Abstract

Objectives

To compare the efficacy of silodosin (8 mg) vs tamsulosin (0.4 mg), as a medical expulsive therapy, in the management of distal ureteric stones (DUS) in terms of stone clearance rate and stone expulsion time.

Patients and methods

A prospective randomised study was conducted on 115 patients, aged 21–55 years, who had unilateral DUS of ⩽10 mm. Patients were divided into two groups. Group 1 received silodosin (8 mg) and Group 2 received tamsulosin (0.4 mg) daily for 1 month. The patients were followed-up by ultrasonography, plain abdominal radiograph of the kidneys, ureters and bladder, and computed tomography (in some cases).

Results

There was a significantly higher stone clearance rate of 83% in Group 1 vs 57% in Group 2 (P = 0.007). Group 1 also showed a significant advantage for stone expulsion time and analgesic use. Four patients, two in each group, discontinued the treatment in first few days due to side-effects (orthostatic hypotension). No severe complications were recorded during the treatment period. Retrograde ejaculation was recorded in nine and three patients in Groups 1 and 2, respectively.

Conclusion

Our data show that silodosin is more effective than tamsulosin in the management of DUS for stone clearance rates and stone expulsion times. A multicentre study on larger scale is needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of silodosin.

Abbreviations: DUS, distal ureteric stones; KUB, plain abdominal radiograph of the kidneys, ureters and bladder; MET, medical expulsive therapy; SWL, shockwave lithotripsy

Keywords: Silodosin, Tamsulosin, Distal, Ureteric, Stone

Introduction

Urolithiasis affects ≈12% of the population globally [1]. Ureteric stones represent ≈20% of urolithiasis cases, from which ≈70% are situated in the lower third of the ureter and termed ‘distal ureteric stones’ (DUS) [2]. Over the last two decades, the management of ureteric stones had changed greatly, especially after the introduction of shockwave lithotripsy (SWL) and ureteroscopy, as minimally invasive treatments. However, these treatments are expensive and are not risk free. The overall complications after ureteroscopy have been estimated to be 10–20% in different studies, in which major complications, such as ureteric avulsions, perforations and strictures, occurred in 35% of cases [3].

Recently, α-blockers used as medical expulsive therapy (MET) have replaced minimally invasive procedures as the first line of management for small ureteric stones [4], [5]. The clinical benefit of α-blockers for treating DUS had been shown in two meta-analysis with a high level of evidence, in which spontaneous stone passage in patients given α-blockers were 52% and 44% greater than those not given such medications [6], [7].

Both the AUA [8] and the European Association of Urology (EAU) [9] recommend α-blockers for the treatment of ureteric stones. Recently, the α1A-adrenoceptor subtype has been shown to play the major role in mediating phenylephrine-induced contraction of the human isolated ureter [10]. In the human ureter, silodosin (a selective α1-adrenoceptor blocker) was found to be more effective than an α1D-adrenoceptor blocker in noradrenaline-induced contraction [11]. However, published data are limited on the use of silodosin as MET for DUS; thus we conducted a prospective randomised study to compare the efficacy and safety of silodosin vs tamsulosin as MET for single, symptomatic, uncomplicated DUS in adults.

The objective of the present study was to compare the efficacy and safety of silodosin (8 mg) vs tamsulosin (0.4 mg) as a MET in the management of DUS in terms of stone clearance rate and stone expulsion time, and adverse effects.

Patients and methods

This prospective randomised study was conducted between March 2014 and September 2014, the cohort comprised 115 adult patients (74 men and 41 women) who presented with a symptomatic, unilateral, single, uncomplicated DUS of ⩽10 mm.

Patients were randomised 1:1, with the first case selected using a sealed envelope method. The sample size was calculated using Epi Info 6 version 6.04d program software (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland) and the difference in stone expulsion time between the two groups was considered as clinical equivalence with a confidence of 95% and power of 80%. The exclusion criteria were: a single kidney, bilateral ureteric stones, renal impairment, UTI, high-grade hydronephrosis (Grades 3 and 4 according to Society of Fetal Ultrasound, SFU), and any history of previous endoscopic or surgical interventions.

