Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of cleaning methods to remove zinc oxide-eugenol-based root canal sealer (Endomethasone) on the bond strength of the self-etching adhesive to dentin.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty crowns of bovine incisors were cut to expose the pulp chamber. A zinc oxide- and eugenol-based sealer was placed for 10 min in contact with the pulp chamber dentin. Specimens were divided into four groups according to the cleaning method of dentin used: G1, no root canal sealer (control); G2, 0.9% sodium chlorite (NaCl); G3, ethanol; and G4, followed by diamond drill. After cleaning, the teeth were restored with composite resin and Clearfil SE Bond. All specimens were sectioned to produce rectangular sticks and dentin/resin interface was submitted to microtensile bond testing. The mean bond strengths were analyzed using ANOVA/Tukey (α = 0.05).

Results:

G3 and G4 showed bond strengths similar to the G1 (P > 0.05). A significant decrease in the bond strength in the G2 was observed (P < 0.05). G1, G3, and G4, the predominant failure mode was the mixed type. The prevalence of adhesive failure mode was verified in the G2.

Conclusion:

The cleaning methods affected the bond strength of the self-etching adhesive to dentin differently.

Keywords: Composite resins, dentin bonding agents, endodontics

INTRODUCTION

A major goal of endodontic therapy is to eliminate bacteria from the root canal system to create an environment that is most favorable for healing.[1] This is achieved through mechanical cleaning and shaping as well as irrigation with antibacterial agents.[2,3] Furthermore, the restoration of endodontically treated teeth is very important for clinical success.[4] The purpose of the restoration of endodontically treated teeth is to prevent bacteria leakage from the oral cavity, to withstand occlusal force, to be esthetic, and to prevent fracture of the remaining tooth structures.[5] Weine[6] indicated that improper restoration leads to loss of endodontically treated teeth more than an actual failure of endodontic therapy. Vire[7] verified that 59.4% of the failures in teeth submitted to root canal treatment occur during re-establishment of the lost dental structure.

Endodontically treated teeth with a sufficient amount of sound coronal structure can be restored with composite resin by the direct technique, because of its capacity to bond to dentin.[8,9,10] This technique relies on an adhesive system via micromechanical interlocking with a hybrid layer[9] and by the potential to reinforce the weakened tooth structure.[5] This process requires the appropriate interaction of the adhesive system with the dentin substrate. However, the irrigating substances[8,9,10] and root canal sealers[11,12,13,14] frequently used during endodontic treatment could interfere in the bond strength of the adhesive materials to dentin. The presence of eugenol in the sealer used in the filling can interfere with the polymerization of the adhesive system, reducing the microtensile bond strength. Studies have evaluated the effect of root canal sealers and their compounds on the retention of intraradicular posts, and the results have shown a decrease in the retention of posts fixed by resin cements in canals filled with a root canal sealer containing eugenol.[11,12,13,14] In addition, root canal sealer residue left in the coronal portion is one of the factors responsible for the darkening of the tooth crown.[15]

Since the importance of bond strength right after the conclusion of endodontic treatment has already been established, the aim of this study was to investigate the influence of cleaning methods to remove zinc oxide-eugenol-based root canal sealer (Endomethasone) on the bond strength of the self-etching adhesive to dentin. It is hypothesized that these different cleaning methods have an affect on the resin-dentin bond strength.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Twenty bovine incisors were stored in 0.5% thymol and used within 2 months of extraction. The teeth were cut to expose the pulp chamber dentine of the middle third of the buccal crown: 5 mm was removed horizontally from the incisal portion of the crown with a double-sided diamond disc (KG Sorensen, Barueri, SP, Brazil) under refrigeration. Next, the middle third of the crown was removed at a height of approximately 8 mm corresponding to the double-sided diamond disc radius (KG Sorensen, Barueri, SP, Brazil), which then penetrated into the middle third of the incisal edge parallel to the long axis of the tooth, removing the buccal surface of the crown fragment. Once the samples were obtained, the pulp tissue was carefully removed with a spoon excavator. After the cuts, the intracoronary dentin was polished for 30 s with wet 180- and 600-grit silicon carbide abrasive paper under running water to plane and create a standardize smear layer. Then, the samples were rinsed with distilled water and dried with paper points. Twenty customized rectangular dentin fragments were obtained.

