Figure 2. The fitted model explains the observed spiking responses, with estimated modulators that are both anatomically and functionally targeted.

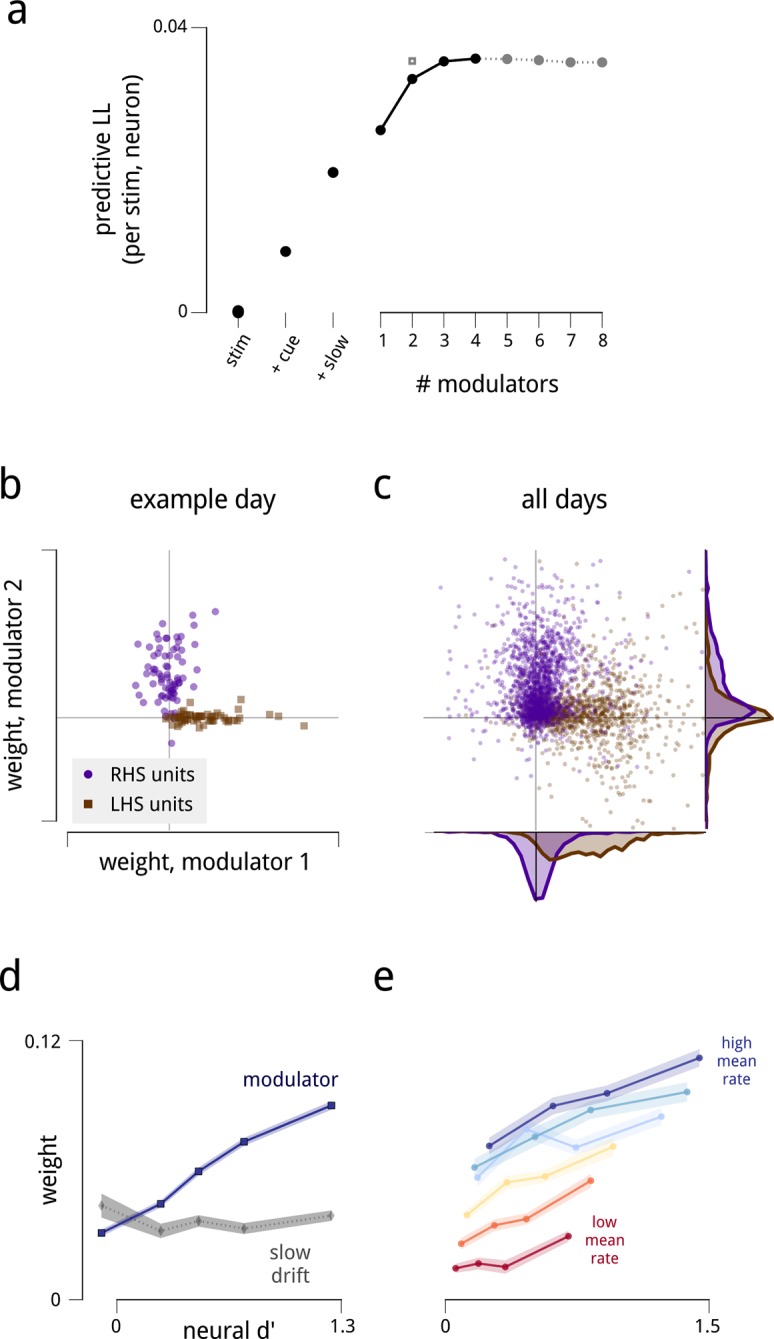

(a) Performance comparison of various submodels, measured as log-likelihood (LL) of predictions on held-out data. Values are expressed relative to performance of a stimulus-drive-only model (leftmost point), and increase as each model component (cue, slow drift, and different numbers of shared modulators) is incorporated. The grey square shows the predictive LL for a two-modulator model, with each modulator constrained to affect only one hemisphere (i.e. with coupling weights set to zero for neurons in the other hemisphere). This restricted model is used for all results from Figure 2d onwards, excepting the fine temporal analysis of Figure 6c. (b) Modulators are anatomically selective. Inferred coupling weights for a two-modulator model, fit to a population of units recorded on one day. Each point corresponds to one unit. As the model does not uniquely define the coordinate system (i.e. there is an equivalent model for any rotation of the coordinate system), we align the mean weight for LHS units to lie along the positive x-axis (see Materials and methods). (c) Distribution of inferred coupling weights aggregated over all recording days indicates that each shared modulator provides input primarily to cells in one hemisphere. (d) Hemispheric modulators are functionally selective. Units which are better able to discriminate standard and target stimuli in the cue-away condition have larger coupling weights (blue line). Discriminability is estimated as the difference in mean spike count between standard and target stimuli, divided by the square root of their average variance (d′). Values are averaged over units recorded on all days, subdivided into five groups based on their coupling weights. Shaded area denotes ±1 standard error. Pearson correlation over all units is r = 0.42. This relationship is not seen for the weights that couple neurons to the slow global drift signal (gray line, Pearson correlation r = 0.00). The relationship between d′ and cue weight is significant, but weaker than for modulator weight (r = 0.24); this is not shown here as the cue weights are differently scaled. (e) Same as in (d), but with units subdivided into subgroups according to mean firing rate. Each line represents a subpopulation of ∼500 units with similar firing rates (from red to blue: 0–7; 7–12; 12–17; 17–25; 25–35; 35–107 spikes/s). Within each group, the Pearson correlations between d′ and coupling weight are between 0.2–0.3, but the correlations between mean rate and coupling weight are weak or negligible.