All patients were diagnosed by plain abdominal radiograph of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (KUB), ultrasonography, and non-enhanced spiral CT (in some cases). Every patient provided informed written consent after receiving information about the nature of the study, time to study end, adverse effects, and the possibility of intervention if needed. The patients were randomly divided into two groups; Group A (58 patients) received a single dose of silodosin (8 mg) daily, and Group B (57 patients) received a single dose of tamsulosin (0.4 mg) daily. For ureteric colic, diclofenac sodium (50 mg tablet) was prescribed for analgesia. We used a visual analogue scale for pain assessments.

Follow-up was performed every week by asking the patient about stone passage, attacks of renal colic, analgesic requirements, time of stone passage, and symptoms related to side-effects of the drugs. Radiological assessment was done every 2 weeks with plain KUB and ultrasonography for radio-opaque stones, and non-contrast spiral CT for radiolucent stones at the end of the study. All patients were advised to increase water intake and to filter their urine to detect stone expulsion. The primary endpoint was the rate of stone clearance and the secondary endpoint was stone expulsion time. The patients were followed-up until stone passage was confirmed by plain KUB or non-contrast spiral CT or at the end of the study period (4 weeks) and surgical intervention.

Data were checked, entered and analysed using SPSS version 20. Data were presented as the mean (SD) for quantitative variables, and number and percentage for categorical variables; the chi-squared, Fisher’s exact test or t-test were used when appropriate. The threshold level of significance was fixed at 5% for all the above mentioned tests. The results were considered:

-

•

Significant when the probability of error is <5% (P < 0.05).

-

•

Non-significant when the probability of error is >5% (P > 0.05).

-

•

Highly significant when the probability of error is <0.1% (P < 0.001).

Our study protocol was approved by the Hospital Research and Ethics Committee, and all patients provided an informed written consent for participation.

Results

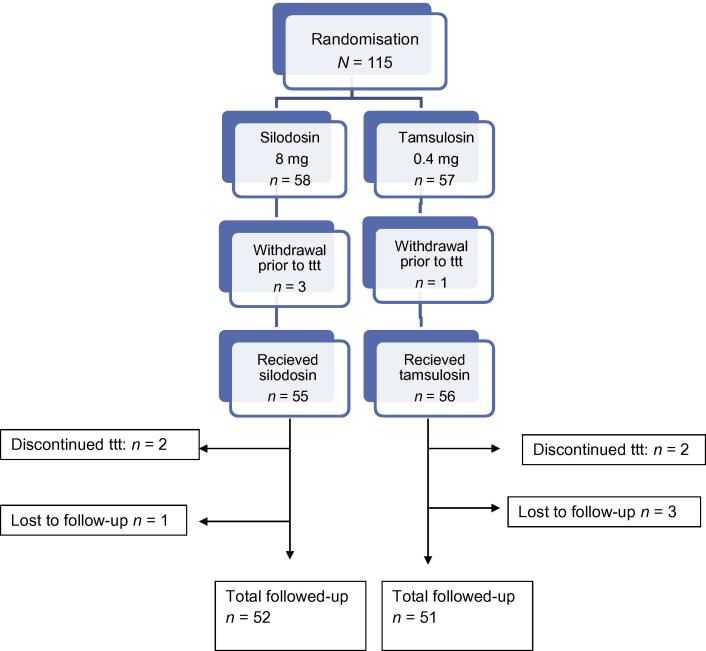

The patients’ ages in both groups ranged between 21 and 55 years. Three patients in group A and one patient in group B withdrew before treatment because of either spontaneous stone passage (one patient) or voluntary withdrawal (three). Four patients (two in each group) discontinued the treatment in the first few days due to orthostatic hypotension and were excluded from the study. During follow-up, four patients were lost (one in group A and three in group B). Thus the total number of patients analysed was 52 in Group A and 51 in Group B (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study design. ttt, treat-to-target.

