Abstract

As the global population and its demand for seafood increases more of our fish will come from aquaculture. Farmed Atlantic salmon are a global commodity and, as an oily fish, contain a rich source of the health promoting long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic (EPA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) acids. Replacing the traditional finite marine ingredients, fishmeal and fish oil, in farmed salmon diets with sustainable alternatives of terrestrial origin, devoid of EPA and DHA, presents a significant challenge for the aquaculture industry. By comparing the fatty acid composition of over 3,000 Scottish Atlantic salmon farmed between 2006 and 2015, we find that terrestrial fatty acids have significantly increased alongside a decrease in EPA and DHA levels. Consequently, the nutritional value of the final product is compromised requiring double portion sizes, as compared to 2006, in order to satisfy recommended EPA + DHA intake levels endorsed by health advisory organisations. Nevertheless, farmed Scottish salmon still delivers more EPA + DHA than most other fish species and all terrestrial livestock. Our findings highlight the global shortfall of EPA and DHA and the implications this has for the human consumer and examines the potential of microalgae and genetically modified crops as future sources of these important fatty acids.

Omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids are widely recognised as being essential nutrients for the health and well-being of humans, particularly with respect to the n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA), eicosapentaenoic (EPA; 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic (DHA; 22:6n-3) acids, that exert a range of health benefits through their molecular, cellular and physiological actions1. Fish are the major dietary source of n-3 LC-PUFA for humans as well as being an excellent source of protein, vitamin and minerals2. Recommendations for the suggested daily intake levels of EPA and DHA vary globally, depending on the regional scientific or health advisory organisations3. Nevertheless, most agree that the general population should be consuming at least two portions of fish per week, one of which should be oily3,4,5,6,7,8. However, with the global population and its demand for seafood increasing coupled with wild catch fisheries at, or beyond, exploitable limits, a greater proportion of fish destined for the table market are being farmed. Indeed, aquaculture has been the fastest growing animal-food producing sector for the past few decades, outpacing population growth, and currently supplies around 50% of the world’s fish and seafood for human consumption9.

Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) represents an increasingly popular species in the global fish market, largely due to its high market value over low-value freshwater species. Today, salmon farming occurs throughout the world, with the main producers being Norway, Chile, Scotland and North America with a combined production volume of around 2 million metric tonnes10. Scottish salmon in particular is highly regarded throughout the world and has traditionally been marketed as a premium product, being the first fish and non-French food to receive the prestigious Label Rouge accolade in 1992 as well as being designated Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) by the European Commission in 200411,12. Accordingly, farmed Scottish salmon was the UK’s most exported food product in 2014 generating an export value of around £500 million GBP (~$789M USD) with the USA, France and emerging markets in the Far East, namely China, being the main importers13. Despite the prospective role that aquaculture can play in feeding the ever-growing population, there is increasing concern over the impact that this fast-growing industry could have on wild fish stocks14,15,16,17,18,19.

As an oily fish, Atlantic salmon provide a high nutritional content to consumers, especially with respect to EPA and DHA. However, like humans, salmon along with other coldwater marine species of fish are inefficient at converting the shorter-chain fatty acid, α-linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3n-3), into EPA and DHA, and must therefore obtain the n-3 LC-PUFA through the diet2,16,20. Farmed salmon were traditionally fed a diet with high levels of the marine ingredients, fish oil and fishmeal, derived from pelagic fisheries. The continued pressures on wild fish stocks as aquaculture production grows along with greater competition for LC-PUFA sources from the nutraceutical and pharmaceutical industries have resulted in changes to aquaculture feed formulations. Terrestrial ingredients such as plant sources, mainly of oilseed origin, are increasingly used in salmon feeds without any detriment to fish health or growth21. Nevertheless, the fatty acid profiles of vegetable oils differ from those of fish oil, being richer in n-6 PUFA and devoid of n-3 LC-PUFA, resulting in changes to the fatty acid composition of farmed fish16,21,22,23. Consequently, the nutritional benefit to the final human consumer is lowered prompting the International Fish Meal and Fish Oil Organisation, the trade group representing the marine ingredients industry, to highlight their concerns over the declining levels of n-3 LC-PUFA in farmed salmon. Thus, we examined the changes in the fatty acid contents and compositions, particularly with respect to EPA and DHA, in the flesh of Scottish Atlantic salmon farmed between 2006 and 2015 and discuss the potential implications for the human consumer.

