy electron microscope (LEEM) (Elmitec SPELEEM), which enables high resolution imaging of large sample areas (>100 μm) at resolution better than 10 nm, as well as microprobe-diffraction imaging. This allows access of structural information in sub-micron selected areas of less than 250 nm. LEEM uses very low energy electrons of few eV to image surfaces; hence it is extremely sensitive to surface contamination. Samples introduced in the LEEM imaging chamber are cleaned either by mild annealing at 200 °C for several hours or by illumination of electron beams which remove contamination from local area38. Samples cleaned by either method give similar diffraction patterns, revealing the crystallinity of the MoS2 samples. We do not observe any degradation of crystallinity by performing any further annealing or electron illumination. Charging of the sample surface occurs during imaging, in particular, when the MoS2 samples are on top of insulating substrates such as SiO2. In our studies, we are able to eliminate detrimental charging effects by simultaneously illuminating the sample with an intense UV pulsed laser beam, which generates enough photoexcited carriers to neutralize any charging effects. Similarly, by using a very small incident electron beam of less than 250 nm in diameter during diffraction pattern imaging (μ-LEED), very little charging of the surface was observed. This could again be compensated by a very weak photon beam if needed.

Optical Characterization

Raman and photoluminescence characterization of the MoS2 flakes were performed with a Nanofinder 30 (Tokyo instruments) with an excitation laser wavelength of 532 nm. Spatially resolved spot sizes of 0.5 μm were typically achieved in the measurement. PL spectra are taken at power of 1 mW and an exposure time of 10 s. Raman spectra are taken at a power of 2 mW, and an exposure time of 10 s with 5 accumulations.

