Abstract

Objective

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have a high risk of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD). We developed CVD quality indicators (QIs) for screening and use in Rheumatology clinics.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature on CVD risk reduction in RA and the general population was conducted. Based on the best practices identified from this review, a draft set of 12 candidate QIs were presented to a Canadian panel of rheumatologists and cardiologists (n=6) from three academic centers to achieve consensus on the QI specifications. The resulting 11 QIs were then evaluated by an online modified-Delphi panel of multidisciplinary health professionals and patients (n = 43) to determine their relevance, validity and feasibility in three rounds of online voting and threaded discussion using a modified RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Methodology.

Results

Response rates for the online panel were 86%. All 11 QIs were rated as highly relevant, valid and feasible (median rating ≥7 on a 1–9 scale) with no significant disagreement. The final QI set addresses the following themes: communication to primary care about increased CV risk in RA, CV risk assessment, defining smoking status and providing cessation counseling, screening and addressing hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes, exercise recommendations, body mass index screening and lifestyle counseling, minimizing corticosteroid use and communicating to patients at high risk of CVD about the risks/benefits of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Conclusion

Eleven QIs for CVD care in RA patients have been developed and are rated as highly relevant, valid and feasible by an international multidisciplinary panel.

Key Indexing Terms: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Cardiovascular Diseases, Quality Indicators, Health Care, Primary Prevention

Introduction

Patients with RA have approximately a 50% higher mortality rate if they have a cardiovascular event when compared to the general population (1). Although chronic inflammation probably contributes to premature atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction (2), improvements in treatment for RA have not consistently translated into reduced cardiovascular disease (CVD) events (3, 4). Some authors have recently proposed there may be a trend towards a “widening mortality gap” in RA due to CVD, as survival rates from CV events have improved in the general population but have remained stagnant in RA populations (4, 5).

Despite general recognition that patients with RA are at increased risk of CVD events, there is ample evidence that even well established CVD risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia are not identified and managed consistently in RA populations (6–15). One strategy to reduce CVD risk in RA is therefore to better identify and manage modifiable risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia.

Quality Indicators (QIs) are statements about optimum process or outcomes of care that can be further developed into performance measures. Performance measures have a specified numerator, denominator and exclusion criteria. They can be used for measuring the percent adherence to the process or the proportion of patients achieving the desired outcome and are critical for quality improvement initiatives (16).

QIs are often based on guidelines from national or international professional societies but have a greater specificity than the recommendations from which they are derived (16, 17). They can represent either an optimum or minimum standard of care depending on the intended use of the measure (quality improvement versus accountability e.g. in the form of pay for performance or use for accreditation). Although a variety of methodologies exist for developing QIs (17), a key feature of indicator development is the use of high grade evidence combined with expert opinion.

Current QIs for RA focus primarily on the treatment of joint inflammation and the monitoring of drug side effects (18–20). To date, they have not completely addressed the most important cause of mortality in this population: cardiovascular disease. The objective of this study was to develop a set of QIs to address cardiovascular risk factor management in patients with RA for the purposes of quality improvement and research. The intended audience for the proposed indicators is healthcare professionals caring for patients with RA, primarily rheumatologists and other rheumatology providers (e.g., rheumatology nurses, clinical nurse specialists or nurse practitioners). In addition, the indicators are highly relevant to cardiologists, internists and primary care practitioners responsible for the medical management of patients with RA.

