Abstract

Background:

Despite considerable investment in research, the existing research evidence is frequently not implemented and/or leads to useless or detrimental care in healthcare. The knowledge-practice gap proposed as one of the main causes of not achieving the treatment goals in diabetes. Iran also is facing a difference between the production and utilization of the knowledge of diabetes. The aim of this study was to assess the status of diabetes knowledge translation (KT) in Iran.

Methods:

This was a survey that executed in 2015 by concurrent mixed methods approach in a descriptive, cross-sectional method. The research population was 65 diabetes researchers from 14 diabetes research centers throughout Iran. The research was carried out via the self-assessment tool for research institutes (SATORI), a valid and reliable tool. Focus group discussions were used to complete this tool. The data were analyzed using quantitative (descriptive method by Excel software) and qualitative approaches (thematic analysis) based on SATORI-extracted seven themes.

Results:

The mean of scores “the question of research,” “knowledge production,” “knowledge transfer,” “promoting the use of evidence,” and all aspects altogether were 2.48, 2.80, 2.18, 2.06, and 2.39, respectively. The themes “research quality and timeliness” and “promoting and evaluating the use of evidence” received the lowest (1.91) and highest mean scores (2.94), respectively. Except for the theme “interaction with research users” with a relatively mediocre scores (2.63), the other areas had scores below the mean.

Conclusions:

The overall status of diabetes KT in Iran was lower than the ideal situation. There are many challenges that require great interventions at the organizational or macro level. To reinforce diabetes KT in Iran, it should hold a more leading and centralized function in the strategies of the country's diabetes research system.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, knowledge translation, research centers

INTRODUCTION

Billions of dollars worldwide are spent annually on biomedical research,[1,2] but one of the research findings, which have been repeated in many researches on clinical services and health in the world, is the failure in the transfer of research into practice. As a result of this evidence-practice gap, patients have failed to properly take advantage of advances in health care.[1,2,3] Therefore, there is a need to eliminate the gap between the diagnosis and evidence-based ideal practices and treatments by professional specialists in the real world; this need has led to the emergence of a new field of research that is known as the knowledge translation (KT) research. One of the main issues addressed by this type of research is the identification of barriers hinder physicians to use evidence-based options and the methods to overcome these barriers.[4]

KT is a concept which is developing along with an unprecedented global investment in health research; hence, it has generated a large volume of knowledge which has had low levels of application. The generated knowledge has not been adequately and properly put in action as and has not led to the formulation of new or progressive policies, products, and services.[5]

The gap between the new knowledge and its application is also clear in chronic diseases, especially in diabetes.[6]

Global epidemic of diabetes is a major challenge which is faced by health care service providers.[7] Without a doubt, control of diabetes is a public health issue of high priority in the 21st century.[8] Various reasons are proposed as the main causes of not achieving the treatment goals in diabetes including lack of adherence to knowledge products-based treatments.[6] Previous studies have revealed a significant gap between the quality of care for common conditions in diabetes and related evidence-based knowledge products.[9] These studies which have been conducted in a variety of environments indicate that diabetes care in the real world often does not adhere to the standards of evidence-based practice.[10] In fact, although new evidence provide effective interpositions to hinder or put over diabetes in risk groups, translating these interpositions into clinical act is the main challenge to be faced in the next steps.[8] Therefore, the majority of researchers believe and argued that research-based diabetes has the potential to reduce variability in the performance and increase effectiveness and efficiency of care services for diabetic patients.[11,12] Indeed, it denotes that there is a need for a better understanding the methods used to implement and maintain evidence-based diabetes care in the real world.[10]

Specific obstacles to evidence-based diabetes challenge should be identified and addressed in the field of KT research. Diabetes KT research is a subject area that its outcomes and results can help prevent further deaths and complications. However, despite the substantial lessons learned about the methods of promoting diabetes KT, documentations related to care seem to be suboptimal.[10]

In Iran, national studies have approximated a considerable level for the spread of diabetes in the country (7.7% in 2005 and 7.8% in 2007). On the other hand, more than 45% of cases the disease is not diagnosed.[13] Another study has reported that the prevalence of diabetes is about 5–8%, with an annual increase of 5000 patients/year.[14] However, the more important point is that Iran also is facing a difference between the production and utilization of the knowledge of diabetes.[6]

In Iran, a decade of work in the field of evidence-based practices, along with other results, has shown the need for the use and transfer of health knowledge. In addition, it highlights the need to use the knowledge products tailored for the needs of users and to provide evidence-based health system.[15] Although, in recent decades, the importance of research in the health system in Iran has been highlighted and increased, we cannot explicitly accommodate the research activities with the necessities of the health sector.[16] Iranian research centers and universities were looking for the different ways to improve their KT activities; although pursuant to the previous studies, these proceedings were not organized or integrated.[17] Previous studies have shown that in addition to factors including relationships between researchers and policy makers, stewardship is the most incisive factor in KT.[18] Other studies show that further to individual factors, organizational factors also influence on KT activities in research centers.[19,20,21] The current study was designed to assess the status of diabetes KT in Iranian diabetes research centers to find out the strengths and weaknesses of principal institutes undertake producing and disseminating diabetes knowledge in Iran as a developing country. This could help diabetes research decision and policy makers to specify the types of action to be taken at each level of the diabetes research system.