First-Principles Calculations

Density Functional Theory calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package51 with projector-augmented waves52 and a cutoff of 350 eV. We used the optB86b-vdW exchange-correlation functional53 to account for the van der Waals interaction between the layered materials, which yields accurate lattice parameters for MoS254. Simulation supercells containing 230 (2 ML MoS2 on Si) and 443 (1 ML MoS2 on 4 ML hBN on Si) atoms were used to simulate the layer-substrate interactions. The positions of the Si atoms on the opposite side of the slab were fixed to the bulk values during atomic relaxation, and dangling bonds were passivated with H atoms. The structures are relaxed until the force on each atom is smaller than 8 × 10−3 eV/Å.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Man, M. K. L. et al. Protecting the properties of monolayer MoS2 on silicon based substrates with an atomically thin buffer. Sci. Rep. 6, 20890; doi: 10.1038/srep20890 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GS and EK were supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER award through Grant No. DMR-1254314. Computational resources were provided by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. ST acknowledges funding supported by the U.S. Army Research Office through a MURI grant# W911NF-11-1-0362. ST and KMD acknowledge funding support by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through a fellowship (#L13521). SK gratefully acknowledges support from NSF ECCS 1351424. ADM and GG thank the LDRD program at LANL for funding for this work.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.K.L.M., S.D.J. and A.W. carried out all experiments and sample preparations. G.S. and E.K. designed, performed, and analyzed the density functional theory calculations. K.M.D. supervised all aspects of the project. G.G., A.M., S.K. and S.T. provided expertise and discussed about the results. All authors contributed in discussion and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Li H. et al. From Bulk to Monolayer MoS2: Evolution of Raman Scattering. Advanced Functional Materials 22, 1385–1390, doi: 10.1002/adfm.201102111 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F., Lee C., Hone J., Shan J. & Heinz T. F. Atomically thin MoS(2): a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys Rev Lett 105, 136805 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuschner N. et al. Photoluminescence of freestanding single- and few-layerMoS2. Physical Review B 89, 125406, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.125406 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Photoluminescence of monolayer MoS2 on LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 substrates. Nanoscale 6, 15248–15254, doi: 10.1039/c4nr04602a (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazyev O. V. & Kis A. MoS2 and semiconductors in the flatland. Materials Today 18, 20–30, doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2014.07.005 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. H. et al. Flexible and transparent MoS2 field-effect transistors on hexagonal boron nitride-graphene heterostructures. ACS Nano 7, 7931–7936, doi: 10.1021/nn402954e (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britnell L. et al. Strong light-matter interactions in heterostructures of atomically thin films. Science 340, 1311–1314, doi: 10.1126/science.1235547 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y. et al. Polarization-dependent optical absorption of MoS(2) for refractive index sensing. Sci Rep 4, 7523, doi: 10.1038/srep07523 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi M., Palummo M. & Grossman J. C. Extraordinary sunlight absorption and one nanometer thick photovoltaics using two-dimensional monolayer materials. Nano letters 13, 3664–3670, doi: 10.1021/nl401544y (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. et al. Ultrafast Intrinsic Photoresponse and Direct Evidence of Sub-gap States in Liquid Phase Exfoliated MoS2 Thin Films. Sci Rep 5, 11272, doi: 10.1038/srep11272 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchi M. M., Polyushkin D. K., Pospischil A. & Mueller T. Mechanisms of photoconductivity in atomically thin MoS2. Nano letters 14, 6165–6170, doi: 10.1021/nl502339q (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham G. et al. Photoconductivity of solution-processed MoS2 films. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 1, 6899–6904, doi: 10.1039/c3tc31402b (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Qian X., Huang C.-W. & Li J. Strain-engineered artificial atom as a broad-spectrum solar energy funnel. Nature Photonics 6, 866–872, doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2012.285 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M. L. et al. Monolayer MoS2 heterojunction solar cells. ACS Nano 8, 8317–8322, doi: 10.1021/nn502776h (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana M. et al. Electron-hole transport and photovoltaic effect in gated MoS2 Schottky junctions. Sci Rep 3, 1634, doi: 10.1038/srep01634 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. et al. Ultrahigh-gain photodetectors based on atomically thin graphene-MoS2 heterostructures. Sci Rep 4, 3826, doi: 10.1038/srep03826 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sanchez O., Lembke D., Kayci M., Radenovic A. & Kis A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat Nanotechnol 8, 497–501, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.100 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. et al. Single-layer MoS2 phototransistors. ACS Nano 6, 74–80, doi: 10.1021/nn2024557 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Kis A., Coleman J. N. & Strano M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat Nanotechnol 7, 699–712, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.193 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism of monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat Commun 3, 887, doi: 10.1038/ncomms1882 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai C. et al. Many-body effects in valleytronics: direct measurement of valley lifetimes in single-layer MoS2. Nano letters 14, 202–206, doi: 10.1021/nl403742j (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z. Y., Cheng Y. C. & Schwingenschlogl U. Giant spin-orbit-induced spin splitting in two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. Physical Review B 84, 153402, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.153402 (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kappera R. et al. Phase-engineered low-resistance contacts for ultrathin MoS2 transistors. Nature materials 13, 1128–1134, doi: 10.1038/nmat4080 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G. et al. Coherent atomic and electronic heterostructures of single-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 6, 7311–7317, doi: 10.1021/nn302422x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. C., Dumcenco D. O., Huang Y. S. & Suenaga K. Atomic mechanism of the semiconducting-to-metallic phase transition in single-layered MoS2. Nat Nanotechnol 9, 391–396, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.64 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh P.-C. et al. Probing substrate-dependent long-range surface structure of single-layer and multilayerMoS2 by low-energy electron microscopy and microprobe diffraction. Physical Review B 89, 155408, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.89.155408 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miró P., Ghorbani-Asl M. & Heine T. Spontaneous Ripple Formation in MoS2 Monolayers: Electronic Structure and Transport Effects. Advanced Materials 25, 5473–5475, doi: 10.1002/adma.201301492 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscema M., Steele G. A., van der Zant H. S. J. & Castellanos-Gomez A. The effect of the substrate on the Raman and photoluminescence emission of single-layer MoS2. Nano Research 7, 561–571, doi: 10.1007/s12274-014-0424-0 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quereda J., Castellanos-Gomez A., Agrait N. & Rubio-Bollinger G. Single-layer MoS2 roughness and sliding friction quenching by interaction with atomically flat substrates. Applied Physics Letters 105, 053111, doi: 10.1063/1.4892650 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.-K. et al. Growth of Large-Area and Highly Crystalline MoS2 Thin Layers on Insulating Substrates. Nano letters 12, 1538–1544, doi: 10.1021/nl2043612 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q. et al. Epitaxial monolayer MoS2 on mica with novel photoluminescence. Nano letters 13, 3870–3877, doi: 10.1021/nl401938t (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X. et al. Multi-terminal transport measurements of MoS2 using a van der Waals heterostructure device platform. Nat Nanotechnol 10, 534–540, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.70 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean C. R. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat Nanotechnol 5, 722–726, doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.172 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. H. et al. Dielectric screening in atomically thin boron nitride nanosheets. Nano letters 15, 218–223, doi: 10.1021/nl503411a (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Gomez A. et al. Deterministic transfer of two-dimensional materials by all-dry viscoelastic stamping. 2D Materials 1, 011002, doi: 10.1088/2053-1583/1/1/011002 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henzler M. Measurement of surface defects by low-energy electron diffraction. Applied Physics A Solids and Surfaces 34, 205–214, doi: 10.1007/bf00616574 (1984). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knox K. R. et al. Spectromicroscopy of single and multilayer graphene supported by a weakly interacting substrate. Physical Review B 78, 201408, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.78.201408 (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli A. et al. Corrugation in exfoliated graphene: an electron microscopy and diffraction study. ACS Nano 4, 4879–4889, doi: 10.1021/nn101116n (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brivio J., Alexander D. T. L. & Kis A. Ripples and Layers in Ultrathin MoS2 Membranes. Nano letters 11, 5148–5153, doi: 10.1021/nl2022288 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. & Krebs B. Silicon disulphide and silicon diselenide: a reinvestigation. Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Crystallography and Crystal Chemistry 38, 1270–1272, doi: 10.1107/s0567740882005469 (1982). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey K. C. New π-Bonded Chain Model for Si(111)-(2 × 1) Surface. Physical Review Letters 47, 1913–1917, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.47.1913 (1981). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brager A. X-ray examination of the structure of boron nitride. Acta Physicochim URSS 7, 699–706 (1937). [Google Scholar]