The Endomethasone N (Septodont, Saint-Maur-Dês-Fossés, France) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and placed for 10 min in contact with the pulp chamber dentin of each sample. Specimens were divided into four groups, with five specimens in each group., according to the method of cleaning dentin used. G1, no root canal sealer was placed on dentin (control); G2, cotton pellets saturated with 0.9% sodium chlorite (NaCl); G3, cotton pellets saturated with 70% ethanol; G4, cotton pellets saturated with NaCl followed by diamond drill removing 250 μm dentin. The cleaning was performed until all the root canal sealer on the dentin was removed when viewed through an optical microscope under ×10 magnification. Before bonding procedures, all teeth were irrigated with 5 mL of physiologic solution dried with absorbent paper. A self-etching adhesive system, Clearfil SE Bond (Kuraray, Kurashiki, Japan), was applied to the surface of the pulp chamber dentin according to the manufacturer's instructions. Three layers of a resin composite (B0.5, Z250; 3M ESPE, St Paul, MN) were added to the bonded dentin, and each one was light cured for 40 s using a halogen light-curing unit operated at 600 mw/cm2 (Demetron Res Corp., Danbury, CT). After composite filling of dentin, the teeth were stored in distilled water at 37°C.

After 24 h, specimens were removed from water, dried, and fixed to an acrylic plate to allow the creation of serial cross-sections using a diamond saw (Buehler Ltd). Twenty rectangular sticks were obtained from each group from the central portion of the crown segment to assure the presence of a linear resin/dentin interface. The sticks were individually attached to a testing apparatus, with cyanoacrylate adhesive (Loctite Adesivos, Itapevi, Brazil) and subjected to a tensile load (EMIC DL 2000, São José dos Pinhais, Brazil) at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min until failure.

The failure modes were examined under ×20 magnification with a stereoscope (Lambda Let 2 - ATTO Instruments Co., Hong Kong, China) and ImageLab 2.3 software (University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil) and classified into one of four types: Adhesive (interfacial failure), adhesive/cohesive (mixed), cohesive in resin, and cohesive in dentin. For each group, two dentin slices were obtained, and were not used for the bond strength measurements. The specimens were sputter-coated with gold in a Denton Vacuum Desk II Sputtering device (Denton Vacuum, Cherry Hill, USA) and observed by scanning electron microscopy (JSM/5600 LV - JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Thus, the interfacial micromorphology also was observed.

The microtensile bond strengths were determined and analyzed using analysis of variance and the Tukey test for post-hoc comparisons (α = 0.05) using the BioEstat 2.0 program (CNPq 2000, Brasília, Brazil).

RESULTS

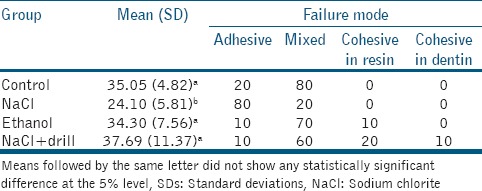

The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. The statistical analysis of the data revealed significant differences between the groups (P < 0.05). Cleaning with NaCl provided significantly lower bond strength to dentin (P < 0.05). Conversely, experimental groups cleaned with ethanol or NaCl followed by drill tended to express bond strength values similar to that observed for the control group (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Bond strength mean and SDs (in MPa) and failure mode (%) according to experimental groups

Table 1 shows the failure modes observed in each group. In the control group and ethanol or NaCl followed by the drill, the predominant failures were mixed. In the cleaning with NaCl group, the adhesive between the resin and dentin was most frequently observed.

