Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this study was to compare the safety and efficacy of postoperative analgesia with epidural buprenorphine and butorphanol tartrate.

Methods:

Sixty patients who were scheduled for elective laparoscopic hysterectomies were randomly enrolled in the study. At the end of the surgery, in study Group A 1 ml (0.3 mg) of buprenorphine and in Group B 1 ml (1 mg) of butorphanol tartrate both diluted to 10 ml with normal saline was injected through the epidural catheter. Visual analog pain scales (VAPSs) were assessed every hour till the 6th h, then 2nd hourly till the 12th h. To assess sedation, Ramsay sedation score was used. The total duration of postoperative analgesia was taken as the period from the time of giving epidural drug until the patients first complain of pain and the VAPS is more than 6. Patients were observed for any side effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, hypotension, bradycardia, pruritus, and headache.

Results:

Buprenorphine had a longer duration of analgesia when compared to butorphanol tartrate (586.17 ± 73.64 vs. 342.53 ± 47.42 [P < 0.001]). Nausea, vomiting (13% vs. 10%), and headache (20% vs. 13%) were more in buprenorphine group; however, sedation score and pruritus (3% vs. 6%) were found to be more with butorphanol.

Conclusion:

Epidural buprenorphine significantly reduced pain and increased the quality of analgesia with a longer duration of action and was a better alternative to butorphanol for postoperative pain relief.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, butorphanol, epidural, postoperative pain relief

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative pain is becoming a major concern because it gives rise to various physiological and psychological phenomena. Hence, effective pain control is vital for early mobilization and postoperative discharge.[1] The role of neuraxial regional techniques, particularly epidural analgesia is now well-established. When compared with conventional opioid analgesia they can provide superior analgesia, earlier mobilization, and earlier restoration of bowel function and reduced risk of postoperative respiratory and thromboembolic complications. Therefore, efforts centered on these techniques not only challenge traditional thinking but also improve the overall outcome of the patient.[2] Narcotic analgesics are frequently used in epidural anesthesia.[3] Epidural administration of μ-receptor opioid agonists such as morphine is regarded by many as the “gold-standard” single-dose neuraxial opioid due to its postoperative analgesic efficacy and prolonged duration of action. However, it is associated with troublesome side effects such as pruritus, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, and respiratory depression.[4,5] Buprenorphine is a semi-synthetic opioid with strong agonistic activity at the μ-receptor and antagonistic properties at the κ-receptor. Studies show that buprenorphine behavior is typical of μ-receptor agonists, with respect to its intended effect (potent and long-lasting analgesia) and side effects (sedation, nausea, and delayed gastric emptying), but a partial agonist at μ-receptors involved in respiratory depression.[6] Butorphanol is a lipid-soluble narcotic with strong κ-receptor agonist and weak μ-receptor agonist/antagonist activity. These have been frequently used for postoperative analgesia.[7] The analgesic efficacy of epidural buprenorphine and butorphanol is comparable to that of morphine, with less respiratory depression, pruritus, and nausea and vomiting.[8,9]

Aims

This study was made to evaluate the efficacy of epidural buprenorphine and epidural butorphanol tartrate for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Study design

Randomized, double-blinded, prospective clinical study.

METHODS

Following approval of the Ethical Committee of KVG Medical College and Hospital, Sullia and obtaining written informed consent from patients, 60 patients who belonged to the American Society of Anesthesiologists I–II, aged between 45 and 60 years scheduled for elective laparoscopic hysterectomies were randomly enrolled in the study. Patients were randomly assigned using sealed envelope technique into two groups of 30 patients each. All patients provided written consent for the surgical procedure and anesthetic method. A single anesthesiologist handled all the anesthesia procedures. All patients underwent preanesthetic evaluation on the previous day of surgery. Basic laboratory investigations such as hemoglobin, fasting blood sugar or random blood sugar, blood urea, serum creatinine, and electrocardiography (ECG) were carried out routinely in all patients. Chest radiography was carried out when indicated. All patients were premedicated with tablet anxit 0.5 mg orally the night before the procedure.