METHODS

Settings and design

This was a survey that executed in 2015 by concurrent mixed methods approach in a descriptive, cross-sectional method. The research population in this study consisted of 65 researchers in the field of diabetes studies who were working in 14 diabetes research centers/institutes throughout Iran. The participants were selected via the census.

Data measures

The research was carried out via a tool provided by the KT committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) entitled as the self-assessment tool for research institutes (SATORI). Minor changes were made in this tool. This tool was developed for the self-assessment of KT from the perspective of research institutes,[22] and previously, it has been used for the evaluation of the status of KT in some studies.[19,20,21] Despite the confirmation of the validity and reliability of the tool in previous studies,[19,20,21,22] in this study, face and content validity were again confirmed by 10 experts of KT and diabetes; moreover, its reliability was verified via internal consistency check and the alpha was calculated to be 0.92. The SATORI uses a Likert scale from 1 to 5 for making comparisons, where 1 represents the lowest level of attention and 5 shows the greatest level of attention given to each item mentioned in the tool. The tool consisted of 50 items in four KT domains: “The question of research” (12 items), “knowledge production” (9 items), “knowledge transfer” (25 items), and “promoting the use of evidence” (4 items). Every item of this tool evaluated at least one of the aspects affecting KT.

Data collection

To complete this self-assessment tool, we used focus group discussions (FGDs) and consensus which was carried out by 65 of 75 researchers at the diabetes research centers/institutes. No special sampling method was used, and the participants were included via the census. Two FGDs were held in each of the 10 centers/institutes, and 4 centers/institutes held one FGD. Sessions were directed by research team members, or by a facilitator that nominated on behalf of centers/institutes already. All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed word by word. Data collection was conducted in 2015.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using quantitative and qualitative approaches. Based on SATORI-extracted seven themes in previously conducted studies[19,20,21,22] and by thematic analysis method, the results was analyzed qualitatively. For quantitative analysis, after the initial combination of items collected in the FGDs, using a subset of the items, the mean and standard deviation of each theme were calculated in descriptive statistical methods by Excel 2013 software for all diabetes research centers/institutes. In fact, the quantitative data were the complement of the qualitative findings.

RESULTS

The results of the study are presented in two qualitative and quantitative sections, which are complementary for each other. FGDs participants were also asked to provide information/comments relevant to both qualitative and quantitative parts of the study. It is notable that out of 65 participants in the current survey, 100% was affiliated to research institutes/centers. Sixty percent of them were male, 95.38% were full-time faculty members, and 50.76% were aged 40–50. Moreover, 84.61% of participants had the experience of membership in research councils of the hospitals, schools, and universities.

Qualitative section

Priority setting

We found that in many cases, research priorities had been set by Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME). In recent years and after the establishment of the “Iranian National Diabetes Research Network (INDIRAN)” in some cases, the diabetes research priorities had been determined and declared by this network. However, in a few number of cases, some of the priorities are set through meetings with stakeholders, including nongovernmental organizations. Hence, it can be found that many of these research centers/institutes have no accurately defined mechanism for determining research priorities. As a result, participants believed that the priority setting process is not clear and defined, and the researches are often conducted without considering the needs of users and without their active participation.

“It rarely happens that someone asks us about our true research priorities.”

“Priorities determined by the Diabetes Research Network usually not operational.”

“I do not remember any meeting held with stakeholders to ask for their participation in determining research priorities.”

Research quality and timeliness

Most diabetes researchers believe that their research has an acceptable quality, and the users can trust the findings of the researches conducted in the research centers/institutes. However, their opinions about assurance and quality control of research were various and different. Most of them believed that the situation of these two factors depends on the amount and source of funding.

“The fact that many bodies outside the research center give us orders for conducting researches for them indicates that the quality of our research is good, and they have confidence in our work.”

There were different points of view about the timeliness of research because the reported time to review the proposals varied depending on the type of research and its budget. In addition, the time spent to present the results of the research was different due to these two factors, and sometimes due to the educational level of students who were carrying out the research projects (master, general practitioner, and PhD). However, in some cases, the timeliness of the research was one of the strengths pointed out by the participants.

“I and my other colleagues believe that the speed of accepting the proposals is satisfactory. Of course, we also observe the time specified for the research and the authorities of the research centers and organizations who ordered the researches are satisfied with this aspect.”

Majority of the participants believed that there is a long time interval between the completions of a study and publish research results in scientific journals. From the perspective of researchers, this long time gap led to the loss of value of information and research results; consequently, it reduces their value and capacity for designing and implementing KT interventions.

“It happens frequently that we do a research in 6 months, but sometimes it takes 2 years from the moment of submission to the publication which wastes the time.”

Researchers’ knowledge translation capacities

The researchers were not aware of KT techniques and had no skills required in this area. The majority of researchers working only wanted to publish their papers in the journals, presented their findings at seminars and conferences, and eventually transferred their knowledge to students and their colleagues. Furthermore, there was no comprehensive list of the users of the researches while it is one of the requirements for promoting KT. In addition, most researchers were not equipped with communication skills or could not benefit from these skills. Nevertheless, communication skills are among the major requirements of KT.