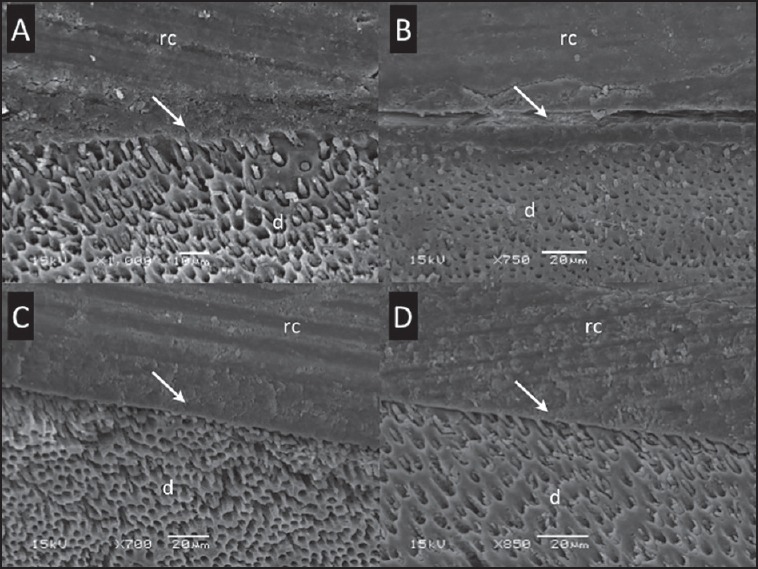

On the basis of scanning electron microscopic analysis, the interfacial micromorphology between the self-etch adhesive system and dentin is shown in Figure 1. All groups exhibited few resin tags between the self-etch adhesive and the dentin. The hybrid layer observations revealed similar patterns and good adaption between the G1, G3 and G4, except for G2 that showed spaces between the hybrid layer and dentin.

Figure 1.

A representative scanning electron microscopic photomicrograph of the interface between self-etch adhesive system and coronal dentin to all groups. (a) No root canal sealer (control group); (b) Cleaning with sodium chlorite; (c) G3, cleaning with ethanol; and (d) G4, cleaning with sodium chlorite followed by drill. Arrow indicates the hybrid layer. d: Dentin, rc: Resin composite

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that the group cleaned with cotton pellets with NaCl had significantly lower bond strength of the self-etching adhesive to dentin compared to the other groups, confirming the hypothesis under study. These results suggest that cleaning of the dentin with NaCl is ineffective to provide a surface suitable for application of the self-etching adhesive used in the study. Previous studies have shown that endodontic sealers present low solubility in water.[16,17] Remains of filling material may have remained in the dentin. Several studies have determined that eugenol-based sealers decrease the bond strength of adhesive materials.[11,12,13,14] Eugenol residues remaining on the dentin might interfere with the polymerization of adhesive resins and because of their interdiffusion through dentin, they can cause a significant reduction in the adhesive effectiveness or even modify the polymerized resin surface[12] and decrease the bond strength of the resinous materials. Markowitz et al.[18] reported that a chelating reaction occurs when zinc oxide is mixed with eugenol, resulting in grains of zinc oxide absorbed in a zinc eugenolate matrix, which makes it impossible for the eugenol to be released. However, because of the presence of fluids inside dentinal tubules, this reaction becomes reversible; the eugenol released then penetrates the dentin and tends to become concentrated at the tooth-adhesive interface.[12]

After completion of the root canal filling procedure, cleaning the pulp chamber with an alcohol-based solution is generally recommended.[17] The results of this study indicate that the ethanol-cleaning group had similar bond strength of the self-etching adhesive to dentin compared with the control group. These results suggest that cleaning was effective and resulted in adequate bond strength. Some studies have shown that eugenol-based sealers exhibit higher solubility than resin- and calcium-hydroxide-based cements.[17,19] This factor may have favored the removal of sealer residue from the dentin surface. Tjan and Nemetz[20] demonstrated a substantial decrease in retention of posts luted with resin cement in the presence of eugenol. However, irrigation with ethanol or etching with 37% phosphoric acid gel was found to be effective in restoring the resistance to dislodgment of the posts, but alcohol produced the most consistent and reliable results.