The anesthesia machine was checked before the start of the procedure. Drugs and equipments necessary for resuscitation and general anesthesia were kept ready. Routine monitors (ECG, noninvasive blood pressure [BP], and pulse oximetry) were applied in the operating room. The baseline readings were recorded.

An intravenous (IV) line was obtained with the 18-gauge cannula in all patients. Injection ondansetron 4 mg IV and injection ranitidine 50 mg IV were given. The patients were preloaded with ringer lactate 500 ml ½ h before the procedure.

The patients were placed in the left lateral position. Under all aseptic precautions, a skin wheal was raised in the L2-L3 or L3-L4 interspace with 2 ml 2% lignocaine. An 18-gauge Tuohy needle was passed through space about 1 cm. The stylet was removed, and a 10 ml loss of resistance (LOR) syringe with 5 ml of 0.9% normal saline (NS) was firmly attached to the hub of the tuohy needle. The needle was slowly advanced until it enters the epidural space, which was identified by the LOR technique. The LOR syringe was disconnected. The absence of blood or cerebrospinal fluid was verified by negative aspiration. An 18-gauge epidural catheter was passed through the epidural space with the catheter tip downward 5 cm into space. Three milliliters of 2% lignocaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 was given as test dose. Hemodynamic parameters were monitored for 5 min. Patients were put in supine position.

All patients were induced with propofol 2 mg/kg IV. Fentanyl 2 μg/kg IV was given for intraoperative analgesia and midazolam 0.05 mg/kg IV was given for sedation and intraoperative amnesia. Tracheal intubation was facilitated with succinylcholine 2 mg/kg IV. Intratracheal tube placement was confirmed by auscultation of the chest and capnography. Ryles tube was placed. Patients were put in position after giving vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg IV. Anesthesia was maintained with intermittent vecuronium 0.05 mg/kg IV, isoflurane (0.4–1.5%), nitrous oxide, and oxygen. The lungs were ventilated to maintain end-tidal carbon dioxide between 32 and 36 mm Hg. Intraoperative hypertension was treated with nitroglycerin infusion. Nitrous oxide was discontinued after the patients are fully awake. Neuromuscular reversal was achieved with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg IV and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg IV. Extubation was done in the supine position after confirming the patient's response to verbal commands.

At the end of the surgery, in study Group A, 1 ml (0.3 mg) of buprenorphine diluted to 10 ml with NS was injected through the epidural catheter. In Group B, 1 ml (1 mg) of butorphanol tartrate diluted to 10 ml with NS was injected through the epidural catheter. Patients were observed in the recovery room. Observations were recorded by a blinded observer anesthesiologist. Visual analog pain scales (VAPSs) were assessed every hour till the 6th h, then 2nd hourly till the 12th h. To assess sedation, Ramsay sedation score (RSS) was used. The pulse rate, BP, and respiration were monitored. Patients were given rescue analgesic (injection diclofenac 50 mg IV) when the patients complained of pain, and the pain scales (VAPS) were more than 6.

The total duration of postoperative analgesia was taken as the period from the time of giving epidural drug until the patients first complained of pain and the VAPS was more than 6. Patients were observed for any side effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and headache.

Definitions

Hypotension (defined as a decrease in systolic BP >30% of the baseline value or systolic BP <90 mm Hg) was treated with IV boluses of 6 mg ephedrine

Bradycardia defined as a pulse rate of <50 beat/min was treated with IV boluses of 0.3–0.6 mg atropine

Respiratory depression (respiratory rate <8 or saturation of peripheral oxygen <95%) was treated with oxygen supplementation and respiratory support if required.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of the data and application of various statistical tests was carried out with the help of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (16th version SPSS Inc., 233 South Wacker Drive, 11th Floor, Chicago, IL). Taking an alpha error 0.01 and beta error of 0.01 for the parameter (duration of analgesia),[1] the minimum sample size required to conduct the study would be 29/group. To compensate for greater variability, 30 patients were included in each group. Data were compiled, analyzed, and presented as mean, standard deviation (SD), percentages, t-test, and Mann–Whitney's test. The P value was considered significant as shown below:

P > 0.05 - Not significant

P < 0.05 - Significant

P < 0.001 - Highly significant.