“Capacity building for KT does not receive much attention in our research center as it should be. There are some suggestions which are not much applicable in practice.”

“While there is a vivid need to report research results to all stakeholders, there is no particular training in this area.”

Interaction with research users

Poor interaction between researchers and the users of research findings was reported as one of the weaknesses of KT in many diabetes research institutes/centers.

“Not only my fellow colleagues, but also officials and authorizes in the research centers are reluctant to have a free flow of scientific information generated in the diabetes research centers; and sometimes they even do not believe this issue.”

One of the most important tools to interact with users of researches is a comprehensive and applied database of organizations that potentially may take advantage of the findings obtained by diabetes research centers/institutes; however, considering the views of the participants, such a list was often not available. However, considering the research collaboration networks, INDIRAN almost was able to bring together the people working in different areas of diabetes. In addition, the researchers who participated in our study highlighted the good interaction performance of the “Iranian Databank of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders” which was founded by the INDIRAN.

“We do not have a proper knowledge about the population that is using the results of diabetes researches.”

“The establishment of the Diabetes Research Network was an important step for facilitating the communication between researchers in the first place and between researchers and users of research results in the second place.”

In addition, the researchers very rarely involved stakeholders in research projects. Active participation in activities, such as communicating with the media and meetings with decision-makers to transfer research results to its users, was done very rarely.

“The interaction between diabetes researchers and communication channels, including National Broadcasting is not good. However, I think the broadcasting the results of studies of diabetes researches for the people at National Broadcasting in not less valuable than the publication in specialized journals.”

The facilities and prerequisites of knowledge translation

According to the views of the researchers, inadequate budget was one of the main reasons for the lack of activity in the field of KT. However, although some diabetes research centers/institutes did not have any problem in terms of total research budget, a majority of them did not allocate any part of the budget to KT-related activities which should be a part of the project. MoHME did not spend much budget on KT processes.

“No special budget is allocated specifically for the transfer of research results; even in case of allocating a budget, its distribution is not managed well.”

“It is attractive that although the Ministry of Health suggests the topics for the research and, in fact, determines the priorities by its own, but it does not make it clear whether there is any budget to transfer the results or not. Indeed, the answer is no.”

There was not any individual or structure in diabetes research centers/institutes with a defined job description to work as a knowledge broker. Furthermore, researchers were not able to benefit from the skills of professionals who were familiar with KT skills. Only in a research center, a series of KT workshops was held for scholars and researchers working in the center.

“There is no qualified person or body involved in the KT processes in the process of doing research to cooperate with researchers and provide support or guidance for them to facilitate the transfer of research results.”

Another barrier to KT that researchers noted was the lack of enough time to spent on KT processes. More than half of them pointed out that they had not enough time to prepare the content required for KT.

“Teaching, research, and sometimes administrative responsibilities do not leave much time for us to spend on KT activities.”

Processes and regulations supporting knowledge translation

It is obvious that carrying out customer-oriented researches, as a means to facilitate KT, needs some regulations. This is defined in about half of the diabetes research centers/institutes, yet most of the researchers were not aware of it.

“There are many officials and authorities who constantly speak about the importance of the transfer of research results, but the question is whether they have prepared any regulation to support the process? Maybe there are some laws and regulation but we are not aware of them.”

“I recently learned quite by chance that there is a set of rules for facilitating this process (KT).”

In most cases, obtaining financial support from outside the research center is not desirable; the main reason is the administrative barriers on both sides. Taking help from the sector outside the organizations is a very time-consuming and tedious process so that the researchers usually are not willing to use this option.

“With reference to funding provided by the entities outside the research centers, they have so many bureaucratic challenges for the researchers that at the end the researchers prefer to give up.”

The lack of specific mechanisms or flowchart to transfer the results of a project is one of the main obstacles to carrying out such activities in diabetes research centers/institutes. In fact, there is no determined process for specifying which research findings and in what method should be transferred to the target audiences.

“I still do not know which flowchart should be used as the framework to carry out a KT process in the institute; above all, I think there is no such a thing at all.”

Only a few researchers believed that there were laws to protect intellectual property rights.

“Recently, some fairly good laws have been passed and approved to protect intellectual property rights.”

In the studied diabetes research centers/institutes, there was no law or regulation for evaluating KT activities conducted by researchers.

“When there is no certain rule to assess the activities related to the transfer of research results, it is usual that the researcher has no incentive to involve in these activities.”

Promoting and evaluating the use of evidence

Only in a few cases in diabetes research centers/institutes, the educational programs on evidence-based decision making were provided on a fairly regular basis for some groups of researchers and decision-makers. In most research centers, the capacity building programs for utilizing evidence were held only for target audiences inside the research center/institute, and they had no program for the external target audiences.

“In case of holding any program for KT capacity building, it is mainly for users inside the research institute not for those outside the institute.”