Materials and Methods

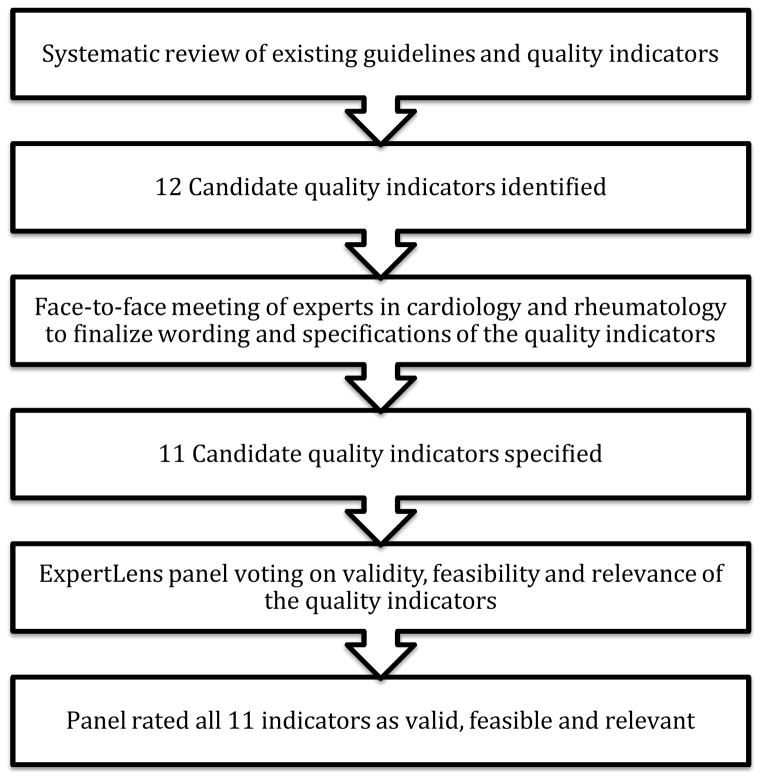

The approach used to develop the CVD QIs is shown in Figure 1. The development of the CVD QIs for RA involved three phases: 1) a systematic review to define the existing best practices for CVD preventive care in RA and drafting of the candidate indicators, 2) an in-person expert panel meeting with 6 experts to achieve consensus regarding the scope, wording and specifications of the candidate measures and 3) an international online modified-Delphi panel [n=43] employing a novel RAND-developed platform to finalize the indicators, rate the relevance, validity, and feasibility to RA care, while also obtaining feedback about whether the measures would be used in clinical practice.

Figure 1.

Methods for developing the quality indicator set for cardiovascular care in rheumatoid arthritis

Phase 1: A systematic review of existing guidelines and indicators and development of background reports

Quality measures are often developed from existing guideline recommendations (17). Therefore in phase 1, a systematic review of existing guidelines and quality indicators in both the general population and RA literature was conducted and relevant manuscripts from the last five years (2008–2013) were included. The detailed methods and results of the systematic review are published elsewhere (21). The results of the systematic review were used to identify best practices for cardiovascular care in patients with RA and to inform the development of candidate QIs. The QIs were worded in a standard format (IF-THEN-BECAUSE) to identify the clinical situation of interest (IF), the recommendation (THEN) and the evidence and rationale for the QI (BECAUSE). A clear numerator, denominator and exclusion criteria were also identified for each QI to ensure accurate measurement of the indicator upon application in a routine clinical practice setting (22).

A report describing each candidate QI and its specifications as well as the supporting guidelines and reported level of evidence were generated for subsequent stages.

Phase 2: Expert consensus meeting to finalize scope, wording and specifications of candidate indicators

The candidate indicators and associated reports were presented to a select group of cardiologists and rheumatologists from three academic centers in Canada (NA, GBJM, DL, SK, JAA-Z, JME). These individuals represented a convenience sample of clinicians and researchers with an expertise in CVD in RA and/or quality improvement. The specifications and wording of the indicators were refined in an in-person meeting and consensus was achieved through an iterative process. These experts were not part of the online modified-Delphi panel in Phase 3.

Phase 3: Online modified-Delphi panel with international experts to finalize the candidate indicators using a modified RAND/UCLA appropriateness methodology

The candidate indicators were then presented to an online international panel using an innovative, iterative, online, previously evaluated platform called ExpertLens (23, 24), which has been previously used to elicit expert opinion on a range of healthcare topics, including the identification of definitional features of Continuous Quality Improvement (25) and of aspirational research goals for preventing suicide (26). Nonetheless, this is the first time the platform has been used for QI development.

ExpertLens is an iterative online system used to obtain and analyze opinions from medium to large groups of people combining a number of approaches including the Delphi, Nominal Group and Crowdsourcing techniques (23). With the online platform a larger number of panelists can be included than in typical RAND/UCLA appropriateness panels, enabling diverse geographical representation, and the findings have been shown to be reproducible among different groups (24). The online panel is therefore more cost and time efficient than typical large international consensus meetings. Additional benefits of the system are the use of unique identifiers, which can avoid dominance of the group by a small number of vocal individuals (23).

Online panel composition and recruitment

A diverse group of 43 expert stakeholders from North America and Europe were invited to participate including cardiologists, rheumatologists and primary care physicians from both academic and non-academic practices. Pharmacists, nurses, clinician scientists, and patients were also represented. Although many participants were recruited based on their prior publications in the area of CVD in RA, effort was also made to include clinicians in community practices and other types of participants including patients. These individuals were identified through a variety of means including National Societies (e.g. Canadian Rheumatology Association, Allied Health Professions Association), patient advocacy groups (e.g., Arthritis Patient Advisory Board of the Arthritis Research Center of Canada) as well as snowball recruitment. Participants were recruited via an email invitation and agreed to participate prior to the panel start date. Participants did not receive financial incentives for participation. The University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board [ethics identification REB13-0210] approved the project and the RAND Human Subjects’ Protection Committee determined this study to be exempt from review.

