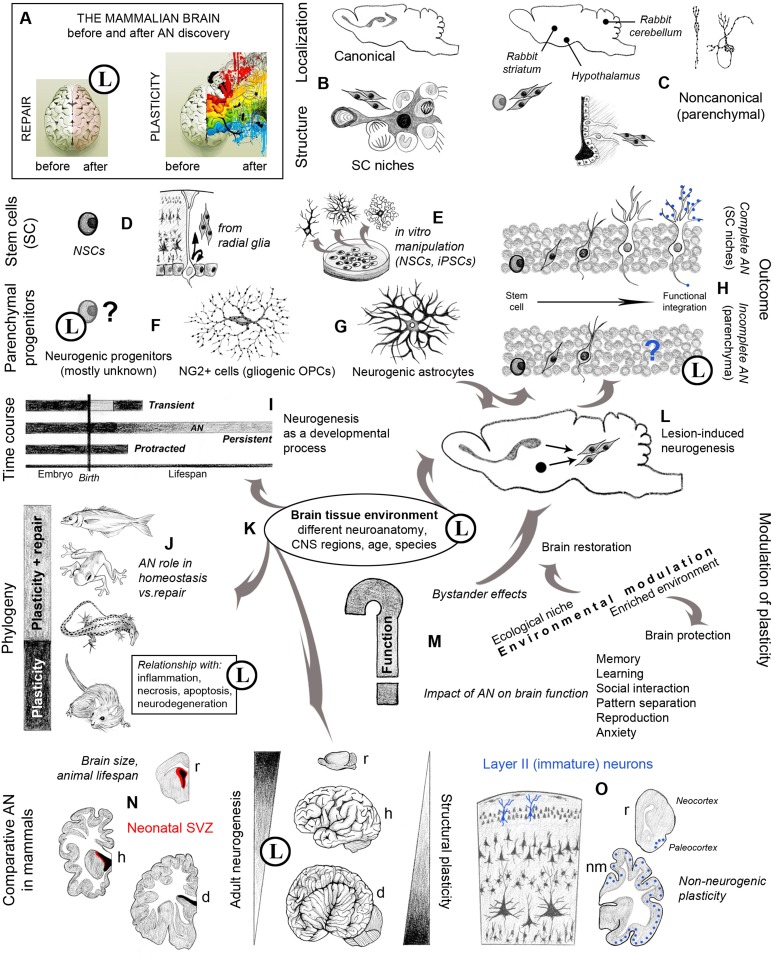

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of multifaceted aspects and new opportunities arisen in neurobiology by the study of adult neurogenesis (AN). Circled L indicate when substantial limits are also present. (A) An image originally referring to brain hemisphere asymmetry (http://thebiointernet.org/training-of-right-brain-hemisphere-and-intuitive-information-sight-in-bratislava/) is used here to represent the new vision of brain plasticity after AN discoveries; beside remarkable limits still existing in brain repair (pale pink), most opportunities involve new forms of structural plasticity with respect to the old dogma of a static brain (rainbow colors). (B) Canonical sites of AN, harboring well characterized stem cell niches (Tong and Alvarez-Buylla, 2014; Vadodaria and Gage, 2014). (C) Different types and locations of non-canonical neurogenesis do occur in various brain regions, depending on the species (Luzzati et al., 2006; Ponti et al., 2008; Feliciano et al., 2015). (D) NSCs are astrocytes originating from bipotent radial glia cells (Kriegstein and Alvarez-Buylla, 2009); (E) the occurrence of stem cells in the brain gives rise to (theoretically endless) in vitro manipulations. (F) Parenchymal progenitors are less known; most of them are gliogenic, yet some are responsible for species-specific/region-specific, non-canonical neurogenesis, and some others can be activated after lesion (G) (Nishiyama et al., 2009; Feliciano et al., 2015; Nato et al., 2015). (H) The outcome of canonical and non-canonical neurogenesis is different, only the former leading to functional integration of the newborn neurons (Bonfanti and Peretto, 2011); blue dots: synaptic contacts between the new neurons and the pre-existing neural circuits. (I) Strictly speaking, AN should be restricted to the continuous, “persistent” genesis of new neurons, which is different from “protracted” neurogenesis (delayed developmental processes, e.g., postnatal genesis of cerebellar granule cells, postnatal streams of neuroblasts directed to the cortex; Luzzati et al., 2003; Ponti et al., 2006, 2008), and “transient” genesis of neuronal populations within restricted temporal windows (e.g., striatal neurogenesis in guinea pig; Luzzati et al., 2014). (L) Reactive neurogenesis can be observed in different injury/disease states both as a cell mobilization from neurogenic sites and as a local activation of parenchymal progenitors (Arvidsson et al., 2002; Magnusson et al., 2014; Nato et al., 2015). (J) Evolutionary constraints have dramatically reduced the reparative role of AN, involving tissue reactions far more deleterious than in non-mammalian vertebrates (Weil et al., 2008; Bonfanti, 2011). (K) Failure in mammalian CNS repair/regeneration is likely linked to mature tissue environment, clearly refractory to new neuron integration outside the two canonical NSC niches and relative neural systems; this fact confines AN to physiological/homeostatic roles, which remain undefined in terms of “function.” (M) The role of AN strictly depends on the animal species, evolutionary history and ecological niche; its rate and outcome is affected by different internal and external cues; although not being strictly a function, AN can impact several brain functions (Voss et al., 2013; Aimone et al., 2014; Amrein, 2015). (N) Different anatomy, physiology, and lifespan in mammals do affect AN rate and outcome; periventricular AN is highly reduced in large-brained mammals (Sanai et al., 2011; Paredes et al., 2015; Parolisi et al., 2015). (O) Studies on AN carried out by using markers of immaturity (e.g., DCX and PSA-NCAM) have revealed other forms of plasticity (non-neurogenic), being well represented in large-brained mammals (Gomez-Climent et al., 2008; Bonfanti and Nacher, 2012). r, rodents; h, humans; d, dolphins; nm, non-rodent mammals. Drawings by the Author.