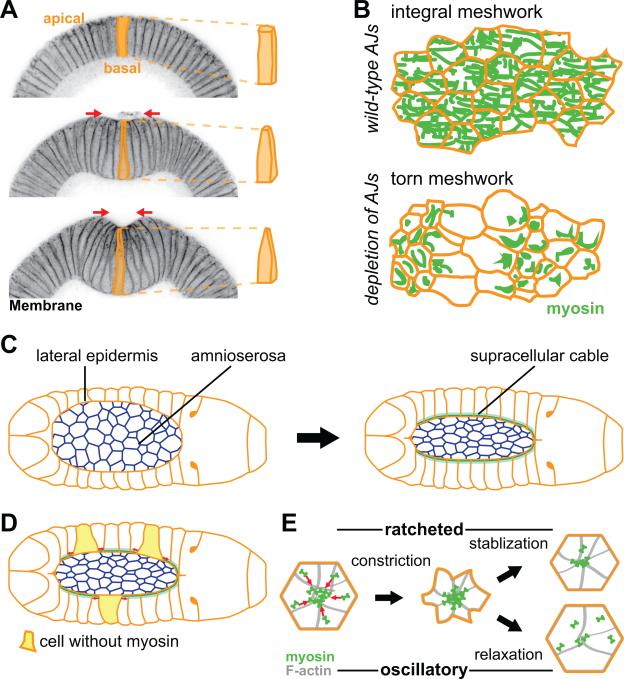

Figure 3. Evidence for AJ and actomyosin based force transmission in vivo.

(A) Apical constriction drives folding of the ventral tissue (ventral furrow formation) in the early Drosophila embryo. The left panels are cross-sections of staged embryos, stained for a membrane marker, undergoing ventral furrow formation. Cells are initially columnar (top) and then apically constrict to become wedged shape (middle and bottom), driving invagination of the tissue. (B) Illustration showing importance of AJs in transmitting tension across a constricting tissue. Myosin forms a supracellular meshwork that spans the constricting tissue (top). Depletion of any AJs component results in tears in the supracellular cytoskeletal meshwork (bottom). (C) Schematic of dorsal closure process. Amnioserosa cells apically constrict, while lateral epidermis forms a supracellular actomyosin cable (green) that also contracts the amnioserosa tissue. (D) In a mosaic animal, epidermal cells that express myosin stretch (red arrows) cells that do not express myosin (yellow cells). (E) Schematic of the apical surface of a cell undergoing ratcheted or oscillatory constriction. Initially, both cells constrict, however the decrease in cell area is stabilized and epithelial tension is facilitated by ratcheted constriction (top). In contrast, the cell shape is not stabilized and relaxes during oscillatory constrictions (bottom).