INTRODUCTION

In individuals with cognitive impairment (CI), most clinical and epidemiological studies show that depression (DEP) increases the risk of developing dementia 1. In patients with both depression and cognitive impairment (DEP-CI), the conventional expectation is that successful treatment of depression leads to cognitive improvement. However, elderly patients with DEP-CI often do not show cognitive improvement with antidepressant treatment 2,3, and have a high rate of transitioning to dementia.

In DEP-CI patients treated with antidepressants, we previously reported an improvement in episodic verbal memory with the cholinesterase inhibitor (CheI) donepezil in a 12-week placebo-controlled pilot trial2. Olfactory identification deficits are known to predict the transition from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer's Disease (AD)4. Muscarinic cholinergic transmission plays a major role in odor identification, and there is initial evidence that improvement in odor identification is associated with clinical improvement in patients with AD who receive CheI 5. In this pilot report, we explored the impact of olfactory identification as a seconday predictive measure from the previously published efficacy study on treatment response to donepezil in DEP-CI patients2.

METHODS

Outpatients were recruited from the Late Life Depression Clinic and Memory Disorders Center at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. The study was IRB-approved and conducted in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Written informed consent was obtained prior to study entry.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Patient inclusion criteria were age 55-80 years, subjective cognitive complaints, cognitive impairment ≤ 10 years by history, Folstein Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) score > 20/30, major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder by DSM-IV criteria, and a 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-24) ≥ 14. Neuropsychological inclusion criteria required Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) recall score ≤ 2/3 objects at 5 minutes and/or impaired performance >1 SD below standardized norms on at least two tests or > 1.5 SD below standardized norms on at least one test on a brief neuropsychological test (NPT) battery. The NPT battery comprised the Selective Reminding Test (SRT; targeting memory), WAIS-III digit symbol and Trailmaking B (executive function), CFL-version of the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT-CFL)(verbal fluency), and Trailmaking A (attention/psychomotor speed) 2.

Exclusion criteria were other DSM-IV Axis 1 psychiatric disorders, dementia, unstable acute medical condition, specific neurological disorder (e.g., stroke, Parkinson's disease), and anosmia (University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test , UPSIT ≤ 12/40) 6 . In brief, this study sample comprised patients with depression and cognitive impairment without a clinical diagnosis of dementia.

22. Procedures

Odor identification was assessed using the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), which employs 40 scratch and sniff multiple choice format items with the total score ranging from 0 to 40 7. After neurological and psychiatric examination and routine baseline laboratory tests, the UPSIT was administered at baseline,.

The NPT battery was administered at baseline, 8 weeks, 20 weeks and at study exit if it occurred prior to 20 weeks. The primary outcome measure, selected a priori, was the Selective Reminding Test (SRT) total immediate recall score (SRT-tot). The 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-24) and the Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale (CGI) were used to monitor depression.

Following baseline testing, sertraline was prescribed with an alternative doctor's choice antidepressant for patients previously intolerant/unresponsive to sertraline. Medication dose was titrated in a stepwise fashion over the first four weeks based on efficacy and side effects. The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, add-on donepezil phase was initiated at week-8 for all patients with persistent subjective cognitive complaints or NPT scores > 1 SD below standardized norms on any test at the 8-week time-point. Donepezil or placebo in identical-looking tablets was dispensed at 5 mg/day for the first 4 weeks and was increased to 10 mg for the remainder of the trial, with additional dose-adjustment based on side effects.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Baseline demographic and clinical measures were compared between the donepezil (n=11) and placebo (n=7) groups by using t-test and chisquare for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Intent-to-treat analyses (last observation carried forward) were conducted. The treatment groups (donepezil or placebo) were compared with ANCOVA on SRT-tot scores as the dependent variable. UPSIT scores were analyzed as continuous variables and also dichotomized (median split < 30 versus ≥ 30) for clinically relevant analyses. All analyses were two-tailed with alpha<0.1 for significance because this was a pilot trial with small sample size.

