Abstract

Previous studies on school-based mindfulness and yoga programs have focused primarily on quantitative measurement of program outcomes. This study used qualitative data to investigate program content and skills that students remembered and applied in their daily lives. Data were gathered following a 16-week mindfulness and yoga intervention delivered at three urban schools by a community non-profit organization. We conducted focus groups and interviews with nine classroom teachers who did not participate in the program and held six focus groups with 22 fifth and sixth grade program participants. This study addresses two primary research questions: (1) What skills did students learn, retain, and utilize outside the program? and (2) What changes did classroom teachers expect and observe among program recipients? Four major themes related to skill learning and application emerged as follows: (1) youths retained and utilized program skills involving breath work and poses; (2) knowledge about health benefits of these techniques promoted self-utilization and sharing of skills; (3) youths developed keener emotional appraisal that, coupled with new and improved emotional regulation skills, helped de-escalate negative emotions, promote calm, and reduce stress; and (4) youths and teachers reported realistic and optimistic expectations for future impact of acquired program skills. We discuss implications of these findings for guiding future research and practice.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Yoga, Skills, School-based, Youth, Qualitative

Introduction

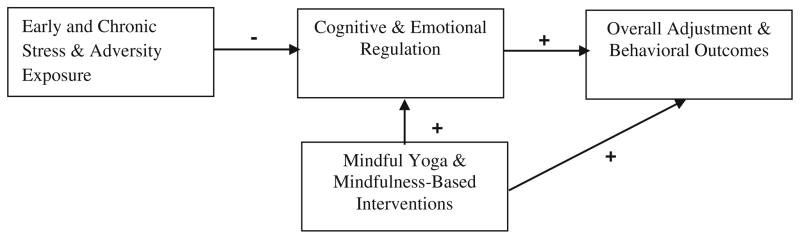

Mindfulness- and yoga-based programs targeting primary and secondary school-aged youths are increasingly being implemented given their purported benefits for stress reduction; emotional regulation; improved mental and physical health; and enhanced social-emotional, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes (Greenberg and Harris 2011; Weare 2013; Zoogman et al. 2014). The mindful yoga program assessed in this study is predicated on the theory that increased present-moment awareness (e.g., awareness of feeling stressed) coupled with learned regulation skills (e.g., breathing, physical poses) will promote positive reactions to stress and decrease negative coping strategies (e.g., substance use). Mindfulness and yoga programs are hypothesized to have potential benefits for youth living in impoverished environments by mitigating the harmful effects of chronic stress exposure through promotion of self-regulatory capacities (Brown and Ryan 2003; Mendelson et al. 2010; Zenner et al. 2014). Youths in disadvantaged communities often experience early and chronic life stressors (Grant et al. 2004). Toxic stress exposure affects brain development and stress responses, negatively influencing cognitive functioning and emotional regulation capabilities and, in turn, increasing the risk for negative emotional and behavioral outcomes (Teicher et al. 2002).

Research on stress exposure informed the conceptual model shown in Fig. 1. This model suggests that mindful yoga may improve youth behavioral outcomes by positively influencing youths’ emotional and cognitive regulation (Mendelson et al. 2010; Feagans Gould et al. 2014). A hypothesis related to this model is that mindfulness and yoga interventions may improve self-regulation through the practice of present-moment awareness and calming the body using breath work, yogic body postures, and guided attention training. A direct relationship between mindful yoga and outcomes is included to account for other intervention mechanisms of action that may not be mediated by changes in self-regulation (e.g., youth empowerment).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of mindful yoga. Adapted from Mendelson et al. 2010; Feagans Gould et al. 2014

While research has begun to evaluate the effects of school-based mindfulness and yoga programs on quantitative youth outcomes (Diamond and Lee 2011; Khalsa et al. 2012; Lagor et al. 2013; Noggle et al. 2012; Serwacki and Cook-Cottone 2012; Zenner et al. 2014), few investigators have explored the perspectives of students and teachers using qualitative data. Qualitative data can provide substantive information about student learning and application of skills, which has potential to deepen our understanding of intervention mechanisms of action. This information can guide future research and practice with respect to measuring proximal and distal outcomes and intervention components.

Qualitative studies focusing on outcomes of school-based mindfulness and yoga programs have described youth-reported program benefits with respect to school-level factors (e.g., school climate; classroom engagement) and individual-level behavioral (e.g., breathing; constructive self-distraction; improved sleep); cognitive (e.g., awareness, attentiveness, forward thinking); emotional (e.g., calm, relaxation); and social outcomes (e.g., self-assertion, improved peer relationships) (Case-Smith et al. 2010; Conboy et al. 2013; Metz et al. 2013; Tharaldsen 2012; Wisner 2013). A limited number of qualitative studies have focused on understanding process components, such as students’ experience of learning skills, in contrast to program outcomes. A study on 40 high school youths participating in the Conscious Coping Program (Tharaldsen 2012) found that qualitative data helped in understanding youth perceptions of the program and program expectations and what they remembered from the exercises, although they could not articulate specific skills taught. A study of 11 participants (ages 16–24) used qualitative data to describe three phases (distress and reactivity, stability, and insight and application) through which participants progressed as they became more mindful during a 6-week mindfulness program (Monshat et al. 2013). Most qualitative studies have focused on high school-aged students; however, with far fewer including elementary- or middle school-aged youths.

The few qualitative studies assessing mindfulness- or yoga-based programs among elementary and middle school youths have typically used single informants, with the exception of Campion and Rocco (2009), who qualitatively evaluated a classroom-based meditation program in three Australian Catholic schools using a subset of elementary school students, their parents, and teachers. Data from single informants provides only one perspective whereas multiple informant data (some combination of students, classroom teachers, implementers, parents) can be triangulated to provide a more comprehensive understanding of program processes and effects. A notable limitation of many of these qualitative studies is the primary reliance on quantitative assessments with limited open-ended survey items and/or semi-structured interview questions about students’ satisfaction with the program, frequency (not content) of homework completion, implementation-related topics (e.g., attendance, feasibility), and perceived usefulness of the program (Broderick and Metz 2009; Conboy et al. 2013; Metz et al. 2013; Tharaldsen 2012). These types of qualitative data are generally somewhat limited with respect to implications for understanding intervention processes and skills learned or applied.

The current study used both student and teacher informants and open-ended questions to provide a participant-grounded understanding of the mindfulness skills students learned and applied. Participants were fifth and sixth grade youths who voluntarily participated in a 16-week mindfulness and yoga school-based intervention implemented by an external nonprofit organization, as well as their classroom teachers who did not participate in the program. This study contributes to the literature by exploring process-related components (e.g., skills learned), by representing the perspectives of understudied middle school students from disadvantaged communities where exposure to toxic stress is common, and by including both student and teacher perspectives. Our evaluation of process components—which skills youths remembered and described as important to them—is important for informing recommendations for future evaluation measures and designs. We investigated two research questions using focus group data from student participants and interview and focus group data from their classroom teachers: (1) What do youths learn, retain, and utilize outside the program? and (2) What changes do classroom teachers expect and observe among program recipients?