Results and Discussion

From marine- to plant-based feeds

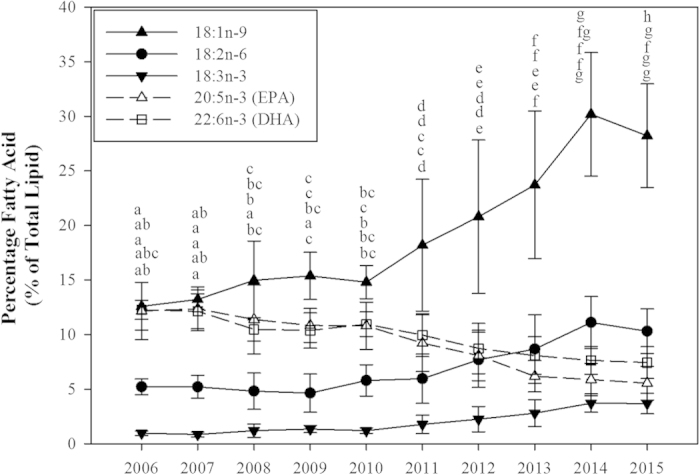

The main nutritional issue for marine finfish aquaculture has been the sourcing of sustainable alternative ingredients to replace the finite and highly exploited marine resources, fish oil and fishmeal. The development of modern, sustainable feeds with increased use of terrestrial ingredients, mainly of oilseed origin, has had no major effect on salmon health or growth performance21 and has resulted in a concomitant decrease in the levels of undesirable contaminants (e.g. dioxins and PCBs) in salmon flesh24. Nonetheless, the change in dietary oil source presents a problem for the aquaculture industry as the fatty acid composition of fish muscle (flesh) reflects that of the diet20. Rapeseed oil is the most commonly utilised fish oil alternative in Europe, including Scotland, due to its favourable price and ready availability. However, while plant-based alternatives including rapeseed contain some types of n-3 fatty acids they lack the nutritionally beneficial n-3 LC-PUFA, EPA and DHA, found almost exclusively in fish oil and other marine sources (see Table 1). Consequently, the use of rapeseed oil in aquafeeds has resulted in increased levels of ‘terrestrial’ fatty acids such as oleic (18:1n-9), linoleic (18:2n-6) and, to a lesser extent, α-linolenic (18:3n-3). This trend is evident in the fatty acid profiles of farmed Scottish salmon and is particularly noticeable from 2010 onwards when the levels of ‘terrestrial’ fatty acids showed a greater rate of change, doubling from 15%, 5% and 2% in 2010 to ~30%, 10% and 5% in 2015 (18:1n-9, 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3, respectively), while the marine fatty acids, EPA and DHA, fell by approximately half (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The increased inclusion level of plant ingredients in salmon feeds accelerated with increased fish oil prices from 2009 brought about by the growing demand for this finite resource. This has led to similar changes in salmon compositions to that in Scotland being reported in both the Norwegian and Tasmanian salmon industries25,26, reflecting the changes in salmonid feed formulations throughout the years.

Table 1. Examples of differences in fatty acid compositions of various oil sources of either terrestrial or marine origin.

| Terrestrial |

Marine |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapeseed | Soyabean | Sunflower | Linseed | Borage | Camelina | Fish Oila | Fish Oilb | Algal Oilc | Algal Oild | |

| Fatty acid (% of total lipid) | ||||||||||

| 14:0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 1.1 |

| 16:0 | 4.7 | 11.4 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 11.0 | 5.1 | 18.0 | 13.8 | 37.9 | 16.1 |

| 18:0 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| 20:0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Total saturates1 | 7.7 | 16.5 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 15.1 | 9.9 | 29.9 | 23.6 | 44.1 | 20.2 |

| 16:1n-7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 8.9 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 18:1n-9 | 62.4 | 27.4 | 28.2 | 18.7 | 16.1 | 17.4 | 7.7 | 9.7 | 0.5 | 26.9 |

| 18:1n-7 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 20:1n-9 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 4.0 | 14.2 | 1.1 | 11.6 | – | – |

| 22:1n-11 | – | – | 0.1 | – | – | – | 0.9 | 17.3 | – | – |

| 22:1n-9 | 0.1 | – | – | – | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 1.2- | – | – |

| 24:1n-9 | 0.4 | – | – | – | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Total monoenes2 | 67.5 | 29.6 | 29.5 | 19.8 | 25.1 | 36.4 | 22.8 | 49.0 | 1.3 | 28.0 |

| 18:2n-6 | 16.4 | 48.9 | 59.4 | 15.6 | 37.7 | 19.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| 18:3n-6 | – | – | – | – | 21.7 | – | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | – |

| 20:2n-6 | 0.1 | – | – | – | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.2 | – | – |

| 20:4n-6 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| 22:5n-6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.4 | 0.1 | 7.4 | 1.0 |

| Total n-6 PUFA3 | 16.5 | 48.9 | 59.4 | 15.6 | 59.5 | 20.9 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 8.7 | 4.2 |

| 18:3n-3 | 8.3 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 55.5 | 0.2 | 31.9 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 18:4n-3 | – | – | – | – | 0.1 | – | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| 20:3n-3 | – | – | – | 0.1 | – | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | – | 0.1 |

| 20:5n-3 (EPA) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 18.8 | 8.4 | 0.8 | 16.5 |

| 22:5n-3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 3.4 |

| 22:6n-3 (DHA) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 12.4 | 8.7 | 44.0 | 27.1 |

| Total n-3 PUFA4 | 8.3 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 55.5 | 0.3 | 32.9 | 38.2 | 23.5 | 45.9 | 47.7 |

| Total PUFA5 | 24.8 | 54.0 | 59.7 | 71.1 | 59.8 | 53.8 | 47.3 | 27.4 | 54.6 | 51.8 |

| n-3:n-6 | 0.5 | 0.1 | <0.1 | 3.6 | <0.1 | 1.6 | 11.6 | 9.8 | 5.3 | 11.4 |

1Includes 15:0, 22:0 and 24:0.

2Includes 16:1n-9, 17:1, 20:1n-11 and 20:1n-7.

3Includes 20:3n-6 and 22:4n-6.

