Figure 2. Effect of motion direction on numerosity perception.

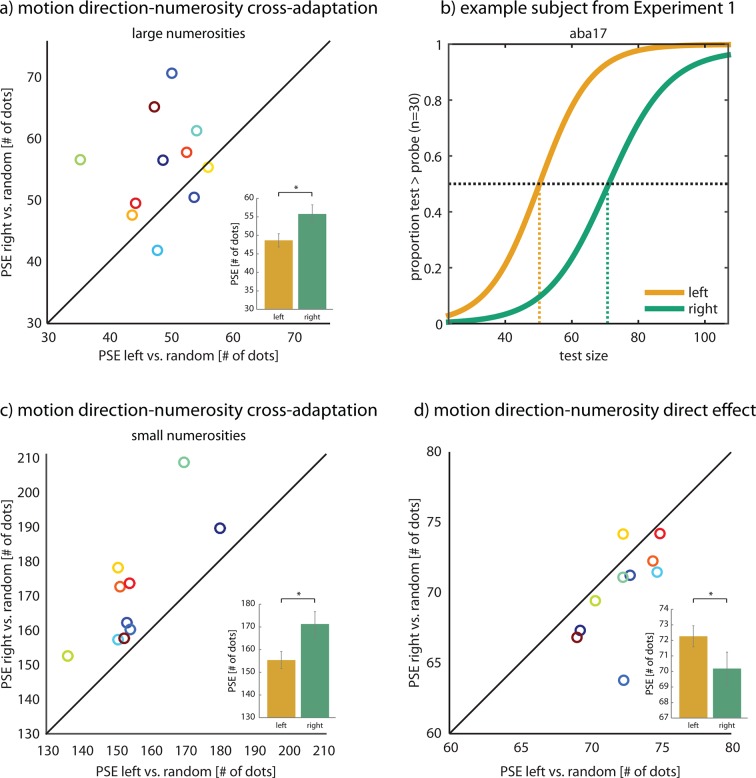

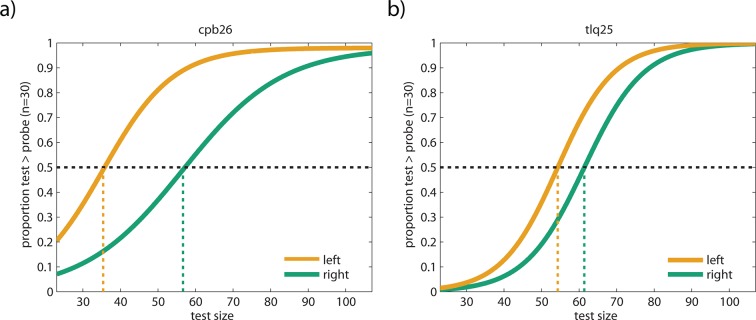

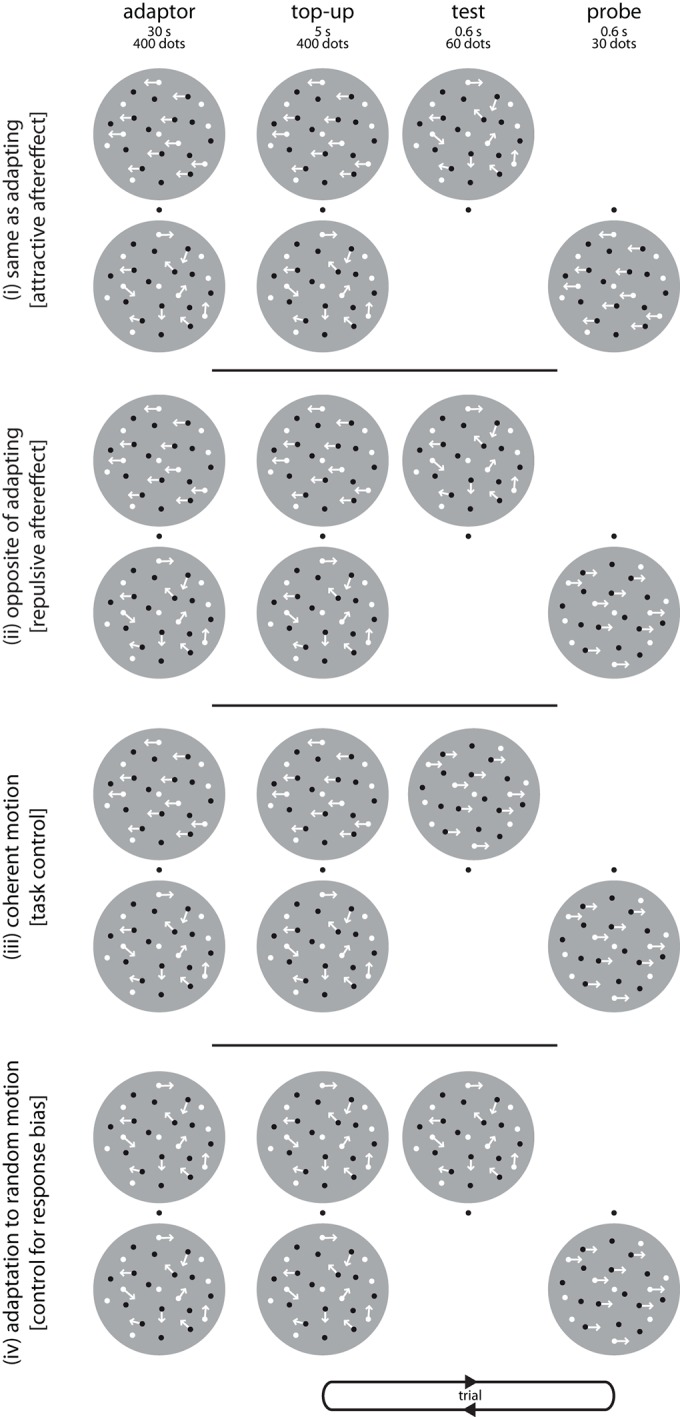

(a) There was a significant repulsive aftereffect of motion direction (left, right) on perceived numerosity (mean difference in PSE 7.12 dots, t(10)=2.555, p=0.029, dHedges=0.953; see inset) when adapting with large numerosities (400 dots) in Experiment 1. The scatter plot pits the PSE after rightward motion against the PSE after leftward motion per subject. It shows that adaptation to rightward motion led subjects to perceive the test cloud as less numerous than adaptation to leftward motion, as evidenced by the large fraction of dots above the equality line, which is indicative of a repulsive aftereffect. This was not due to a classical motion aftereffect (Figure 2—figure supplement 1 and Figure 2—figure supplement 2). (b) Psychometric functions of subject aba17. After adaptation to 400 rightward moving dots in Experiment 1, this subject perceived 70 dots in the test dot cloud to be equivalent to 30 dots in the probe dot cloud, thus underestimating the number of dots in the test. After adaptation to leftwards motion, aba17’s PSE was 20 dots lower than after adaptation to rightwards motion, although the number of dots in the two clouds were identical in both conditions. Note that all psychometric functions are shifted away from 30 dots, the probe size, because of a static numerosity adaptation effect that causes subjects to underestimate consecutively presented dot clouds (Burr and Ross, 2008). See Figure 2—figure supplement 3 for additional example subjects. (c) There was also a repulsive motion direction-numerosity cross-adaptation effect after adaptation to small numerosities (30 dots) in Experiment 2. When adapting with numerosities smaller than the probe (166 dots), subjects overestimate the number of dots in the