Method

Participants

Qualitative data were collected from 22 fifth and sixth grade students (age range=10 to 13; mean age=11.3; median age= 11; students reported whole ages) as well as nine of their classroom teachers across three intervention schools (denoted as schools 1, 2, and 3; see Table 1 for school and neighborhood characteristics) to assess what school-aged program recipients learned from the program and what they reported practicing in their regular classrooms and outside of school. Focus groups and interviews with students and teachers were conducted in the three intervention schools after programming ended.

Table 1.

School and area characteristics

| Failure to Reach Proficiency on MSAa,b

|

Race/ethnicitya

|

Economic indicators

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading

|

Math

|

Black | White | Hispanic | Median HH income in zip code (2011 US$)c | Unemploymentc,d | |||

| 5th | 6th | 5th | 6th | ||||||

| School | |||||||||

| 1 | 35.0 | 61.0 | 53.0 | 57.0 | 97.0 | 1.0 | <1 | 35,620 | 15.5 |

| 2 | 22.0 | 16.0 | 53.0 | 30.0 | 88.0 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 47,472 | 11.4 |

| 3 | 21.0 | 55.0 | 21.0 | 68.0 | 96.0 | <1 | 2.0 | 31,018 | 16.5 |

| State mean | 9.8 | 16.2 | 17.7 | 19.0 | 70,004 | 7.4 | |||

Baltimorecityschools.org

Mdreportcard.org

City-data.com

The three intervention schools served highly disadvantaged urban communities with rates of poverty and crime that are among the worst in the nation, as shown in Table 1. Median household income was half the state average for the communities served by two of the three schools, and unemployment was over twice the state average in these areas (Table 1). Test scores at the three schools also highlight significant disparities with state-level academic achievement. State averages for failing to reach proficiency on the Maryland School Assessment (MSA) exam for fifth and sixth graders for reading were 9.8 and 16.2 %, respectively and for math were 17.7 and 19 % (Sadusky 2011). For the three intervention schools, failure to reach proficiency in reading ranged from 16 to 61 % and in math ranged from 21 to 68 % (Table 1).

After program completion, classroom teachers were asked to identify youths who varied in terms of grade, sex, program attendance, and program engagement to participate in focus group discussions. Although they did not participate in the program, classroom teachers were aware of students’ attendance and engagement in the program, informed by brief conversations with the program implementers. A total of 14 fifth graders and 8 sixth graders participated in focus groups. With respect to classroom teacher data, in two of the three schools, all fifth and sixth grade primary classroom teachers of the students who participated in the program were interviewed. In one school (school 1), only sixth grade teachers were available for interviewing due to scheduling conflicts. Youth and teacher characteristics by school, grade, race, and biological sex are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Focus group sample characteristics and intervention program characteristics

| Sample characteristics | Schools

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1

|

2

|

3

|

||||

| Student | Teacher | Student | Teacher | Student | Teacher | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Male | 2 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Grade | ||||||

| 5th | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 6th | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 6 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| White/Other | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 8 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 2 |

| Program Characteristics (entire sample of youth) | N=43 | N=54 | N=33 | |||

| Dosage | ||||||

| Sessions (32 max) | 25 | 24 | 32 | |||

| Attendance (# sessions attended) | 14.4 | 9.2 | 27.5 | |||

| Timing | Resource time | Lunch time | Resource time | |||

Procedure

School-Based Mindful Yoga Program Description

Data for this study were drawn from a larger quasi-randomized control trial. Six schools were paired by student test scores and sociodemographic characteristics, and one school per pair was assigned to receive the intervention (n=130 students), whereas the three other schools received standard school programming (n=122 students). School assignment was not completely random; one school was assigned to the intervention condition due to other concurrent intervention programming at the school. The current study focused on qualitative data gathered from a subset of participants at the three intervention schools after intervention completion. A school-based mindful yoga program was implemented by three yoga instructors who founded the Holistic Life Foundation (HLF), a Baltimore-based non-profit organization. Each yoga instructor—the three HLF founders—worked with an assistant instructor they had trained. Each pair (founder and assistant) worked with one of the three intervention schools. Students self-selected into the program by providing assent and obtaining parental permission prior to enrollment. In one school with fewer students (school 3), almost all students participated in the program. Classroom teachers did not participate in the program.

The program was delivered twice per week for 16 weeks. Sessions lasted approximately 45 min each and were taught during resource time (e.g., art, library, music) in schools 1 and 3 and during part of the lunch period in school 2. Program classes each contained approximately 25 students. Fifth and sixth grade students were taught separately in schools 1 and 3 and together in school 2. The curriculum teaches mindfulness principles and practices, including yoga-based poses and breathing techniques focused on present-moment awareness, in a secular and developmentally appropriate manner. A typical session started with centering practices (quiet breathing), followed by active yoga-based poses and breathing techniques, and ended with a guided reflection involving focused attention (e.g., sending kindness to others). These practices began at a basic level and increased in complexity over time. Sessions included brief discussion topics such as defining stress, identifying stressors, and using mindfulness techniques to manage stress and promote health. Youths were given assignments between sessions to reinforce lessons; some focused on physical aspects (e.g., chair pose) while others promoted cognitive (e.g., increased awareness) and emotional (e.g., empathy) aspects. (For more detail on program components, see Feagans Gould et al. 2014).

Focus Groups

Six youth focus groups—two at each of the three intervention schools—were conducted after the program was completed. Youth focus groups averaged 35 min and ranged from 2–6 students. For five of the six youth focus groups, fifth and sixth grade youths were interviewed separately. Two interviews and two focus groups (one with five teachers and another with two teachers) lasting approximately 30 min were conducted with teachers either during resource time or lunch.

Measures

Focus group discussion guides were created for youths and teachers. Topics covered during the youth focus groups that specifically relate to this paper included what students learned during the program (e.g., “Tell me what is most important that you have learned in the program”) and outside application of skills and lessons learned in the program (e.g., “Has what you learned in the program helped you outside the program? How so?,” “Have you shared what you learned in the program with others?,” “Were you able to use some of those skills outside the program?”). Youths were also encouraged to discuss their expectations for how they might use program skills in the future (e.g., “Will what you learned in the program help you in the future?”).

Teachers were asked about multiple topics including their expectations for student behavioral change as a result of the program (e.g., “When you first learned about the program, did you have any expectations of how it would influence your students?”), expectations about future program impact on students (e.g., “Do you think that positive changes are likely through this program from here forward?”), and observations of behavioral change among program participants in the classroom (e.g., “How did student participation in the program affect students’ ability to participate in their academic classes?”). Additional focus group topics are addressed in separate papers (Dariotis et al., A qualitative exploration of implementation factors in a school-based mindfulness and yoga program: lessons learned from students and teachers, accepted manuscript; Dariotis et al., Urban 5th and 6th grade students’ and teachers’ perspectives on stress and implications for mindfulness interventions, under review).

