Abstract

Background

Pemphigus is a potentially life threatening autoimmune disease that causes blisters and erosions of the skin and the mucous membrane. The epithelial lesions are a result of auto-antibodies that react with desmosomal glycoproteins that are present on the cell surface of the keratinocyte. The autoimmune reaction against these glycoproteins causes a loss of cell to cell adhesion, resulting in the formation of intraepithelial bullae. Eighty to ninety percent of patients with pemphigus vulgaris develop oral lesions and in 60% of cases oral lesions are the first sign. Timely recognition and therapy of oral lesion is critical as it may prevent skin involvement. If treatment is instituted during this time, the disease is easier to control and the chance for an early remission of the disorder is enhanced.

Case Details

This case report describes the case of a patient who complained of ulcers of the mouth and difficulty in swallowing since 20 days, who was diagnosed as having Pemphigus vulgaris. Due to early diagnosis, lower doses of medication for a shorter period of time could control the disease.

Conclusion

Dental professionals must be sufficiently familiar with the clinical manifestations of pemphigus vulgaris to ensure early diagnosis and treatment which in turn determines the prognosis and course of the disease.

Keywords: Pemphigus, oral lesions, mucous membrane, chronic oral ulcers, pemphigus vulgaris

Introduction

Pemphigus is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune bullous disease. There are 0.5 to 3.2 cases reported each year per 100,000 population, with the highest incidence in the 5th and 6th decade of life, with male to female ratio of 1:2. (1). Some rare cases have been reported in children and the elderly (2). The major variants of pemphigus are pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematosus, paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) and drug related pemphigus. Pemphigus Vulgaris is the most common form of pemphigus, accounting for over 80% of cases (3). In the majority of patients, it affects the oral mucosa and is sometimes difficult to diagnose when only mucosal involvement is present.

Lesions may occur anywhere on the oral mucosa, but the buccal mucosa is the most commonly affected site followed by involvement of the palatal, lingual and labial mucosa. Gingiva is the least commonly affected site and desquamative gingivitis is the commonest manifestation of the disease when gingival is involved (3). In many patients, oral lesions are followed by the development of skin lesions (4,5). If oral pemphigus vulgaris can be recognized in its early stages, treatment may be initiated to prevent the progression of the disease to skin involvement. Diagnostic delays of greater than 6 months are common in patients with oral pemphigus vulgaris (6). The oral cavity may be the only site of involvement for a year or so, and this may lead to delayed diagnosis and inappropriate treatment of a potentially fatal disorder. This case report describes the case of a patient complaining of ulcers in the mouth and difficulty in swallowing since 20 days, who was diagnosed as having Pemphigus vulgaris.

Case Report

A 40-year-old male patient resident of Karwar, Karnataka, reported with the chief complaint of ulcers in the mouth and difficulty in swallowing solid food and liquids since 20 days. History revealed that the patient first noticed dysphagia for solid food which progressively increased in severity. At the time of presentation, the patient had dysphagia for liquid as well. The patient had noticed ulcers of the mouth which bled on brushing, and increased salivation in the morning was reported. The patient did not report of skin lesions or involvement of other mucosal sites. A review of medical and family history was noncontributory. The patient had poor oral hygiene with adverse habit of taking betel quid with tobacco 10 times daily and smoking 35 bidis per day since 10 years. He was also habit of alcohol consumption of 2 quarters per day from last 10 years.