Panel rating of relevance, validity, feasibility, and likelihood of use of the QIs

Between November 4th and December 3rd 2013, participants took part in a three round ExpertLens process. In Round 1, participants rated QIs on four criteria (see Table 1 for description of criteria). In Round 2, they reviewed the automatically-generated distribution of group’s responses to each question that included: (1) a bar chart showing the frequency of each response category for the group, (2) a group median, (3) interquartile range and (4) participant’s own response to that question (see Appendix Figure 1). Participants also were encouraged to participate in an online, asynchronous, anonymous discussion, which was moderated by CEHB to ensure they remained on-topic and constructive. Finally, in Round 3, participants were requested to revise their Round 1 responses based on group feedback and discussion and share their study experiences by answering a brief series of satisfaction questions. Each round was open for 7 to 14 days, depending on participation rates. Periodic reminders to participate were sent via email to maximize participation.

Table 1.

Description of criterion used to select quality indicators

| Criterion | Question |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Relevance | Please rate the relevance of the above indicator (1=not relevant, 9=relevant). In doing so, consider whether:

|

| Validity | Please rate the validity of the above indicator (1=not valid, 9=valid). In doing so, consider whether:

|

| Feasibility | Please rate the feasibility of the above indicator (1=not feasible, 9=feasible). In doing so, consider whether:

|

| Use | Considering the above quality indicator, please rate how likely (1=not likely, 9=likely) you would be to use or encourage the use of the measure for internal quality improvement in your practice/center. |

Participants were asked to rate candidate QIs on the following four rating criteria during Round 1 and again in Round 3. The first two criteria have been used previously to assess validity and feasibility (27, 28), the third and fourth criteria were formulated during Phase 2 with the expert panelists to assess relevance and likelihood of use. All criteria were Likert-type 1–9 scales with labeled end points. Detailed definitions of each criterion are shown in Table 1.

Analysis of panelist responses

To be included in the final set, indicators had to be rated as highly valid and feasible (median validity and feasibility scores ≥7), with no disagreement among participants. Disagreement was calculated using a formulae that examines the distribution of the ratings according to the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method handbook (29). Disagreement exists when the Interpercentile Range (IPR) (difference between the 30th and 70th percentiles) is larger than the Interpercentile Range Adjusted for Symmetry (IPRAS), which was calculated using the following formulae: IPRAS=2.35+[Asymmetry Index (AI)*1.5] (derivation of the formulae shown in the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method handbook (29)).

Results

The results of the systematic review of existing guidelines and QIs are presented elsewhere (21). Briefly, recommendations and indicators were abstracted from both RA and general population guidelines that were relevant to primary CVD prevention (e.g., CVD risk assessment, lipid, diabetes and hypertension screening, exercise, smoking and lifestyle counseling).

Based on the systematic review results, a set of 12 candidate indicators was drafted and presented to the Phase 2 small expert working group of two cardiologists and four rheumatologists at an in-person meeting (Phase 2, Figure 1). The 12 drafted indicators encompassed the following topics: communication of the importance of CVD care in RA to the primary care provider, CVD risk assessment, smoking status and counseling for cessation, screening for hypertension, communicating to a primary care provider about an elevated blood pressure, blood pressure control, measurement of a fasting lipid profile, dietary counseling, exercise counseling, corticosteroid tapering to lowest dose, and avoidance of NSAIDs in patients at high risk of CVD events.

The expert panel in Phase 2 made recommendations as to the wording of the indicators and the specifications. Major expert panel recommendations included the following:

Outcome measures (or interim outcome measures) such as blood pressure targets should not be included in the QI set because such measures were not felt to be in the rheumatologist’s scope of practice.

Although maintaining a low disease activity state or remission was felt to be important in reducing CVD risk in patients with RA, general treatment of RA and measurement of disease activity was not felt to be within the scope of these QIs because of the focus on QIs that specially address CVD.

Many of the QIs were designed to measure communication between the rheumatologist and other care providers to encourage a cohesive approach to monitoring and caring for CVD risk and to recognize that CVD risk management is a responsibility that is shared between all physicians who care for a patient with RA but is not necessarily the primary responsibility of the rheumatologists.

Frequency of conducting a formal CVD risk assessment was discussed and minimum intervals were proposed in accordance with guideline recommendations. The timing of other measures where there was no guideline for the frequency of measurement was based on the panel’s consensus.

Stand alone QIs that recommended only measuring a risk factor without a specific action (e.g. measuring a lipid profile or ascertaining smoking status) were discouraged as it was felt that this may lead to clinical inertia (e.g. measuring more lipid profiles but not calculating CVD risk or appropriately treating if indicated).

A QI on screening for diabetes was recommended and added to the set.

The QI on dietary counseling was not felt to be within the purview of a rheumatologist and measuring body mass index (BMI) was recommended instead.

A revised set of 11 QIs was selected for presentation to the ExpertLens panelists.