It seems that because of some neglects by decision-makers in the clinical field, many researchers do not pay much attention to the use of the results of a project and the effectiveness of the results in the decision-making process.

“No matter whether we present our results to decision-makers or not, they do not use them in their decisions. So it is natural that this is not important for us as well.”

One of the major reasons for researchers’ reluctance to submit the results of their research to decision-makers is the lack of a monitoring and evaluation system to assess the outcomes of the use of research evidence and the resulting changes in the behaviors. This in turn is due to the fact that assessing the behavioral changes in decision-makers is a time-consuming process, and above all, the managerial status of decision-makers is rapidly changing.

“When we want to see the outcomes of the utilization of research results and to know which problems are solved, soon we will be informed that the decision-maker is changed and is replaced by someone else.”

Aside from the fact that many diabetes research centers/institutes did not allocate specific funding for the development of knowledge products, (such as systematic reviews and clinical guidelines); more importantly, even if they were to develop, there is no guarantee to ensure that health service providers take advantage of the products; moreover, there is no tool and method for evaluating them.

“Although a lot of time and cost is spent on developing clinical guidelines for diabetes, unfortunately, there is not a satisfactory level of utilization in practice. Even when they are used, there is no way to measure the outcomes.”

Quantitative section

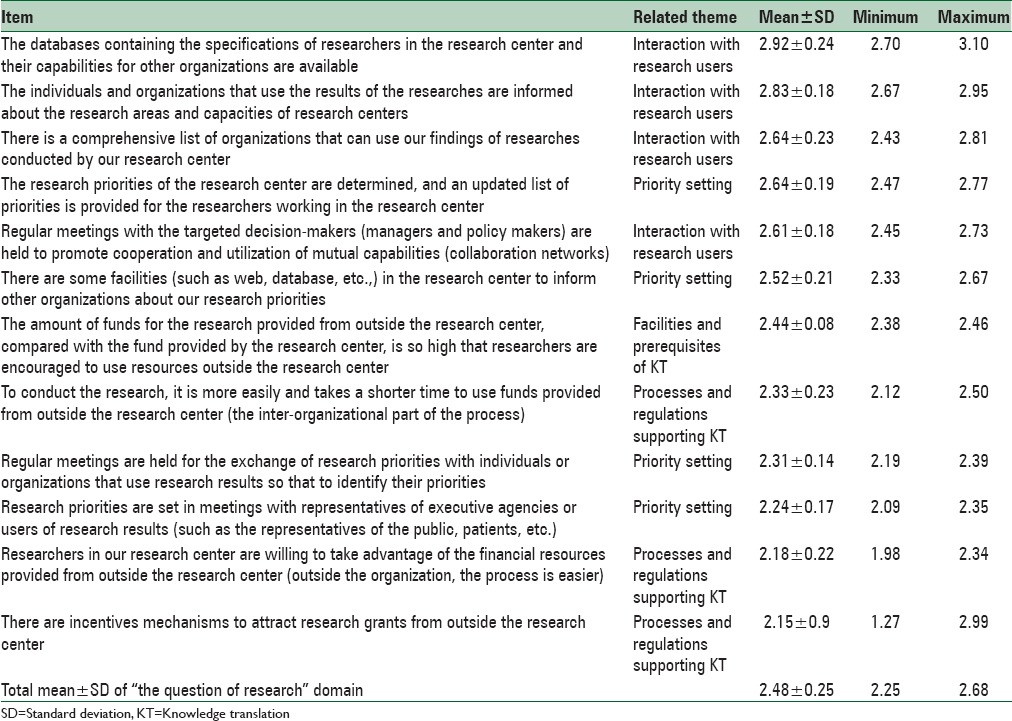

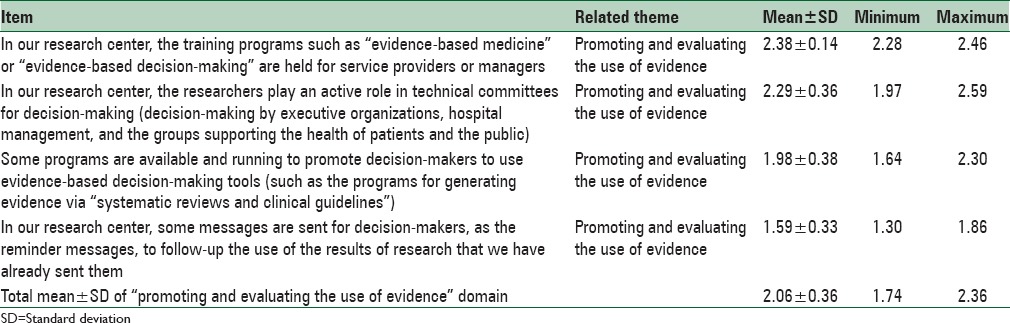

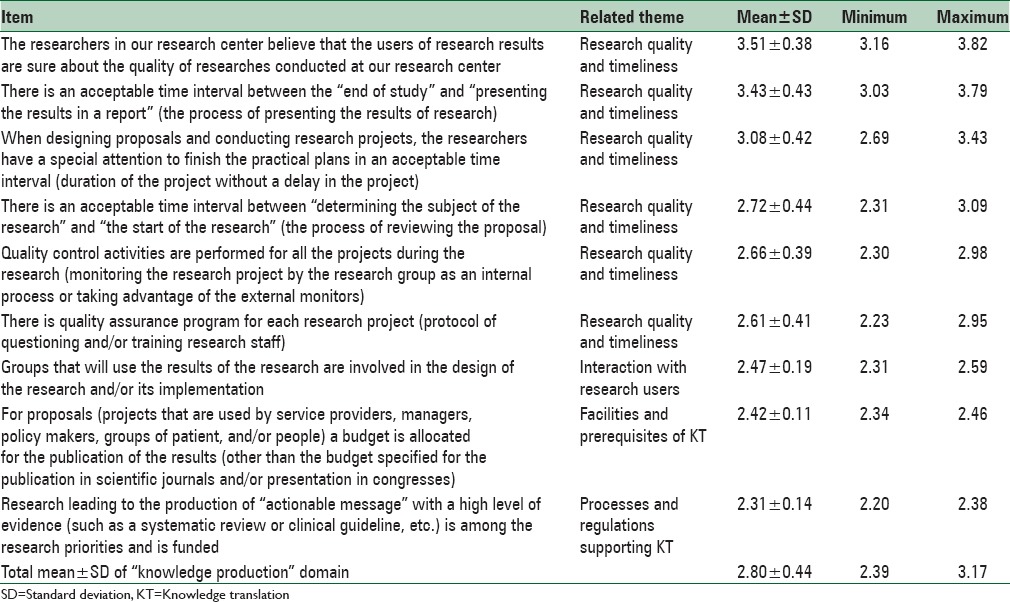

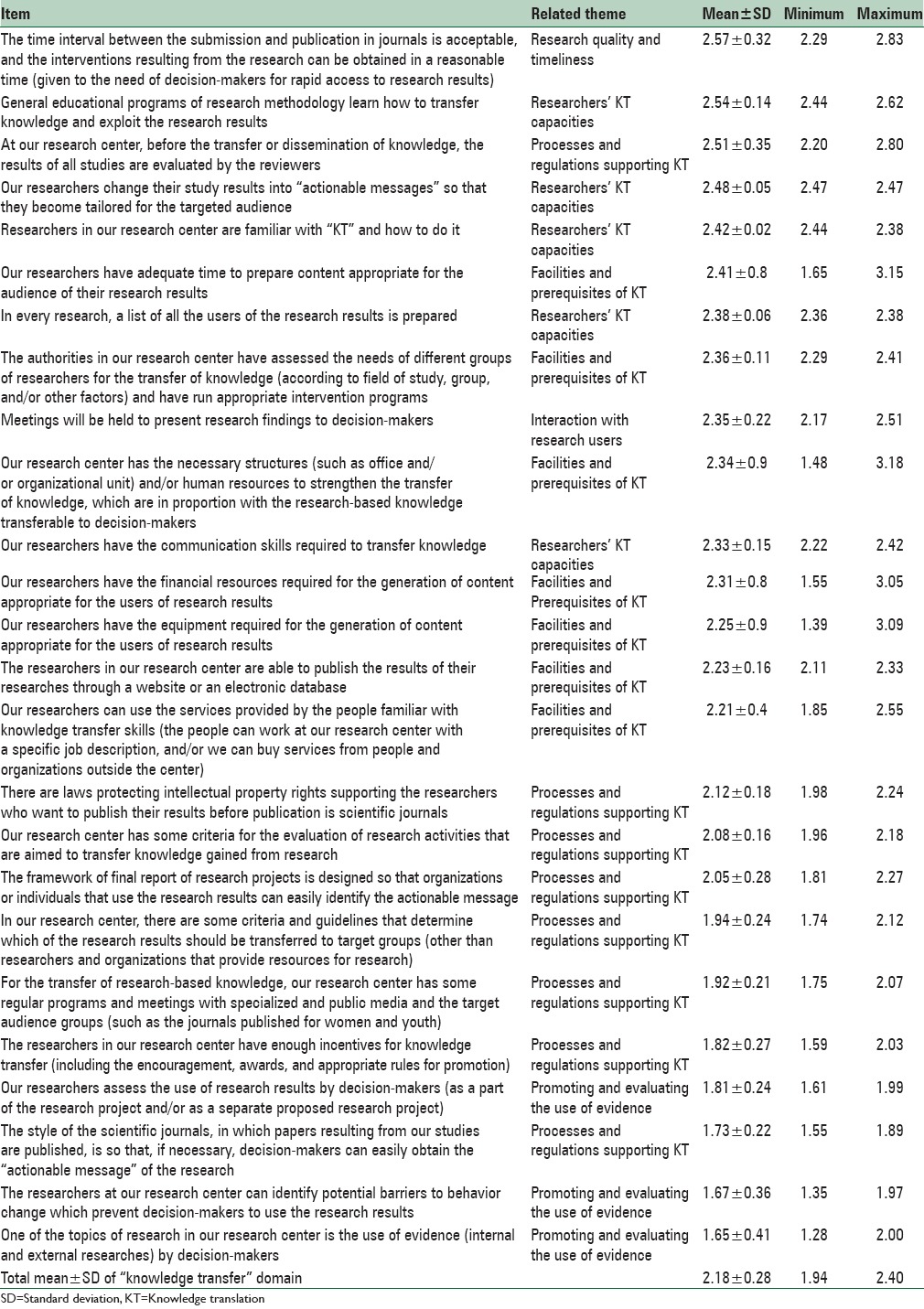

The quantitative status of KT activities is shown in Tables 1–4. The mean score and standard deviation of each item of SATORI for all diabetes research centers/institutes are presented in the tables. The means score of “the question of research,” “knowledge production,” “knowledge transfer,” and “promoting the use of evidence” were 2.48, 2.80, 2.18, and 2.06, respectively. This means that among all the aspects of KT, only “knowledge production” had a relatively good status, and the rest had an undesirable status. Finally, the mean score of all the aspects altogether was 2.39.