4Includes 20:4n-3.

5Includes 16:2, 16:3 and 16:4.

aSouth American fish oil (e.g. anchovy).

bNorthern hemisphere fish oil (e.g. herring).

cDHA-rich Schizochytrium sp. algal oil.

dEPA + DHA Schizochytrium sp. algal oil (DSM nutritional products).

Figure 1. Changes in the levels of fatty acids (% of total fatty acids), of either marine (- - -) or terrestrial origin (___), in the flesh of Scottish Atlantic salmon farmed between 2006–2015 (mean ± SD).

Stacked lettering above data points are in the order of 18:1n-9, EPA, DHA, 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3 respectively, and indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between years for the same fatty acid (n = 106, 174, 247, 81, 85, 393, 212, 523, 546 and 687 for 2006–2015 respectively).

Although production of the global fed aquaculture industry increased from 15 to 35 million tonnes over the period 2000–2012, the level of fish oil used within the same period remained static at around 800,000 metric tonnes per year7,27,28. Aquaculture currently uses around 75% of the global fish oil supply with 21% going towards direct human consumption27,28. The increasing demand from aquaculture and the nutraceutical and pharmaceutical industries, coupled with natural climatic events such as El Niño affecting both fish oil supply and prices, resulted in the salmonid industry, as the biggest user of fish oil (~60%), necessarily reducing the overall levels of marine ingredients in feeds. For instance, fish oil inclusion levels in Norwegian salmon feeds fell from 24% in 1990 to 11% in 201325. Consequently, commercial aquafeeds have increasingly incorporated blends of vegetable and fish or other oils to meet the nutritional requirements of the fish whilst also relieving pressure on marine resources, albeit with some compromise of the nutritional benefit to the human consumer.

Potential consequences for the human consumer

The benefits of consuming n-3 LC-PUFA in the diet with respect to health and well-being are well known. Increasing the intake of EPA and DHA has been associated with a wide range of health-promoting roles such as in the development and function of neural and eye tissue, particularly in infants, as well as in reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, inflammation, depression and other chronic conditions1,29,30,31,32. Farmed Atlantic salmon is often marketed for its health promoting properties, primarily its high n-3 LC-PUFA content. However, this benefit will decline as alternative ingredients, such as vegetable oils, replace fish oils in the feeds of salmon. For example, the greater use of vegetable ingredients in salmonid feeds has resulted in higher n-6 levels in farmed fish21,22,23,26, (see also Supplementary Table 1). Although n-6 fatty acids such as linoleic acid (18:2n-6) are considered essential in the diet, there is already a very high intake in the human diet such that an imbalance of n-6/n-3 may affect the uptake and function of the more beneficial n-3 LC-PUFA1,33.

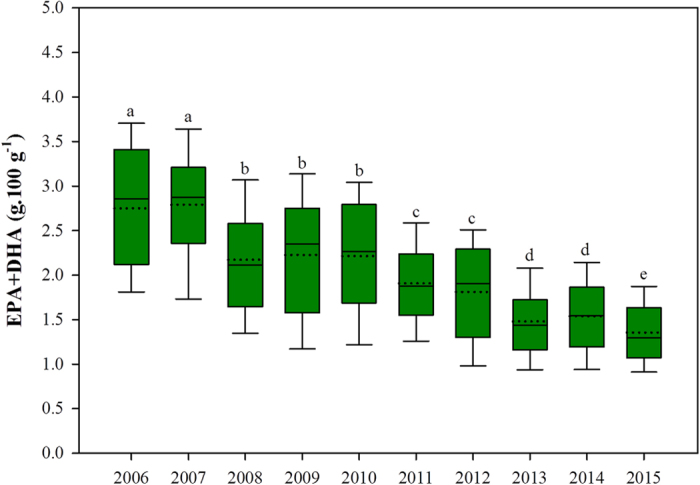

Absolute contents of EPA and DHA in the flesh of farmed Scottish Atlantic salmon have fallen significantly in recent years, decreasing on average from 2.74 g in 2006 to 1.36 g per 100 g wet weight (ww) serving in 2015 (Fig. 2). Nonetheless, this is still comparatively higher than the 1.02 g, 1.36 g and 1.00 g EPA + DHA per 100 g ww serving reported in Norwegian farmed salmon in 201134, 201225 and 201335 respectively. Although both the Scottish and Norwegian salmon farming industries are served by the same three main commercial feed producers, differences in feed formulations between countries exist. The Norwegian salmon industry for example appears to focus largely on sustainability and produces a narrow range of product specifications, all with decreased reliance on marine ingredients in favour of terrestrial alternatives25. In contrast, the Scottish salmon industry is more complex and bespoke catering for both the value and premium markets primarily driven by retailers, the former being variable in n-3 LC-PUFA content and the latter formulated to deliver a high level of n-3 LC-PUFA such that one portion provides an adequate weekly intake for humans. This has resulted in a wide range of feeds being produced with formulation data difficult to access due to retailer confidentiality. This is clearly evident from the variation and ranges of the fatty acid composition and content data presented in Figs 1 and 2.

Figure 2. Levels of EPA + DHA (g.100 g−1) in farmed Scottish Atlantic salmon between 2006 and 2015.