Dentin matrix is mainly composed of type I collagen and noncollagenous proteins.[21] Because these fibrils are intrinsically wet because of their high affinity to water, the adhesive components are more prone to degradation over time because of water sorption, resin leaching, and other water-mediated aging phenomena that weaken the polymer structure of the adhesive and lead to the failure of the adhesive interface.[22] For this reason, recent findings have indicated that the more the adhesive blends are hydrophobic, the more the bonds are stable over time. Because ethanol can replace water from dentin, hydrophobic monomers are able to penetrate the dentin and form a more stable hybrid layer.[22,23] Recent studies have also revealed that the adhesive blends containing water-based solvents (such as Clearfil SE Bond) could jeopardize the adhesive interface as a result of phase separation and/or inadequate solvent evaporation.[23] Cecchin et al.[24] revealed that an ethanol application can be used to improve the self-etching adhesive durability for 12 months of anatomic posts to root dentin when using self-etching Clearfil SE Bond. The reasonable explanation of the improved bonding ability of this self-etching adhesive system to ethanol-saturated root dentin is related to the ability of ethanol to accelerate the dentin water substitution rate, thereby reducing the intrinsic wetness of the root canal at the same time.[22]

The removal of the residual root canal sealer to dentin seems to be fundamental for the adhesion process.[25,26] The results of this study show that the removing of the dentin surface containing endodontic sealer with a drill resulted in high bond-strength values to dentin, similar to the control group. However, our study showed that dentin cleaning containing sealer eugenol using ethanol is sufficient to obtain high bond-strength values. Therefore, it is not necessary to use drills, to reduce the loss of healthy dental structure. Moreover, removal of the dental structure on cavity preparation has a direct correlation with the decrease in the resistance to fracture. It is well-known that the reduction of tooth resistance to fracture is proportional to the increase in cavity size, especially when marginal ridges are removed.[27]

Regarding the fracture analysis, it should be emphasized that the predominant types of failure in the NaCl cleaning group were adhesion between resin and dentin, implying that the weak link was the bond between resin and dentin. Therefore, some sealer components might have remained and interfered with effective dentin bonding. The quality of the bond the other groups appeared to be superior because the predominant type of failure was the mixed type. This suggests that the bond between the resin and dentin was less affected than the group when NaCl cleaning [Table 1 and Figure 1].

The ability to achieve excellent esthetic results, improvements in composite mechanical/physical properties, as well as the development adhesive systems that allow for more conservative restorative techniques, contributed to the enhanced performance of composite resins.[28,29] Therefore, restoration of endodontically treated teeth with these materials can be performed when the remaining tooth structures are enough.[8,10] Moreover, restoration with self-etching adhesives and composites may offer some advantages. Self-etching adhesives have weak acids in their primer composition that can completely dissolve or disperse smear layers resulting in less change in the dentinal wall structure than the strong acids of total-etch systems. In addition, once primer application is performed without air-drying, collapse of collagen fibrils is avoided, reducing technique-sensitivity.[9,30]