ExpertLens Panel Participant characteristics and participation rates

There were 43 individuals who were invited to participate in the online ExpertLens panel, of which 37 (86.0%) participated. The self-reported characteristics of the ExpertLens participants are shown in Table 2. Twenty-eight completed all three rounds (65%). There were four participants who completed Round 1, but not Round 3, and five who completed Round 3, but not Round 1. During Round 2 (online discussion board), there were 24 discussion threads and 113 discussion comments. As this demographic information was asked during Round 1, a maximum of 32 respondents answered these questions. In a sensitivity analysis, we analyzed the responses from all participants who completed Round 3 and also on those who completed both Round 1 and 3; there were no significant differences (in Table 3 we report the results from individuals who participated in both rounds).

Table 2.

Self-reported ExpertLens participant characteristics (Round 1*)

| Participant characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Professional Background | |

| Physicians | 26 (81.3%) |

| Allied health professionals | 2 (6.3%) |

| Patients | 2 (6.3%) |

| Methodologists/researchers | 1 (3.1%) |

| Physician and methodologist/researcher** | 1 (3.1%) |

| Country | |

| Canada | 14 (43.8%) |

| United States of America | 6 (18.8%) |

| Europe | 9 (28.1%) |

| Other | 1 (3.1%) |

| No response | 2 (6.3%) |

| Urban | 31 (96.9%) |

| Prior Quality Indicator Work | 12 (37.5%) |

| Prior Guideline Work | 16 (50%) |

|

| |

| Health Professional Characteristics (includes physicians and allied health professionals)

| |

| Health Professional Specialty | |

| Rheumatology | 16 (55.2%) |

| Cardiology | 8 (27.6%) |

| Primary care | 3 (10.3%) |

| Other | 2 (6.9%) |

| Years in practice | |

| <5 | 3 (10.3%) |

| 5–10 | 5 (17.2%) |

| 11–20 | 10 (34.5%) |

| >21 | 10 (34.5%) |

| No response | 1 (3.4%) |

| Practice Setting | |

| Community | 3 (10.3%) |

| Academic: clinical/teaching | 18 (62.1%) |

| Academic: research | 6 (20.7%) |

| No response | 2 (6.9%) |

Note only a maximum of 32 participants responded to the demographic questions and all percentages calculated based on this maximum response rate for this section.

Background was mutually exclusive with no original option for methodologist/researcher, however one participant listed themselves as a researcher and clinician which was added here. As shown in practice setting there are potentially six individuals who may better fit this category.

Table 3.

Final validity, feasibility and relevance ratings from the ExpertLens panel on the 11 cardiovascular quality indicators (QI)

| Quality Indicator | Validity | Feasibility | Relevance | Use of QI for local improvement | Disagreement* in any of the domains (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Median Rating (Min-Max) % Agreement (Rating>=7) | |||||

| 1. Communication of increased CVD risk in RA | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (5–9) | 8.0 (5–9) | 8.0 (1–9) | N |

| 88.9% | 85.7% | 92.9% | 82.1% | ||

| 2. CVD risk assessment | 8.0 (5–9) | 7.0 (3–9) | 7.0 (3–9) | 7.5 (3–9) | N |

| 85.7% | 67.9% | 88.9% | 67.9% | ||

| 3. Smoking status and cessation counseling | 9.0 (6–9) | 8.5 (6–9) | 8.5 (6–9) | 9.0 (5–9) | N |

| 96.4% | 92.9% | 100% | 92.9% | ||

| 4. Screening for hypertension | 9.0 (5–9) | 9.0 (7–9) | 9.0 (7–9) | 9.0 (7–9) | N |

| 96.4% | 100% | 96.4% | 100% | ||

| 5. Communication to PCP about a documented high BP | 9.0 (7–9) | 9.0 (7–9) | 9.0 (7–9) | 9.0 (4–9) | N |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 92.6% | ||

| 6. Measurement of a lipid profile | 7.5 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (3–9) | N |

| 82.1% | 89.3% | 85.7% | 82.1% | ||

| 7. Screening for diabetes | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (3–9) | N |

| 89.3% | 82.1% | 92.9% | 85.2% | ||

| 8. Exercise | 8.0 (6–9) | 8.0 (5–9) | 8.0 (5–9) | 8.0 (3–9) | N |

| 96.4% | 85.7% | 89.3% | 77.8% | ||

| 9. BMI screening and lifestyle counseling | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 7.0 (3–9) | N |

| 89.3% | 78.6% | 92.9% | 85.7% | ||

| 10. Minimizing corticosteroid usage | 9.0 (5–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.0 (4–9) | 8.5 (1–9) | N |

| 92.9% | 85.7% | 92.9% | 85.7% | ||

| 11. Communication about risks/benefits of anti-inflammatories in patients at high risk of CV events | 8.0 (4–9) | 7.0 (3–9) | 7.0 (3–9) | 7.0 (1–9) | N |

| 85.2% | 78.6% | 85.7% | 75.0% | ||

The results presented are those obtained from the 28 participants who completed both Round 1 and Round 3 of online voting. Possible range of scores is 1–9.

