Abstract

Objective

To examine trends in health insurance type among US children and their parents.

Methods

Using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (1998-2011), we linked each child (n=120,521; weighted n≈70 million) with his/her parent(s) and assessed patterns of full-year health insurance type, stratified by income. We examined longitudinal insurance trends using joinpoint regression and further explored these trends with adjusted regression models.

Results

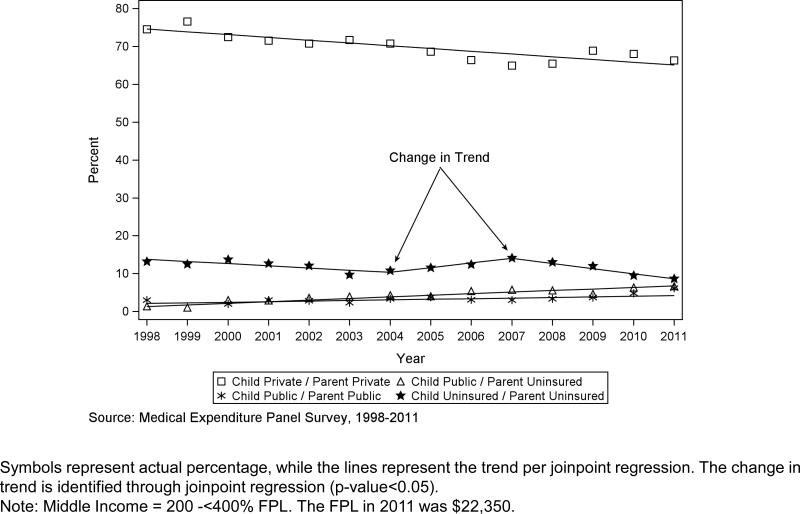

When comparing 1998 to 2011, the percentage of low-income families with both child and parent(s) privately insured decreased from 29.2% to 19.1%, with an estimated decline of −0.86 (95% CI: −1.10, −0.63) unadjusted percentage points per year; middle-income families experienced a drop from 74.5% to 66.3%, a yearly unadjusted percentage point decrease of −0.73 (95% CI: −0.98, −0.48). The discordant pattern of publicly insured children with uninsured parents increased from 10.4% to 27.2% among low-income families; and from 1.4% to 6.7% among middle-income families. Results from adjusted models were similar to joinpoint regression findings.

Conclusions

During the past decade, low- and middle-income US families experienced a decrease in the percentage of child/parent pairs with private health insurance and pairs without insurance. Concurrently, there was a rise in discordant coverage patterns, mainly publicly insured children with uninsured parents.

Keywords: health insurance, access to care, uninsured, family health

INTRODUCTION

Stable health insurance leads to better access to health care services and improved health outcomes.1-4 Over the past decades, political and economic changes have affected access to and affordability of coverage for families in the United States (US), notably steep increases in private health insurance costs. Though some families obtained coverage for their children through expansions in the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), few public coverage options existed for adults (aged 19-64) before 2014.5,6

Parental coverage status has an independent effect on children's health insurance and access to care, regardless of the child's coverage status.7-9 Previous research utilizing a natural experiment that randomized adults to coverage found a causal link between parent and child health insurance status.10 Thus, it is important to consider trends in children's health insurance coverage in conjunction with trends affecting parents. Most past studies of health insurance focused on adults or children separately; those that considered both children and parents did not assess type of coverage.7-14 To address this gap in the literature, we examined full-year patterns of family health insurance coverage type among US children and their parents for 1998 through 2011, stratified by income.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

We analyzed data from 1998 through 2011 of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component (MEPS-HC).15 MEPS-HC respondents are interviewed five times over a two-year period, with an overlapping panel design; annual public use files contain data from a single year for two consecutive panels. Each year of data constitutes a nationally representative sample. Details about the MEPS-HC are available elsewhere.15,16

The study population included children aged 0-17 years, with responses to at least one full year of the survey (n=126,093). We linked each child with parent(s) in the same household to construct child/parent pairs. We excluded children for whom no identifiable parent records could be linked (n=4,048), and for whom insurance information the child or parent was not available for the full year (n=1,524). Our final sample size was 120,521 children, weighted to represent a yearly average of approximately 70 million children in the civilian, non-institutionalized US population.

