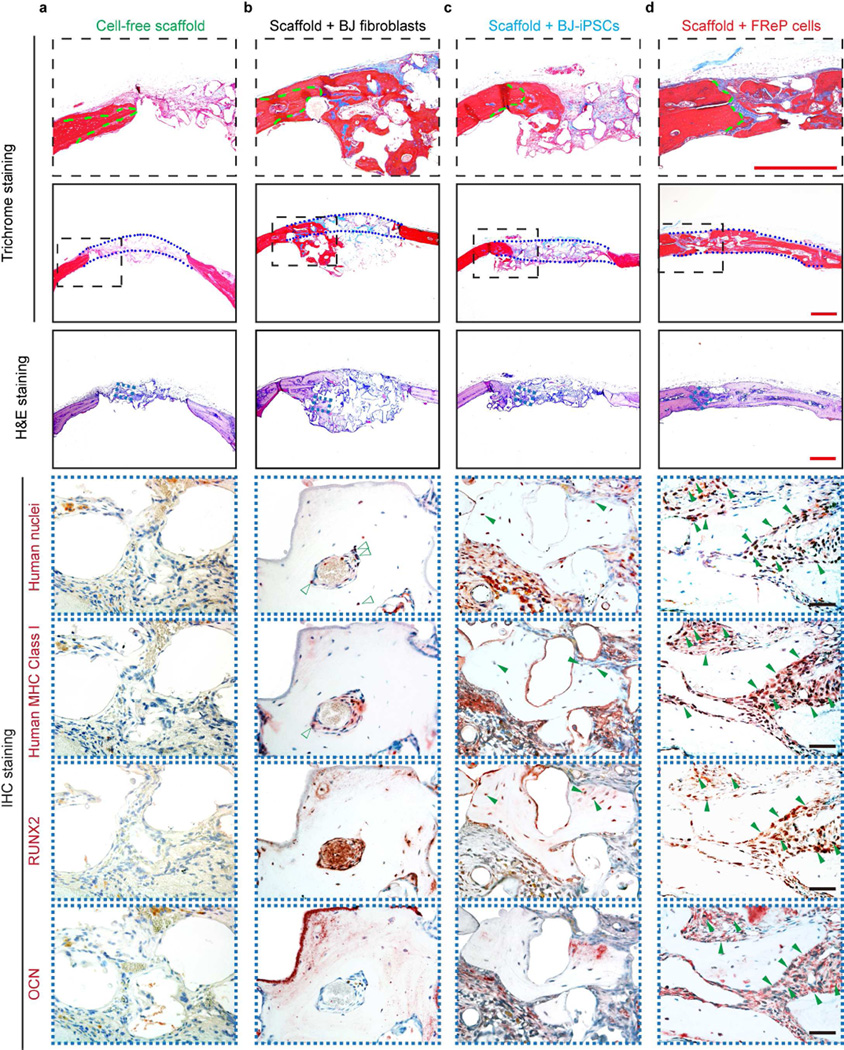

Fig. 6. Engraftment, persistence, and osteogenesis of FReP cells in critical-sized SCID mouse calvarial defects at week 8 post-implantation.

(a) H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining confirmed that only minimal bone regeneration occurred in the group implanted with cell-free scaffold alone, while (b) implantation of BJ-fibroblasts resulted in bone formation underneath the calvarial defect with obvious ‘cyst-like bone voids’ in the newly generated bone tissue. (c) The newly formed bone tissue was predominantly observed at the edge of the defects in BJ-iPSC group. (d) On the contrary, implantation with FReP cells led to a mineralized bony bridge connecting the two defect ends without ectopic bone formation. In Masson Trichrome staining, the matured bone is stained in red, and osteoid is stained in blue. Green dotted lines outlined the initial edges of the calvarial defect, while blue dotted lines outlined the implantation area, respectively. Furthermore, immunostaining of human nuclei and MHC Class I as well as osteogenic markers, RUNX2 and OCN, revealed BJ-iPSCs and FReP cells underwent osteogenic differentiation (solid green arrows) in active osteogenic regions of the defects, while BJ fibroblasts (open green arrows) were only detected in the fibrosis area instead of newly formed bone tissues. Bar = 500 µm (red) or 50 µm (black).