test cloud (Burr and Ross, 2008). Leftward motion-numerosity cross-adaptation should exaggerate this overestimation effect relative to rightward motion. Indeed, the scatter plot shows that PSEs after leftward motion were consistently smaller than for rightward motion (mean difference 15.85 dots; t(9)=4.523, p=0.001, dHedges=1.017, two-sided). This indicates that, as when adapting with large numerosities, leftward motion shifts numerosity perception down the number line, while rightwards motion shifts numerosity perception up the number line. (d) Motion direction affected numerosity perception also directly, in the absence of adaptation. In Experiment 3, subjects compared the numerosities of coherently and incoherently moving dot clouds without prior adaptation. The scatter plot pits the PSE for rightwards motion against the PSE for leftwards motion per subject, and shows that, indeed, all but one subject perceived clouds of rightward moving dots as more numerous than randomly moving clouds (0% coherence) and clouds of leftward moving dots as less numerous than randomly moving clouds (0% coherence). Accordingly, the PSEs for rightwards vs. leftwards conditions were significantly different (mean difference right vs. left −2.08, t(9)=−2.47, p=0.035, dHedges=−0.707, two-sided). Thus, motion direction affects numerosity estimates also without a preceding adaptation phase. Note that since there is no adaptation, there is also no repulsive aftereffect and hence, the direct effect is of the opposite sign than the repulsive aftereffects in a and c. Data in insets are represented as mean ± SEM. All data shown here are publicly available at Figshare (Schwiedrzik et al., 2015).

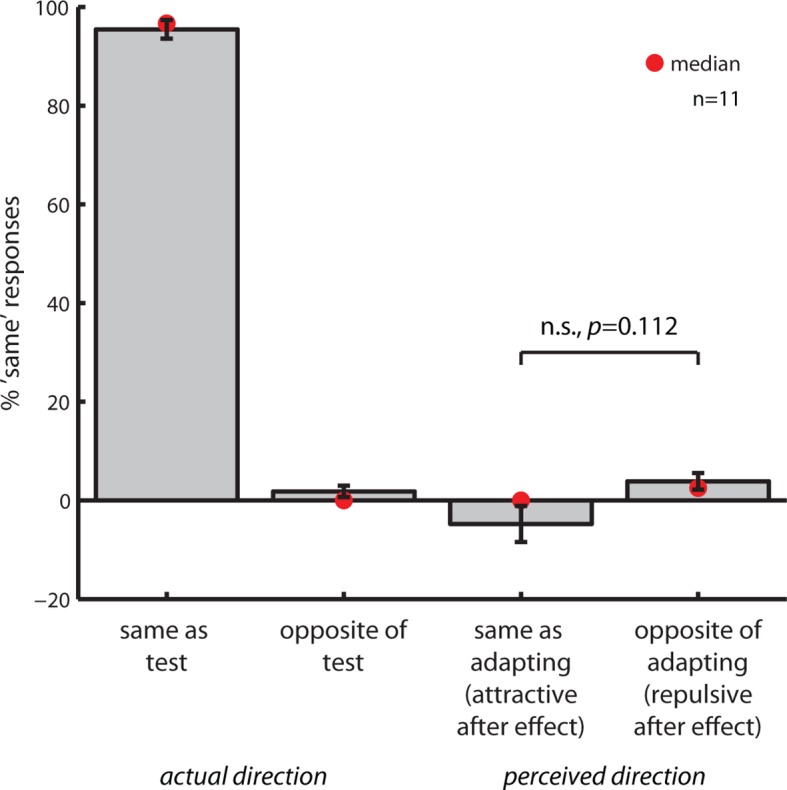

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Adaptation paradigm to test classical motion aftereffects.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Control for classical motion aftereffects.