Constructing Health Insurance Type Variables

The MEPS-HC contains variables for whether a person had health insurance for at least one day in each calendar month of each year, and whether it was public or private insurance. Using these, we constructed variables representing full-year health insurance type, classified as: (1) having private insurance, if a person had insurance in 12 months of the year of which one or more months included private insurance (those with a combination of public and private insurance were included in this category); (2) having public insurance, if a person was insured in 12 months of the year and had public insurance only; and (3) being uninsured, in which the person was reported as having no insurance in one or more months of the year. We included those with a combination of public and private insurance in the private category to match MEPS-HC health insurance variable categorization;15 we considered those who did not have insurance in one or more months of a given year as uninsured because previous research has shown that preventive service rates for patients with partial health insurance are different from those with full-year coverage17 and similar to those with no coverage.18,19

We then created a combined variable that paired full-year health insurance type for a child with that of his/her parent(s). We grouped child and parent type of health insurance into nine mutually exclusive categories [child type/parent(s) type]: private/private; private/public, private/uninsured; public/private; public/public; public/uninsured; uninsured/private; uninsured/public; and uninsured/uninsured. In cases where a child had two parents linked, parent insurance was considered private if at least one parent had any private insurance, regardless of the other parents’ insurance status or type; parental insurance was considered public if both parents had public insurance only, or one parent had public only and the other parent was uninsured; parental insurance was considered uninsured if both parents were uninsured. If the parent and child had the same type of health insurance, their coverage was considered concordant and if the insurance type varied between parent and child, their coverage type was considered discordant.

We based household income stratifications on established MEPS-HC categories: low income [(<200% of the federal poverty level (FPL), combining MEPS-HC poor, near poor and low categories]; middle income (200% to <400% FPL); and high income ( ≥400% FPL).15 The FPL for a family of four was $16,450 in 1998 and $22,350 in 2011.20,21

Analysis

All analyses were stratified by family income categories. We do not report results from high-income families as the majority (88%) had private insurance for both child and parent and all categories had either no statistically significant changes, or too few subjects to assess changes (n<30). We used sampling stratification variables, design weights, and a robust variance estimator in accordance with MEPS guidelines to account for the complex sample design of the survey. This accounts for both the intra-cluster correlation of children within families and intra-person correlation across years.22

We examined the following demographic characteristics for the entire study period as one pooled sample and report the weighted percentage of each characteristic: age (child categories: 0-4, 5-9, 10-13, 14-17; parent categories ≤24, 25-44, ≥45), child race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic/white, non-Hispanic/non-white, Hispanic), region (North, Midwest, South, West), parental education (<12 years or ≥12 years), family composition (1 parent or 2 parents), parental employment (currently employed or unemployed), and child's perceived health status (excellent/very good or good/fair/poor). We conducted descriptive analyses of the prevalence of all nine possible patterns of coverage type for children paired with parent(s), as well as concordant versus discordant insurance coverage. We assessed differences in the distribution of child/parent health insurance type between 1998 and 2011 with chi-square tests of association using SUDAAN version 11.0.1 software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC).

We used joinpoint regression (sometimes called piecewise regression, or segmented regression) to determine if and when coverage patterns showed significant changes throughout the entire study period (Joinpoint Regression Software Version 4.0.4 – May 2013, Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch, Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute).23 Joinpoint regression is often used for two simultaneous goals: 1) to identify statistically significant changes in trend over time (in direction or rate of decrease or increase) and 2) to quantify that change through an annual percentage of change statistic. This approach has been used to assess temporal trends in health insurance, and other health care outcomes.24-26 The null hypothesis in this analysis was no change in trend, and the alternative hypothesis was a significant increase or decrease in the prevalence of each health insurance coverage pattern. The minimum number of joinpoints allowed was zero (i.e. a straight line over time), indicating no change in child and parent health insurance coverage patterns over time. The maximum number of joinpoints was set at two, based on an algorithm taking into account the number of time points available,23 with one exception: the child only public/parent any private, middle-income group was limited to only one joinpoint due to small cell sizes (n<30) in the years 1998-2000, and thus had fewer time points available. A Monte Carlo permutation method was used to select the model with the best fit, and yearly percentage point changes were calculated for each segment. Statistically significant changes are those that increase or decrease over time and are significantly different than an annual percent change of zero (no change over time).