Table 1.

The mean score and SD for each item in “question of research” domain

Table 4.

The mean score and SD for each item in “promoting the use of evidence” domain

First part (the question of research)

Is the diabetes research center/institute able to identify the needs of decision-makers who use the results of the researches [Table 1]?

Second part (knowledge production)

Does diabetes research center/institute produce evidence that are usable in its decision-making [Table 2]?

Table 2.

The mean score and SD for each item in “knowledge production” domain

Third part (knowledge transfer)

Are there any appropriate mechanisms for presenting the results of the researches conducted in the diabetes research center/institute to the targeted audiences [Table 3]?

Table 3.

The mean score and SD for each item in “knowledge transfer” domain

Fourth part (promoting and evaluating the use of evidence)

Does the diabetes research center/institute provide a condition for decision-makers to use research results better [Table 4]?

As it was observed, in each of the four tables, from top to bottom, the level of attention paid by the research center/institute decreased, respectively.

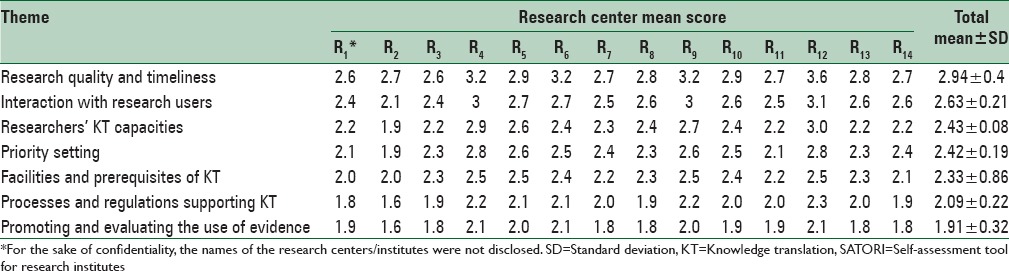

For more quantitative analysis, seven themes listed in the qualitative part were used. For each diabetes research center/institute, the mean scores for each theme were estimated based on the scores obtained for its items. Ultimately, the mean score and standard deviation of the participating centers were presented in seven areas [Table 5].

Table 5.

Mean scores of the Iran's diabetes research centers according to themes of the SATORI

Based on the mean score of all diabetes research institutes/centers, the theme “research quality and timeliness” received the highest score (2.94) while the theme “promoting and evaluating the use of evidence” received the lowest score (1.91). Among the other areas, except for the theme “interaction with research users” that received a relatively mediocre score (2.63), the other areas, with a relatively more or less equal power, had not an ideal status.