RESULTS

Two patients dropped out prior to entering the double-blind placebo-controlled donepezil trial. Anosmia based on the initial test performance (score < 12) led to exclusion of two additional patients from the data analysis. Therefore, of 22 patients who started the study, 18 patients were included in analyses. No treatment group differences were noted in baseline demographics and UPSIT scores, and measures of depression and cognition at week 8 (Table 1). The mean baseline UPSIT score of 28 was similar to that previously reported in patients with MCI 4. The reported side effects measured by the Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS) was similar in both the donepezil and placebo treated patients. There were no significant correlations between the baseline UPSIT score and baseline or 8-week cognitive test scores (MMSE, SRT-tot, COWAT-CFL , Trailmaking A and B) or depressive symptom scores (HRSD-24).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical features of the sample

| Measure |

Treatment

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil (N=11) Mean (SD) | Placebo (n=7) Mean (SD) | p value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age in years | 66.5 (9.8) | 67.0 (9.00) | >0.9 |

| Education in years | 13.1 (3.8) | 11.7 (6.1) | >0.5 |

| Gender (% Female) | 45 | 86 | >0.1 |

| Clinical | |||

| MMSE (0-30) | 25.7 (2.0) | 25.9 (2.5) | >0.8 |

| 24-item HRSD | 8.5 (6.9) | 8.4 (4.1) | >0.1 |

| Neuropsychological | |||

| Verbal Memory | |||

| SRT-tot | 32.0 (12.2) | 41.8 (15.4) | >0.1 |

| Verbal Fluency | |||

| COWAT-CFL | 32.6 (12.5) | 36.7 (13.6) | >0.5 |

| Attention/Psychomotor | |||

| Trailmaking A | 73.4 (22.9) | 107.1(68.1) | >0.2 |

| Executive | |||

| Trailmaking B | 195.9 (91) | 137.8 (66) | >0.2 |

| WAIS-III digit symbol | 42.3 (17.5) | 35.5 (22.8) | >0.4 |

| Olfaction | |||

| UPSIT (0-40) | 28 (4.7) | 28 (6.9) | >0.8 |

Patients with depression and cognitive impairment (DEP-CI) were randomized to donepezil or placebo. MMSE: Mini Mental State Exam, HRSD-24: 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, SRT- tot: Selective Reminding Test- total recall, COWAT-CFL: CFL-version of the Controlled Oral Word Association Test, WAIS: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, UPSIT: University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test.

ANCOVA with SRT-tot change score (8 to 20 weeks) as the dependent variable showed a main effect of treatment group (donepezil vs. placebo, F1,12 =11.3, p=0.006). SCID diagnosis (major depression or dysthymic disorder) F1,12 =6.5, p=0.02) and baseline UPSIT score (F1,12 =4.6, p=0.05) were significant covariates. In similar analyses restricted to patients with major depression (n=15), the effect of treatment group (F1,10 = 9.4, p=0.01) and baseline UPSIT score (F1,10 = 3.72, p=0.08) remained significant. In Pearson correlation analyses, baseline olfactory performance scores (UPSIT score) inversely correlated with improvement in SRT-tot score (8 to 20 weeks) in the donepezil (r=−0.56; p=0.07) but not the placebo (r=−0.20; p=0.6) group, indicating that worse olfactory performance was associated with better episodic verbal memory performance after 12 weeks on donepezil.