To account for potential differences between child/parent health insurance types in our analysis of change patterns over time, we used trend segments identified in joinpoint regression analyses with multinomial logistic regression to allow inclusion of potential confounders. In these models, the child and parent combined health insurance type was the outcome variable (nine categories) and year was the primary independent variable. For the low-income models, all nine categories were included in the outcome variable; however, for the middle-income models, the child private/parent public and child uninsured/parent public categories were excluded due to small and/or zero cells (n<30). We adjusted for all demographic characteristics examined, as they are known to influence health insurance coverage.7,27-29 Marginal effects for year were calculated for each model, and are represented as an adjusted yearly percentage point change. Multinomial logistic regression models were conducted and marginal effects were calculated using STATA 11.2 IC (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Throughout this paper, we do not report estimates based on sample sizes of <30; as estimates based on such sample sizes are not reliable. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Our Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt.

RESULTS

Children from this sample of low- and middle-income families in the US predominantly lived in the south, had excellent or very good health status, were non-Hispanic/white, had parents with ≥12 years of education, had employed parents, and had two parents living in the household. Children and parents from low-income families tended to be younger than those from middle-income families.

Among children from low- and middle-income families, the prevalence of full-year child/parent health insurance type changed significantly between 1998 and 2011 for several groups including [child type/parent(s) type]: private/private; public/private, public/public, public/uninsured, uninsured/private, and uninsured/uninsured.

Trends in Private Insurance Coverage

The percentage of child/parent pairs with private insurance decreased steadily from 29.2% in 1998 to 19.1% in 2011 for low-income families (<200% FPL); yearly unadjusted percentage point decrease of −0.86 per year [95% confidence interval (CI) −1.10, −0.63] from 1998-2011. The prevalence of middle-income pairs with child and parent(s) privately insured fell significantly from 74.5% in 1998 to 66.3% in 2011; yearly unadjusted percentage point decrease of −0.73 (95% CI: −0.98, −0.48) between 1998 and 2011.

Trends in Uninsurance

The prevalence of low-income child/parent pairs with both child and parent uninsured showed a decrease overall from 26.3% in 1998 to 14.8% in 2011; yearly unadjusted percentage point decrease of −0.81 (95% CI: −1.05, −0.58). Middle-income uninsured pairs also saw a decrease from 13.2% in 1998 to 8.7% in 2011; from 1998-2004 there was a yearly unadjusted percentage point decrease of −0.58 (95% CI: −1.01, −0.15) and from 2007-2011, the yearly percentage point decrease was −1.36 (95% CI: −2.19, −0.54).

Trends in Discordant Insurance Coverage

Overall, discordant coverage increased from 23.2% to 42.1% for low-income families. The prevalence of publicly insured children with uninsured parents increased from 10.4% in 1998 to 27.2% in 2011; yearly unadjusted percentage point increase of 1.74 (95% CI: 1.36, 2.12) from 1998-2003, which continued rising, though less dramatically, by 0.98 (95% CI: 0.75, 1.20) percentage points per year between 2003 and 2011. Discordant coverage increased from 9.3% to 18.8% for middle-income families. The prevalence of publicly insured children with uninsured parents increased from 1.4% in 1998 to 6.7% in 2011; a yearly unadjusted percentage point increase of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.51).