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study showed that despite an increase in the number of acceptable researches and in scientific publications in recent years in Iran;[23,24,25,26] however, the application of this knowledge at diabetes, as one of the most important subspecialty fields of medicine, is not desirable in Iran. These findings are consistent with previous findings of similar studies conducted in TUMS as the largest medical university in Iran,[19] in Eastern Mediterranean countries that Iran is also part of them,[20] and in the field of Iranian nursing.[21]

The findings of this study can be divided into three categories:First category: Areas in need of too much attention, including “promoting and evaluating the use of evidence” and “processes and regulations supporting KT” areas; second category: Areas needing much attention including “facilities and prerequisites of KT,” “priority setting,” and “researchers’ KT capacities” areas; and finally, the third category: Areas in need of average attention including “interaction with research users” and “research quality and timeliness” areas. Unfavorable status of KT in diabetes research centers/institutes in Iran seems due to the weaknesses, mainly in the areas of the first and second categories. Given that other studies[19,20,21] have attained fairly similar results; therefore, the above-mentioned areas are in need of effective interventions.

In the area of “promoting and evaluating the use of evidence,” since the transfer activities are not carried out well, and therefore, there has been no promotion or evaluation of evidence, the low score received by this domain should not be surprising. On the other hand, in “processes and regulations supporting KT,” it seems that the design of some regulations can encourage researchers to increase their KT activities. In pioneer countries, there are some regulations to include KT activities in standards designed for the promotion, intellectual property rights, and awarded prizes for KT.[20]

The score obtained for “facilities and prerequisites of KT” theme show that this area needs to receive more attention from management system and interventions at the national level.