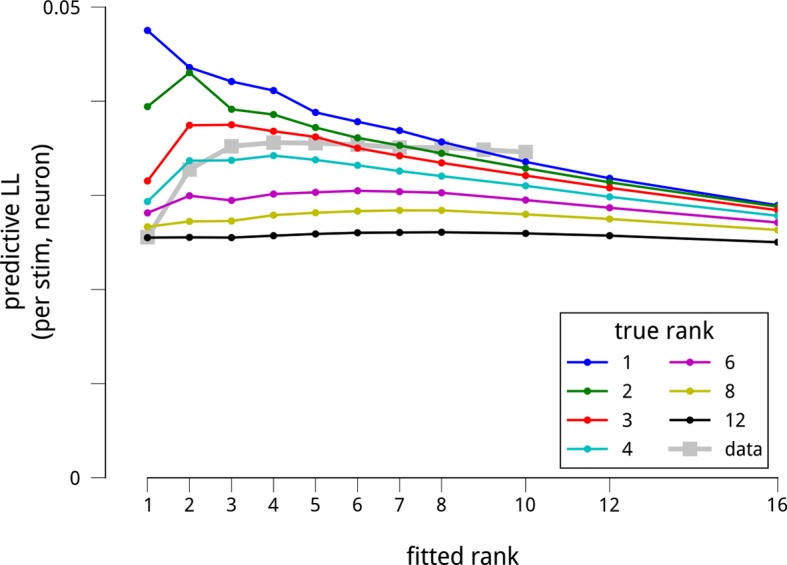

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. The dataset is sufficient to support the estimation of up to 8 shared modulators.

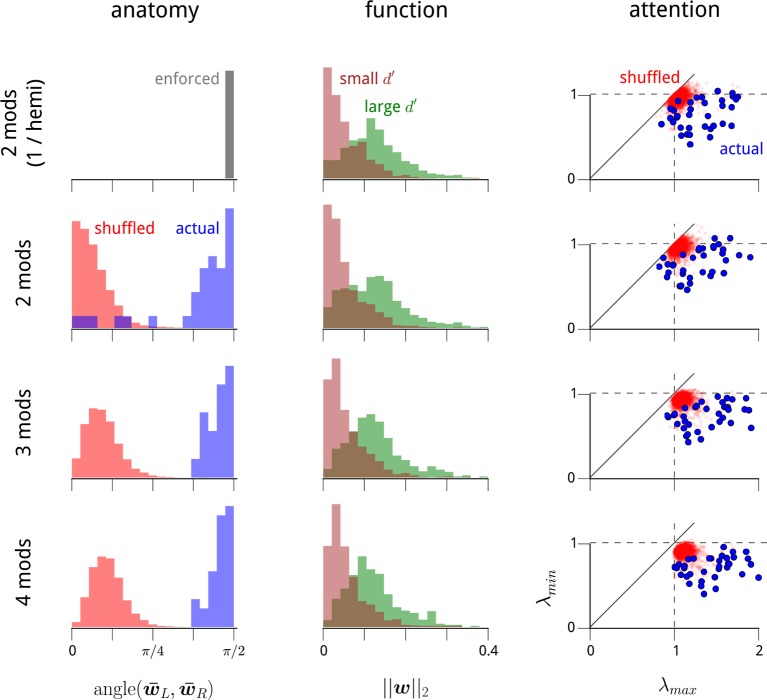

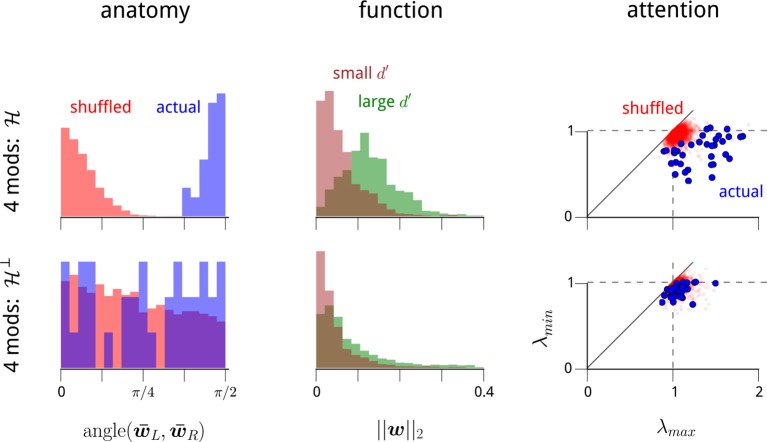

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. The structure of the modulators in higher-dimensional modulator models.

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. The modulators' anatomical, functional, and attentional structure manifests primarily within the dominant two dimensions of modulation.

Figure 2—figure supplement 4. Units with higher mean firing rates typically had stronger coupling to their respective population modulator (r2 = 0.21).