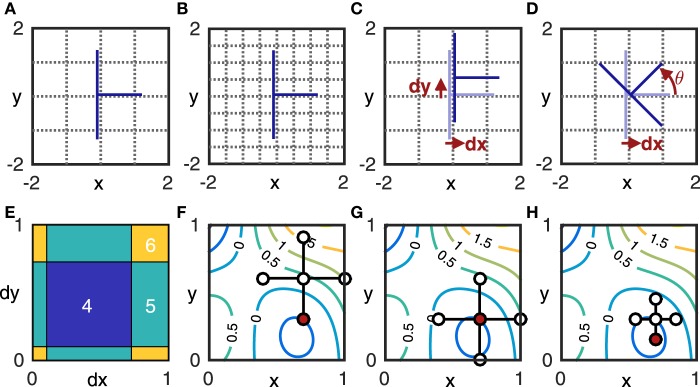

Figure 2.

Components of numerical methods used in this study. (A,B) show box-counting in 2D on an idealized skeletonized root in blue: at box size s = 1 the root intersects N (s) = 6 boxes (A), at s = 1∕2, N (s) = 9 (B). (C,D) show the effect of placement on the box-count with s = 1: translation by dx and dy yields N = 4; translation by dx and rotation by θ yields N = 3. Taking N = 3 as the minimum value, the box-count estimates Nϵ in (A,C) include quantization error ϵA = 3 and ϵC = 1, respectively. (E) shows the box-count Nϵ as a function J (dx, dy) at θ = 0. It generalizes (C) to show the box-count values for all combinations of 0 < dx < 1 and 0 < dy < 1. Note that the function jumps by integer values and is thus not continuously differentiable, but exhibits the following symmetry: J (dx + a, dy, θ) = J (dx, dy + a, θ) = J (dx, dy, θ) for any integer a, since a translation of the grid in any direction by the grid-size s yields the same grid. The same symmetry is obtained for rotation by multiples of π ∕ 2. (F–H) illustrate pattern search on the contour plot of an unknown function Z = f (x, y). Given a starting point (x0, y0) to serve as the center for a five-point stencil and a step-size Δv, the function is evaluated in step one (F) at the center and four outlying points (x0 ± Δv, y0 ± Δv). The lowest value of Z (indicated in red) is found at (x0, y0 − Δv), which thus becomes the stencil center for the next step. In step two (G), the function is again evaluated at each of the five points of the new stencil. The minimum value (red) is found at the center this time, so the stencil is not moved for the next step, but the step-size is reduced to Δv∕2. In step three (H) the function is evaluated at the five points of the new stencil and a new minimum is identified. This process continues until the step-size reaches a chosen lower bound.