The low score of “priority setting” suggests that despite efforts to improve the priority setting,[20] it seems that the priority setting activities do not receive much attention in low- and middle-income countries. Other studies executed in the region also endorses our results.[27,28] Because the budget assigned to research is usually downward in these countries, it is even more important to do diabetes research as well as on the national and local preferences. One of the reasons for the deficiency of research on health preferences may be because of the gap between evidence producer centers (especially universities) and decision-makers in the health sector.[21] It is believed that the holding meetings periodically for priority setting can help healthcare organizations to overcome these shortcomings.[19] It is an obstacle that has been overcome with the creation of knowledge networks.[21] This probably was one of the reasons for the establishment of INDIRAN. This network was established by diabetes research center at TUMS; it acts as an integrated and systematic national framework to encourage research on various aspects of diabetes.[29] Although one of the objectives and functions of INDIRAN was to set the research priorities of diabetes in Iran, according to the results of this study, it seems that the network has not been successful in achieving this goal.

The low score of “researchers’ KT capacities” suggests that this area needs further efforts including KT capacity building in diabetes research. Educational programs can be effective for this purpose. In addition, diabetes researchers as well as decision-makers can be empowered through using the services of knowledge brokers.[21,30,31]

The status of “interaction with research users” was relatively good in the studied diabetes research centers/institutes. In this respect, the results were not in line with the results of studies by other studies.[19,20,21,28] The difference may be attributed to the presence of INDIRAN. It seems INDIRAN has almost brought together the people from different areas and fields of diabetes research, leading to greater interaction between them. One of the goals of the network is to identify research teams working in the field of diabetes in Iran and to initiate the interaction between them.[29]

Previous studies have shown that only a small number of researchers use active techniques to disseminate the results of their research.[19,20,21,32,33] This was also one of the results of this study and it suggested that systematic efforts are needed to stimulate researchers to deliver their messages to users and create a suitable environment for KT activities.

Apparently, there is no problem with regard to “research quality and timeliness” in diabetes. Almost all of participants gave a relatively good score to this area. In this respect, the findings of this study were consistent with other studies.[19,20,21] Of course, part of the score obtained for this area may be due to researchers’ bias for rating their activities. However, evidence suggests a growing trend of research and research products all over the country; hence, it seems that this area is not in need of an urgent intervention.

To strengthen the KT activities of researchers, Jacobson et al. have proposed to conduct interventions at the organizational level in the following areas: Recruitment and promotion rules, budget and resource allocation, improvements in the structures, shifting the focus to the policies of KT, firm commitment to KT, training KT skills to students, recruiting researchers with the required skills, documentation, standardization and promotion of KT activities, and planning and promoting the use of evidence.[34] The establishment of research networks is another attempt to bring together researchers and potential users and increase their interaction.[20] In this regard, as previously mentioned, one of the most important activities in the field of diabetes research in Iran was the establishment of INDIRAN. The network has several objectives and functions in order to improve diabetes KT, including improving the quality and the quantity of diabetes research, running workshops and training sessions for diabetes research teams, the development of standard Iranian Diabetes Guidelines, and developing a software to support and facilitate clinical decision making on diabetes (Hakim software).[29] Although according to the findings of this study, it seems at least in the dimensions related to KT, this network has not been successful as it should.

Obviously, there are some failures and shortcomings in the use of research evidence for informed decision-making in health care by all the key decision-making groups in developed and developing countries as well as in primary care and specialized care.[3,35] Therefore, KT strategies may be different for different target user audiences, and the type of knowledge transfer can also vary; hence, there is a need for a better understanding of different decision-makers and their needs.[3] In the case of diabetes, although there are some algorithms for diabetes care, they may be difficult to be followed by physicians because there are certain challenging issues such as diabetes KT challenges. As a result, the health care system often fails to reach the predefined global quality standards of diabetes management.[7]

CONCLUSIONS

There were many deficiencies in various portions of diabetes KT in Iran. The reality that there are deficiencies in approximately whole of surveyed areas leads to conclude that planning for and supporting KT does not happen at the organizational or so-called macro level in the diabetes research system primarily. However, in spite the efforts being made in some areas to improve the status, there are many challenges that require great interventions at the organizational or macro level. Accordingly, the subject should be observing in stewardship and policymaking at the organizational or macro level, followed by sketching and implementation at the research centers level. In spite the diversity in the contexts, there are many likenesses in the diabetes research institutes/centers included in this study. In order to reinforce diabetes KT in Iran, it should hold a more leading and centralized function in the strategies of the country's diabetes research system.