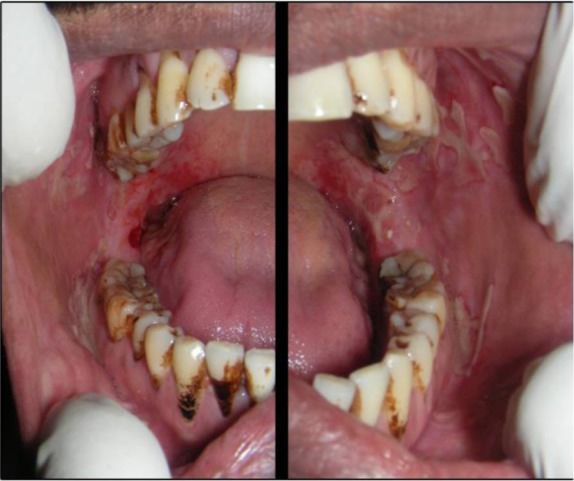

On general examination, the patient was moderately built and signs of anemia were present. Submandibular lymph nodes were enlarged, palpable and tender bilaterally. Intra-oral examination revealed ulcerative lesions present on bilateral buccal mucosa along the line of occlusion extending from retrocommisural areas to the retromolar trigone posteriorly (Figure 1). Lesions extended superiorly from the line of occlusion and were irregular in shape covered by pseudomembrane with erythematous surrounding. On manipulation, bleeding was present. Similar lesions with irregular borders associated with flaacid bullae were present in the lower buccal vestibule in relation to molar region. Lesions were also present posteriorly on the lateral border of the tongue on left side. Erosive lesions were seen involving posterior hard plate, soft palate, faucial pillars and extending to the oropharynx (Figure 2). There were diffuse areas of erosions covered by pseudo membrane at some sites. Nikolysky's sign showed a positive reaction. Generalised teeth attrition and gingival inflammation with bleeding on probing were present.

Figure 1.

Intra-oral photograph of the patient showing ulcerative lesions present on bilateral buccal mucosa along the line of occlusion; the lesions with irregular borders associated with flaacid bullae in lower buccal vestibule in relation to molar region seen

Figure 2.

Intra-oral photograph of the patient showing erosive lesions involving posterior hard plate, soft palate, faucial pillars and extending to the oropharynx

The clinical presentation of chronic multiple oral ulcers, flaccid bullae and positive Nikolysky sign in this case led to provisional diagnosis of vesiculo-bullous lesion affecting the oral cavity. Differential diagnosis included pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, para neoplastic pemphigus, chronic ulcerative stomatitis, recurrent herpes lesions in immunocompromised patients and erythema multiforme.

Routine haematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits except haemoglobin of 9.5mg%. Incisional biopsy was performed from peri lesional site of the right buccal mucosa. Histopathological examination revealed parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with intra-epithelial blister formation. Split area was covered by thick area of fibrinous exudate consisting of inflammatory cells. Occasional giant cells (Tzank cells) were seen in the split area. Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the sub epithelial and perivascular region was evident (Figure 3). Based on the histopathological findings, a final diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris was made.

Figure 3.

Photomicrograph (X40, Hematoxylin and eosin stained) showing parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with intra-epithelial blister formation; occasional giant cells seen in the split area; chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in the sub epithelial and perivascular region evident.

The treatment plan comprised oral prednisolone 60 mg/day for 4 days along with multi-vitamin and analgesic. Topical analgesic mouthwash and 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide ointment were also prescribed to the patient. On the first follow-up, the patient had 50% reduction in symptoms with partial healing of lesions, erythema and inflammation in relation to ulcers had reduced (Figure 4). The dose of Wysolone was tapered to 40 mg/day for the next four days. On second follow-up, 20% reduction in symptom compared to the first follow-up was noticed. The number of lesions reduced. Biopsy site healed. Suture removal was done and prednisolone dose was tapered to 20mg/day for 4 days. On the third follow-up, 90% reduction in symptom was noticed; lesions healed almost completely (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Intra-oral photograph of the patient showing reduction in the size of the lesions and reduction in the erythema and inflammation associated with it

Figure 5.

Intra-oral photograph of the patient showing almost complete healing of ulcerative lesions.

Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare cause of chronic ulceration of the oral mucosa. The mouth may be the only site of involvement for a year or so. In this case, early diagnosis and lower doses of medication for shorter period of time was could control the disease.