Median (—), mean (…), interquartile range (box) and 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers) are presented. Significant differences (P < 0.05) between mean values are indicated by different lettering (n = 106, 174, 247, 81, 85, 393, 212, 523, 546 and 687 for 2006–2015 respectively).

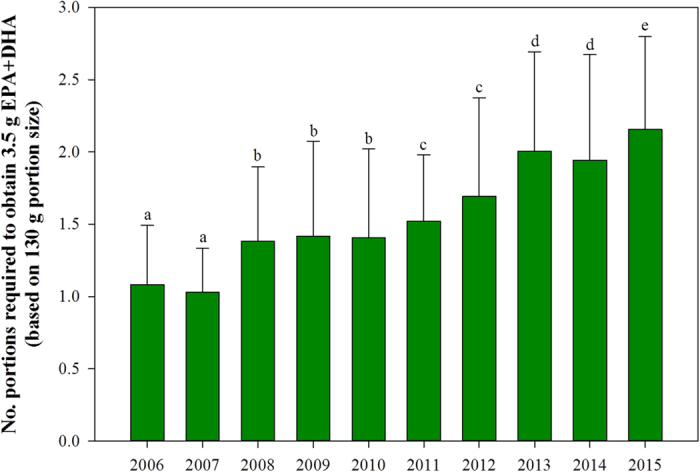

Public health bodies such as the UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) and the American Heart Association (AHA) currently advise consuming at least two portions of fish per week, of which one should be oily3,4,5,6,7,8. With EPA and DHA levels in farmed salmon decreasing, a more effective approach would be through the establishment of Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) levels. However, there is no general consensus among health and scientific organisations, with 51 National and International expert bodies all suggesting variable DRI levels according to an individual’s health status3. For example, the AHA has no recommended DRI levels for the ordinary consumer but suggests a daily intake of 1.0 g EPA + DHA for those individuals with established cardiovascular disease7,8. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) suggest that all adults should be consuming 250 mg EPA + DHA per day respectively through oily fish consumption36, whereas the International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids (ISSFAL) recommends a minimum daily intake of 500 mg to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease37. Based on a 130 g portion, as advised by EFSA38, one portion of farmed Scottish salmon in 2015 would more than satisfy the daily DRI levels mentioned above, providing 1.8 g EPA + DHA. Nevertheless, since fish and seafood are the major dietary source of EPA and DHA in the human diet and are generally limited to one to two meals per week, it may be more appropriate to express the DRI on a weekly basis. Thus, a single 130 g portion of Scottish salmon farmed in 2006 would have been adequate to meet the 3.5 g EPA + DHA weekly intake level set by ISSFAL, whereas in 2015 this would have required two portions (Fig. 3). However, it is important to highlight that while the present results relate to Scottish averages there will be salmon products which will require both larger or smaller portion sizes to meet the DRI, based on the levels of fish oil in their diets. Few retailers state the EPA and DHA content on pre-packaged salmon products at present35, possibly due to the changing levels of fish oils in diets but also due to inter-pack variation as both lipid and fatty acid content can vary according to the type of cut consumed39,40.

Figure 3. Number of portions required (mean ± SD) to obtain a weekly intake of 3.5 g EPA + DHA (ISSFAL, 2004)36, based on a 130 g serving37.

Significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by different lettering (n = 106, 174, 247, 81, 85, 393, 212, 523, 546 and 687 for 2006–2015 respectively).

Farmed versus wild

Aquaculture is often viewed in a less favourable perspective than some other farming sectors. One popular misconception among consumers is that farmed fish are inferior in terms of quality and nutritional content than wild fish. In reality, farmed fish have been found to contain as much or, in most instances, more grams of EPA + DHA per serving than their wild-caught counterparts6,35,38. Moreover, it is often quoted that farmed salmon contains more fat and is less healthy than wild salmon. Lipids (fat) supply approximately twice the amount of energy as either protein or carbohydrates. Farmed fish such as Atlantic salmon are often fed a high-energy (lipid) diet to ensure optimal growth rate while sparing the more expensive dietary protein for conversion into muscle protein20. The lipid content of Scottish Atlantic salmon farmed between 2006 and 2015 remained largely consistent (~12–13%), although some significant differences were observed between years (Supplementary Table 1). Nonetheless, these values are within the range reported elsewhere for farmed Atlantic salmon from different regions25,26, as well as for farmed salmon products found in UK supermarkets35. Wild salmon are capable of accumulating similar lipid levels to farmed salmon41. However, the lipid content of wild fish varies according to its nutritional state, which is affected by season, food availability, species, age, sex and developmental or reproductive status20,42. The lower levels (~4%) generally reported for wild salmon relate to the time when they are caught, typically during their return migration to rivers to spawn when the large lipid deposits accumulated have been mobilised and depleted to support gonadal development as well as supply the energy expended during migration itself42.