Qualitative Analysis

Focus groups and interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and verified by another research team member. Each of the ten transcripts was independently coded by the first three authors. Inductive coding occurred in three steps. First, the three coders independently reviewed and coded all ten transcripts using thematic analysis (Boyatzis 1998). The themes were data-driven and resulted from an iterative inductive process whereby qualitative data were read and coded without interpretation. Organization of codes into emergent themes resulted from re-reading and re-coding. Codes were initially recorded either by hand, in Excel, or in Word. Second, the three coders met weekly for 1 to 2 h to discuss, compare, and contrast major and sub themes that emerged via independent coding. Any coding disagreements were resolved in these meetings, resulting in consensus on emergent themes. Third, the coders classified, categorized, and organized participants’ responses by theme. This iterative process minimized the likelihood of missed or misclassified codes. Our analyses addressed themes that emerged consistently throughout the data related to learning and application of program skills.

Results

Four major themes emerged from the data: (1) Youths most readily and frequently recalled breath work and poses. (2) Youths drew linkages between technique benefits and ailments experienced by self and others, discerning which poses and skills to share with others or to personally use in times of need. (3) Youths reported keener emotional appraisal of self and others that helped reduce their impulsive and negative reactions and promote positive social interactions. New and improved emotional regulation skills applied in the classroom and outside of school, coupled with keener appraisal, helped youths de-escalate negative emotions, promote calm, and reduce stress. (4) Overall, both youths and teachers reported realistic—sometimes optimistic—expectations for the learned program skills to positively impact youths’ stress levels and behaviors during the program and in the future. We describe each theme in the following sections, drawing upon both student and teacher accounts where applicable, and discussing mixed reports, if relevant. The first three themes pertain to what youths learned, retained, and utilized outside the program (research question 1). The fourth theme pertains to youths’ expectations for future impact of the program as well as changes classroom teachers expected and observed among program recipients and how these changes affected classroom dynamics (research question 2). Program components (e.g., poses, breathing techniques) were mentioned in the context of multiple themes.

Recalling Breath Work and Poses and Their Health Benefits

When asked how they would describe the program to someone not taking the program, students most often mentioned physical components of the program, such as breathing techniques (e.g., breath of fire) and poses (e.g., sun salutation sequence), and to a lesser extent, hand gestures. Youths often used great detail to explain the breath work and poses, two of the core HLF program components (see Feagans Gould et al. 2014 for additional description of program components). Excitement about what they learned was evident as youths actively demonstrated these practices while describing them in the focus groups.

Breath Work

Nearly all students spoke at length about breathing techniques they learned and the benefits of each. They referred to the breathing techniques by name—”easy breathing,” “the tongue breathing,” “deep breathing,” “Breath of Fire,” “Ocean Breath,” and “the Cooling Breath.” Youths described and demonstrated these breathing techniques during the focus groups. Additionally, several students recalled the physiological importance of certain types of breathing (e.g., deep vs. shallow; nostril vs. mouth). The following quote illustrates how students remembered the mechanisms underlying nasal breathing:

Deep like, to inhale like a deep breath and then breathe back out your nose because when you inhale through your nose your nose hair blocks the filthy air particles and you should breathe back out your nose so you can blow them back and when you take deep breaths instead of little breaths, but you take a deep breath you get, you filter out your blood and are cleaning out your blood so you can have a better heart rate. (sixth grade female, school 3)

The level of biological detail in this quote suggests lessons learned in the yoga program may have implications for augmenting or reinforcing classroom lessons about anatomy, physiology, and biological processes, as discussed below.

Poses

Students remembered learning new poses approximately every 2 weeks (e.g., sun salutations, fountain of youth, five rites, table, chair, downward facing dog, forward and backward bends) and recounted them in detail. Even if they could not provide the name of the pose, all students described the structure and benefits of poses, with some students demonstrating the poses while describing them. Students remarked that poses served multiple purposes: (1) a form of exercise that helps keep them fit, toned, and in good shape, [“The physical activity helps and is helping all the muscles in your body and you don’t strain nothing so it’s just building you up” (sixth grade male, school 3)] as well as (2) a means of calming down and reducing stress [“I think that the person who is not in it [the program] is missing a lot because if they’re stressed or having problems, they can calm themselves down …” (fifth grade female, school 1)]. One fifth grade male noted that the program “relaxes your muscles, teaches you breathing lessons if you have trouble” (school 2).

Health Benefits of Program Practices as a Motivation for Sharing or Personal Use

Youths articulated specific physical, mental, and emotional benefits of the techniques, poses, and skills covered during the program. With the exception of two youths, these benefits motivated youths to share practices with other non-program youths (e.g., classmates, siblings, cousins) and adults (e.g., parents, aunts, family friends) afflicted with ailments certain yoga techniques could help alleviate. Many youths discerned which poses and skills to share with others or personally use based on their benefits for physical, mental, or emotional needs. Students typically used or taught skills outside the program because (1) someone they knew—mostly family members (including parents, grandparents, great aunts, siblings, cousins), teachers, or peers—solicited information about what youths were learning in the program, and/or (2) the youths identified that a lesson taught in the program would be of benefit. Program skills shared with others centered mostly on physical poses (e.g., backward and forward bends, scorpion, downward dog) and breathing techniques (e.g., breath of fire, ocean breath). As part of homework assignments, instructors encouraged students to teach practices and related benefits learned in the program to others.

Sharing via Solicitation by Others

Questions about the program from parents, teachers, and peers helped to reinforce lessons and demonstrated that youths learned the technique mechanics, as well as the health benefits of these techniques. One student described how his mother asked him about the program, leading him to demonstrate breathing techniques and poses he learned: “My mother asks me how was it, is it fun, uh, what have you been learning, can you show me some stuff that you’ve learnt … I showed her the sunrise, the Breath of Fire, Kaki, …” (fifth grade male, school 2). Another student echoed this, stating his father questioned the students’ ability to do the poses and then asked to be taught a pose: “my parents asked me ‘what do you do, and do what and if you do it right or not.’ I said ‘I do a lot of things.’ And my dad say ‘can you teach me one of the pose?’ I taught him the Sunrise” (fifth grade male, school 2). During the program, youths learned that the sunrise salutation awakens the body and mind and builds energy. Several students shared this with siblings who struggled to wake up in the mornings, as exemplified by this sixth grade female: “I shared the Sunrise ‘cuz my brother always like feels like he doesn’t want to get up in the morning so I shared that with him” (school 1).

Youths were also asked questions about how techniques helped them. For instance, one female spoke about how her parents asked how what she did in the program helped with emotional regulation: “What did I do today and like, um, like if I was mad today how did it calm me down? Like doing yoga and exercises” (fifth grade female, school 1). Another student was asked about practicing poses when in a bad mood: “Yeah, they … they just ask me like how you do moves when you are like in a bad mood” (sixth grade female, school 1). Even students who did not think the program was fun learned helpful techniques: “My, my friends they ask like is it fun and I tell them ‘No. It kinda helps like breathing and different stuff that you don’t need every day’” (fifth grade female, school 2).

