Abstract

Accurate estimates of spatio-temporal resolved near-surface air temperature (Ta) are crucial for environmental epidemiological studies. However, values of Ta are conventionally obtained from weather stations, which have limited spatial coverage. Satellite surface temperature (Ts) measurements offer the possibility of local exposure estimates across large domains. The Southeastern United States has different climatic conditions, more small water bodies and wetlands, and greater humidity in contrast to other regions, which add to the challenge of modeling air temperature. In this study, we incorporated satellite Ts to estimate high resolution (1 km × 1 km) daily Ta across the southeastern USA for 2000-2014. We calibrated Ts to Ta measurements using mixed linear models, land use, and separate slopes for each day. A high out-of-sample cross-validated R2 of 0.952 indicated excellent model performance. When satellite Ts were unavailable, linear regression on nearby monitors and spatio-temporal smoothing was used to estimate Ta. The daily Ta estimations were compared to the NASA's Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA) model. A good agreement with an R2 of 0.969 and a mean squared prediction error (RMSPE) of 1.376 °C was achieved. Our results demonstrate that Ta can be reliably predicted using this Ts-based prediction model, even in a large geographical area with topography and weather patterns varying considerably.

Keywords: Air temperature, Surface temperature, MODIS, reanalysis, Exposure error

1. Introduction

Global warming adds urgency to better understand the impact of temperature on health, particularly in the warm areas such as the southeastern USA. Growing evidence has linked near-surface air temperature (Ta), an important environmental stressor, with morbidity and mortality (1-7). Previous studies concerning human health and Ta exposure are primarily limited by the spatial and temporal availability of Ta measurements, leaving large areas uncovered. Temperature can vary greatly both in space and time, therefore these collected point-samples are insufficient to adequately capture the spatial and temporal variability within a large area (8). In addition, owing to the urban heat-island effect, higher temperatures are often observed in urban areas versus surrounding areas. For example, temperatures measured in a station near an airport may underestimate the true near-surface air temperatures in the urban area.

However, these small geographic changes in air temperature can have important health effects. Shi et al. (2015) found that both geographical contrasts and annual anomalies of local air temperature contribute to excess public health burden of climate change (9). They used daily local air temperature estimates at fine geographic scale (1 km × 1 km) in New England, to capture the exposure variability in space and time which may be driving the adverse health effects. Lower exposure measurement errors, and the inclusion of the entire region, largely alleviate the downward bias in health effect estimates.

In recent years, several methods were developed to address the lack of high-resolution exposure data. Geospatial statistical methods, such as land use regression and kriging, are most commonly used approaches. They allow characterizing the spatial heterogeneity of exposure by using time invariant geographical variables to expand the ground monitored measurements to large areas (10, 11). However these methods do not generally capture temporal variability in exposure, in that they are commonly based on a year of intensive monitoring, and miss changes over years in the spatial pattern of Ta. Therefore they are primarily used to assess chronic health effects.

Satellite-based remote sensing can provide additional information at high spatial and temporal resolution. Satellite instruments, such as Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), can provide global daily estimates of 1 km surface skin temperature (Ts), the temperature at the air-soil interface (12-14). Ts is derived from the thermal infrared signal received by the satellite sensor. Ts as an indicator of the net surface energy balance, depends on the presence of vegetation or plant cover, atmospheric conditions, and thermal properties of the underlying surfaces. It is different from Ta, which is measured at meteorological stations at the screen height of 1-2 m above the land surface.

Several studies have shown that Ts and Ta are correlated (15, 16). Even so, there are many factors that can influence the complex and geographically heterogeneous relationship between Ts and Ta, such as humidity, the type of underlying surfaces, the elevation, and other surface parameters. Additionally, Dousset (17) stated that Ta has superior correlation with Ts at night because the solar radiation does not affect the thermal infrared signal. During nighttime Ts is close to Ta and during daytime Ts is generally higher than Ta (12).

The value of Ta cannot be predicted by Ts using a simple linear relationship with reasonable accuracy. Fu et al. (2011) explored predicting Ta using satellite Ts and found an R2>0.55 (18). Recently, Kloog et al. (2014) presented a novel model and assessed daily mean Ta in the northeastern USA using MODIS-derived Ts measurements (19, 20). Better predictive performance was reported. For days with available Ts data, mean out-of-sample R2 was 0.947. Even for days without Ts values, the model accuracy was also excellent. Although Ta estimation in the northeastern USA was excellent, it is uncertain that how well the satellite approach would perform in areas with different geographic features and weather patterns.

Predicting Ta for the southeastern USA is of top priority for epidemiological studies. Many researchers are of great interest in investigating the health effects of temperature using the Medicare cohort (aged 65+), because this elderly population is potentially most vulnerable to climate change. Due to its warm weather, the southeastern USA contains a very large Medicare population (13 millions). Thus, it is particularly urgent to provide a comprehensive temperature dataset for this particular region.