Discussion

Pemphigus is defined as a group of life threatening blistering disorder of skin and mucous membrane characterized by acantholysis (loss of keratinocyte to keratonicyte adhesion). The process of acantholysis is induced by circulatory autoantibodies to intercellular adhesion molecules (6). In most cases (70–90%), the first sign of the disease appears on the oral mucosa. While the lesions can be located anywhere within the oral cavity, they are most commonly found in areas subjected to frictional trauma such as the cheek mucosa, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, genital mucosa as well as the skin where intact blisters are commonly seen (7).

The major variants of pemphigus are pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus erythematous, paraneoplastic pemphigus and drug related pemphigus. Each form of this disease has antibodies directed against different target cell surface antigen, resulting in a lesion forming in different layers of the epithelium (8). Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common form of pemphigus, accounting for over 80% of cases (5).

The underlying mechanism responsible for causing the intraepithelial lesions of pemphigus vulgaris is the binding of Ig G autoantibodies to desmoglein 3, a transmembrane glycoprotein adhesion molecule present on desmosome. The binding of Pemphigus Vulgaris antibody activates protease, whereas more recent evidence support the theory that the Pemphigus vulgaris antibodies directly block the adhesion function of the desmoglein (9, 10, and 11 The separation of cells called acantholysis takes place in the lower layers of stratum spinosum, which results in the formation of suprabasilar bulla. The bulla increasingly involves a larger area of epithelim, resulting in loss of large area of skin and mucosa.

The classical lesion of pemphigus is a thin walled bulla arising on otherwise normal skin or mucosa. A characteristic sign of the disease may be obtained by the application of pressure to intact bullae. In a patient with Pemphigus Vulgaris, bullae enlarges by extension to an apparently normal surface. Another characteristic sign of the disease is the pressure to apparently normal area resulting in the formation of a new lesion. This phenomenon, called Nikolysky sign, results from the upper layer of the skin pulling away from the basal layer. Nikolysky sign is also found to be positive in toxic epidermal necrolysis, scalded skin syndrome (both of which are acute conditions) and mucous membrane pemphigoid (12).

If proper history is taken, the clinician should be able to distinguish the lesions of pemphigus from those caused by acute viral infections like herpes and erythema multiforme. Immunocomprised patients present with recurrent herpetic simplex infections in the form of atypical ulcers, which may last several weeks or months if undiagnosed and untreated. Moreover, the presence of Tzank cells may complicate the diagnosis. Since in the present case, the patient did not give history of immunocompromise like chemoptherapy, organ transplant or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, recurrent herpes simplex infection could be safely ruled out.

Differential diagnosis of Pemphigus Vulgaris can be done from other similar conditions by biopsy and direct immunoflorescence. Biopsies are best done on intact vesicles and bullae less than 24 hours old. The biopsy specimen should be taken from the advancing edge of the lesion, where the area of characteristic suprabasilar acantholysis can be observed by the pathologist. Supra basilar split seen in Pemphigus Vulgaris helps distinguish this condition from sub-epithelial blistering diseases such as mucous membrane pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus and chronic ulcerative stomatitis. Indirect immunoflorescence is helpful in further distinguishing pemphigus from pemphigoid and other chronic oral lesions and is useful in following the progress of patient for pemphigus. The diagnosis is confirmed by the characteristic deposition of IgG and other C3 antibodies that bind to cell surface of perilesional skin or mucosa (13,14). Indirect immunoflorescence is less sensitive than direct immunofluorescence, but may be helpful if biopsy is difficult. ELISA has been developed that can detect desmoglein 1 and 3 in serum sample of patients with Pemphigus Vulgaris (14). The presence of anemia and submandibular gland lymphadenopathy along with painful stomatitis and acantholysis on histopathological investigations in the present case led to the differential diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Absence of underlying lymphoproliferative disorder, the reduced severity of the lesions and absence of inflammation at the dermal-epidermal junction and keratinocyte necrosis in addition to characteristic acantholysis helped rule out this condition. Also, direct immunoflorescence of para neoplastic pemphigus shows deposition of IgG and complement along the basement membrane as well as on the keratinocyte surface in an intercellular location (15).