Disagreement measured using the Interpercentile Range greater than the Interpercentile range adjusted for symmetry (IPR>IPRAS) (29). Disagreement exists when the Interpercentile Range (IPR) (difference between the 30th and 70th percentiles) is larger than the Interpercentile Range Adjusted for Symmetry (IPRAS), which was calculated using the following formulae: IPRAS=2.35+[Asymmetry Index (AI)*1.5]

CVD: Cardiovascular Disease, BMI: Body Mass Index, BP: blood pressure, PCP: primary care physician, RA: rheumatoid arthritis

Cardiovascular Disease Quality Indicators

After Round 2, a few minor changes to the QIs were made based on feedback from earlier rounds and presented to the panel in Round 3. For example, for QI 4 (Screening for hypertension), the specifications of the measure originally suggested at a minimum measuring the blood pressure once per year; however, panelists expressed during Round 2 discussions that this was not frequent enough (especially since many rheumatologic medications impact blood pressure) and the measure was modified to better reflect guideline recommendations which suggest more frequent screening.

In Round 3, all eleven CVD QIs were rated as highly relevant, valid, and feasible by the panelists without significant disagreement (Table 3). Participants also agreed that they were likely to advocate for the QIs to be used in local quality improvement initiatives.

The final indicator statements are shown in Table 4, and the full specifications, including descriptions of the numerator, denominator and relevant exclusions, are shown in the Appendix.

Table 4.

Final set of Eleven Cardiovascular Disease Quality Indicators for Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients

| 1. Communication of increased CV risk in RA: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis, THEN the treating rheumatologist should communicate to the primary care physician, at least once within the last 2 years that patients with RA have an increased cardiovascular risk. |

| 2. CV risk assessment: A) IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN a formal cardiovascular risk assessment according to national guidelines should be done at least once in the first two years after evaluation by a rheumatologist AND B) if low risk it should be repeated once every 5 years; OR C) if initial assessment suggests intermediate or high-risk, THEN treatment of risk factors according to national guidelines should be recommended. |

| 3. Smoking status and cessation counseling: A) IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN their smoking and tobacco use status should be documented at least once in the last year AND B) if they are current smokers or tobacco users they should be counseled to stop smoking. |

| 4. Screening for hypertension: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN their blood pressure should be measured and documented in the medical record at ≥ 80% of clinic visits. |

| 5. Communication to PCP about a documented high blood pressure: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis AND has a blood pressure measured during a rheumatology clinic visit that is elevated (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90) THEN the rheumatologist should recommend that it be repeated and treatment initiated or adjusted if indicated. |

| 6. Measurement of a lipid profile: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN a lipid profile should be done at least once in the first two years after evaluation by a rheumatologist AND A) if low risk according to cardiovascular risk scores, the lipid profile should be repeated once every 5 years; OR B) if cardiovascular risk assessment suggests intermediate or high-risk, then treatment according to national guidelines should be recommended. |

|

7. Screening for diabetes: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN diabetes should be screened for as part of a cardiovascular risk assessment at least once within the first 2 years of evaluation by a rheumatologist and A) once every 5 years in low risk* patients or B) yearly in intermediate or high-risk* patients AND if screening is abnormal, this information should be communicated to the primary care provider for appropriate follow-up and management if indicated. Note: Risk* here denotes risk of diabetes and assessment of diabetes risk is described in detail in the full specifications for the quality indicators (shown in the Appendix). |

| 8. Exercise: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN physical activity goals should be discussed with their rheumatologist at least once yearly. |

| 9. BMI Screening and Lifestyle Counseling: A) IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis THEN their body mass index (BMI) should be documented at least once every year AND B) if they are overweight or obese according to national guidelines they should be counseled to modify their lifestyle. |

| 10. Minimizing corticosteroid usage: IF a patient with rheumatoid arthritis is on oral corticosteroids THEN there should be evidence of intent to taper off the corticosteroids or reduce to the lowest possible dose. |

| 11. Communication about risks/benefits of anti-inflammatories in patients at high risk of CV events: IF a patient has rheumatoid arthritis AND has established cardiovascular disease OR is at intermediate or high cardiovascular risk AND is on a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID or Cox-2 inhibitor) THEN a discussion about the potential cardiovascular risks should occur and be documented. |

Discussion

The proposed set of 11 CVD QIs for RA has been agreed upon as highly relevant, valid and feasible for measurement and quality improvement initiatives in RA by a large international, multidisciplinary panel of healthcare professionals and patients. The recommended QIs comprehensively cover many aspects of CVD preventive care in RA and are evidence-based and aligned with current high-quality guidelines based on our systematic review (21). Where RA guidelines were lacking in evidence to support these measures, it was decided that as a minimum, general population guidelines should be followed and these were used to support and help define the QIs.