The aim of this paper was to estimate 15-year daily local air temperature in the southeastern USA, by extending and validating the previous hybrid-model approach to account for the unique geographical and climatological characteristics of the study area. Specifically, by incorporating satellite derived Ts, Ta measured at monitors, meteorological variables and land use terms, we employed a 3-stage statistical modeling approach to obtain daily air temperature predictions at 1 km × 1 km resolution across the southeastern USA for the years 2000-2014. The retrieved air temperature was cross validated against the measurements from weather stations. As an independent validation, the results were also compared with NASA's reanalysis products, Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study domain

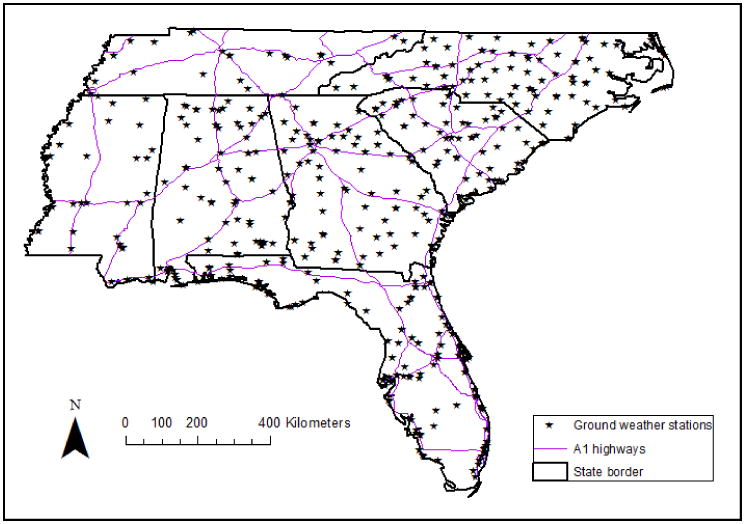

The spatial domain of our study includes the southeastern part of the USA, comprising the states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Florida (Fig. 1). The southeastern states include some populous metropolitan areas (Charlotte, Memphis, Raleigh, Atlanta and Miami), rural towns, large forested regions, mountains, water bodies, and the Atlantic sea shoreline. The study region covers an area of 916,904 km2 with a population of 56,742,948 according to the 2010 census (UCSB, 2010), and encompasses 1,013,408 discrete 1 km × 1 km satellite grid cells.

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area showing all available NCDC air temperature monitor stations across southeastern USA for 2000-2014.

2.2 Surface temperature

Daily Ts data from the MODIS sensors located on polar orbiting Terra satellite for the years 2000-2014, with a spatial resolution of 1 km × 1 km were used to prepare the analysis presented in this paper. They were calculated from land surface temperature (LST) and emissivity using the formula Ts =LST/Emissivity1/4. These MOD11_A1 products (LST & emissivity) are freely available online through the NASA website (NASA, 2014), and cover tiles h10v05, h10v06, and h11v05. They include the latitude and longitude of 1 km grid cell centroid, nighttime and daytime LST, and emissivity.

Nighttime Ts was observed to have a higher correlation with air temperature (r = 0.94), compared to daytime Ts (r = 0.87). This is consistent with previous literature, demonstrating that the nighttime Ts generally present superior correlations with ground measurements of Ta across most sites in the USA. More details about MODIS Ts data can be found in the literature (19, 21).

2.3 Meteorological data from weather stations

In our analysis, daily data for Ta from weather stations across the southeastern USA (see Fig. 1) for 2000-2014 were obtained from the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC). There were 538 NCDC stations operating daily in the southeastern USA during the study period. The mean Ta across the study area during the study period was 18.59 °C with a standard deviation of 7.96 °C and an interquatile range (IQR) of 12.28 °C.

2.4 NDVI

The presence of vegetation on the surface can also affect Ts, since incoming solar radiation is partly intercepted by vegetative surfaces during the day, and part of the outgoing longwave radiation at night is also intercepted by vegetation. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data were available at 1 km resolution from the monthly MODIS product (MOD13A3). Monthly vegetation index was used as NDVI values have little within-month variation and the spatial distribution is illustrated in the Appendix A (Fig. A.1). To create the covariate of NDVI for daily Ts. the distances between centroids of NDVI and that of a grid cell of Ts were calculated, and the nearest NDVI value of the current month was merged.

2.5 Spatial predictors of air temperature

To enhance the predictive ability of the final model, we included the following statistically significant spatial predictors in the models, which influence Ts or Ta and thereby modify the relationship between Ts and Ta. These time-invariant variables were first processed into 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution (details are described below). Spatial distributions for these variables are illustrated in the Appendix A (Fig. A.2 – Fig. A.4). For the daily dataset, spatial predictors were assigned to the nearest grid cell for each day, and these data served as covariates for the daily surface temperature.

2.5.1 Percent of urban areas

In urban areas, residential, commercial and industrial developments often produce radical changes in radiative, thermodynamic and aerodynamic characteristics of the surface. Thus the associated Ts are often modified substantially. Percent of urban areas data were obtained from the 2011 national land cover data (NLCD) (22). Data were available as raster files with a 30 m spatial resolution. We reclassified the raster into 0 (open space) and 1 (urban areas), by recoding land cover codes 22, 23, 24 (sub categories for developed areas) to 1 as an urban cell and assigning 0 for the remaining. The mean of the 30 m-resolution binary values within each 1 km grid cell was calculated, namely percent of urban areas.