Identifying Benefits of Techniques for Ailments

Several youths used the poses and breathing techniques they learned in the program to help friends and family members relieve health problems, including breathing difficulties and back pain. Asthma was a common condition affecting many of the students’ family members. In the program, youths learned that breathing techniques may help with asthma, and several youth shared the techniques with others suffering from asthma. A fifth grade female shared breathing techniques to help her asthmatic 10 year-old brother with his breathing. Another fifth grade female remarked that perhaps yoga could help her relative who became increasingly frustrated and angry with her asthmatic condition, making it worse: “We have asthma and they get mad very easily … And she’s always complaining about it. So she should do it [yoga] ‘cause it will really help her with that” (school 2). Yet another fifth grade female described how a specific type of breath work helps with asthma: “Deep Breath of Fire, I’m sayin’ ‘cause if you have asthma and you breathe in and you slowly breathe out and you, it can like help you like if you cough and stuff” (school 1).

Back pain was another common condition youth recalled yoga poses could help mitigate. One fifth grade female said that her mother—who experiences back problems and headaches—asked about which poses could help with her ailments, and this young female showed her different poses. A sixth grade male practiced a sequence of poses with his brother every day for a few weeks to help with back pain: “My brother [age 20], he hurt his back so I told him to do Sunrises. Then like after a couple weeks, he stopped hurting. Yeah I did it every morning [with him]” (school 3).

Youth recommended yoga techniques to others to help them with weight loss; general strength and flexibility; and mitigation of sore throats, arthritis, and stress. A sixth grade female shared that her mother wanted to lose weight, so she showed her mother the third rite (which is a leg lift movement) to help tone her abdominals. Youth also reported that yoga helps people later in life become stronger and more flexible and that people who practice yoga heal faster. For example, one fifth grade male taught his sister a technique he learned in the program to help relieve a sore throat when she was sick. A sixth grade male shared a hand technique he learned in the program with his mom to help her calm down, which she found helpful: “Like awhile ago when she was like really stressful like she went through something … I told her about the little, um thing …with the little finger. And she said it was really useful” (school 2). Another sixth grade male reported sharing a specific exercise with his grandmother who suffers from arthritis: “It was a move that helps cure arthritis … and I shared it with my grandmother” (school 1).

Self-Practice of Poses and Breathing Techniques

Several youths reported practicing skills and techniques outside the program to calm down, reduce anger, wake up, deal with boredom, remedy distraction, prevent impulsivity, and help with aches and pains. Most of the lessons youth practiced outside the program centered on physical poses and breath work. Self-practice was typically motivated by an ailment that could be relieved by a pose or breathing technique.

Deep breathing was the most frequently mentioned technique used outside the classroom. Initially, several students said they did not use techniques outside the program, but when they thought about it, several gave examples of using breathing techniques (e.g., in gym class to calm down when missing plays in kickball). One fifth grade female (school 3) remarked that prior to the program, she would run out of breath when running around, but that now she is less likely to be out of breath and attributed the change to the program. One young male noted that he had breathing difficulties and used the breath work he learned to unblock his nasal passages: “One time when I was sleeping, my nose was blocked. So I tried to do the Breath of Fire and it helped me” (fifth grade boy, school 2).

Several youth used a certain breathing technique (kaki) to help relieve stomach aches: “Um, the Kakis really helped because one time I woke up and my stomach was hurting and I did the Kakis and it stopped hurting and then I was fine” (sixth grade male, school 3). Other students used poses to wake up in the morning [“the Sunrise thing because when you wake up and you … it wakes you all the way up so you don’t feel sleepy” (sixth grade female, school 1)] or to alleviate back soreness [“When I woke up and your back is like sore from laying on your side too long, I do the Cobra and I lean back and I hold it for as long as I can I count the alphabet and then let it go. And then that’s fine” (sixth grade female, school 3)].

Frequency of Program Skills Utilization Outside the Program

Two female youths remarked that although they learned the skills and techniques, they did not and will most likely not use the skills outside of the program. One young female described how her family’s entrenched anger was one reason why the techniques did not help her: “No, because I haven’t really done anything. It didn’t help me because I … like I can’t, you can’t breathe through it. ‘Cause my friend makes me angry. My family has bad anger” (fifth grade female, school 2). Program reach may be limited by family context and other factors for some youth. A few students also reported that they did not share the program with anyone outside the program. Reasons given for not sharing lessons learned included not wanting to answer follow-up questions and wanting to keep the information to themselves akin to “what happens in yoga class, stays in yoga class”: “I didn’t show nobody because I think, I think, that like afterwards they’ll ask you like different questions. I didn’t show nobody. They were asking me why I was in the program, and I think that I wanted to keep it, like, to myself. And like whoever was in the program” (fifth grade female, school 1). Some students had a mistaken impression that the instructor did not want them to share material from the program with people outside the program. (Students were, in fact, encouraged to share material, but not personal information regarding other program participants.)

Most students reported using at least one technique outside of the program. The frequency with which youth reported using the techniques ranged from every 2 weeks, on average, to every day the program was offered (twice a week). One fifth grade female taught her cousins (one older and one the same age) breathing techniques and poses after school on the days when she attended yoga (school 2). Some youths remarked that they wanted more structured opportunities to demonstrate their newly acquired skills. One fifth grade female student noted that at the end of the year, she would like to be able to share with other school members what she learned in yoga: “So, everyone in um, make everyone [K-5] go in auditorium and show them what we learnt” (school 2).

Keener Emotional Appraisal and Regulation Skills Promoted Calm and Reduced Stress

Improvements in Emotional Appraisal

Youths reported that the program improved their skills in identifying emotional states of other people and themselves, promoting more positive social interactions. Several students discussed how, through the program, they learned how to identify when other people were experiencing negative emotions (e.g., anger): “So you didn’t bother them in the wrong time. Like say someone in the class got mad about something, you just look at them and be like they are angry don’t bother them right now” (fifth grade male, school 3). Program recipients also learned to notice and anticipate triggers that may escalate these emotions in others. They reported learning to walk away instead of getting into arguments when they recognized these signs in other people. One program recipient remarked: “They [the instructors] tell you when someone is angry and you stay away from them and like don’t make them more [angry]” (fifth grade female, school 3).

New Skills, Calm, and Reduced Stress

Youths also noted the positive psychological benefits of the program, such as assisting with memory, stress, depression, and anger. When describing poses and breathing techniques, students almost always mentioned the stress reduction, calming, and self-regulation benefits of each pose or breath technique. When asked to describe the program, a student reported that the program helped relieve pain, both physical and psychological, by reducing stress: “Releasing stress, umm, maybe releasing pains mentally and physically” (sixth grade female, school 3).