The 11 QIs define processes important to CVD preventive care in RA. Risk-adjusted outcome or interim outcome measures (e.g. lipid or blood pressure targets) were not felt to be within the scope of this project as it was determined that screening for CVD risk factors and primary prevention should be a shared responsibility and not solely the responsibility of the rheumatologist. Importantly, in the United States, the National Quality Strategy recognizes care coordination as an important gap in quality measurement (30). The set of CVD QIs are unique as they emphasize communication between providers in caring for patients with RA, which we hope will improve coordination of comorbidity care for patients with RA.

Our work represents the first time ExpertLens has been used for QI development and shows that the online platform had a number of advantages. Typical RAND/UCLA appropriateness panels used for QI development frequently have a limited number of participants (often 9), which limits the diversity among participants and may prevent inclusion of informed patients as included participants are often experts (29). By using the online platform, we were able to get broader representation from a diverse group of international participants. Unfortunately, not all recruited participants ended up providing their expert opinion. This may have been for a variety of reasons. Some participants may not have been available during panel times or decided not to participate. Others may not have received ExpertLens invitation emails, which could have been re-routed to the spam folders of their inbox by their email provider. Nonetheless, our overall participation rate of 86% was excellent and compared favorably with participation rates in other ExpertLens (24) and online Delphi panels with fewer rounds (31).

An advantage of the online platform was the ability to anonymously obtain responses and discussion threads on topics from participants, which avoided dominance of the discussion by a subset of participants. Some participants commented, however, that they would have liked more time to discuss the QIs or would have benefited from a conference call to review certain aspects of the measures. However, by Round 3, general consensus was achieved, and it is unknown if further discussion in person or online would have altered the measures significantly.

To mitigate the potential disadvantages of holding a QI development panel entirely online alluded to above, we first had a small meeting of experts to review the QI specifications and wording. Based on the recommendations of this group, QIs, which only measured clinician documentation of a risk factor, e.g. smoking status, or lipid profile, were discouraged as it was felt they would be unlikely to lead to quality improvement if clinicians were not prompted to “do something” if a risk factor was identified. Therefore, some of the proposed measures included more than one measurement concept (e.g. documenting smoking status AND recommending smoking cessation). This potentially made voting challenging for some of the online participants who may have agreed with one part of the QI, but not another and consequently may have led to lower ratings for some of the presented QIs. As the measures are for quality improvement and not accountability, we feel that it is reasonable that a measurement concept be coupled with an action concept to avoid clinical inertia, while recognizing that it increases the complexity of executing and practically assessing the measure.

An additional strength of this work is the diversity of individuals who participated from around the world. Nonetheless, it should be noted that recruitment of individuals from community practice (especially rural practice), as well as certain physician types (e.g. general internists and primary care practitioners) was challenging because these individuals were harder to identify and recruit. Consequently these groups were underrepresented. As shown in the literature (32), it is possible that panels with a different composition could have voted differently on the proposed indicators. In this case, it is possible that feasibility ratings for some of the indicators may have been lower if the panel composition had included more rheumatologists in community practice. We encourage pilot testing of the indicators and selection of the most appropriate measures depending on the clinical setting.

We plan to further validate the QIs in rheumatology practice. This further work will involve evaluation of the feasibility of measuring the indicators in different practice settings, measurement of inter-rater reliability, assessing whether a gap in care exists and determining how best to implement improvements (22, 33).

In conclusion, patients with RA have a significantly higher rate of death due to CVD than the general population. Ensuring high quality CVD preventive care for patients with RA is one method of potentially mitigating this risk and is in keeping with current RA and general population guidelines. In this study, we proposed a comprehensive set of 11 CVD QIs for patients with RA for the purposes of quality improvement and research. Our work represents the first time ExpertLens has been used for QI development and shows that the online platform had a number of advantages and is a useful tool for QI development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study:

This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). Funding reference number 129628.

Dr. Barber is a PhD candidate and her work is supported by a Health Research Clinical Fellowship from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (AIHS) 2011-ongoing as well as a Rheumatology Postgraduate Fellowship funded by UCB Canada, The Canadian Rheumatology (CRA) Association and The Arthritis Society (TAS) from 2011–2013.