2.5.2 Elevation

There are notable elevation contrasts across such a large area, thus elevation was used as a spatial predictor. Generally, higher elevations are associated with lower air temperatures. Elevation data were obtained from the National Elevation Dataset (23). NED data is available from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and provides elevation data covering the Unite States at a spatial resolution of 1 arc second (30 m). The mean of the 30 m-resolution elevation values within each 1 km grid cell was calculated and used as a spatial predictor.

2.5.3 Distance to water body

The presence of moisture at the surface greatly moderates the diurnal range of surface temperatures, due to the increased evaporation from the surface and increased heat capacity of water. Over a free water body, about 80% of the net radiation is utilized for evaporation on average and the ground heat flux is reduced. We used the Esri Data and Maps for ArcGIS 2013 for water body data. We created a dummy variable taking the value of 1, if the 1 km grid cell centroid is on water and 0 otherwise. The distance from centroids to water body (a continuous measure) was also calculated, which equals to 0 if the centroid is on water.

2.6 Statistical methods

Data preparation was implemented using MATLAB (R2014b, MathWorks), and all modeling was done using the R statistical software. The prediction process consists of 3 stages. The stage 1 model calibrates the Ts - Ta relationship on each day during 2000-2014 using data from grid cells with both ground Ta monitors and Ts measurements. We performed daily calibrations with nighttime MODIS Ts for the reasons noted earlier. The base model (stage 1), fit to data from each year (2000-2014) separately, consists of a mixed model with day-specific random effects to capture the day-to-day variation in the Ts - Ta relationship. Specifically the base model can be written as:

(uj vj) ∼N[(0 0), Σ]

where Taij denotes the measured mean air temperature at a spatial site i on a day j; α and uj are the fixed and random (day-specific) intercepts, respectively, Tsij is the surface temperature value in the grid cell corresponding to site i on a day j; β1 and vj are the fixed and random slopes, respectively. Elevationi is the mean elevation in the grid cell corresponding to site i, NDVIik is the monthly NDVI value in the grid cell corresponding to site i for the month in which day j falls, percent urbani is the percent of urban area in the grid cell, distance to water bodyi is the distance of the grid cell to the nearest water body, and water bodyi is a 0/1 dummy variable identifying grid cells that intersect water polygons. Finally, Σ is an unstructured variance-covariance matrix for the random effects and εij is the error term at site i on a day j.

The performance of the base model was validated by 10-fold cross-validation. The dataset was randomly divided into 90% and 10% splits ten times. We fit the model using 90% of the data, and then use this model to predict for the held-out 10% of the data. Then the “out-of-sample” cross-validated (CV) R2 were computed. To check for bias, we regressed the measured Ta values in the held-out data against the predicted values in each site on each day. We assessed the model prediction performance by taking the square root of the mean squared prediction errors (RMSPE). Overall temporal R2 and overall spatial R2 were calculated as well. More details are provided in Kloog et al. (20).

In stage 2, we predicted Ta in grid cells without monitors but with available Ts measurements using the stage 1 model coefficients. This is implemented by simply applying the estimated prediction model fit obtained from stage 1 to these additional Ts values. This resulted in datasets with Ta predictions for all available Ts cell/day combinations.

To impute data for grid cells/days for which Ts measurements were not available, the stage 3 model was fitted by using the stage 2 predictions. Specifically, for each grid cell, we regressed the Ta predictions obtained from stage 2 on the daily mean measured Ta (from the stations within a 100 km buffer of that grid cell), land use terms and a smooth nonparametric function of latitude and longitude of the grid cell centroid, with random cell-specific intercepts and slopes. This is similar to universal kriging, by using Ta measurements from nearby grid cells to help fill in the missing. We selected a 100 km buffer size because it was small enough to ensure relevance and large enough to include multiple Ta stations to produce more stable estimates. Because the spatial patterns of Ta vary temporally, a separate spatial surface was fit for each two-month period. This approach provides additional information about the Ta in the missing grid cells that simple kriging would not. Specifically, the following semiparametric regression model was fitted:

(uj vj) ∼ [(0 0), Ωβ)]

where PredTaij is the predicted air temperature at a grid cell i on a day j from the mixed model; mTaij is the mean Ta in the relevant 100 km buffer for cell i on a day j; α and uj are the fixed and random intercepts, respectively; β1 and vi are the fixed and random slopes, respectively. NDVIik is the monthly NDVI value in the grid cell corresponding to site i for the month in which day j falls, percent urbani is the percent of urban area in the grid cell, and distance to water bodyi is the distance of the grid cell to nearest water body. The smooth (X,Y) is a thin plate spline fit to the latitude and longitude of the centroid of grid cell i, k(j) denotes the two-month period in which day j falls (that is, a separate spatial smooth was fit for each two-month period).

The calculated coefficients of the stage 3 model would then be used to fill in the missing Ta values. In contrast to stage 2, the stage 3 model includes cell-specific random intercepts and slopes, which allows for temporal and spatial interpolation for each grid cell. That is, we could use the random effects for a grid cell to help impute Ta data of this cell for days when Ts measurements were unavailable. If grid cells did not have any temperature monitors within their 100 km buffer, no temperature was imputed. Such locations were generally in unpopulated areas.