Program psychological benefits were reflected in how youth referred to the program. All students referred to the program as “yoga,” but a few students had their own names for the program: “the land of peace” (sixth grade female, school 1) and the “calm down program” (fifth grade male, school 2). Students learned self-regulation techniques through the program, some of which they believed would be useful when they are older: “I get to learn new stuff and I get to learn about new things and stuff to help me in life, when I grow up like when I’m a young adult, or an older, like in my teens or when I’m, you know, when, when I’m getting’ ready to do something that I know is not the right choice, then I have a way to calm me down” (fifth grade female, school 1) and “like anything that you have problems with you can just use like the things you got taught in yoga to help you” (fifth grade male, school 3).

Youths learned several skills to de-escalate negative emotions, promote calm, and reduce stress. These skills were used in settings outside the program when youth experienced frustration and upset, including the classroom and at home. Some students described strategies for calming down and self-soothing, including having an inner dialog whereby they gave themselves a “pep talk,” trying to forget that upsetting situations occurred (e.g., “Yeah, I go like it never happened”), and removing themselves from the situation and sitting in silence. An example of the latter was noted by a sixth grade male who chose to leave rather than fight peers: “Like if sometimes like I don’t wanna fight them, I be like just, just calm yourself down, just sit down and move away from the situation” (school 2). A male youth noted that when his sisters were causing trouble, he removed himself by going to his room to watch TV, read, or sleep (fifth grade male, school 3). He stated that he was not doing this before the program.

Some program recipients used techniques they learned in the program during test taking in their regular classrooms. Sometimes they practiced these techniques by themselves and other times the entire class practiced the techniques. Youth reported that neck rolls, stretching, and downward facing dog helped them stay awake and calm down during state achievement testing. They would practice stretches, and one sixth grade male described his use of hand gestures to reduce upset during test taking: “First example would be the time when I said I was really frustrated with ahh … with tests and I used the finger thingy” (School 2). Some youth reported feeling more confident and calm about test taking, replacing previous responses of fear and anger as explained by these two fifth graders: “I’m usually scared of tests but I’m like … and then like yesterday on science [State achievement test] I forgot what metal is where, I would usually get mad and just, like I would usually just get mad” (fifth grade female, school 3); “More, confident. Like when some question, when you get like angry ‘cuz you didn’t know something, you know like you are more calm. It made me be more calm” (fifth grade male, school 3).

During breaks in standardized achievement testing at school 3, one intervention student led the class in a short yoga practice for 3 min. This was done across 3 days of testing and the demonstration leader would rotate, being nominated by peers or chosen by the teacher to lead during the breaks. Reflecting on previous years of test taking, prior to these yoga breaks, youth reported they merely sat quietly at their desks, eating snacks, and remembered feeling more tired during the testing: “You are more groggy. Last year we did like that and whenever we had a bathroom break, everybody just sat down and sat there and no one even talked. We just sat there and ate” (fifth grade male, school 3). But, now the yoga break has helped to make test taking more positive; they are “happier to do it. Happier to like do the test … more, ahh, more confident” (fifth grade male, school 3).

Youth and Teacher Expectations for Immediate and Future Program Impact

Overall, youths and teachers reported cautiously optimistic expectations for the program to positively impact youths’ stress levels and behaviors during the program and beyond. Teachers specifically reported on classroom observations of youths applying new skills learned during the program.

Youth Optimism for Future use of Skills

Youths were optimistic about future use of the skills they learned in the program. One male spoke about how yoga could prevent a negative outlook on life: “I could use them [program skills] in the future because when you get older more things will happen so you will get more stressful and you’ll think life is like over so you might wanna learn yoga before that happens” (sixth grade male, school 2).

Other students described the physical benefits of yoga that will help them in the future. One female spoke about how yoga—the sunrise salutation in particular—will help preserve good posture in the back and prevent the bent back she sees in older people: “Like, they say that how the old people their like back is like that [bent] and if you keep on doing the Sunrise, it won’t be bent like that” (sixth grade female, school 1). In the future, one male said he would use breathing techniques to help with stomach aches and the fountain of youth would benefit him when he gets older: “Like Kaki for stomachaches … and when you get older you can do the Fountain of Youth. When you get older and get body aches and stuff like that … Help you feel, uh, make you feel younger … Help your body like rest” (fifth grade male, school 3).

Some youths remarked that the program needed to be longer in duration to help them use skills in the future. For example, one youth pointed out that at the end of the program, they were taught a 20-step sequence, from which she could not even remember one step: “We have to do the program more. We have a long way to go. I still have my anger issues too …. Like he showed us 20 steps at the very end and I don’t even remember one of them out of the 20.” (school 3). Overall, program recipients appeared to believe that the skills they learned through the program had broad utility. One particularly poignant comment about the positive influence of yoga was offered by a sixth grade male: “You should always go to yoga … it teaches you everything about how to have a really great life” (sixth grade male, school 2). Another student spoke about long-term life lessons the program conveyed: “It’s like peaceful. And relaxing. It teaches you life lessons that you could use in the future” (sixth grade female, school 1).

Teacher Expectations of Program Effects

At the start of the program, many teachers reported they did not have specific expectations about program influences on youth because they were unaware of program goals. Yet, they hoped the program would positively impact youths’ stress levels and classroom behaviors. As one male sixth grade teacher reported: “I wasn’t sure what I expected, to be honest with you” (school 2); yet he had hoped to see positive changes. Both teachers at school 1 thought the program was a good idea because of its potential to help youth and improve their behavior: “I thought it was a good idea. Something to help them. Help them with behavior and stuff like that” (female sixth grade teacher). Several teachers mentioned youths’ hormones having negative effects on behaviors and stress levels in the classroom and hoped youth would learn breathing techniques to help them cope with hormonal changes and reduce friction and stress in their lives and the classroom.

Most teachers had realistic expectations that any positive changes in youth would take time to manifest. For instance, one male sixth grade teacher remarked that he did not expect immediate change: “I didn’t expect changes overnight. I knew it would take some time” (school 2). They expected to see gradual changes in students by the end of the year as described by another sixth grade male teacher: “Well, I figured by the end of the year I’d start seeing some changes and I have especially, as I said, with the students who exhibited the worse [behavior]” (school 2).

Other teachers had high expectations for program effects translating into major improvements in classroom behavior and focus that were not fulfilled. For example, a female sixth grade teacher described:

Um, yeah, I thought that it would be something that would help them in class like with their behaviors and stuff like that. But, um, it wasn’t. I didn’t see any change, any improvement in anyone’s behavior …. I just imagined that the children would be more behaved … So, I just thought maybe that that would have been curbed more and that they would be focus themselves. But it was the same way. They still lacked focus (school 1).

Another sixth grade teacher had high hopes that the program “would teach them how to, um, deescalate a situation. But it didn’t” (school 1).