Ethical consideration

To observe the ethical dimension of research, at the beginning of the meetings, the aim of the study was explained. Interviews were recorded after obtaining the free and informed consent of the interviewees. During data analysis, the name of the participants and their organizational affiliations were excluded. The study was approved by (Medical Ethic No: IR.IUMS.REC.1394.9211563206) the Research Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was part of a PhD thesis supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS/SHMIS_1392/D/431/703). The authors would like to thank all of the participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straus SE, Tetroe JM, Graham ID. Knowledge translation is the use of knowledge in health care decision making. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S. Knowledge translation and interprofessional collaboration: Where the rubber of evidence-based care hits the road of teamwork. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:46–54. doi: 10.1002/chp.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landry R, Amara N, Pablos-Mendes A, Shademani R, Gold I. The knowledge-value chain: A conceptual framework for knowledge translation in health. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:597–602. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.031724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. Which information resources are used by general practitioners for updating knowledge regarding diabetes? Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:223–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Belvis AG, Pelone F, Biasco A, Ricciardi W, Volpe M. Can primary care professionals’ adherence to evidence based medicine tools improve quality of care in type 2 diabetes mellitus? A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;85:119–31. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narayan KM, Benjamin E, Gregg EW, Norris SL, Engelgau MM. Diabetes translation research: Where are we and where do we want to be? Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:958–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goderis G, Borgermans L, Mathieu C, Van Den Broeke C, Hannes K, Heyrman J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to evidence based care of type 2 diabetes patients: Experiences of general practitioners participating to a quality improvement program. Implement Sci. 2009;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfield SA, Malozowski S, Chin MH, Narayan KM, Glasgow RE, Green LW, et al. Considerations for diabetes translational research in real-world settings. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2670–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu-Qamar M, Wilson A. Evidence-based decision-making: The case for diabetes care. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2007;5:254–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2007.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasan H, Zodpey S, Saraf A. Diabetologist's perspective on practice of evidence based diabetes management in India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;95:189–93. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarayani A, Rashidian A, Gholami K. Low utilisation of diabetes medicines in Iran, despite their affordability (2000-2012): A time-series and benchmarking study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005859. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varaei S, Salsali M, Cheraghi MA, Tehrani MR, Heshmat R. Education and implementing evidence-based nursing practice for diabetic patients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013;18:251–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baradaran-Seyed Z, Majdzadeh R. Evidence-based health care, past deeds at a glance, challenges and the future prospects in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majdzadeh-Kohbanani SR. Montreal: Universite de Montreal; 2011. Barriers of evidence based policy making in Iran's health system. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Majdzadeh R, Nedjat S, Fotouhi A, Malekafzali H. Iran's approach to knowledge translation. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majdzadeh R, Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Gholami J, Ahghari S. Strengthening evidence-based decision-making: Is it possible without improving health system stewardship? Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:499–504. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Roshan SM, Dizaji SL, Maddah SS. Organizational activities in nursing research transfer from viewpoint of nurse educators in Iranian universities of medical sciences. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2012;1:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gholami J, Ahghari S, Motevalian A, Yousefinejad V, Moradi G, Keshtkar A, et al. Knowledge translation in Iranian universities: Need for serious interventions. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:43. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maleki K, Hamadeh RR, Gholami J, Mandil A, Hamid S, Butt ZA, et al. The knowledge translation status in selected Eastern-Mediterranean universities and research institutes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gholami J, Majdzadeh R, Nedjat S, Nedjat S, Maleki K, Ashoorkhani M, et al. How should we assess knowledge translation in research organizations; designing a knowledge translation self-assessment tool for research institutes (SATORI) Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falahat K, Eftekhari M, Habibi E, Djalalinia Sh, Peykari N, Owlia P, et al. Trend of knowledge production of research centers in the field of medical sciences in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(Suppl 1):55–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sepanlou SG, Malekzadeh R. Health research system in Iran: An overview. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:392–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peykari N, Owlia P, Malekafzali H, Ghanei M, Babamahmoodi A, Djalalinia S. Needs assessment in health research projects: A new approach to project management in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:158–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peykari N, Djalalinia S, Owlia P, Habibi E, Falahat K, Ghanei M, et al. Health research system evaluation in I.R. of Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:394–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy A, Khoja TA, Abou-Zeid AH, Ghannem H, IJsselmuiden C. WHO-EMRO/COHRED/GCC NHRS Collaborative Group. National health research system mapping in 10 Eastern Mediterranean countries. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:502–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Jardali F, Lavis JN, Ataya N, Jamal D. Use of health systems and policy research evidence in the health policymaking in eastern Mediterranean countries: Views and practices of researchers. Implement Sci. 2012;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amiri-Moghaddam S, Heshmat R, Larijani B. Iranian National Diabetes Research Network project: Background, mission, and outcomes. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10:83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward V, House A, Hamer S. Knowledge Brokering: The missing link in the evidence to action chain? Evid Policy. 2009;5:267–79. doi: 10.1332/174426409X463811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conklin J, Lusk E, Harris M, Stolee P. Knowledge brokers in a knowledge network: The case of seniors health research transfer network knowledge brokers. Implement Sci. 2013;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R, Gholami J, Nedjat S, Maleki K, Qorbani M, et al. Knowledge transfer in Tehran university of medical sciences: An academic example of a developing country. Implement Sci. 2008;3:39. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, McLeod CB, Abelson J Knowledge Transfer Study Group. How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q. 2003;81:221–48. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Organizational factors that influence university-based researchers engagement in knowledge transfer activities. Sci Commun. 2004;25:246–59. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I. Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ. 2009;181:165–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]