2.7 Validation against reanalysis data

MERRA is a NASA reanalysis dataset generated using the version 5.2.0 of the Goddard Earth Observing System (GEOS-5) atmospheric data assimilation system. Reanalysis is a technique for generating a comprehensive meteorological record by assimulating observations from multiple platforms using numerical models. Different from the statistical approach used in this study, the models used in reanalysis are based on physical rules of atmospheric motions. The reanalysis datasets are widely used for analysis of long term, large scale climatic changes. Their spatial resolution, however, is usually coarse (24). Although reanalysis may also utilize some of the observations, such as the weather station data and satellite irradiance, which are also used in the statistical modeling, it represents an entirely different modeling approach and its results can be considered as an independent source of information for validation purpose.

In this study, the MERRA daily air temperature at 2 m above displacement height (T2m) was chosen to validate the retrieved Ta. MERRA data has a coarser spatial resolution of 1/2° × 2/3° in latitude/longitude. The 1 km grids of retrieved Ta were matched with the nearest MERRA grid centroid. A MERRA grid can contain 3000 to 4300 of such 1 km grids. These grids were aggregated and averaged by day, and the averaged data were used for validation. For some MERRA grids which contain both land and ocean pixels, the number of matched 1 km grids can be less, because our statistical model only retrieves air temperature above the land. To avoid interference of ocean pixels, MERRA with less than 1878 (lowest 15th percentile) 1 km grids matched were removed from analysis.

3 Results

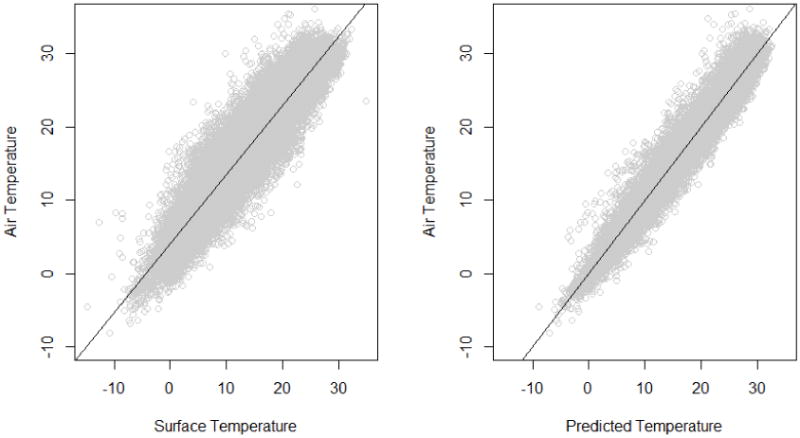

The correlation between the satellite-derived Ts and the Ta obtained from the monitor sites within the same grid cells was high, indicating that Ts can provide useful information for predicting Ta. As an example, results for the year 2011 are shown in Fig. 2 (left). An R2 value of 0.89 indicates that although Ts and Ta are highly correlated, there are still some variations of Ta cannot be explained by Ts without the calibration using more predictors. Other factors, such as elevation, NDVI, and land use terms can also affect the Ta - Ts relationship. Their correlations with Ta and Ts are shown as well (see Table A.1 and A.2). Taking those factors into account, the relationship between the predicted Ta from our daily calibration method and the monitored Ta is greatly improved (e.g., R2=0.96 in 2011). Effect estimates for stage 1 are reported in Appendix A (Table A.3).

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots of the monitored air temperature versus satellite surface temperature (left) and the monitored air temperature versus that from the stage 1 calibration (right). Data are shown for the year 2011.

For the stage 1 calibration, we conducted a 10-fold cross-validation. The results of 10-fold cross-validation, which can represent the out-of-sample performance of our stage 1 model, are presented in Table 1. For the entire study period, the mean out-of-sample R2 was 0.952 (year-to-year variation 0.935 -0.962). The spatial and temporal R2 values (mean of 0.867 and 0.961, respectively) also showed good performance of the model. We found no bias in our cross-validation results (slope of observed versus predicted = 1.00). The model also yielded small prediction errors, with an RMSPE of 1.662 °C and spatial RMSPE of 0.903 °C. All of these indicated excellent model performance. To show the heterogeneity of the model performance, the results of 10-fold cross-validation for each state for the year 2011 are reported in Appendix A (Table A.4).

Table 1. Prediction accuracy in Stage 1: 10-fold cross-validated (CV) R2 for daily Ta predictions (2000-2014).

| Year | CV R2 | CV R2Spatial | CV R2Temporal | RMSPE | RMSPESpatial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 0.941 | 0.804 | 0.955 | 1.74 | 1.071 |