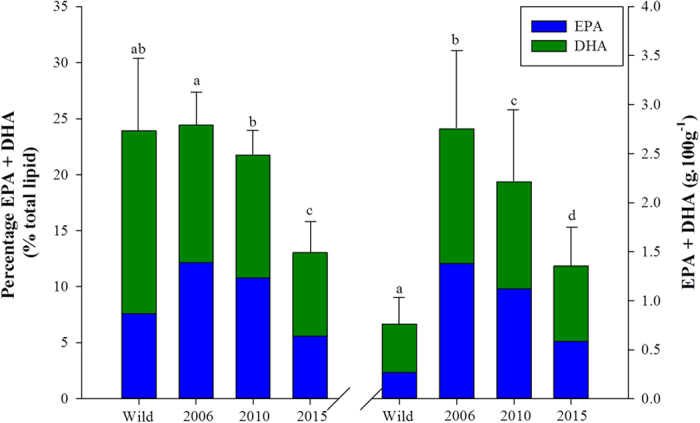

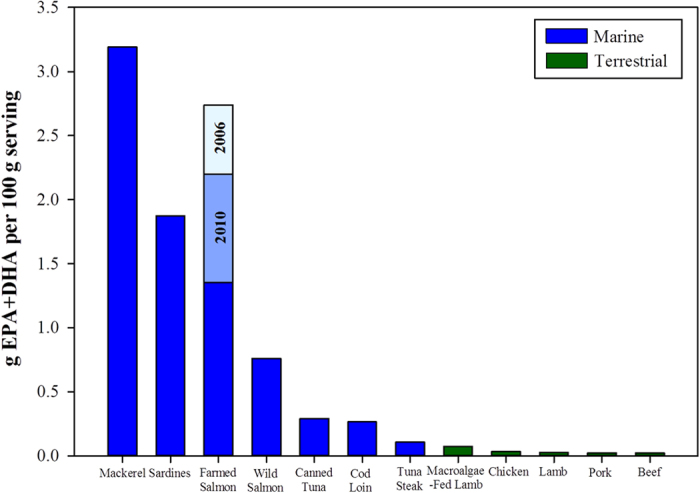

The aforementioned difference in lipid content between wild and farmed fish greatly affects the nutritional content, although the overall n-3 LC-PUFA levels in the flesh are ultimately determined by the levels in the feed. Fatty acid profiles are often presented as a percentage of the total lipid. This often leads to a further misinterpretation made by consumers regarding the perceived higher n-3 LC-PUFA nutritional content of wild fish compared to their farmed equivalents. In 2006, farmed Scottish Atlantic salmon flesh contained a similar proportion of EPA and DHA in the total lipid of their flesh to wild salmon (~24%, Fig. 4), owing to a high inclusion level of fish oil in the diet resulting in a fatty acid profile similar to that of the natural diet. Conversely, by 2010 the proportion of EPA and DHA in flesh lipid had significantly fallen to 21.7% and by 2015 to 13.0% which, at first glance, would suggest that wild salmon are more nutritionally beneficial to the human consumer. However, when expressed in absolute terms, i.e. grams of EPA + DHA per 100 g ww serving, which takes into account the lipid content of the flesh we find that, despite the reduction in EPA and DHA levels due to the increased use of plant ingredients in salmon feeds, farmed Atlantic salmon still provide a significantly higher amount of EPA + DHA than wild salmon, yielding 2.75, 2.21 and 1.36 g per 100 g ww flesh for salmon farmed in 2006, 2010 and 2015 respectively, compared to 0.76 g per 100 g ww flesh for wild salmon (Fig. 4). Furthermore, despite the decrease in the levels, farmed Scottish salmon still delivers more EPA + DHA than most other fish species as well as all farmed terrestrial livestock (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, if the continuing trend for the increased use of plant ingredients in salmon feeds endures then the risk of negating the beneficial effects from farmed salmon consumption will be realised.

Figure 4. Differences in the proportions (% of total fatty acids) and absolute levels (g.100 g−1) of EPA + DHA fatty acids between wild (Pacific species) and farmed Scottish Atlantic salmon from 2006, 2010 and 2014 (mean ± SD).

Bars bearing different lettering indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) (n = 21 for wild salmon and 106, 85 and 687 for Scottish Atlantic salmon farmed in 2006, 2010 and 2015 respectively). Stacked bars represent contribution of EPA and DHA to total values for comparative purposes.

Figure 5. Comparison between the levels of EPA + DHA (g.100 g−1) in Scottish farmed Atlantic salmon compared to other fish species (blue) and terrestrially (green) produced animals.

Stacked bars for farmed Scottish Atlantic Salmon indicate the decline in EPA + DHA levels for 2006, 2010 and 2015 respectively. All samples are based on duplicate analysis and analysed in 2014/15, with exception to wild salmon (Pacific species, n = 21) and Scottish farmed Atlantic salmon (n = 106, 85 and 687 for 2006, 2010 and 2015 respectively). Refer to methodology for further information on species sampled.

Future sources of EPA and DHA

Fish oil is still the main dietary source of EPA and DHA in the human diet. It is estimated that the annual demand for n-3 LC-PUFA to supply the global population of seven billion with 500 mg EPA + DHA per day, as recommended by ISSFAL37, is 1.25 million metric tonnes which is far greater than the estimated current total supply from all sources of just over 0.8 million metric tonnes2,43. Therefore, there is a major chronic shortfall in EPA and DHA to supply human requirements and demand. The aquaculture industry has employed several strategies to reduce fish oil use while maintaining the nutritional benefits of farmed salmon consumption. This not only includes the blending of fish and vegetable oils in commercial feeds as previously mentioned but also extends to the use of finisher feeds, whereby fish are fed a plant-based diet for the major duration of the ongrowing production cycle before switching to a fish-oil diet in the final weeks prior to harvest to increase the content of beneficial n-3 LC-PUFA21,22,23. However, this method still relies upon the inclusion of fish oil in the feeds.