Yearly percentage point changes from all adjusted multinomial logistic regression models were consistent in magnitude and direction with those found in joinpoint regression with two exceptions: the trends were similar in direction, but were no longer statistically significant for middle-income families with publicly insured children and privately insured parents and low-income families with uninsured children and publicly insured parents.

DISCUSSION

Type of health insurance coverage patterns changed significantly for low- and middle-income US children and their parents from 1998 to 2011. Families saw significant decreases in the percentage of child/parent pairs with full-year, private health insurance and pairs without coverage. This coincided with a significant increase in the percentage of families with discordant coverage. Specifically, we found an increase in publicly insured children with uninsured parents, suggesting that when families lost private coverage, they were able to obtain public health insurance for their children only. Decreases in private coverage, concurrent with increases in public coverage could be due to ‘crowd out’- the movement of privately insured individuals to public insurance.30 Reports of crowd-out have been mixed. For example, one study found for every 100 children who became eligible for public insurance; 4 gained public coverage, yet only 2 of them were uninsured prior to gaining coverage, thus crowd out explained half of the increase.31 Other studies, however, found little or no evidence of crowd out.32,33 In this study we see a much larger increase in publicly insured children with uninsured parents as compared to publicly insured children with privately insured parents. Thus, the increasing cost of private health insurance coupled with reductions in employer-sponsored insurance offerings and the historical lack of opportunities for adults to gain public coverage, likely account for the changes reported here.

When faced with unaffordable coverage options and/or reductions in benefit packages, low- and middle-income families were forced to look beyond employer-sponsored, private coverage.34,35 During the time period studied, many states expanded their children's health insurance programs while simultaneously limiting eligibility and public insurance enrollment opportunities for adults.36 The changes in health insurance type seen in this study were not explained by differences in child or parent characteristics, as evidenced by the consistent results between unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Further research is needed to assess the impact of these increasing discordant family coverage patterns.

Implications

Despite improvements in children's coverage rates, this study suggests a trend of coverage loss for parents that could negatively impact the whole family. Insured children with uninsured parents have higher odds of experiencing health insurance coverage gaps and unmet health care needs, as compared to insured children with insured parents.8,37 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) calls for state Medicaid program expansions to cover adults earning ≤138% of the FPL and for health insurance marketplaces to allow individuals not offered health insurance through their employer the ability to purchase coverage on their own; millions have gained coverage through these new opportunities.38,39 Few coverage options are available for low-income adults living in states that chose not to expand their Medicaid programs.40 Without expansions in Medicaid, uninsured parents will need to rely on private health insurance through health insurance marketplaces. Though federal tax credits exist for low- and middle-income families to help pay for marketplace premiums, cost is still reported as a barrier to coverage.41

The unknown future of CHIP is cause for concern for low- and middle- income families.42 Without CHIP, millions of children may become uninsured through the ‘family glitch’ (i.e., adults would not quality for ACA subsidies because they have the income to afford coverage for themselves, even if they cannot afford the cost of the premium for the family).43,44 This study uncovered a disturbing historical trend in families’ insurance coverage: as children gained coverage, parents lost coverage at an alarming rate. Thus, as changes in health insurance options and eligibility continue to occur, it will remain important to monitor the stability of family coverage. In addition to demonstrating novel methods for this continued evaluation of family coverage patterns, we also demonstrate how joinpoint analyses can be used in future analyses for researchers to track longitudinal changes in the slope and direction of trends in health insurance coverage.

Limitations

Our analyses were limited by existing MEPS-HC variables. As with all on self-reported data, response bias remains a possibility. However, the MEPS-HC survey asks several questions about health insurance status and type at various time points, and survey staff logically edits responses for consistency across variables. The MEPS is a nationally representative data set that does not account for state-level differences stemming from individual state policies, which differentially expanded and contracted public health insurance programs during the study time period.

Conclusions

From 1998 to 2011, low- and middle-income US families experienced a decrease in the percentage of child/parent pairs with private health insurance and pairs without insurance. Concurrently, there was a rise in discordant coverage patterns, mainly publicly insured children with uninsured parents.