| 2001 | 0.937 | 0.860 | 0.948 | 1.796 | 0.973 |

| 2002 | 0.962 | 0.888 | 0.970 | 1.530 | 0.871 |

| 2003 | 0.944 | 0.840 | 0.955 | 1.753 | 0.942 |

| 2004 | 0.943 | 0.858 | 0.953 | 1.804 | 0.938 |

| 2005 | 0.960 | 0.854 | 0.971 | 1.541 | 0.888 |

| 2006 | 0.935 | 0.792 | 0.942 | 1.920 | 0.977 |

| 2007 | 0.957 | 0.834 | 0.967 | 1.544 | 0.924 |

| 2008 | 0.950 | 0.891 | 0.958 | 1.738 | 0.848 |

| 2009 | 0.950 | 0.875 | 0.958 | 1.812 | 0.897 |

| 2010 | 0.960 | 0.917 | 0.969 | 1.709 | 0.871 |

| 2011 | 0.962 | 0.901 | 0.970 | 1.487 | 0.878 |

| 2012 | 0.959 | 0.890 | 0.967 | 1.458 | 0.810 |

| 2013 | 0.960 | 0.919 | 0.965 | 1.562 | 0.826 |

| 2014 | 0.962 | 0.888 | 0.970 | 1.530 | 0.827 |

|

| |||||

| Overall Mean | 0.952 | 0.867 | 0.961 | 1.662 | 0.903 |

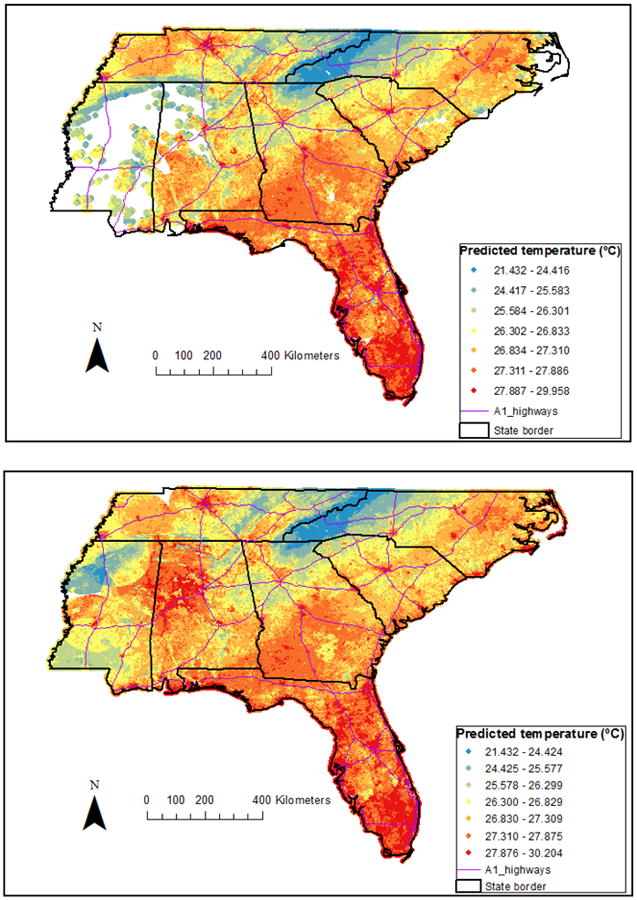

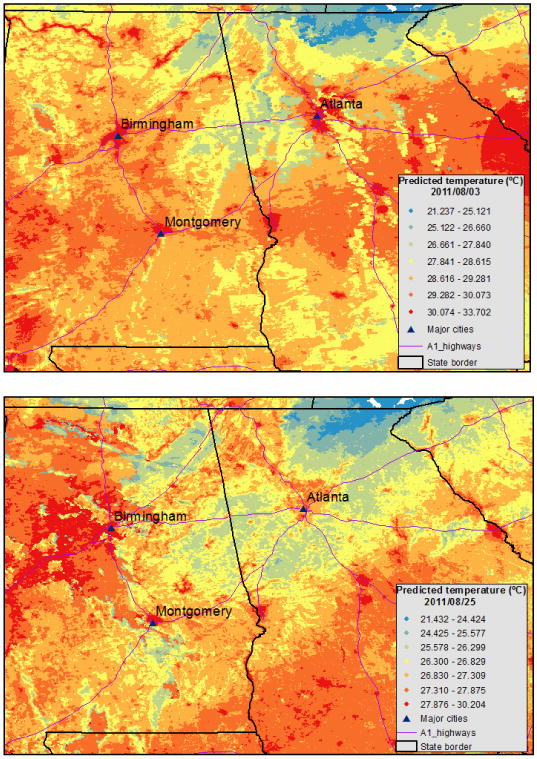

In stage 2, we used the parameters derived from stage 1 model to predict Ta in grid cells without monitors but with available Ts measurements. Fig. 3 (top) presents the spatial pattern of predicted Ta values from stage 2 at 1 km × 1 km resolution, on a sample day (2011.08.25). It can be seen that there are a considerable number of grid cells with missing values, because of the missing satellite data, typically because of cloud cover. For the entire 15 years, stage 2 contributed to 42.4% of the final Ta predictions.

Fig. 3.

Predicted air temperature (°C) from stage 2 (top) and both stage 2 & 3 (bottom) in each 1 km × 1 km grid on a sample day (2011.08.25) across the southeastern USA.

The missing values of stage 2 can be filled using a stage 3 model, and the results are shown in Fig. 3 (bottom). The stage 3 model also performed well. The R2 values between stage 3 and stage 2 predictions are shown in Appendix A (Table A.5), and the mean R2 value for the entire study period is 0.971 (year-to-year variation 0.962 - 0.981). For the entire 15 years, 56.2% of the final predictions were derived from stage 3. There was still a small amount of missing predictions (1.4%) due to lack of monitored Ta measurements within 100 km buffer on a day. More details are in Table 2.