RESULTS

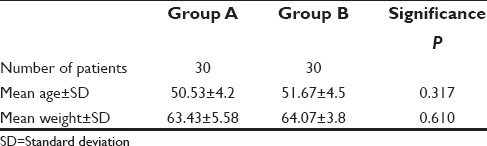

Table 1 showed that there was no difference in the age and weight (P > 0.05). Demographically, both the groups were comparable using unpaired Student's t-test. The mean duration of surgery was 152.5 ± 9.31 min.

Table 1.

Demographics

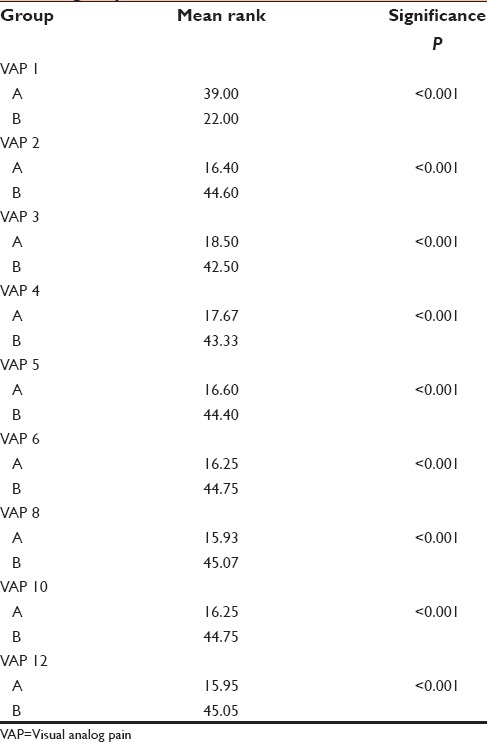

The VAPSs among both the groups were compared using Mann–Whitney's test [Table 2]. In the study Group A, the mean rank of VAPS at 1st h was significantly higher (39 vs. 22 [P < 0.001]) than study Group B. From 2nd h to 12th h, the mean rank of VAPS of the study Group B (the highest mean rank of VAPS being 45.07 at the 8th h and the lowest being 42.50 at the 3rd h) showed statistically significant increase (P < 0.001) when compared to the study Group A (the highest mean rank of VAPS being 18.50 at the 3rd h and the lowest being 15.93 at the 8th h).

Table 2.

Comparisons of visual analog pain score in both groups

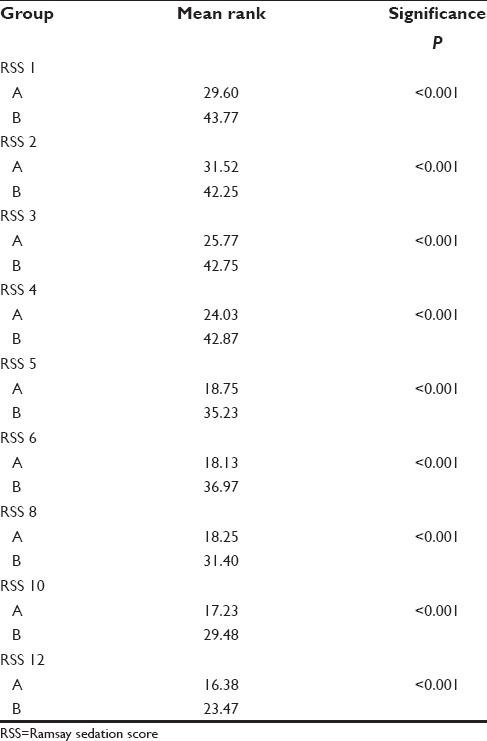

The RSS among both the groups were compared using Mann–Whitney's test. Table 3 shows that the mean score of RSS in the study Group B was significantly much higher when compared to the study Group A (P < 0.001). The maximum mean rank of sedation score in the study Group A (31.52) was during the 2nd postoperative h and in the study Group B (43.77) was during the 1st h itself. The sedation scores showed a decreasing trend and at the 12th h, the study Group A had significantly less sedation than the study Group B.