There were no significant differences among the two groups for patient’s age, gender, stone laterality, and stone size (Table 1).

Table 1.

The patients’ demographic and stone data.

| Variable | Group A (silodosin 8 mg) | Group B (tamsulosin 0.4 mg) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD; range) age, years | 33.6 (9.9; 21–53) | 35.5 (11.3; 24–55) | 0.3⁎ |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Men | 35 (67.3) | 32 (62.7) | 0.7† |

| Women | 17 (32.6) | 19 (37.2) | 0.7† |

| Mean (SD) stone size, mm | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.6 (1.2) | 0.4⁎ |

| Stone side: right/left, n | 32/20 | 28/23 | 0.6† |

t-Test.

Chi-squared test.

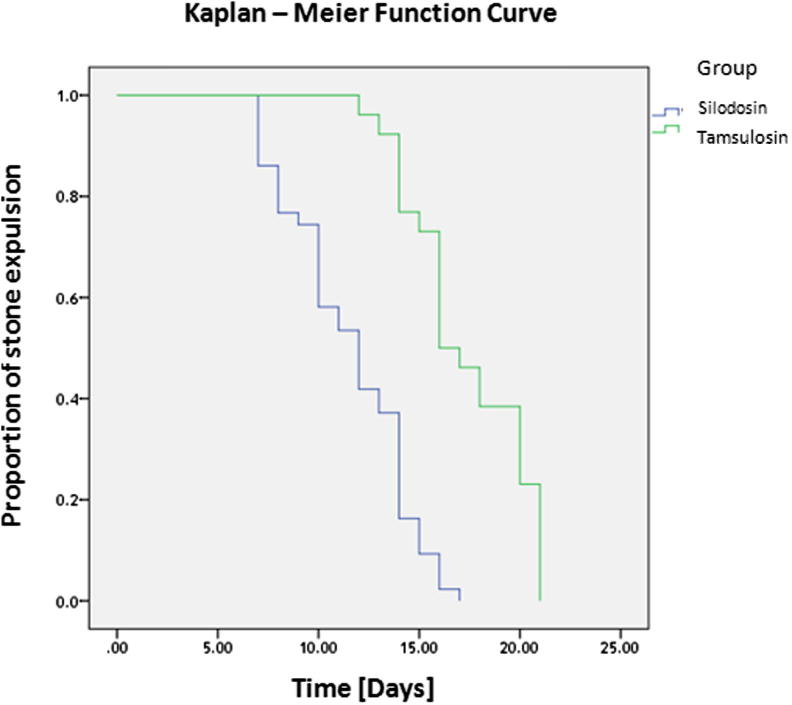

The stone clearance rate was significantly different between the groups, at 83% (43/52 patients) in Group A vs 57% (29/51 patients) in Group B (P = 0.007). In Group A (silodosin), the stone expulsion time was also significantly shorter than in Group B (tamsulosin), at a mean (SD) of 13.3 (4.1) vs 16.7 (5.4) days, respectively (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). Also, there were fewer ureteric colic episodes and less analgesic requirement in Group A (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier function curve.

Table 2.

Study outcomes.

| Outcome | Group A (silodosin 8 mg) | Group B (tamsulosin 0.4 mg) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stone clearance rate (primary endpoint), n (%) | 43 (83) | 29 (57) | 0.007† |

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Stone expulsion time (secondary endpoint), days | 13.3 (4.1) | 16.7 (5.2) | <0.001⁎ |

| Visual analogue scale score | 2.2 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.4) | 0.07⁎ |

| Pain episodes, n | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.3) | 0.15⁎ |

| Analgesic use: diclofenac sodium, mg | 239 (12.2) | 243 (11.9) | 0.09⁎ |

t-Test.

Chi-squared test.