Table 2. Contribution of each stage for the daily Ta predictions for each year (2000-2014).

| Year | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 38.1% | 60.4% | 1.5% |

| 2001 | 39.4% | 59.2% | 1.4% |

| 2002 | 37.7% | 60.9% | 1.4% |

| 2003 | 39.4% | 59.1% | 1.5% |

| 2004 | 38.2% | 60.6% | 1.2% |

| 2005 | 44.3% | 54.6% | 1.1% |

| 2006 | 47.2% | 51.7% | 1.1% |

| 2007 | 45.7% | 53.2% | 1.1% |

| 2008 | 46.3% | 52.6% | 1.1% |

| 2009 | 41.0% | 57.9% | 1.1% |

| 2010 | 46.2% | 52.2% | 1.6% |

| 2011 | 48.0% | 50.0% | 2.0% |

| 2012 | 45.2% | 52.9% | 1.9% |

| 2013 | 39.0% | 59.7% | 1.3% |

| 2014 | 40.3% | 58.6% | 1.1% |

|

| |||

| Overall Mean | 42.4% | 56.2% | 1.4% |

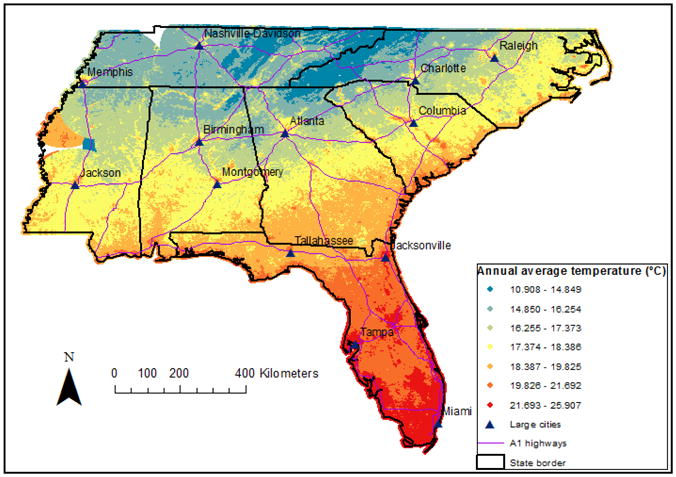

Figure 4 illustrates the spatial pattern of estimated Ta values from the 3-stage statistical models, averaged over the year of 2011 for the southeastern USA area. In the calculation of the annual average, we removed grid cells with less than 243 observations (2/3 of the daily Ta predictions) in 2011. After restriction, estimated annual average Ta values across the study area for 2011 ranged from 10.91 °C to 25.91 °C. The figure shows that urban areas such as Raleigh, Atlanta, Birmingham, Jackson, Columbia, and Memphis, appear warmer than the surrounding areas possibly due to urban heat-island effect (25). In addition, estimated annual Ta values are higher in areas closer to the shoreline compared with inland areas as an impact of the ocean.

Fig. 4.

Spatial pattern of predicted air temperature (°C), averaged over the 2011 for the southeastern USA.

In addition to the spatial variability we observed, air temperature showed temporal variation in its spatial pattern as well. Figure 5 shows that there is space-time variation in the estimated Ta values for a subset of the study area. The results indicate that our model predictions can well resolve the day-to-day variation in the spatial pattern of Ta exposure.

Fig. 5.

Predicted air temperature (°C) at a 1 km × 1 km grid for August 3, 2011 (top) and August 25, 2011 (bottom).

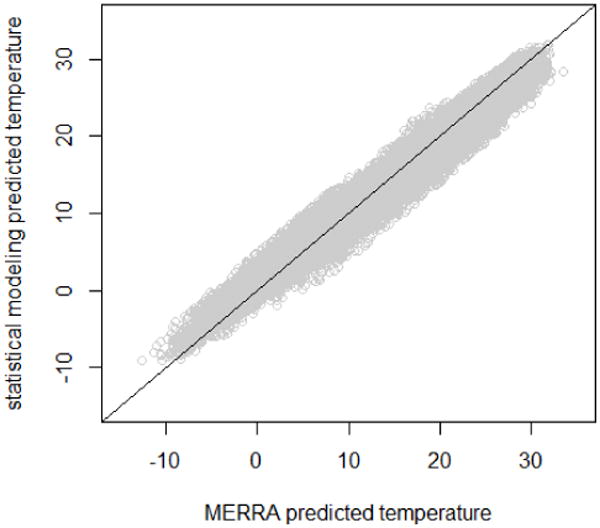

With respect to the final Ta exposure dataset that we generated, an independent validation was performed, by comparing our final daily Ta dataset with MERRA products T2m. A good agreement was achieved, with an overall R2 of 0.969 and RMSPE of 1.376 °C. The spatial and temporal R2 values are 0.954 and 0.976, respectively. Results for the year 2011 are shown in Fig. 6 as an example. Comparison results for 15 years are compiled in Table 3.

Fig. 6.

A scatter plot of the calculated daily average Ta versus the daily T2m from MERRA. Data are shown for the year 2011.