Table 3.

Comparison of Ramsay sedation score in both groups

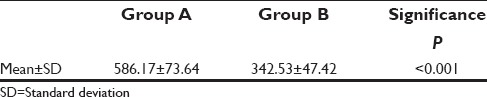

The duration of analgesia was assessed using Student's t-test. Table 4 shows there was statistically highly significant difference in duration of analgesia between the two groups (586.17 ± 73.64 vs. 342.53 ± 47.42 min [P < 0.001]).

Table 4.

Duration of analgesia in minutes

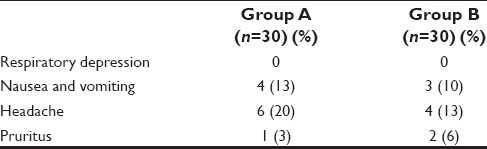

Respiratory depression was not seen in both the study groups. Nausea and vomiting occurred in four patients in the study Group A and in three patients in the study Group B. Headache occurred in six patients in the study Group A and in four patients in the study Group B. One patient in the study Group A and two patients in the study Group B also had pruritus. No other complication was observed in either group [Table 5].

Table 5.

Side effects

DISCUSSION

Postoperative pain is one of the most prevalent forms of acute pain, and it is of major medical, economic, and social concern. It is defined as a complex physiologic reaction to tissue injury or visceral distension which is subjective and results in unpleasant, unwanted sensory, and emotional experience. Effective pain control is essential for the optimal care of surgical patients, as these patients suffer from considerable pain in the postoperative period. Therefore, it has been recognized as a prime concern for anesthesiologists.[1]

Epidural route is used extensively for postoperative pain control. Cleland in 1949 was the first person to describe the technique of epidural analgesia for postoperative pain relief.[10] Epidural opioids have been administered commonly to relieve anxiety and reduce pain associated with surgery. Opioids bind to specific opioid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system and other tissues. There are three principle classes of opioid receptors, mu delta and kappa (µ, δ, and κ) receptors. The pharmacodynamic response depends upon which receptor the opioid binds, the affinity of binding and whether it is an agonist or an antagonist. For example, the analgesic properties of morphine are mediated by µ1-receptor, respiratory depression and physical dependence by µ2-receptor, and sedation by the κ-receptor.[11] A study using epidural narcotics for postoperative analgesia concluded that analgesia produced by epidural route was greater than IV route and was relatively free of side effects.

Epidural morphine for postoperative analgesia was first reported byBehar et al.[12] in 1979, and since then they are very popular. However, their side effects were undesirable which lead to a resurgence of newer drugs such as tramadol hydrochloride, fentanyl citrate, butorphanol tartrate, and buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine is a semi-synthetic opioid with partial agonist activity at the µ-receptor, partial or full agonist activity at the δ-receptor, and competitive antagonist activity at the κ-receptor. It is a powerful analgesic, approximately 25–40 times as potent as morphine.[11] It also has a long half-life with relatively little side effects. Furthermore, it is prepared in a preservative-free solution has high lipid solubility, strong affinity for opioid receptors and is, therefore, a logical choice to be used epidurally.

Butorphanol tartrate is a synthetic morphine derivative which has partial agonist and antagonist activity at the µ-receptor and agonist activity at the κ-receptor.[11] As with other opioid analgesics, central nervous system effects (sedation, confusion, and dizziness) are considerations with butorphanol.

Thus, this study was made to evaluate the efficacy of epidural buprenorphine and epidural butorphanol tartrate for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic hysterectomies.