In the marine environment, microalgae are the primary producers of n-3 LC-PUFA that are subsequently consumed and accumulated through the food chain to give the high levels of EPA and DHA that we generally find in marine, especially oily, fish. Therefore, microalgae represent potential feedstock for food and feed. Indeed, algal products are already used in human nutrition, particularly in the infant formula market, with 75% of the production volume used in the health food market as dietary supplements44. Accordingly, microalgae have been investigated as a promising alternative to the traditional marine derived ingredients in fish feeds, although these have largely been limited to DHA-producing species45,46. The main production of n-3 LC-PUFA by microalgae has predominantly focussed on heterotrophic species (e.g. Schizochytrium, Crypthecodinium and Ulkena species) that are cultivated by fermentation similar to yeasts under controlled conditions that give a higher production efficiency44. However, this technology is still regarded as being in the development stage resulting in low production volumes and higher costs44 which, at present, are far more expensive than for fish oil and meal45. Nevertheless, the main issues concerning the industry with respect to increasing the scale of production while simultaneously decreasing the production cost are expected to be addressed within the next few years44. Thus, in the future, microalgae will likely become available as a feed ingredient although, at present, they are unlikely to fulfil aquaculture demands for n-3 LC-PUFA. Further alternative marine sources of n-3 LC-PUFA include the use of krill47 or calanoid copepods48, although again production volumes are expected to be low and there is concern over the possible effects that harvesting down the trophic chain may have on higher trophic species that are normally reliant on these zooplankton49.

Perhaps surprisingly, future de novo n-3 LC-PUFA sources may originate from land-based supplies. Genetically modified (GM) oilseed crops have been engineered to synthesise the n-3 LC-PUFA, EPA and DHA, not normally associated with plant sources. This involves inserting specific microalgae genes that encode for the biosynthetic enzymes required to produce these specific fatty acids to generate seeds that accumulate oils with up to 20% of total fatty acids as n-3 LC-PUFA50,51. These GM crops have been demonstrated to be an effective replacement for fish oil in salmon feeds43,52. Although there is currently no commercial production, the potential for production to increase rapidly means that in the near future volumes could be considerable, although changing public perceptions and attitudes towards GM products are required, particularly in some European countries, before these GM oils can be used on a commercial scale. Nonetheless, an n-3 LC-PUFA GM yeast strain is currently being used within the Chilean salmon industry to give a niche product53 although, as with microalgae production, the fermentation technology used to produce the yeast is currently expensive and unlikely to produce sufficient volumes to meet aquaculture demand in the near-future. However, both the microalgae and GM technologies offer clear potential to counter the global deficit of n-3 LC-PUFA sources and reverse the trend of decreasing levels of EPA and DHA in farmed fish and thus ensure that farmed Atlantic salmon will continue to maintain its nutritional benefit to the human consumer in the future.

Materials and Methods

Sample data

The present study examined over 3,000 fatty acid profiles of farmed Scottish salmon analysed between 2006 and 2015 by the Nutrition Analytical Service (NAS), Institute of Aquaculture, University of Stirling. Samples were provided year-round by a wide range of salmon producers and feed manufacturers, reflecting the continual production of the Scottish salmon industry. All samples included in the study were deemed to be representative of the commercial Scottish salmon industry, with trial fish, fish purchased from supermarkets or whose farmed location was otherwise unknown excluded from the study. The samples were processed by NAS in a laboratory working towards ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation. Briefly, samples of standard quality cuts, a standardised muscle section used in flesh quality determination corresponding to the region of flesh between dorsal fin and anal fin, were shipped to NAS on ice and processed that day. All samples were skinned and boned before being thoroughly homogenised prior to analysis.

To compare the EPA and DHA levels (g.100 g−1 ww) in farmed Scottish salmon with other marine and terrestrial food products, samples of fresh Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) fillets, Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) loin, tuna steak (Yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares), beef, chicken breast, lamb, macroalgae-fed lamb (North Ronaldsay, Orkney, Scotland) and pork meat, together with canned tuna in spring water (Skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis) and tinned sardines in spring water (Sardina pilchardus) were purchased from local retailers during late 2014/early 2015 and analysed as previously described. Wild salmon samples (n = 21), generally Pacific salmon species (Oncorhynchus kisutch, O. nerka or O. keta), were purchased from supermarkets between 2006 and 2015 and analysed as described for farmed salmon. No differences in EPA + DHA content (g.100 g−1 ww) were observed between years, thus wild salmon samples were pooled.