Table 3. Prediction accuracy: R2 for comparing final daily Ta predictions with MERRA products (2000-2014).

| Year | CV R2 | CV R2Spatial | CV R2Temporal | RMSPE | RMSPESpatial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 0.959 | 0.896 | 0.970 | 1.553 | 1.375 |

| 2001 | 0.964 | 0.955 | 0.972 | 1.388 | 1.095 |

| 2002 | 0.972 | 0.966 | 0.978 | 1.344 | 0.846 |

| 2003 | 0.974 | 0.958 | 0.981 | 1.245 | 0.876 |

| 2004 | 0.969 | 0.956 | 0.978 | 1.356 | 0.979 |

| 2005 | 0.971 | 0.955 | 0.979 | 1.328 | 0.871 |

| 2006 | 0.960 | 0.952 | 0.970 | 1.487 | 1.261 |

| 2007 | 0.965 | 0.951 | 0.971 | 1.456 | 1.154 |

| 2008 | 0.968 | 0.964 | 0.974 | 1.389 | 0.942 |

| 2009 | 0.971 | 0.965 | 0.981 | 1.342 | 0.970 |

| 2010 | 0.978 | 0.953 | 0.984 | 1.361 | 0.840 |

| 2011 | 0.969 | 0.964 | 0.976 | 1.423 | 0.969 |

| 2012 | 0.964 | 0.960 | 0.971 | 1.341 | 0.981 |

| 2013 | 0.972 | 0.965 | 0.980 | 1.288 | 0.960 |

| 2014 | 0.974 | 0.956 | 0.979 | 1.336 | 0.892 |

|

| |||||

| Overall Mean | 0.969 | 0.954 | 0.976 | 1.376 | 1.001 |

4 Discussion

The southeastern USA is distinguished by its warm weather and serves as a place for relocation, particularly for the elderly who are most sensitive to climate change. The rapid population growth further urges epidemiological studies on the health effects of climate change in this area. Most temperature-related epidemiological studies have relied on central meteorological stations to assess Ta. The poor spatial resolution of monitor stations can result in exposure measurement error, with expected downward bias in estimating the health effects of temperature and elevated risk of not finding a significant association. This has been recently demonstrated in a study of temperature and birth weight in Massachusetts (27). As a result, recently increasing epidemiological studies have used the finer scale exposure estimates from remote sensing (28-30).

To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first study estimating spatially and temporally resolved air temperature for the southeastern USA with a humid subtropical climate. We presented several key features in our study. First, the Ta prediction models exhibited excellent model performances. We had no bias in the cross-validation results (average slope of 1.00). In contrast to the previous work by Kloog et al (2014) in the northeastern USA, we fit a more complex model for stage 3, which included important land use terms such as proximity to water, urbanization, and time varying covariates such as NDVI. Consequently, our stage 3 model had a higher R2 (0.971) than was observed in the previous work (0.940). The results also compared well with reanalysis products, which were generated using an entirely different approach from statistical modeling.

Another key feature is that this study provides local temperature estimates on a daily basis within a study area for 15 years. Such a large 15-year daily exposure dataset will be particularly valuable for estimating the health effects of temperature in both short- and long-term, and locations outside of metropolitan areas, which are rarely included in epidemiology studies of temperature. In sum, our analysis showed that regardless of the quantity or quality of predictions, Ta can be reliably predicted from Ts if modeled appropriately.

Despite the high accuracy and low percent of missing of our model prediction, there are several limitations in the present study. For one the southeastern USA has many wetlands (swamps), which is part of the challenge of retrieving satellite Ts information. Even though 1 km is the finest resolution of Ts products that are available, Sabrino and coauthors reported that spatial resolutions lower than 50 m would underestimate the urban heat-island effect (31). In addition, this satellite-based approach still depends on ground Ta monitors. Without sufficient Ta monitors, the predictive power might be reduced dramatically, especially the mixed linear model. Because the mixed linear model uses a daily calibration method, thus requires relatively densely distributed daily Ta stations. In addition to ground Ta monitors, this satellite-based approach is also affected by some other factors, such as atmospheric conditions. Furthermore, daytime and nighttime temperatures detected by satellite are not daily mean temperatures. As a caveat, the Ta retrieved from this study should be considered as a high-resolution alternative for those areas with limited meteorological stations but cannot replace ground monitoring temperature.

In summary, we demonstrate how satellite-derived surface temperature can be used reliably to construct a high resolution dataset of daily air temperature. This dataset could well resolve and capture the spatial and temporal variations in Ta in warm areas. Public health burden of these variations should be investigated in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High resolution (1 km) daily air temperature was retrieved in Southeastern US.

Validations were conducted against weather stations and reanalysis.

High correlation and low bias were achieved.