What's new: Trends in health insurance type have changed over the past decade for low- and middle-income US families: private coverage and uninsurance have decreased, while discordant coverage increased.

Figure 1.

Trends in Child and Parent Full-Year Health Insurance Type, Low Income

Figure 2.

Trends in Child and Parent Full-Year Health Insurance Type, Middle Income

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics by Family Income, 1998-2011*

| Low Income (n=65,496) | Middle Income (n=33,246) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighed N | Weighted % | Unweighed N | Weighted % | |

| Child's Age | ||||

| 0-4 | 18,895 | 30.4 | 7,831 | 24.9 |

| 5-9 | 19,783 | 29.7 | 9,352 | 27.9 |

| 10-13 | 14,480 | 21.3 | 7,915 | 23.2 |

| 14-17 | 12,338 | 18.6 | 8,148 | 24.0 |

| Parent's Age | ||||

| ≤24 | 7,247 | 11.7 | 1,390 | 4.0 |

| 24-44 | 51,846 | 78.5 | 26,632 | 79.8 |

| ≥45 | 6,403 | 9.8 | 5,224 | 16.2 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 8,294 | 15.1 | 4,878 | 16.7 |

| Midwest | 10,707 | 20.2 | 7,397 | 24.5 |

| South | 26,327 | 38.9 | 11,715 | 35.5 |

| West | 20,168 | 25.9 | 9,256 | 23.3 |

| Child's Health Status^ | ||||

| Excellent/Very Good | 47,802 | 75.2 | 27,506 | 84.3 |

| Good/Fair/Poor | 17,677 | 24.8 | 5,729 | 15.7 |

| Child's Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 16,388 | 40.4 | 17,005 | 66.2 |

| Non-Hispanic, Non-White | 18,577 | 27.7 | 7,278 | 17.9 |

| Hispanic | 30,531 | 31.9 | 8,963 | 15.9 |

| Parent's Education^ | ||||

| ≥12 years | 41,201 | 71.0 | 29,929 | 93.7 |

| <12 years | 24,045 | 29.0 | 3,242 | 6.3 |

| Family composition | ||||

| One parent | 28,003 | 42.1 | 7,078 | 20.7 |

| Two parents | 37,493 | 57.9 | 26,168 | 79.4 |

| Parent's employment^ | ||||

| Employed | 49,903 | 78.3 | 32,068 | 97.1 |

| Unemployed | 15,492 | 21.7 | 1,161 | 2.9 |

Data Source: Medical Expenditure Panel - Household Survey

Weighted percentages are reported for the entire study period (1998-2011) as one pooled sample

Sample N's do not add up to total unweighted column N due to exclusion of a small number of missing responses Column percentages = approximately 100% (rounded to nearest tenth of a percent).

Note: Low Income = <200% FPL (federal poverty level); Middle Income = 200 - <400% FPL. The FPL in 2011 was $22,350.

Table 2.

Percentage of Child and Parent Full-Year Health Insurance Type by Family Income, 1998 versus 2011

| Low Income (n=65,496) | Middle Income (n=33,246) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-Year Health Insurance Type | 1998 Weighted % | 2011 Weighted % | 1998 Weighted % | 2011 Weighted % |

| Child Type/Parent(s) Type | ||||

| Private/Private | 29.2 | 19.1 | 74.5 | 66.3 |

| Private/Public | # | # | # | # |

| Private/Uninsured | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| Public/Private | 3.4 | 8.2 | 2.9* | 4.3 |

| Public/Public | 21.3 | 24.0 | 3.0 | 6.2 |

| Public/Uninsured | 10.4 | 27.2 | 1.4 | 6.7 |

| Uninsured/Private | 4.7 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 5.4 |

| Uninsured/Public | 2.1 | 1.3 | # | # |

| Uninsured/Uninsured | 26.3 | 14.8 | 13.2 | 8.7 |

| Child/Parent(s) Insurance Concordance | ||||

| Concordant^ | 76.8 | 57.9 | 90.7 | 81.2 |

| Discordant§ | 23.2 | 42.1 | 9.3 | 18.8 |

Data Source: Medical Expenditure Panel - Household Survey

Column percentages = approximately 100% (rounded to nearest tenth of a percent).

