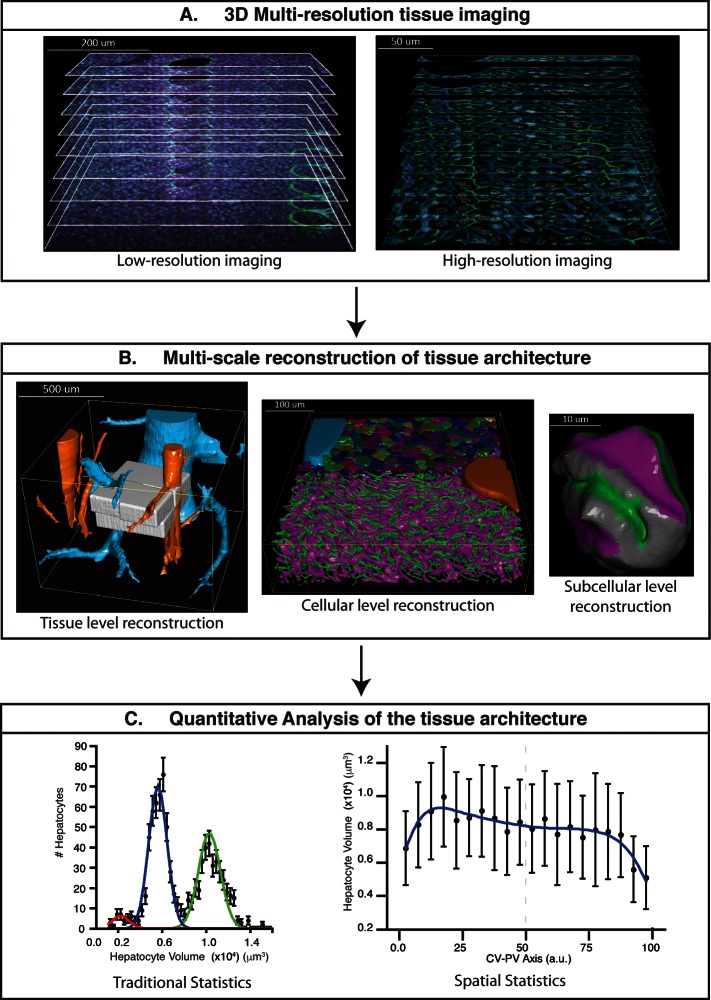

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the proposed pipeline.

(A) 3D multi-resolution image acquisition: example of arrays of 2D images of liver tissue acquired at different resolutions. Low- (1 μm × 1 μm × 1 μm per voxel) and high- (0.3 μm × 0.3 μm × 0.3 μm per voxel) resolution images on the left and right sides, respectively. (B) Multi-scale reconstruction of tissue architecture: on the left, reconstruction of a liver lobule showing tissue-level information, i.e., the localization and relative orientation of key structures such as the portal vein (PV) (orange) and central vein (CV) (light blue). The high-resolution images registered into the low-resolution one are shown in white. On the middle, a cellular-level reconstruction of liver showing the main components forming the tissue, i.e., bile canalicular (BC) network (green), sinusoidal network (magenta) and cells (random colours). The reconstruction corresponds to one of the high-resolution cubes (white) registered on the liver lobule reconstruction (left side). On the right, reconstruction of a single hepatocyte showing subcellular-level information, i.e., apical (green), basal (magenta) and lateral (grey) contacts. (C) Quantitative analysis of the tissue architecture: example of the statistical analysis performed over a morphometric tissue parameter (hepatocyte volume) using the information extracted from the multi-scale reconstruction. On the left, hepatocyte volume distribution over the sample (traditional statistics). On the right, spatial variability (spatial statistics) of the same parameter within the liver lobule. Our workflow allows not only to perform traditional statistical analysis of different morphometric parameters but also to perform spatial characterizations of them. The graphs were generated from the analysis of one high-resolution cube of the multi-scale reconstruction (the one shown in middle of panel B). Boundary cells were excluded from the analysis.