Quality of analgesia (visual analog pain scale)

In our study, Group A showed significantly higher mean rank of VAPS at 1st h (39 vs. 22 [P < 0.001]) when compared to Group B suggesting that onset of analgesia was faster in butorphanol group. From 2nd h to 12th h, we could observe a statistically significant decrease (P < 0.001) in the mean rank of VAPS of the study Group A when compared to the study Group B showing that epidural buprenorphine significantly reduced pain and increased the quality of analgesia [Table 2].

Duration of analgesia

In our study, Table 4 shows that buprenorphine (Group A) had a longer duration of analgesia when compared to butorphanol tartrate (Group B) for postoperative epidural analgesia (586.17 ± 73.64 vs. 342.53 ± 47.42 min [P < 0.001]).

Side effects

Sedation

Sedation Score was (43.77–23.47) significantly higher with butorphanol tartrate as compared to (29.60–16.38) with buprenorphine in our study [Table 3].

Other side effect

Respiratory depression was not seen in both the study groups. Nausea, vomiting (13% vs. 10%), and headache (20% vs. 13%) was more in buprenorphine group; however, pruritus (3% vs. 6%) was found to be more with butorphanol. No other complication was observed in either of the groups.

Wolff et al. showed that the duration of action was 620 min with epidural buprenorphine (0.3 mg) while it was 580 min with 4 mg of epidural morphine for postoperative pain relief after major orthopedic surgery which was consistent with our study.[8] Agarwal et al. showed that epidural bupivacaine (0.125%) and buprenorphine (0.075 mg) produced significantly longer duration (690 ± 35 min) and better quality of postoperative analgesia in lower segment caesarean segment patients.[13] Wilde et al. did a study on 50 patients undergoing spinal decompression. Each patient was given either 0.3 mg buprenorphine in 10 ml NS or 10 ml of saline alone. Linear analog pain score for buprenorphine was 3.7 ± 2.3, whereas with NS it was 6.1 ± 2.2 (P < 0.005). Mean time before first analgesia (hours) was 10.2 ± 5.4 for buprenorphine and with NS, it was 5.3 ± 3.2 (P < 0.005).[14]

Birajdar et al. did a study and concluded that the duration of postoperative analgesia provided by 2 mg of epidural butorphanol is slightly longer than that provided by 1 mg, but the difference is statistically not significant.[15] Bharti and Chari in their study found that the duration of analgesia with 2 mg of epidural butorphanol was 4.35 ± 0.66 h which was more or less similar to our study.[16] Gupta et al. compared butorphanol (2 mg) and tramadol in their study. It was shown that the duration of analgesia was 5.35 ± 0.29 h in butorphanol group. Sedation scores were significantly higher in butorphanol group. This was consistent with our study.[17] Parikh et al. did a randomized, double-blind, prospective study on 80 patients who were undergoing thoracoabdominal and lower limb surgeries. Injection butorphanol 0.04 mg/kg in Group B (n = 40) or morphine 0.06 mg/kg in Group M (n = 40) was given in a double-blind manner after completion of surgery through the epidural catheter. The duration of pain relief after the 1st dose was statistically significant and was 339.13 ± 79.57 min in Group B and 709.75 ± 72.12 min in Group M.[9]

Venkatraman and Sandhiya conducted a study in 80 patients scheduled for elective abdominal and gynecological procedure. At the end of surgery, study group received 2 mg of butorphanol in 10 ml NS through an epidural catheter, and the control group received 10 ml of NS. Epidural butorphanol produced a duration of analgesia of 7.46 ± 1.35 h.[18]

Devulapalli and Verma study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy and safety of epidural butorphanol 2 mg diluted to 10 ml of NS in comparison with epidural morphine 2.5 mg diluted to 10 ml of NS given for relief of postoperative pain. Duration of analgesia ranged from 4 to 8 h with a mean ± SD of 5.20 ± 0.71 h in the butorphanol group. Duration of analgesia in the morphine group ranged from 10 to 24 h with a mean ± SD of 16.05 ± 3.14 h. The quality of analgesia was comparable in both groups, and the difference is statistically insignificant (P > 0.05).[19]