Cell sizes for the years 1998-2000 were <30; this value is from the year 2001.

Estimates not reported due to small cell sizes (n<30).

Concordant= child private/parent(s) private; child public/parent(s) public; child uninsured/parent(s) uninsured

Discordant=child private/parent(s) public; child private/parent(s) uninsured; child public/parent(s) private; child public/parent(s) uninsured; child uninsured/parent(s) private; child uninsured/parent(s) public.

Discordant=child private/parent(s) public; child private/parent(s) uninsured; child public/parent(s) private; child public/parent(s) uninsured; child uninsured/parent(s) private; child uninsured/parent(s) public.

BOLD P-value (P<0.05) considered statistically significant, calculated using chi-square tests, comparing rates in 1998 versus 2011.

Note: Low Income = <200% FPL (federal poverty level); Middle Income = 200 - <400% FPL. The FPL in 2011 was $22,350.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Yearly Percentage Point Change in Child and Parent Health Insurance Type by Family Income, 1998-2011

| Yearly Percentage Point Change (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full-year Health Insurance Type | Joinpoint Identified Trend | Unadjusted* | Adjusted^ |

| Child Type/Parent(s) Type | |||

| Low Income | |||

| Private/Private | 1998-2011 | −0.86 (−1.10, −0.63) | −0.92 (−1.12, −0.72) |

| Private/Public | # | # | # |

| Private/Uninsured | 1998-2011 | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.03) |

| Public/Private | 1998-2004 | 0.90 (0.57, 1.23) | 0.90 (0.58, 1.22) |

| 2004-2009 | −0.36 (−0.97, 0.24) | −0.35 (−0.72, 0.02) | |

| 2009-2011 | 0.94 (−0.81, 2.68) | 0.86 (−0.04, 1.75) | |

| Public/Public | 1998-2011 | 0.43 (0.26, 0.59) | 0.53 (0.27, 0.79) |

| Public/Uninsured | 1998-2003 | 1.74 (1.36, 2.12) | 1.63 (1.18, 2.08) |

| 2003-2011 | 0.98 (0.75, 1.20) | 1.00 (0.65, 1.34) | |

| Uninsured/Private | 1998-2011 | −0.15 (−0.22, −0.07) | −0.17 (−0.25, −0.09) |

| Uninsured/Public | 1998-2011 | −0.04 (−0.08, −0.01) | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.01) |

| Uninsured/Uninsured | 1998-2011 | −0.81 (−1.05, −0.58) | −0.87 (−1.07, −0.67) |

| Middle Income | |||

| Private/Private | 1998-2011 | −0.73 (−0.98, −0.48) | −0.61 (−0.83, −0.40) |

| Private/Public | # | # | # |

| Private/Uninsured | 1998-2011 | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.02) | −0.02 (−0.08, 0.03) |

| Public/Private | 2001-2011 | 0.14 (0.03, 0.24) | 0.11 (−0.03, 0.25) |

| Public/Public | 1998-2011 | 0.16 (0.06, 0.25) | 0.22 (0.10, 0.34) |

| Public/Uninsured | 1998-2011 | 0.42 (0.34, 0.51) | 0.37 (0.28, 0.47) |

| Uninsured/Private | 1998-2011 | 0.02 (−0.06, 0.11) | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.11) |

| Uninsured/Public | # | # | # |

| Uninsured/Uninsured | 1998-2004 | −0.58 (−1.01, −0.15) | −0.66 (−1.12, −0.20) |

| 2004-2007 | 1.24 (−0.96, 3.45) | 0.93 (−0.11, 1.96) | |

| 2007-2011 | −1.36 (−2.19, −0.54) | −1.39 (−2.09, −0.69) | |

Unadjusted results from joinpoint regression.

Adjusted results from multinomial logistic regression, with covariates including child's age, parent's age, race/ethnicity of the child, region of residence, parental education, family composition, parental employment, and child's perceived health status.