Dr. Marshall is a CIHR Canada Research Chair in Health Services and Systems Research and the Arthur J.E. Child Chair Rheumatology Outcomes Research

Members of the Quality Indicator International Panel (alphabetical order)

Todd J Anderson MD, FRCPC, Professor of Medicine, Head, Department of Cardiac Sciences, Alberta Health Services & the University of Calgary, Director, Libin Cardiovascular Institute

Sandeep Aggarwal MD, FRCPC, Associate Clinical Professor, University of Calgary

Pooneh Akhavan MD MSc, Division of Rheumatology, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto

Christie Bartels MD MS, Assistant Professor Dept of Medicine, Rheumatology Division, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

Carolyn Bell MBBS London, MRCP Rheumatologist for Worcestershire Royal Hospital, Worcester, UK

Gilles Boire MD MSc, Professor, Department of Medicine, Rheumatology Division, University of Sherbrooke

Ailsa Bosworth Chief Executive National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS)

Linda Brown RN, Alberta Health Services

Alexandra Charlton BScPharm, ACPR Pharmacy Clinical Practice Leader Pharmacist, Division of Rheumatology, Alberta Health Services

Shirley Chow MD, FRCPC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto

Cynthia Crowson MS, Statistician III, Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics Associate Professor of Medicine (Rheumatology) and Assistant Professor of Biostatistics, Mayo Clinic

Milan Gupta, MD, FRCPC, Associate Professor of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada; Medical Director, Canadian Cardiovascular Research Network, Brampton, Canada

John G Hanly, MD, FRCPC, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, Dalhousie University; Attending staff rheumatologist, Capital Health, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Alison M Hoens, MSc, BScPT, Physical Therapy Knowledge Broker University of British Columbia Department of Physical Therapy; Member – Arthritis Patient Advisory Board of the Arthritis Research Center of Canada

Wes Jackson MD, CCFP, FCFP, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary

George D. Kitas, MD, PhD, FRCP, Director of Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust and Professor of Clinical Rheumatology, Arthritis Research UK Epidemiology Unit, University of Manchester, UK

Tabitha N. Kung MD, FRCPC, MPH Clinical Associate, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto

Theresa Lupton RN CCRP, Nurse Clinician Rheumatology, Alberta Health Services

Paul MacMullan MB BCh BAO MRCPI, Clinical Assistant Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary

Sherif Moustafa MBBCh Mayo Clinic Arizona

Michael T. Nurmohamed, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Depts of Rheumatology and Internal Medicine, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Sara Partington MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

Athanase D. Protogerou, MD, Hypertension Unit and Cardiovascular Research Laboratory, 1st Department of Propaedeutic Internal Medicine, Laiko Hospital, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Anne-Grete Semb, MD, PhD Preventive Cardio-Rheuma clinic, Department of Rheumatology, Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, Norway

Amanda J. Steiman MD, MSc, FRCPC, Lupus Clinical Research Fellow, Division of Rheumatology, Toronto Western Hospital

Lisa Gale Suter, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, Yale School of Medicine

Deborah Symmons MD FFPH FRCP, Professor of Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Epidemiology, Arthritis Research UK Centre for Epidemiology

Jinoos Yazdany, MD MPH, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco

Footnotes

This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Journal of Rheumatology following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version Development of Cardiovascular Quality Indicators for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Results from an International Expert Panel Using a Novel Online Process is available online at: http://www.jrheum.org/content/42/9/1548.

Contributor Information

Claire E. H. Barber, PhD Candidate, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary.

Deborah A Marshall, Associate Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, Arthur JE Child Chair in Rheumatology Research, University of Calgary.

Nanette Alvarez, Associate Professor, Division of Cardiology, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Calgary, Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta.

G. B. John Mancini, Professor, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia.

Diane Lacaille, Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia; Senior Scientist, Arthritis Research Centre of Canada.

Stephanie Keeling, Associate Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta.

J. Antonio Aviña-Zubieta, Assistant Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia; Research Scientist, Arthritis Research Centre of Canada.

Dmitry Khodyakov, Social/Behavioral Scientist, The RAND Corporation.

Cheryl Barnabe, Assistant Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, ARC Research Scientist.

Peter Faris, Adjunct Associate Professor, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary; Biostatistician, Research Support, Alberta Health Services.

Alexa Smith, Assistant Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Dalhousie University.

Raheem Noormohamed, Student, Department of International Health, John Hopkins University School of Public Health.

Glen Hazlewood, PhD Candidate, Clinical Scholar, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary.

Liam O. Martin, Professor, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Calgary.

John M. Esdaile, Professor of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia; Scientific Director, Arthritis Research Centre of Canada and The Cardiovascular Disease in RA International Panel for Quality Indicator Development.