Observed Changes in the Classroom

Several teachers observed program youths applying program skills in the classroom. Some teachers reported positive changes they witnessed in the classroom and attributed it to the program. One male sixth grade teacher reported hearing youths sharing—without any prompting—what they learned during the sessions with classmates who were not in the program: “I actually overheard some students sharing with other students some techniques. I think … they were saying that it was something they learned about themselves. I thought it was a good thing they were willing to share with other classmates” (school 2). This teacher described different types of calming techniques and hand gestures, which he was able to learn from what he overheard from the students.

Several teachers were pleasantly surprised when they witnessed unanticipated changes in some youth. For example, one fifth grade teacher remarked that, as a result of the program, a shy student unexpectedly assumed more leadership: “It wasn’t my expectation for example that [Student] would be thrilled to be up at the front of the class and talking the kids through the moves. I mean [Student]’s brilliant, so I’m not surprised, I just wasn’t prepared for that” (school 3). Increased confidence among some program youth was noticed by classroom teachers and was evident in how comfortable students felt sharing in the classroom what they learned from the yoga program. Youths’ experience “leading something” during the yoga program helped boost their confidence which, in turn, translated into better performance in the classroom (e.g., when they needed to present in front of the class, they were calmer and their delivery was smoother) and more participation (raising their hands to contribute in the classroom) as described by a female fifth grade teacher:

I think a few students gained more confidence from it, being in a smaller group setting was something that, other than academics, where they were able to lead something and it’s in a calm and relaxed environment and then they came into the class. I felt the students who would sometimes get nervous when they had to speak in front of the class and may stutter at times, they would speak more slowly and calm down their voice a little bit… They felt more confidence—started raising their hands during class. (school 2)

Changes seemed more pronounced for youths who started the program with limited self-regulation skills at the beginning of the program. Teachers reported that these youths were noticeably calmer after the program. One teacher attributed positive changes to the intimate, relaxed, and calmer environment afforded by the yoga class, which removed youths—at least for a short time—from the larger and more chaotic academic class. One comment by a sixth grade male teacher describes how a student who reacted to frustration and stress with anger prior to the program was now reacting with greater calm:

I noticed a big change in—not the students who basically handled themselves okay in the beginning …— but the students who struggled with it. You know I had a couple of students in the beginning that they had a hard … they’d blow up … a temper … tended to have a very short fuse. They had to walk out of the classroom. Now whenever I see them their face was calm in a similar situation … they handled it a lot better. A lot calmer. My guess is that the program is partly responsible for that … A lot of those students were known to just get up, throw her table and chair to the side. Send it flying and walk out. That’s the way she normally reacted to the problems. This time she was in a situation where I knew how she would have reacted in September and October, this time she put her head down like this … Then she went like this and then a few minutes later she was fine. (school 2)

The program was perceived as a beginning step in a positive behavioral change trajectory by some teachers, who noted that continuing the program over several years and starting at younger ages may be necessary for producing lasting effects. As one fifth grade female teacher described, sometimes program youths referred to aspects of the program like the breathing techniques and poses. But, she was uncertain how much they practiced outside the program because practice in the classroom was rare: “I think some kids occasionally remembered to use some of the yoga breathing. They talked, you know, ‘I know what to do and I know to roll my neck’ and all of this but I’m not sure how much they did it. But it was a beginning” (school 3). This same teacher reported students did use their skills during testing once or so, but they often forgot to include it. “I think it’s great! We used it during MSA. We didn’t remember to use it a lot of other times. Occasionally we would say when they were angry ‘Use your yoga breathing’” (fifth grade female teacher, school 3).

Other teachers, particularly at school 1, reported not observing any changes in their students who attended the program. Yet, they believed the program could be useful for teachers in the classroom to create an environment more conducive to learning: “It may make them better behaved. Like you know, know when it’s time, when and where is the time to play and it’s not the classroom. They are wasting valuable time with all this horseplay and they are missing instruction that they need in life” (sixth grade female teacher, school 1). Another sixth grade teacher (school 3) provided insight into why she had a difficult time noticing any changes in her sixth grade students, describing hormonal changes, difficult social interactions, and unfocused minds as developmental challenges to observing positive changes: “I didn’t notice that much of a change. With sixth grade it’s hard to see a change… But sixth graders, their minds are already jumping off the walls everywhere.” Indeed, “no change” may be a positive result if decreases in good behavior (e.g., fighting, resistance to authority) are expected during pubertal maturation. She was encouraged, however, to see changes in the current fifth graders receiving the program, whom she would have in class in the fall as sixth graders.

Teachers’ Cautious Optimism about Future Skills Use by Youths

Teacher perceptions varied regarding whether the youths would continue to show positive changes as a result of the skills they learned in the yoga program. Some teachers were optimistic about sustainable changes for the youths, saying the youths had an experience that would remain with them for life. Most teachers noted that the program was positive for the youth, with some teachers being more enthusiastic than others. Some teachers were less optimistic about students’ future use of program skills, however, pointing out that summer break was soon approaching and would result in youths reverting back to past patterns due to lack of practice. One male teacher stated: “I guess. I don’t know what’s going to happen over the summer … Two to three months of not practicing it …” (sixth grade male teacher, school 2). A female fifth grade teacher was cautiously optimistic, noting that positive change would be sustained if youths followed through with a consistent and continuous practice through high school and college. She remarked that despite summer break, exposure to the program should have future effects because it is an experience youths would have for life: “I think exposure. I don’t think you are going to see immediate changes with some things. But with most things in life, what I think is the exposure alone to something other than their norm will definitely produce some sort of life change. You know just their being exposed to yoga, the [times] that’s behind it. You know the history of it. … It’s an experience they’ll have with them forever” (fifth grade female teacher, school 2).

Teachers expressed different views about the types of students who might benefit most from mindfulness and yoga. A sixth grade teacher who had reservations about yoga and mindfulness questioned whether the program would be effective with urban, disadvantaged youths. A few teachers remarked that the breathing and other calming techniques taught in the program may have future benefits for specific youths—youths with infrequent, small anger outbursts—and less “rambunctious” youths. A sixth grade female teacher (school 1) noted that the program may have future effects on youths who approached the program with an open mind and expressed the belief that her students did not have an open mind about the program. Another sixth grade teacher thought the program could have positive effects (e.g., using breathing techniques to calm down: “If they’ve got those breathing patterns and they know how to do it”—school 3) for a broader group of youths if the program started in earlier grades and was implemented over a longer time period and over multiple years or grades (e.g., into seventh grade).

Discussion

Four major themes emerged from our discussions with students and teachers. First, some learning and application of program skills occurred, with youths reporting practicing skills outside the program, and most teachers validating that this learning translated into the classroom both spontaneously (teachers overheard youth sharing their skills with classmates) and during structured times (when students demonstrated these skills to the entire class during MSA testing breaks). Second, as a result of the program, youths made linkages between techniques, health benefits, and real-life applications, which they shared with others. Third, youths reported improved emotional appraisals of self and others, as well as enhanced and new skills that helped promote positive social interactions. Last, both students and teachers generally voiced positive expectations about the program’s potential for beneficial effects on youth.