BOLD P-value (P<0.05) considered statistically significant.

Small sample sizes (N<30) for most years, estimates unreliable.

Note: Low Income = <200% FPL (federal poverty level); Middle Income = 200 - <400% FPL. The FPL in 2011 was $22,350.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (grant number 1 R01 HS018569), Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [(PCORI) Health Systems Cycle I (2012)], the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health, grant number (1 R01 CA181452 01), the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Family Medicine, and the Ohio State University Department of Family Medicine. The funding agencies had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. AHRQ collects and manages the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: We have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. DeVoe, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Family Medicine, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, mailcode FM, Portland, OR 97239.

Carrie J. Tillotson, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Division of Biostatistics, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, mailcode CR-145, Portland, OR 97239.

Miguel Marino, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Family Medicine, Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Division of Biostatistics, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, mailcode FM, Portland, OR 97239.

Jean O'Malley, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Division of Biostatistics, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, mailcode CR-145, Portland, OR 97239.

Heather Angier, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Family Medicine, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, mailcode FM, Portland, OR 97239, 503-349-6362.

Lorraine S. Wallace, The Ohio State University, Department of Family Medicine, 263 Northwood-High Building, 2231 North High Street, Columbus, Ohio 43201, Phone: 614-293-8007, Fax: 614-293-2715.

Rachel Gold, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Center for Health Research, 3800 N. Interstate Avenue, Portland, OR 97227-1098, Phone: 503.335.2400.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sommers BD, Baicker K, Epstein AM. Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):1025–1034. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asplin BR, Rhodes KV, Levy H. Insurance status and access to urgent ambulatory care follow-up appointments. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1248–1254. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burstin HR, Lipsitz SR, Brennan TA. Socioeconomic status and risk for substandard medical care. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2383–2387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vistnes J, Schone B. Pathways to coverage: the changing roles of public and private sources. Health Affairs. 2008;27(1):44–57. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured . The Uninsured, A Primer: Key Facts about Health Insurance on the Eve of Health Reform. The Henry J Kaiser family foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVoe J, Krois L, Edlund C, Smith J, Carlson N. Uninsurance among children whose parents are losing Medicaid coverage: results from a statewide survey of Oregon families. Health Services Research. 2008;43(1 Part II):401–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Wallace LS. Children's Receipt of Health Care Services and Family Health Insurance Patterns. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(5):406–413. doi: 10.1370/afm.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Angier H, Wallace LS. Predictors of children's health insurance coverage discontinuity in 1998 versus 2009: parental coverage continuity plays a major role. Maternal and child health journal. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVoe JE, Marino M, Angier H, et al. Effect of Expanding Medicaid for Parents on Children's Health Insurance Coverage: Lessons From the Oregon Experiment. JAMA Peds. 2015;169(1):e143145. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen RA, Makuc DM, Bernstein AB, et al. Health insurance coverage trends, 1959-2007: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. National Health Statistics reports. 2009(17):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeVoe JE, Crawford C, Angier H, et al. The Association Between Public Coverage for Children and Parents Persists: 2002-2010. Matern Child Health J. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1690-5. [epub ahead of print] 10 Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegenfuss JY, Davern ME. Twenty years of coverage: an enhanced current population survey-1989-2008. Health Services Research. 2010;46(1 Pt 1):199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berdahl TA, Friedman BS, McCormick MC, Simpson L. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: trends in racial/ethnic, income, and insurance disparities over time, 2002-2009. Academic Pediatrics. 2013;13(3):191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [February 27, 2014];Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: Household Component. 2010 http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/household.jsp.