A study by Ackerman et al. demonstrated that epidural butorphanol and buprenorphine exhibited a low incidence of pruritus.[20] Carvalho's study proved that epidural and intrathecal opioids are associated with a very low risk of clinically significant respiratory depression.[21]

CONCLUSION

Both buprenorphine and butorphanol tartrate can be used epidurally for safe and effective postoperative analgesia. However, epidural buprenorphine significantly reduced pain and increased the quality of analgesia with a longer duration of action compared to epidural butorphanol tartrate. Epidural buprenorphine had lesser sedation, but it caused more nausea, vomiting, and headache. Pruritus was more with epidural butorphanol. Respiratory depression had not occurred in both the groups. No other complications were noted. Thus, we concluded that epidural buprenorphine was a better alternative to epidural butorphanol for providing postoperative pain relief.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Revar B, Patel V, Patel B, Padavi S. A comparison of epidural butorphanol tartrate and tramadol hydrochloride for postoperative analgesia using csea technique. Int J Res Med. 2015;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh B, Nihlani S. Postoperative analgesia: A comparative study of epidural butorphanol and epidural tramadol. J Adv Res Biol Sci. 2011;3:86–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur J, Bajwa SJ. Comparison of epidural butorphanol and fentanyl as adjuvants in the lower abdominal surgery: A randomized clinical study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:167–71. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.130687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sultan P, Gutierrez MC, Carvalho B. Neuraxial morphine and respiratory depression: Finding the right balance. Drugs. 2011;71:1807–19. doi: 10.2165/11596250-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromage PR, Camporesi EM, Durant PA, Nielsen CH. Nonrespiratory side effects of epidural morphine. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:490–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jadon A, Parida S, Chakraborty S, Panda A. Epidural naloxone to prevent buprenorphine induced PONV. Internet J Anesth. 2007;16:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosow CE. Butorphanol in perspective. Acute Care. 1988;12(Suppl 1):2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff J, Carl P, Crawford ME. Epidural buprenorphine for postoperative analgesia. A controlled comparison with epidural morphine. Anaesthesia. 1986;41:76–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb12710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh GP, Veena SR, Vora K, Parikh B, Joshi A. Comparison of epidural butorphanol versus epidural morphine in postoperative pain relief. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2014;22:371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleland JG. Continuous peridural and caudal analgesia in surgery and early ambulation. Northwest Med. 1949;48:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutstein HB, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Goodman and Gillman's. 11th ed. New York: Mcgraw Hill; 2006. pp. 279–378. Ch. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behar M, Magora F, Olshwang D, Davidson JT. Epidural morphine in treatment of pain. Lancet. 1979;1:527–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90947-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal K, Agarwal N, Agrawal V, Agarwal A, Sharma M, Agarwal K. Comparative analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine or clonidine with bupivacaine in the caesarean section. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:453–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.71046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilde GP, Whitaker AJ, Moulton A. Epidural buprenorphine for pain relief after spinal decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:448–50. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B3.3286657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birajdar SB, Gawande VA, Latti RG, Latti BR. Comparative study of different doses of epidural butorphanol for postoperative analgesia in orthopaedic patients. Int J Curr Res Rev. 2014;6:04–13. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bharti N, Chari P. Epidural butorphanol-bupivacaine analgesia for postoperative pain relief after abdominal hysterectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2009;21:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Kaur S, Singh S, Aujla KS. A comparison of epidural butorphanol and tramadol for postoperative analgesia using CSEA technique. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:35–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatraman R, Sandhiya R. Evaluation of efficacy of epidural butorphanol tartrate for postoperative analgesia. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7:52–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devulapalli PK, Verma HR. A comparative study of epidural butorphanol and epidural morphine for the relief of postoperative pain. JEMDS. 2015;4:5161–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackerman WE, Juneja MM, Kaczorowski DM, Colclough GW. A comparison of the incidence of pruritus following epidural opioid administration in the parturient. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:388–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03005335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho B. Respiratory depression after neuraxial opioids in the obstetric setting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:956–61. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318168b443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]