Data are especially useful for public health studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Harvard EPA PM Clean Air Research Center (CLARC) (R-834798), and the R21 climate grants ES020695 and ES024012. The authors also thank Yara Abu Awad and Moyra Woodward for revising the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no actual or potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gosling SN, Lowe JA, McGregor GR, Pelling M, Malamud BD. Associations between elevated atmospheric temperature and human mortality: a critical review of the literature. Climatic Change. 2009;92(3-4):299–341. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gosling SN, McGregor GR, Lowe JA. Climate change and heat-related mortality in six cities Part 2: climate model evaluation and projected impacts from changes in the mean and variability of temperature with climate change. International journal of biometeorology. 2009;53(1):31–51. doi: 10.1007/s00484-008-0189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Temperature and mortality in nine US cities. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2008;19(4):563–570. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816d652d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medina-Ramón M, Schwartz J. Temperature, temperature extremes, and mortality: a study of acclimatisation and effect modification in 50 US cities. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2007;64(12):827–833. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.033175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality: a review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environ Health. 2009;8(1):40–52. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laaidi M, Laaidi K, Besancenot JP. Temperature-related mortality in France, a comparison between regions with different climates from the perspective of global warming. International journal of biometeorology. 2006;51(2):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s00484-006-0045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Z, Etzel RA, Su H, Huang C, Guo Y, Tong S. Impact of ambient temperature on children's health: a systematic review. Environmental research. 2012;117:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Y, Barnett AG, Tong S. Spatiotemporal model or time series model for assessing city-wide temperature effects on mortality? Environmental research. 2013;120:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Kloog I, Zanobetti A, Liu P, Schwartz JD. Impacts of temperature and its variability on mortality in New England. Nature Climate Change. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nclimate2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vicente Serrano SM, Sánchez S, Cuadrat JM. Comparative analysis of interpolation methods in the middle Ebro Valley (Spain): application to annual precipitation and temperature. Climate Research. 2003;24(2):161–180. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson G, Wackernagel H. Mapping temperature using kriging with external drift: theory and an example from Scotland. International journal of Climatology. 1994;14(1):77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vancutsem C, Ceccato P, Dinku T, Connor SJ. Evaluation of MODIS land surface temperature data to estimate air temperature in different ecosystems over Africa. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2010;114(2):449–465. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu W, Lű A, Jia S. Estimation of daily maximum and minimum air temperature using MODIS land surface temperature products. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2013;130:62–73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benali A, Carvalho A, Nunes J, Carvalhais N, Santos A. Estimating air surface temperature in Portugal using MODIS LST data. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2012;124:108–121. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoll MJ, Brazel AJ. Surface-air temperature relationships in the urban environment of Phoenix, Arizona. Physical Geography. 1992;13(2):160–179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voogt JA, Oke TR. Complete urban surface temperatures. Journal of Applied Meteorology. 1997;36(9):1117–1132. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dousset B, editor. AVHRR-derived cloudiness and surface temperature patterns over the Los Angeles area and their relationships to land use; Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 1989 IGARSS'89 12th Canadian Symposium on Remote Sensing, 1989 International; 1989; IEEE; [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu G, Shen Z, Zhang X, Shi P, Zhang Y, Wu J. Estimating air temperature of an alpine meadow on the Northern Tibetan Plateau using MODIS land surface temperature. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2011;31(1):8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloog I, Chudnovsky A, Koutrakis P, Schwartz J. Temporal and spatial assessments of minimum air temperature using satellite surface temperature measurements in Massachusetts, USA. Science of the Total Environment. 2012;432:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kloog I, Nordio F, Coull BA, Schwartz J. Predicting spatiotemporal mean air temperature using MODIS satellite surface temperature measurements across the Northeastern USA. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2014;150:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan Z. New refinements and validation of the MODIS land-surface temperature/emissivity products. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2008;112(1):59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin S, Yang L, Danielson P, Homer C, Fry J, Xian G. A comprehensive change detection method for updating the National Land Cover Database to circa 2011. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2013;132:159–175. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maune DF. Digital elevation model technologies and applications: the DEM users manual. Asprs Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rienecker MM, Suarez MJ, Gelaro R, Todling R, Bacmeister J, Liu E, et al. MERRA: NASA's Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications. Journal of climate. 2011;24(14):3624–3648. doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HH. Urban heat island. International Journal of Remote Sensing. 1992;13(12):2319–2336. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Y, Punnasiri K, Tong S, Aydin D, Feychting M. Effects of temperature on mortality in Chiang Mai city, Thailand: a time series study. Environ Health. 2012;11(36):10–1186. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kloog I, Melly SJ, Coull BA, Nordio F, Schwartz JD. Environmental health perspectives. 2015. Using Satellite-Based Spatiotemporal Resolved Air Temperature Exposure to Study the Association between Ambient Air Temperature and Birth Outcomes in Massachusetts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laaidi M, Zeghnoun A, Dousset B, Bretin P, Vandentorren S, Giraudet E, et al. The impact of heat islands on mortality in Paris during the August 2003 heat wave. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(2):254–259. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z, Liu Y, Ma Z, Li S, Hu W, Tong S. Impact of temperature on childhood pneumonia estimated from satellite remote sensing. Environmental research. 2014;132:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Z, Liu Y, Ma Z, Toloo GS, Hu W, Tong S. Assessment of the temperature effect on childhood diarrhea using satellite imagery. Scientific reports. 2014;4:5389. doi: 10.1038/srep05389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobrino J, Oltra-Carrió R, Sòria G, Bianchi R, Paganini M. Impact of spatial resolution and satellite overpass time on evaluation of the surface urban heat island effects. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2012;117:50–56. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.