Lipid and fatty acid determination

Total lipid was extracted from ~0.5 g of homogenised salmon flesh in 20 volumes of ice-cold chloroform/methanol (2:1 v/v) using an Ultra-Turrax tissue disruptor (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) and the lipid determined gravimetrically54. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) from total lipid were prepared by acid-catalysed transmethylation at 50 °C for 16 h55. FAME were extracted and purified as described previously56, and separated and quantified by gas-liquid chromatography using a Fisons GC-8160 (Thermo Scientific, Milan, Italy) equipped with a 30 m × 0.32 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm ZB-wax column (Phenomenex, Cheshire, UK), ‘on column’ injection and flame ionisation detection. Hydrogen was used as carrier gas with an initial oven thermal gradient from 50 °C to 150 °C at 40 °C.min−1 to a final temperature of 230 °C at 2 °C.min−1. Individual FAME were identified by comparison to known standards (Supelco™ 37-FAME mix; Sigma-Aldrich Ltd., Poole, UK) and published data56. Data were collected and processed using Chromcard for Windows (Version 1.19; Thermoquest Italia S.p.A., Milan, Italy). Fatty acid content per g of tissue was calculated using heptadecanoic acid (17:0) as internal standard.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab® v.17.1.0 statistical software (Minitab Inc., PA, USA). Data were assessed for normality with Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and for homogeneity of variances by Bartlett’s test and examination of residual plots and, where necessary, transformed using arcsine or natural logarithm transformation. Data were compared by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with replicate post hoc comparisons made using Tukey’s test57. A significance of P < 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests performed. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Sprague, M. et al. Impact of sustainable feeds on omega-3 long-chain fatty acid levels in farmed Atlantic salmon, 2006-2015. Sci. Rep. 6, 21892; doi: 10.1038/srep21892 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of NAS staff, past and present, in the analytical procedures.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.S. collated and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions from J.R.D. and D.R.T.

References

- Calder P. C. Very long chain omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids and human health. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech. 116, 1280–1300 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Tocher D. R. Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and aquaculture in perspective. Aquaculture, 449, 94–907 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Global Organisation for EPA and DHA (GOED), Global recommendations for EPA and DHA intake. (Rev. 19 November 2014) Available at: http://issfal.org/GlobalRecommendationsSummary19Nov2014Landscape_-3-.pdf. (Accessed: March 2015).

- Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. WHO technical report series 916. pp. 149. (World Health Organisation (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland, 2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition and Committee on Toxicity (SACN/COT). Advice on fish consumption: benefits and risks. 204 pp. (The Stationary Office, Norwich, UK, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services (USDA), Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2015). Available at: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/pdfs/scientific-report-of-the-2015-dietary-guidelines-advisory-committee.pdf (Accessed: August 2015).

- American Heart Association (AHA), Fish 101. (2015) Available at: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/Fish-101_UCM_305986_Article.jsp#aha_recommendation (Accessed: August 2015).

- Kris-Etherton P. M., Harris W. S. & Appel L. J. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 106, 2747–2757 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). The State of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2012. (FAO, Rome, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kontali Analyse. Salmon World 2013, 32 pp. (Kontali Analyse AS, Norway (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Salmon Producers Organisation (SSPO), Scottish salmon industry: Growing a sustainable industry 2014. (2014) Available at: http://scottishsalmon.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Sustainability-Booklet-2014_1806.pdf (Accessed: June 2015).

- The Commission of European Communities. Commission Regulation (EC) No 1437/2004 of 11 August 2004 supplementing the Annex to Regulation (EC) No 2400/96 on the entry of certain names in the ‘Register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications’ (‘Valençay’, ‘Scottish Farmed Salmon’, ‘Ternera de Extremadura’ and ‘Aceite de Mallorca’ or ‘Aceite mallorquín’ or ‘Oli de Mallorca’ or ‘Oli mallorquí’). OJ. L. 265, 12.8.2004, 3–4 (2004).

- Food and Drink Federation (FDF), UK food and drink export statistics for 2014. (2015) Available at: http://www.fdf.org.uk/exports/ukexports.aspx (Accessed: July 2015).