Although schools varied with respect to average student program attendance (range=38–86 % of sessions, Table 2; for details see Feagans Gould et al. 2014), all focus group youth—even those who reported they did not use skills outside the program—described a skill or technique taught in the program, suggesting that learning occurred across the entire focus group sample. With few exceptions, youth applied program skills either in the classroom, at home, or in both settings. Students did not systematically vary across schools in their degree of positive or negative reports about the program.

Our findings are generally encouraging with respect to student retention and use of program skills. Student and teacher comments, however, raise a number of critical—still unanswered—questions about implementation of school-based mindfulness and yoga programs. How much program exposure is optimal or sufficient for learning to occur? Several students and teachers believed offering the program over more than 1 year would be necessary for producing meaningful changes, but we do not yet have data to indicate that this is the case. Indeed, the emerging field of school-based mindfulness and yoga research does not yet have empirically based recommendations regarding dosage (Cook-Cottone 2013; Feagans Gould et al. 2015). At which ages are youths most likely to be receptive to mindfulness and yoga? Some teachers in our focus groups believed that the hormonal changes occurring during sixth grade made this a more difficult time to intervene, whereas others did not share this opinion. Which types of youths are most likely to experience benefits from mindfulness and yoga? Teachers expressed divergent viewpoints, with some noting that they saw the greatest positive growth in students with higher levels of behavioral problems and others suggesting that the program is more likely to benefit students without significant behavioral issues. The diversity of teacher opinions on these points highlights the complexity of the questions. Gathering longitudinal data from students and teachers in school-based mindfulness intervention studies has potential to shed some light on these issues, in combination with analyses of participant characteristics that moderate intervention outcomes (e.g., baseline behavior problems; baseline age). These are key questions for future study and have potential to advance the field of school-based mindfulness and yoga research in substantive ways.

Our findings also have implications for the delivery of mindfulness-based programs in the context of broader educational practices and policies. The current study focused on providing mindfulness and yoga to students; but feedback from teachers indicated that many would have appreciated more information and involvement in the program, particularly regarding ways to prompt students’ skills generalization in class. The teachers and students in classrooms in which students practiced breathing techniques during state testing reported positive experiences with this approach. This suggests that future program implementation should carefully consider involving teachers more explicitly in learning program skills and creating classroom-based opportunities to promote skills. Teachers’ concern that students may forget program skills can also potentially be addressed by integrating skills use into the classroom on a regular basis, even after the program has ended.

Integration of mindfulness and yoga concepts and skills into the educational context may take a number of different forms. For instance, youths’ apparent interest and detailed recall regarding health benefits of mindfulness and yoga suggest mindful yoga programs may be integrated with academic coursework in biology, physiology, and health, or these concepts can potentially be incorporated into mindful yoga programs to reinforce subject-level learning. Youths found particularly meaningful the lessons that had real-life applicability such as how breath work aided their athletic pursuits (e.g., sports, gym class) and the utility of poses and breath work to address health conditions. Learning about health benefits of breath work and poses motivated youth to practice program skills outside the program and share their knowledge with others, further reinforcing their learning. Future studies examining how to integrate mindfulness skills learning with academic lessons have potential to advance program development and promote sustainability of such programs in school settings.

Other approaches to skills integration include promotion of prosocial behavior and focused attention in the classroom. Teachers familiar with intervention techniques could prompt students’ use of skills, such as deep breathing, at the beginning of the day as a foundation for learning and at transitional points, such as following lunch. Teachers could also prompt skills use to encourage students to manage difficult emotions, such as anxiety prior to a test or anger during a difficult interaction with a teacher or peer. Responses from students and teachers suggested that skills generalization occurred sporadically in the current study, highlighting the potential benefit of modifications to intervention delivery—including enhanced teacher involvement—to promote more robust and consistent use of skills across school contexts. Learning about health benefits of breath work and poses motivated youth to practice program skills outside the program and share their knowledge with others, further reinforcing their learning.

Qualitative data from students and teachers has potential to enrich our understanding of intervention core components and mechanisms of action, as well as informing the selection of appropriate outcome measures. Regarding core components, our findings suggest that students had detailed knowledge of yoga-based poses and breathing techniques, both core program activities. Students did not explicitly mention discussion of major topics, another core activity, although student knowledge about the emotional and physical benefits of yoga reflected many of the discussion topics covered. It may be worth exploring in future work whether certain discussion topics (e.g., practicing compassion; respect for the environment) were not retained to the same degree as the poses and breath work, and, if so, whether those topics could be more consistently mentioned or more closely linked with the poses or breath. The degree to which discussion topics were mentioned by youth may also reflect the way that focus group questions were worded. Other program components, such as homework practice and in-class review, while not mentioned explicitly by students, very likely contributed to student retention of material. Researchers studying school-based mindfulness interventions may find that it is useful to obtain qualitative feedback from students and teachers in order to identify which program core components are most salient or best understood by students. This knowledge may lead to modification or refinement of how core components are delivered, or may provide additional support for the hypothesized components.

Qualitative feedback from students and teachers can also help to generate or support hypotheses regarding intervention mechanisms of action. The conceptual model that informed the current study proposed that mindful yoga would influence youth social-emotional and behavioral functioning via improved emotional and cognitive regulation (Mendelson et al. 2010; Feagans Gould et al. 2014). Results from this study tend to support that model, suggesting students learned and retained skills that promoted greater emotional regulation; it is important, however, that we also evaluate whether quantitative findings corroborate the qualitative accounts. Across settings, students mentioned that they were increasingly able to remove themselves from upsetting situations or otherwise manage their emotions in order to calm down. These sorts of statements support improved self-regulation as a key process on the pathway of change, as we and others have hypothesized (Brown and Ryan 2003; Mendelson et al. 2010; Zenner et al. 2014). Students in our sample also reported that the program helped them to better appraise their own emotional states and those of other people. Improved emotional appraisal is consistent with—but also extends—the change pathway outlined in our program conceptual model. In addition, our data suggested that students took an active role in teaching others program skills, and at least one teacher noted improved participation and leadership ability in one or more students. Based on these comments and discussion with the intervention developers, our team has recognized that promotion of self-efficacy and leadership may also be relevant to intervention mechanisms of change. In the early stages of intervention research that characterize most current work on school-based mindfulness and yoga programming, qualitative feedback is extremely valuable for generating ideas that can expand, modify, or further elaborate heuristic models of intervention components and mechanisms.