- Decker R. et al. Local electronic properties of graphene on a BN substrate via scanning tunneling microscopy. Nano letters 11, 2291–2295, doi: 10.1021/nl2005115 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudin K. N., Scuseria G. E. & Yakobson B. I. C2F,BN, and C nanoshell elasticity fromab initiocomputations. Physical Review B 64, 235406, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.64.235406 (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song L. et al. Large scale growth and characterization of atomic hexagonal boron nitride layers. Nano letters 10, 3209–3215, doi: 10.1021/nl1022139 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li Y.-L., Araujo C. M., Luo W. & Ahuja R. Single-layer MoS2 as an efficient photocatalyst. Catalysis Science & Technology 3, 2214, doi: 10.1039/c3cy00207a (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanu U., Islam M. R., Tetard L. & Khondaker S. I. Photoluminescence quenching in gold–MoS2 hybrid nanoflakes. Sci Rep 4, 5575, doi: 10.1038/srep05575 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Stepanov P., Gray M. & Lau C. N. Annealing and transport studies of suspended molybdenum disulfide devices. Nanotechnology 26, 105709, doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/26/10/105709 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669, doi: 10.1126/science.1102896 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telieps W. & Bauer E. The (7 × 7) ↔ (1 × 1) phase transition on Si(111). Surface Science 162, 163–168, doi: 10.1016/0039-6028(85)90890-8 (1985). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G. & Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes forab initiototal-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Physical Review B 54, 11169–11186, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G. & Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Physical Review B 59, 1758–1775, doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758 (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klimes J., Bowler D. R. & Michaelides A. Chemical accuracy for the van der Waals density functional. Journal of physics. Condensed matter : an Institute of Physics journal 22, 022201, doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/2/022201 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peelaers H. & Van de Walle C. G. First-principles study of van der Waals interactions in MoS2 and MoO3. Journal of physics. Condensed matter: an Institute of Physics journal 26, 305502, doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/26/30/305502 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.