- Naylor R. L. et al. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature, 405, 1017–1024 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor R. L. et al. Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15103–15110 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J. R. & Tacon A. G. Development of farmed fish: a nutritionally necessary alternative to meat. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 58, 377–383 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacon A. G. J. & Metian M. Fish matters: importance of aquatic foods in human nutrition and global food supply. Rev. Fish. Sci. 21, 22–38 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Tacon A. G. J. & Metian M. Global overview on the use of fish meal and fish oil in industrially compounded aquafeeds: Trends and future prospects. Aquaculture, 285, 146–158 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Torrissen O. et al. Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): The “Super-Chicken” of the sea? Rev. Fish. Sci. 19, 257–278 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J. R., Tocher D. R. & Bell J. G. The Lipids in Fish Nutrition 3rd edn, (eds Halver J. E. & Hardy R. W.) Ch. 4, 181–257 (Elsevier Science, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. G., Henderson R. J., Tocher D. R. & Sargent J. R. Replacement of dietary fish oil with increasing levels of linseed oil: Modification of flesh fatty acid compositions in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) using a fish oil finishing diet. Lipids, 39, 223–232 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. G., Tocher D. R., Henderson R. J., Dick J. R. & Crampton V. O. Altered fatty acid compositions in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fed diets containing linseed and rapeseed oils can be partially restored by a subsequent fish oil finishing diet. J. Nutr. 133, 2793–2801 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torstensen B. E. et al. Tailoring of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) flesh lipid composition and sensory quality by replacing fish oil with a vegetable oil blend. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 10166–10178 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nøstbakken O. J. et al. Contaminant levels in Norwegian farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in the 13-year period from 1999 to 2011. Environ. Int. 74, 274–280 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ytrestøyl T., Aas T. S. & Åsgård T. Utilisation of feed resources in production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture, 448, 365–374 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Nichols P. D., Glencross B., Petrie J. R. & Singh S. P. Readily available sources of long-chain omega-3 oils: Is farmed Australian seafood a better source of the good oil than wild-caught seafood? Nutrients, 6, 1063–1079 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd C. J. & Jackson A. J. Global fishmeal and fish-oil supply: inputs, outputs and markets. J. Fish Biol. 83, 1046–1066 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd C. J. & Bachis E. Changing supply and demand for fish oil. Aquaculture Econ. Manage 18, 395–416 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Calder P. C. & Yaqoob P. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and human health outcomes. Biofactors, 35, 266–272 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoy C., Escolano-Margarit M. V., Anjos T., Szajewska H. & Uauy R. Omega 3 fatty acids on child growth, visual acuity and neurodevelopment. Br. J. Nutr. 107, S85–S106 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer S. K., Psota T. L., Harris W. S. & Kris-Etherton P. M. n-3 fatty acid dietary recommendations and food sources to achieve essentiality and cardiovascular benefits. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83, S1526–S1535 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles E. A. & Calder P. C. Influence of marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on immune function and a systematic review of their effects on clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Nutr. 107, S171–S184 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos A. P. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp. Biol. Med. 233, 674–688 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen I. J. et al. Farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) is a good source of long chain omega-3 fatty acids. Nutr. Bull. 37, 25–29 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Henriques J., Dick J. R., Tocher D. R. & Bell J. G. Nutritional quality of salmon products available from major retailers in the UK: content and composition of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Br. J. Nutr. 112, 964–975 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, European Food Safety Authority. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol. EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition and allergies (NDA). EFSA J. 8, 1461 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids (ISSFAL). Report of the sub-committee on: Recommendations for intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids in healthy adults. (ISSFAL, Brighton, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, European Food Safety Authority Opinion of the scientific panel on contaminants in the food chain on a request from the European Parliament related to the safety assessment of wild and farmed fish. EFSA J. 236, 1–118 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. G. et al. Flesh lipid and carotenoid composition of Scottish farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). J. Agr. Food Chem. 46, 119–127 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katikou P., Hughes S. I. & Robb D. Lipid distribution within Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fillets. Aquaculture, 202, 89–99 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. C. et al. Lipid composition and contaminants in farmed and wild salmon. Enivron. Sci. Tech. 39, 8622–8629 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J. G. Current aspects of lipid nutrition in fish farming. In Biology of Farmed Fish (eds Black K. D. & Pickering A. D.) 114–145 (Sheffield Academic Press Ltd. 1998). [Google Scholar]

- Betancor M. B. et al. A nutritionally-enhanced oil from transgenic Camelina sativa effectively replaces fish oil as a source of eicosapentaenoic acid for fish. Sci. Rep. 5, 8104 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani M. et al. Food and feed products from microalgae: market opportunities and challenges for the EU. Trends Food. Sci. Tech. 42, 81–92 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Sprague M. et al. Replacement of a fish oil with a DHA-rich algal meal derived from Schizochytrium sp. on the fatty acid and persistent organic pollutant levels in diets and flesh of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar, L.) post-smolts. Food Chem. 185, 413–421 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C. G., Bransden M. P., Lewis T. E. & Nichols P. D. Potential of Thraustochytrids to partially replace fish oil in Atlantic salmon feeds. Mar. Biotech. 5, 480–492 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R. E. et al. The replacement of fish meal with Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba in diets for Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Aq. Nutr. 12, 280–290 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R. E. et al. Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, utilizes wax ester-rich oil from Calanus finmarchicus effectively. Aquaculture, 240, 433–449 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Hill S. L., Murphy E. J., Reid K., Trathan P. N. & Constable A. J. Modelling Southern Ocean ecosystems: krill, the food-web, and the impacts of harvesting. Biol. Rev. 81, 581–608 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Lopez N., Haslam R. P., Napier J. A. & Sayanova O. Successful high level accumulation of fish oil omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in a transgenic oilseed crop. Plant J. 77, 198–208 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher S., Haslam R. P., Ruiz-Lopez N., Sayanova O. & Napier J. A. Field trial evaluation of the accumulation of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in transgenic Camelina sativa: Making fish oil substitutes in plants. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2, 93–98 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancor M. B. et al. Evaluation of a high-EPA oil from transgenic Camelina sativa in feeds for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.): Effects on tissue fatty acid composition, histology and gene expression. Aquaculture, 444, 1–12 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlasso®, Fish in, fish out: conserving wild fish populations. (2015) Available at: http://www.verlasso.com/farming/fish-in-fish-out/about-our-yeast/(Accessed: July 2015).

- Folch J., Lees M. & Sloane Stanley G. H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie W. W. Preparation of derivatives of fatty acids for chromatographic analysis. In Advances in Lipid Methodology Two (ed. Christie W. W.), pp. 69–111 (The Oily Press, 1993). [Google Scholar]

- Tocher D. R. & Harvie D. G. Fatty acid compositions of the major phosphoglycerides from fish neural tissues: (n-3) and (n-6) polyunsaturated fatty acids in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri L.) and cod (Gadus morhua) brains and retinas. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 5, 229–239 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zar J. H. Biostatistical Analysis, 663 pp. (Prentice-Hall International, 1999). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.