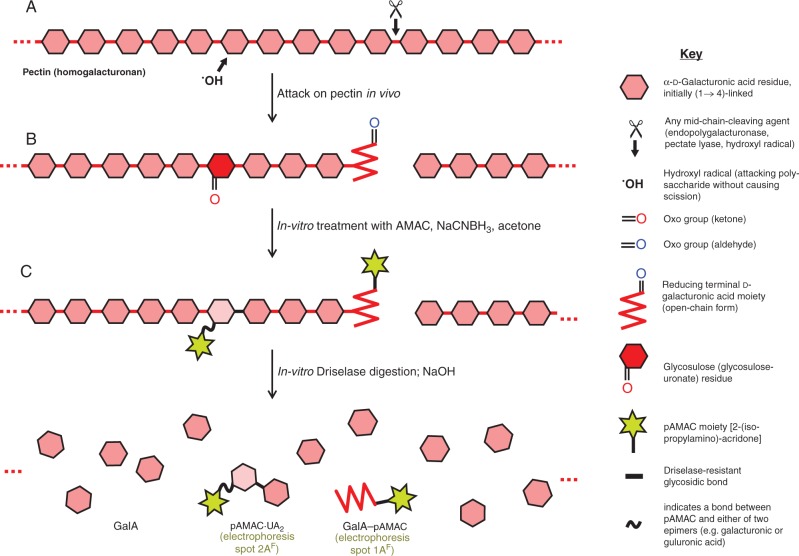

Fig. 1.

Schematic view of in-vivo attack on pectins and strategies used to detect it. (A) Part of a pectin (homogalacturonan) chain in the wall of a living fruit cell may be attacked either non-enzymically by a hydroxyl radical (•OH) or enzymically by endo-polygalacturonase or pectate lyase. Any of these three agents can cleave the backbone (e.g. at ✂), creating a new reducing terminus (shown in its non-cyclic form, and thus possessing an oxo group). In addition, •OH can non-enzymically abstract an H atom (e.g. from C-2 or C-3 of a GalA residue) without causing chain scission; in an aerobic environment, this initial reaction leads to the formation of a relatively stable glycosulose residue possessing a mid-chain oxo group. (B) Wall material (AIR) is treated in vitro with AMAC, NaCNBH3 and acetone; oxo groups are reductively aminated to form yellow–green-fluorescing pAMAC conjugates. (C) The pAMAC-labelled homogalacturonan is then digested with Driselase, which hydrolyses all glycosidic bonds except any whose sugar residue carries a pAMAC group. The products tend to lactonize and are therefore briefly de-lactonized with NaOH before being fractionated. Further details of the reactions are given in figs 1 and 2 of Vreeburg et al. (2014).