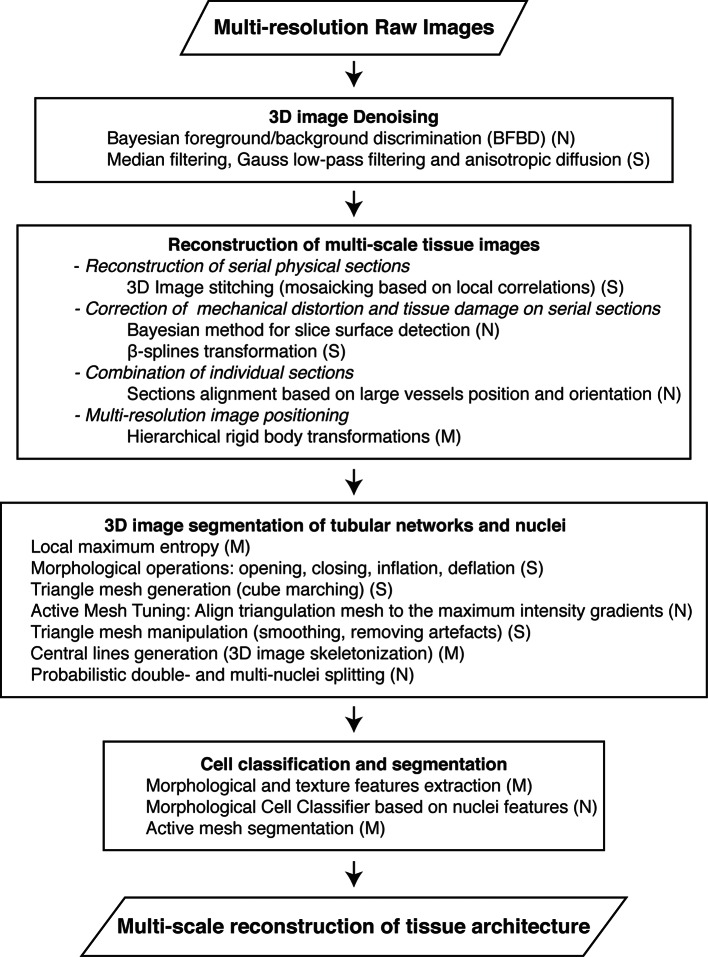

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Workflow for the multi-scale reconstruction of tissue architecture from multi-resolution confocal microscopy images.