References

- 1.Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Full LE, Monaco C. Targeting inflammation as a therapeutic strategy in accelerated atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;29:231–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergstrom U, Jacobsson LT, Turesson C. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality remain similar in two cohorts of patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis seen in 1978 and 1995 in Malmo, Sweden. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1600–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radovits BJ, Fransen J, Al Shamma S, Eijsbouts AM, van Riel PL, Laan RF. Excess mortality emerges after 10 years in an inception cohort of early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:362–70. doi: 10.1002/acr.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez A, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Davis JM, 3rd, Therneau TM, et al. The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3583–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai SS, Myles JD, Kaplan MJ. Suboptimal cardiovascular risk factor identification and management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R270. doi: 10.1186/ar4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A, Balint P, Balsa A, Buch MH, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:62–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossec L, Salejan F, Nataf H, Nguyen M, Gaud-Listrat V, Hudry C, et al. Challenges of cardiovascular risk assessment in the routine rheumatology outpatient setting: an observational study of 110 rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:712–7. doi: 10.1002/acr.21935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keeling SO, Teo M, Fung D. Lack of cardiovascular risk assessment in inflammatory arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus patients at a tertiary care center. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1311–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toms TE, Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, Griffiths H, Sattar N, Smith JP, et al. Statin use in rheumatoid arthritis in relation to actual cardiovascular risk: evidence for substantial undertreatment of lipid-associated cardiovascular risk? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:683–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.115717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott IC, Ibrahim F, Johnson D, Scott DL, Kingsley GH. Current limitations in the management of cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartels CM, Kind AJH, Everett C, Mell M, McBride P, Smith M. Low frequency of primary lipid screening among medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1221–30. doi: 10.1002/art.30239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartels CM, Johnson H, Voelker K, Thorpe C, McBride P, Jacobs EA, et al. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on receiving a diagnosis of hypertension among patients with regular primary care. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1281–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.22302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Protogerou AD, Panagiotakos DB, Zampeli E, Argyris AA, Arida K, Konstantonis GD, et al. Arterial hypertension assessed “out-of-office” in a contemporary cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients free of cardiovascular disease is characterized by high prevalence, low awareness, poor control and increased vascular damage-associated “white coat” phenomenon. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R142. doi: 10.1186/ar4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, Milionis HJ, Stavropoulos-Kalinglou A, Nightingale P, Kita MD, et al. Prevalence and associations of hypertension and its control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1477–82. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGlynn EA, Asch SM. Developing a clinical performance measure. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotter T, Blozik E, Scherer M. Methods for the guideline-based development of quality indicators--a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2012;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLean CH, Saag KG, Solomon DH, Morton SC, Sampsel S, Klippel JH. Measuring quality in arthritis care: methods for developing the Arthritis Foundation’s quality indicator set. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:193–202. doi: 10.1002/art.20248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanna D, Arnold EL, Pencharz JN, Grossman JM, Traina SB, Lal A, et al. Measuring process of arthritis care: the Arthritis Foundation’s quality indicator set for rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:211–37. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strombeck B, Petersson IF, Vliet Vlieland TP group EUnW. Health care quality indicators on the management of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: a literature review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:382–90. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barber CE, Smith A, Esdaile JM, Barnabe C, Martin LO, Faris P, Hazlewood G, Noormohamed R, Alvarez N, Mancini GB, Lacaille D, Keeling S, Aviña-Zubieta JA, Marshall D. Best practices for cardiovascular disease prevention in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of guideline recommendations and quality indicators. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015 Feb;67(2):169–79. doi: 10.1002/acr.22419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326:816–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalal S, Khodyakov D, Srinivasan R, Straus S, Adams J. ExpertLens: A system for eliciting opinions from a large pool of non-collocated experts with diverse knowledge. Technol Forecast Soc. 2011;78:1426–44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodyakov D, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, Shekelle P, Foy R, Salem-Schatz S, et al. Conducting online expert panels: a feasibility and experimental replicability study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubenstein L, Khodyakov D, Hempel S, Danz M, Salem-Schatz S, Foy R, et al. How can we recognize continuous quality improvement? Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:6–15. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claassen CA, Pearson JL, Khodyakov D, Satow PM, Gebbia R, Berman AL, et al. Reducing the Burden of Suicide in the U.S.: The Aspirational Research Goals of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention Research Prioritization Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Gillis JZ, Schmajuk G, MacLean CH, Wofsy D, et al. A quality indicator set for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:370–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, Keesey J, Klein DJ, Adams JL, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1515–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR, Lazaro P, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Public Reporting of Quality and Efficiency Measures Workgroup. [Internet Accessed August 21, 2014];Prioritizing the Public in HHS Public Reporting: Using and Improving Information on Quality, Cost, and Coverage to Support Health Care Improvement. 2013 Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/reports.html.

- 31.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coulter I, Adams A, Shekelle P. Impact of varying panel membership on ratings of appropriateness in consensus panels: a comparison of a multi-and single disciplinary panel. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:577–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell SM, Kontopantelis E, Hannon K, Burke M, Barber A, Lester HE. Framework and indicator testing protocol for developing and piloting quality indicators for the UK quality and outcomes framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.