An important aspect of patient management is early diagnosis when lower doses of medication can be used for shorter periods of time to control the disease. Dental professionals must be sufficiently familiar with clinical manifestation of pemphigus vulgaris to ensure early diagnosis and treatment, since this in turn determines the prognosis and course of the disease. Institution of early treatment could prevent serious involvement of other mucosa and cutaneous sites and fatal complications. Pemphigus Vulgaris is generally managed with local and systemic corticosteroid therapy. Treatment is administered in 2 phases: a loading phase, to control the disease, and a maintenance phase, which is further divided into consolidation and treatment tapering. Local treatment consists of a paste, an ointment or a mouthwash administered alone or in conjunction with systemic treatment. Intralesional injections of corticosteroids have been used for the management of persistent lesions (16). In cases of extensive oral lesions or involvement of other mucosa and skin, systemic corticosteroid therapy is initiated immediately. The initial of prednisone 0.5–2 mg/kg is recommended (17). Depending on the response, the dose is gradually decreased to the minimum therapeutic dose, taken once a day in the morning to minimize side effects. When steroids are used for longer periods of time, adjuvants such as Azathioprine or Cyclophosphamide are added to the regimen to reduce the complications of long term corticosteroid therapy. Before the advent of corticosteroid therapy, pemphigus was fatal, with a mortality rate of up to 75% in the first year. It is still a serious disorder, but the 5% to 10% mortality rate is now primarily due to the side effects of therapy (18).

References

- 1.Shamim T, Varghese VZ, Shameena PM, Suddha S. Pemphigus Vulgaris in oral cavity. Clinical analysesof 71 cases. Med Oral Pathol Buccal. 2008;13:2622–2626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DM. Vesiculobullous Mucocutaneous Disease: Pemphigus Vulgaris. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989;18:544. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scully C, Paes De Almeida O, Porter SR, Crilkes JJH. Pemphigus Vulgaris, manifestations and long term management of patient with oral lesions. British Journal of Dermatology. 1999;140(1):84–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kauvsi S, Danesh pazhooh M, Farahani F, Abedini R, Lajevardi V, Chams davatchi C. Outcome of Pemphigus Vulgaris. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2008;22(5):580–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo H, Rees TD, Hallmon WW. Disease progression from mucosal to mucocutaneous involvement in a patient with desquamatous gingivitis area with Pemphigus Vulgaris. Journal of Periodontology. 2008;99(2):368–375. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michael H, Carrian S. Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestation and diagnosis of Pemphigus. 2013. Jul 7, url: http//www.uptodate.com/store.

- 7.Dagistan S, Goregen M, Milogluo, Lakur B. Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Case Report with review of literature. J Oral Sci. 2008;80:359–362. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huntley AC. Pemphigus Vulgaris and vegetating and verrucous lesions. Case Report, Dermatol Online J. 2004:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahoney MG, Wang Z, Rothenberger K. Explanation for the Clinical and Microscopic localization of lesion in Pemphigus foliaceous and vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:461–468. doi: 10.1172/JCI5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen PJ, Barad J, Morioka S. Epidermal Plasminogen activator is abnormal in cutaneous lesion. J Invert Dermatol. 1988;90:777. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12461494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanley Cell adhesion molecule as target of autoantibodies in pemphigus and pemphigoid bullous due to defective cell adhesion. Adv immunol. 1993;53:291–393. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urbano FL. Nikolsky's Sign in Autoimmune Skin Disorders. Hospital Physician. 2001:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kancoar AJ, Deo Pemphigus in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereai leprol. 2011;77:439–449. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.82396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM British Association of Dermatologists, author. Guideline for the Management of pemphigus Vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anhalt GJ. Paraneoplastic Pemphigus. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings. 2004;9:29–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fellner MJ, Sapadin AN. Current therapy of pemphigus vulgaris. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68(4–5):268–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toth GG, Jonkman MF. Therapy of pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(6):761–767. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. Results obtained in 84 patients between 1961 and 1982. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(1):44–47. doi: 10.1001/archderm.120.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]