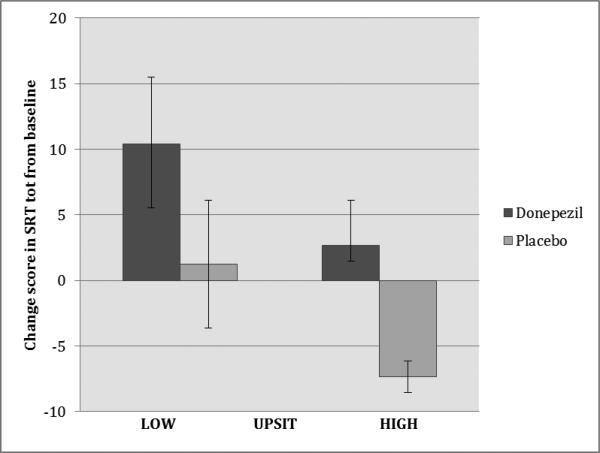

In additional analyses, the sample was dichotomized by the median UPSIT score (low<30 vs. high≥30). In a two-way ANOVA using SRT-tot change score (8 to 20 weeks) as the dependent variable and treatment group (donepezil or placebo) and dichotomized UPSIT scores as between subject variables, both treatment group (F1,14=4.6, p=0.05) and baseline olfactory performance (F1,14=3.4, p=0.09) were associated with the improvement in SRT-tot score. In the donepezil group with low UPSIT scores, there was a mean (SD) increase of 10.4 (11.4) points (44% improvement) in SRT-tot scores after donepezil treatment compared to 2.7 (8.4) points (11% improvement) in those with high UPSIT scores. In patients on placebo, there was a mean increase of 1.25 (9.7) points (8% improvement) in patients with low UPSIT scores and a mean 7.3 (2.1) decrease (16% worsening) in patients with high UPSIT scores (Figure 1). In a post-hoc t-test that compared patients who received donepezil and had low UPSIT scores (n=5) to the rest of the sample (n=13), there was significant improvement in SRT-tot scores in the donepezil group with low UPSIT scores compared to the rest of the sample (t=2.15, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Change in Selective Reminding Test total immediate recall in patients with low and high olfaction (UPSIT) scores.

Mean change in SRT total immediate recall scores over the 8 to 20 week period for patients with low vs. high UPSIT scores (median split < 30 versus ≥ 30) in treatment groups. SRT tot: Selective Reminding Test (12 words, 6 trials) total immediate recall score, range 0-72 with higher scores indicating superior recall. UPSIT: University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, range 0-40, higher scores indicate superior odor identification. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM).

DISCUSSION

The findings indicate that olfactory identification deficits represent a potential biomarker to predict response to cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in patients with DEP-CI. Olfactory deficits are an indicator of underlying Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain pathology, and potentially can be useful to predict improvement with CheI not only in patients with DEP-CI but possibly in patients with MCI and mild AD.

Cholinesterase inhibitors increase muscarinic cholinergic neurotransmission in the brain, and muscarinic cholinergic receptors play a prominent role in the olfactory pathway 5,8,9. Further, intranasal atropine, a muscarinic antagonist, when administered to human subjects is associated with a reduction of odor identification test performance in patients at high risk of developing AD 9. In another study, patients with mild to moderate AD showed an initial improvement in UPSIT scores with donepezil treatment over 12 weeks that was associated with global ratings of improvement over 3 months 8. These lines of evidence support the potential utility of odor identification deficits, which reflect impairment in muscarinic cholinergic neurotransmision, in the prediction of cognitive improvement with CheI treatment.

The main limitation to this study is small sample size. If the finding of olfactory identification deficits predicting CheI response is replicated in larger samples, utilizing this simple, reliable and relatively inexpensive approach 7 may improve the selection of patients to receive CheI clinically and help avoid unnecessary exposure to CheI in patients unlikely to benefit and/or develop side effects. Odor identification tests may also prove useful in clinical trials of other types of agents in MCI and AD, because the presence of olfactory deficits is an indicator of underlying AD brain pathology and the severity of olfactory deficits is related to the severity of cognitive deficits and dementia 10.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Federal Grants MH50513, MH55716, AG17761, the Alzheimer's Association and by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer, Inc. Pfizer, Inc. was not involved in the design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation or writing of this investigator-initiated study. Dr. Devanand has served as a consultant on the scientific advisory boards of Lundbeck and Abbvie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Devanand DP, Sano M, Tang MX, et al. Depressed mood and the incidence of Alzheimer's disease in the elderly living in the community. Archives of general psychiatry. 1996;53:175–182. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020093011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelton GH, Harper OL, Tabert MH, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled donepezil augmentation in antidepressant-treated elderly patients with depression and cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:670–676. doi: 10.1002/gps.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Butters MA, Lopez O, et al. Maintenance treatment of depression in old age: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of the efficacy and safety of donepezil combined with antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68:51–60. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabert MH, Liu X, Doty RL, et al. A 10-item smell identification scale related to risk for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:155–160. doi: 10.1002/ana.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velayudhan L, Pritchard M, Powell JF, Proitsi P, Lovestone S. Smell identification function as a severity and progression marker in Alzheimer's disease. International psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2013;25:1157–1166. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhury ES, Moberg P, Doty RL. Influences of age and sex on a microencapsulated odor memory test. Chem Senses. 2003;28:799–805. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:489–502. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velayudhan L, Lovestone S. Smell identification test as a treatment response marker in patients with Alzheimer disease receiving donepezil. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2009;29:387–390. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181aba5a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schofield PW, Ebrahimi H, Jones AL, Bateman GA, Murray SR. An olfactory ‘stress test’ may detect preclinical Alzheimer's disease. BMC neurology. 2012;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesholam RI, Moberg PJ, Mahr RN, Doty RL. Olfaction in neurodegenerative disease: a meta-analysis of olfactory functioning in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:84–90. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]