- 16.Cohen J, Monheit A, Beauregard K, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996:373–389. Winter. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau JS, Adams SH, Park MJ, Boscardin WJ, Irwin CE., Jr. Improvement in preventive care of young adults after the affordable care act: the affordable care act is helping. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014;168(112):1101–1106. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold R, DeVoe JE, McIntire PJ, Puro JE, Chauvie SL, Shah AR. Receipt of diabetes preventive care among safety net patients associated with differing levels of insurance coverage. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2012;25(1):42–49. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson LM, Tang S-fS, Newacheck PW. Children in the United States with Discontinuous Health Insurance Coverage. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):382–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register. 1998;63(36):9235–9238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register. 2011;76(13):3637–3638. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates: correction. Stat Med. 2001;20:655. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong JR, Harris JK, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Johnson KJ. Incidence of childhood and adolescent melanoma in the United States: 1973-2009. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):846–854. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon AE, Uddin SG. National trends in primary cesarean delivery, labor attempts, and labor success, 1990-2010. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;209(6):554.e551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes RFW, Moore ML, Garfein RS, Brodine S, Strathdee SA, Rodwell TC. Trends in mortality of tuberculosis patients in the United States: the long-term perspective. Annals of Epidemiology. 2011;21(10):791–795. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill HD, Shaefer HL. Covered today, sick tomorrow? Trends and correlates of children's health insurance instability. Medical Care Research and Review. 2011;68(5):523–536. doi: 10.1177/1077558711398877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommers BD. Insuring children or insuring families: do parental and sibling coverage lead to improved retention of children in Medicaid and CHIP? Journal of Health Economics. 2006;25(6):1154–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamauchi M, Carlson MJ, Wright BJ, Angier H, Devoe JE. Does Health Insurance Continuity Among Low-income Adults Impact Their Children's Insurance Coverage? Matern Child Health J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0968-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cutler DM, Gruber J. Does Public Insurance Crowd out Private Insurance? The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1996;111(2):391–430. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gresenz CR, Edgington SE, Laugesen M, Escarce JJ. Take-up of public insurance and crowd-out of private insurance under recent CHIP expansions to higher income children. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(5):1999–2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01408.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamersma S, Kim M. Participation and crowd out: assessing the effects of parental Medicaid expansions. Journal of Health Economics. 2013;32(1):160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMorrow S, Kenney GM, Waidmann T, Anderson N. Access to Private Coverage for Children Enrolled in CHIP. Academic Pediatrics. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.02.005. [E-pub ahead of print] March 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young RA, DeVoe JE. Who Will Have Health Insurance in the Future? An Updated Projection. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:156–162. doi: 10.1370/afm.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gould E. Employer-sponsored health insurance erosion continues in 2008 and is expected to worsen. Int J Health Serv. 2010;40(4):743–776. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.4.j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured [August 3, 2011];States Respond to Fiscal Pressure: State Medicaid Spending Growth and Cost Containment in Fiscal Years 2003 and 2004. Results from a 50-State Survey. 2003 http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/States-Respond-to-Fiscal-Pressure-State-Medicaid-Spending-Growth-and-Cost-Containment.pdf.

- 37.DeVoe JE, Krois L, Edlund C, Smith J, Carlson N. Uninsured but eligible children: are their parents insured? Recent findings from Oregon. Medical Care. 2008;46(1):3–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815b97ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation . Recent Trends in Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment as of January 2015: Early Findings from the CMS Performance Indicator Project. Menlo Park, C.A.: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Data Note: How Has the Individual Insurance Market Grown Under the Affordable Care Act? Menlo Park, C.A.: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Implementing the ACA's Medicaid-Related Health Reform Provisions After the Supreme Court's Decision. 2012 Aug; [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Adults who Remained Uninsured at the End of 2014. Menlo Park, C.A.: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaiser Family Foundation [February 23, 2015];Children's Health Coverage: Medicaid, CHIP and the ACA. 2014 http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/childrens-health-coverage-medicaid-chip-and-the-aca/.

- 43.Health Policy Brief: The Family Glitch. Health Aff. 2014 Nov 10; [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selden TM, Dubay L, Miller GE, Vistnes J, Buettgens M, Kenney GM. Many Families May Face Sharply Higher Costs If Public Health Insurance For Their Children Is Rolled Back. Health Aff. 2015;34(4):697–706. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]