Qualitative data can also inform the selection and development of appropriate quantitative outcome measures. Our data suggest that it may be worthwhile to include measures of student knowledge of intervention core activities (e.g., breathing techniques), as well as measures of when and how students practice program skills, as both are proximal outcomes that may potentially be relevant for emotional and behavioral change. Students in our sample also mentioned anger as an emotion they frequently struggled with and which program skills helped them manage. Including measures of youth anger and strategies for managing anger will be important in future research on this intervention. Quantitative measurement of newly identified proximal outcomes or mechanisms of change, including emotional appraisal and self-efficacy, may also prove important. Ultimately, the use of qualitative and quantitative methods and data in combination can provide a rich perspective on how an intervention influences various aspects of youth functioning and development. Quantitative measures can serve to assess domains that are mentioned in qualitative work; qualitative feedback can augment our understanding of quantitative findings as well as suggest ways to expand or modify quantitative measures so as to more effectively capture student experiences. Given the newness of research on school based mindfulness and yoga, it is particularly critical that we incorporate qualitative and mixed methods into our work to inform ongoing intervention development and evaluation.

This study has a number of limitations. We acknowledge it is important that we not overstate benefits of mindful yoga based on one study. Our findings are based on a single mindful yoga program implemented in three different schools by different instructors and may not generalize to other programs or students. Given the voluntary nature of this study, it is possible that students who assented and who received parental consent to participate in the program are systematically different from youth who did not. For instance, program youth may be more motivated to learn skills; alternatively, it is possible that parents were more likely to enroll youth with behavioral problems. In one school, only sixth grade teachers participated in the focus groups due to scheduling conflicts and lack of availability. We did not select a random sample of intervention participants for focus groups due to logistical constraints; teachers, however, were asked to identify participants with a range of demographic characteristics and varied levels of program attendance and engagement. Heterogeneity among youth reports was obtained, providing greater confidence that selection effects were reduced. These data were collected shortly after the program ended, capturing immediate post-test effects; longer-term perspectives, however, were obtained using qualitative methods.

This study has several strengths. First, the study included the voices of elementary and middle school youth (fifth and sixth graders), whereas previous qualitative studies on mindfulness and yoga have primarily examined experiences of high school students and college-aged youth (Sibinga et al. 2011, 2014; Tharaldsen 2012). Second, this study included classroom teachers who were not directly involved in the program as secondary informants, providing a separate perspective on skills youth learned and applied. Teachers’ observations were consistent with students’ reports and were generally supportive of the program’s intended aims. Third, the focus groups and interviews elicited process—rather than exclusively outcome—data from youths and teachers, adding to the literature an exploration of what skills program recipients recalled and whether the lessons translated into practice in “real life” settings (e.g., home, classroom). Last, teachers and students participating in this study represent an understudied population, teaching in and attending schools in impoverished and disadvantaged environments.

Future studies would benefit from multiple qualitative assessments that extend beyond immediate post-test to evaluate the extent to which skills are retained, sustained, and further developed over time. Such data would address the mixed finding whereby some teachers perceived youths would lose the skills if they were not used over the summer whereas other teachers anticipated youths’ benefits would sustain over time. Longitudinal qualitative data collection could complement follow-up quantitative assessments and may suggest additional ways in which the program influences students over time. Triangulation of multiple key stakeholder reports (program implementers, program recipients and their parents, classroom teachers, and school administrators) would also provide even more context for understanding youth skills use and contextual program effects. Parent or other family member reports could verify the extent to which youth used program skills outside school. School administrators’ perspectives may yield insight into potential for grade-wide, and school-wide, behavioral and climate changes.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Conflicts of Interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PC, Metz S. Learning to BREATHE: a pilot trial of a mindfulness curriculum for adolescents. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2009;2(1):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(4):822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion J, Rocco S. Minding the mind: the effects and potential of a school-based meditation programme for mental health promotion. Advances in school mental health promotion. 2009;2(1):47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Case-Smith J, Shupe Sines J, Klatt M. Perceptions of children who participated in a school-based yoga program. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2010;3(3):226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Conboy LA, Noggle JJ, Frey JL, Kudesia RS, Khalsa SBS. Qualitative evaluation of a high school yoga program: feasibility and perceived benefits. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2013;9(3):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Cottone C. Dosage as a critical variable in yoga therapy research. International journal of yoga therapy. 2013;2(2):11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Lee K. Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science. 2011;333(6045):959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1204529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagans Gould L, Mendelson T, Dariotis JK, Greenberg MT. Assessing fidelity of core components in a mindfulness and yoga intervention for urban youth: applying the CORE process. New Directions for Youth Development. 2014;142:59–81. doi: 10.1002/yd.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagans Gould L, Dariotis JK, Greenberg MT, Mendelson T. Assessing fidelity of implementation (FOI) for school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions: a systematic review. Special issue on School-based mindfulness interventions. Mindfulness. 2015:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s12671-015-0395-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: measurement issues and prospective effects. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(2):412–425. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Harris AR. Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: current state of research. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;6(2):161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SBS, Hickey-Schultz L, Cohen D, Steiner N, Cope S. Evaluation of the mental health benefits of yoga in a secondary school: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2012;39(1):80–90. doi: 10.1007/s11414-011-9249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagor AF, Williams DJ, Lerner JB, McClure KS. Lessons learned from a mindfulness-based intervention with chronically ill youth. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology. 2013;1(2):146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T, Greenberg MT, Dariotis JK, Feagans Gould L, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz SM, Frank JL, Reibel D, Cantrell T, Sanders R, Broderick PC. The effectiveness of the learning to BREATHE program on adolescent emotion regulation. Research in Human Development. 2013;10(3):252–272. [Google Scholar]

- Monshat K, Khong B, Hassed C, Vella-Brodrick D, Norrish J, Burns J, Herrman H. A conscious control over life and my emotions:” mindfulness practice and healthy young people. A qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(5):572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noggle JJ, Steiner NJ, Minami T, Khalsa SBS. Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-being in a US high school curriculum: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2012;33(3):193–201. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824afdc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadusky BJ. Maryland report card 2011 performance report state and school systems. Maryland State Department of Education; 2011. [Accessed 21 November 2014]. http://dlslibrary.state.md.us/publications/Exec/MSDE/ED7-203%28e%29_2011.pdf.mdreportcard.org. [Google Scholar]

- Serwacki ML, Cook-Cottone C. Yoga in the schools: a systematic review of the literature. International journal of yoga therapy. 2012;22(1):101–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EM, Kerrigan D, Stewart M, Johnson K, Magyari T, Ellen JM. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for urban youth. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2011;17(3):213–218. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibinga EM, Perry-Parrish C, Thorpe K, Mika M, Ellen JM. A small mixed-method RCT of mindfulness instruction for urban youth. EXPLORE: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2014;10(3):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP. Developmental neurobiology of childhood stress and trauma. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;25(2):397–426. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(01)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharaldsen K. Mindful coping for adolescents: beneficial or confusing. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion. 2012;5(2):105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Weare K. Developing mindfulness with children and young people: a review of the evidence and policy context. Journal of Children’s Services. 2013;8(2):141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wisner BL. An exploratory study of mindfulness meditation for alternative school students: perceived benefits for improving school climate and student functioning. Mindfulness. 2013:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zenner C, Herrnleben-Kurz S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5(603):1–20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoogman S, Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT, Miller L. mindfulness interventions with youth: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2014:1–13. [Google Scholar]