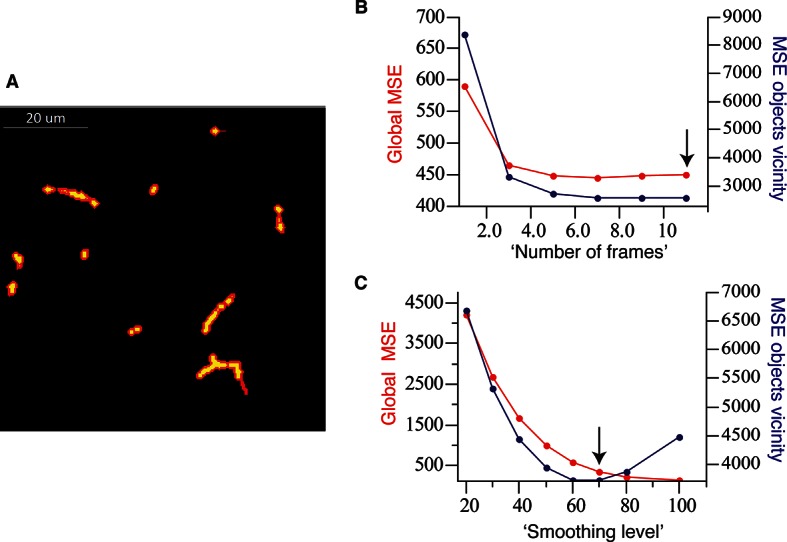

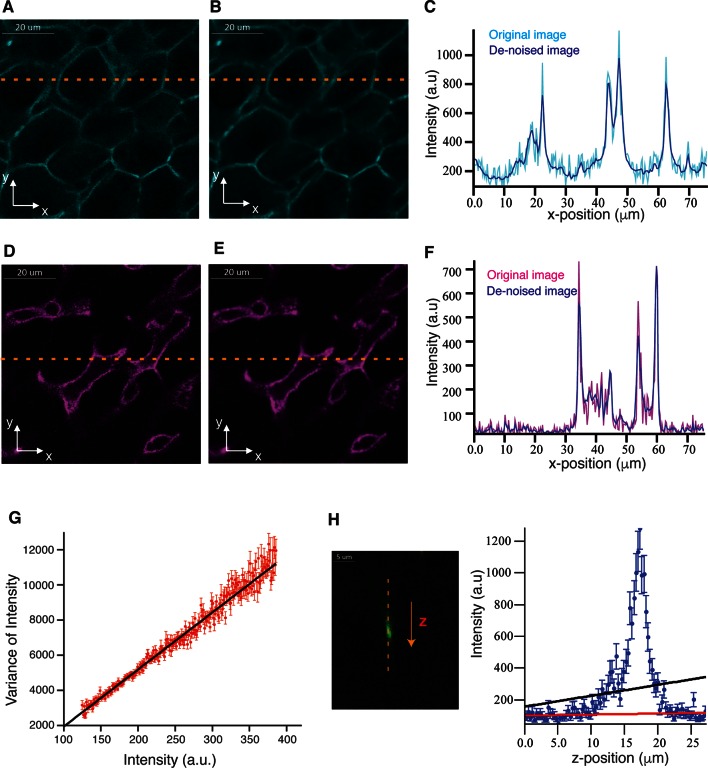

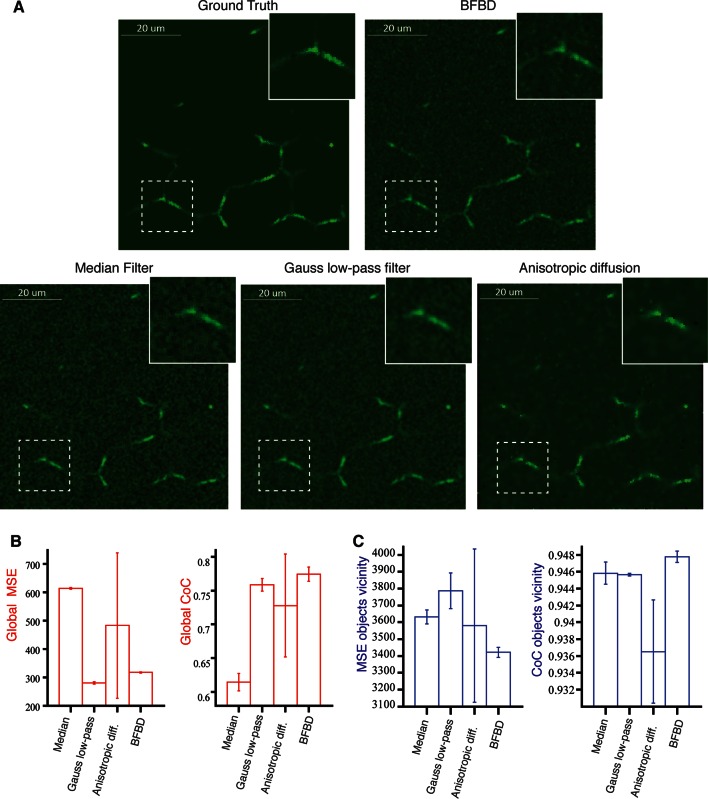

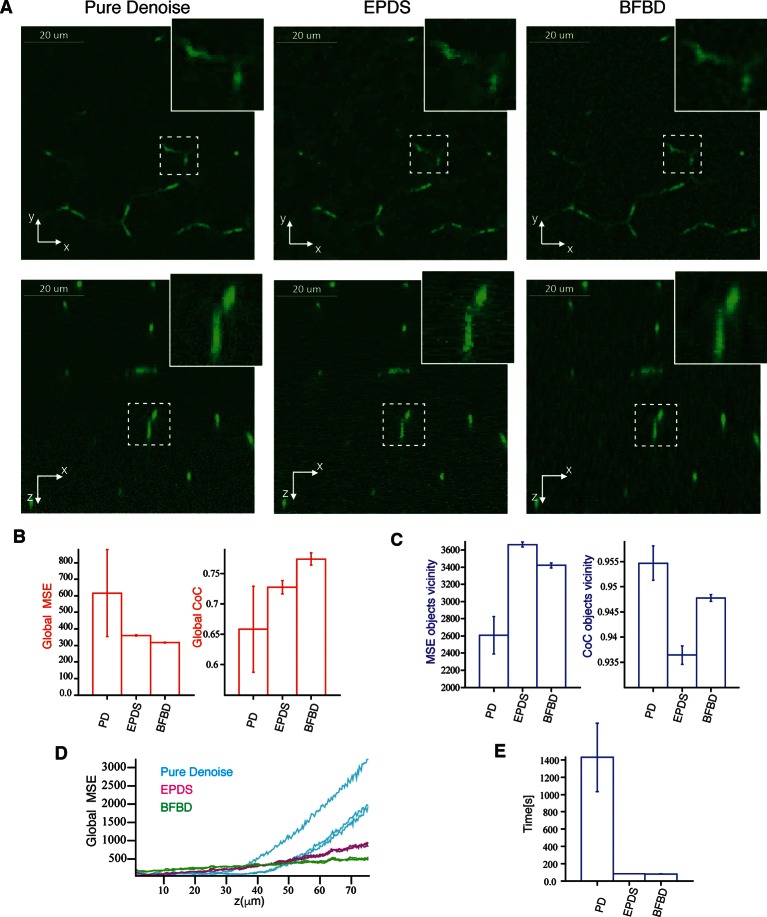

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Probabilistic image de-noising algorithm for 3D images.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Optimal parameter selection.