Therefore, endodontic therapy and restoration of endodontically treated teeth cannot be regarded as separate entities. The adaptation of restorative materials to dentin is an extremely important factor and may lead to more predictable endodontic treatment outcomes. Several aspects, however, need further research. The possible interactions between the resin-based sealer and other methods of dentin cleaning on the bond strength of self-etch and total-etch adhesive systems should be analyzed in future studies.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study, the cleaning methods affected the bond strength of the self-etching adhesive to dentin differently.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by FAPESP grant protocol 2011/06026-7.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças IN. Clinical implications and microbiology of bacterial persistence after treatment procedures. J Endod. 2008;34:1291–1301.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zehnder M. Root canal irrigants. J Endod. 2006;32:389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu LS, Kim JR, Ling J, Choi KK, Pashley DH, Tay FR. Review of contemporary irrigant agitation techniques and devices. J Endod. 2009;35:791–804. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ray HA, Trope M. Periapical status of endodontically treated teeth in relation to the technical quality of the root filling and the coronal restoration. Int Endod J. 1995;28:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1995.tb00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausiello P, De Gee AJ, Rengo S, Davidson CL. Fracture resistance of endodontically-treated premolars adhesively restored. Am J Dent. 1997;10:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weine FS. Nonsurgical re-treatment of endodontic failures. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1995;16(324):326–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vire DE. Failure of endodontically treated teeth: Classification and evaluation. J Endod. 1991;17:338–42. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farina AP, Cecchin D, Barbizam JV, Carlini-Júnior B. Influence of endodontic irrigants on bond strength of a self-etching adhesive. Aust Endod J. 2011;37:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2010.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz RS. Adhesive dentistry and endodontics. Part 2: Bonding in the root canal system-the promise and the problems: A review. J Endod. 2006;32:1125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos JN, Carrilho MR, De Goes MF, Zaia AA, Gomes BP, Souza-Filho FJ, et al. Effect of chemical irrigants on the bond strength of a self-etching adhesive to pulp chamber dentin. J Endod. 2006;32:1088–90. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen BI, Volovich Y, Musikant BL, Deutsch AS. The effects of eugenol and epoxy-resin on the strength of a hybrid composite resin. J Endod. 2002;28:79–82. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldissara P, Zicari F, Valandro LF, Scotti R. Effect of root canal treatments on quartz fiber posts bonding to root dentin. J Endod. 2006;32:985–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demiryürek EO, Külünk S, Yüksel G, Saraç D, Bulucu B. Effects of three canal sealers on bond strength of a fiber post. J Endod. 2010;36:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cecchin D, Farina AP, Souza MA, Carlini-Júnior B, Ferraz CC. Effect of root canal sealers on bond strength of fibreglass posts cemented with self-adhesive resin cements. Int Endod J. 2011;44:314–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plotino G, Buono L, Grande NM, Pameijer CH, Somma F. Nonvital tooth bleaching: A review of the literature and clinical procedures. J Endod. 2008;34:394–407. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan AE, Goldberg F, Artaza LP, de Silvio A, Macchi RL. Disintegration of endodontic cements in water. J Endod. 1997;23:439–41. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly A, Sword J, Nishitani Y, Yoshiyama M, Agee K, Tay FR, et al. Water sorption and solubility of methacrylate resin-based root canal sealers. J Endod. 2007;33:990–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markowitz K, Moynihan M, Liu M, Kim S. Biologic properties of eugenol and zinc oxide-eugenol. A clinically oriented review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:729–37. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90020-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho-Junior JR, Correr-Sobrinho L, Correr AB, Sinhoreti MA, Consani S, Sousa-Neto MD. Solubility and dimensional change after setting of root canal sealers: A proposal for smaller dimensions of test samples. J Endod. 2007;33:1110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjan AH, Nemetz H. Effect of eugenol-containing endodontic sealer on retention of prefabricated posts luted with adhesive composite resin cement. Quintessence Int. 1992;23:839–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tay FR, Pashley DH. Have dentin adhesives become too hydrophilic? J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:726–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Ruggeri A, Cadenaro M, Di Lenarda R, De Stefano Dorigo E. Dental adhesion review: Aging and stability of the bonded interface. Dent Mater. 2008;24:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Carvalho RM, Rueggeberg FA, Agee KA, Carrilho M, et al. From dry bonding to water-wet bonding to ethanol-wet bonding. A review of the interactions between dentin matrix and solvated resins using a macromodel of the hybrid layer. Am J Dent. 2007;20:7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cecchin D, de Almeida JF, Gomes BP, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC. Effect of chlorhexidine and ethanol on the durability of the adhesion of the fiber post relined with resin composite to the root canal. J Endod. 2011;37:678–83. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts S, Kim JR, Gu LS, Kim YK, Mitchell QM, Pashley DH, et al. The efficacy of different sealer removal protocols on bonding of self-etching adhesives to AH plus-contaminated dentin. J Endod. 2009;35:563–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuga MC, Só MV, De Faria-júnior NB, Keine KC, Faria G, Fabricio S, et al. Persistence of resinous cement residues in dentin treated with different chemical removal protocols. Microsc Res Tech. 2012;75:982–5. doi: 10.1002/jemt.22023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de V Habekost L, Camacho GB, Azevedo EC, Demarco FF. Fracture resistance of thermal cycled and endodontically treated premolars with adhesive restorations. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98:186–92. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varvara G, Perinetti G, Di Iorio D, Murmura G, Caputi S. In vitro evaluation of fracture resistance and failure mode of internally restored endodontically treated maxillary incisors with differing heights of residual dentin. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98:365–72. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerdolle DA, Mortier E, Droz D. Microleakage and polymerization shrinkage of various polymer restorative materials. J Dent Child (Chic) 2008;75:125–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frankenberger R, Perdigão J, Rosa BT, Lopes M. “No-bottle” vs “multi-bottle” dentin adhesives — A microtensile bond strength and morphological study. Dent Mater. 2001;17:373–80. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(00)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]