Orthostatic hypotension was encountered in two patients (3.8%) in Group A, who discontinued treatment, and four patients (7.8%) in Group B, of which two patients discontinued treatment. Abnormal ejaculation was recorded in nine patients (17.3%) in Group A (silodosin) and in three patients (5.9%) in Group B (tamsulosin), which was statistically nonsignificant; however, no patient discontinued the study, as they were informed about this adverse effect and that it was a reversible condition.

Discussion

Ureteroscopy and SWL remain the most effective treatments for DUS; however, they are expensive and not risk free. Spontaneous stone expulsion can occur in up to 50% of cases, nevertheless, many complications such as ureteric colic, UTI, and hydronephrosis, may occur. Recently, the use of various adjuvant medications as MET for DUS has helped to reduce pain, complications, and increase the rate of stone clearance [12], [13].

The α1A- and α1D-adrenoceptors are the most abundant subtypes in the distal ureter, stimulation of these α1-adrenoceptors leads to increases in both the frequency of ureteric peristalsis and the force of ureteric contractions. However, blockade of these receptors decreases basal ureteric tone, decreases peristaltic frequency and amplitude, leading to a decrease in intra-luminal pressure while the rate of urine transport increases, and thus increasing the chance of stone passage [14].

Highly selective α1A-adrenoceptor blockers have been developed to minimise the cardiovascular adverse effects while maintaining their efficacy on the urinary tract [15]. Tamsulosin is a selective α1-blocker with a 10-fold greater affinity for the α1A- and α1D-adrenoceptor subtypes than for the α1B-adrenoceptor subtype, while the affinity of silodosin for the α1A-adrenoceptor subtype is ≈162- and 50-fold greater than its affinity for the α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptor subtypes respectively, which explain the weak cardiovascular adverse effects of silodosin [15].

In patients presenting with DUS of ⩽10 mm without the use of MET, the reported spontaneous stone clearance rates are between 35.2% and 61%, with mean expulsion times ranging between 9.87 and 24.5 days [16], [17], [18], [19]. Several factors can affect spontaneous stone clearance of DUS including: stone size, site, number, and also the presence or absence of ureteric smooth muscle spasm and/or submucosal oedema. Coll et al. [20], found a direct relationship between stone size and spontaneous clearance.

In our present study, the stone clearance rate was significantly higher in the silodosin group compared with the tamsulosin group, at 83% and 57%, respectively (P = 0.007). Our results are in agreement with those of Gupta et al. [21], who reported stone clearance rates of 82% and 58% for their silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively; and also in agreement with those of Kumar et al. [22], who reported stone clearance rates of 83.3% and 64.4% for their silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively. However, Imperatore et al. [23] reported a nonsignificant difference of stone clearance rates between silodosin (88%) and tamsulosin (84%). While Sur et al. [24] reported a stone clearance rate of 52% with silodosin treatment of all ureteric stones (upper, middle and lower), which may reduce the overall efficacy as α-receptors are more abundant in the distal ureter.

The mean (SD) stone expulsion time was significantly shorter in the silodosin group vs the tamsulosin group, at 13.3 (4.1) vs 16.7 (5.2) days, respectively (P < 0.001). These results are also in agreement with those of Gupta et al. [21], who also reported significantly shorter mean (SD) stone expulsion times in the silodosin vs the tamsulosin group, at 12.5 (3.5) vs 19.5 (7.5) days, respectively; and also in agreement with Kumar et al. [22] who reported mean (SD) stone expulsion times of 16.5 (4.6) days in the tamsulosin group and 14.8 (3.3) days in the silodosin group. However, Imperatore et al. [23] reported a shorter mean stone expulsion time for both silodosin and tamsulosin of 6.7 and 6.5 days, respectively.

For safety issues and adverse effects, both drugs are safe and well tolerated, and the most frequently encountered side-effect in the present study was retrograde ejaculation, which was reported in nine (17.3%) and three patients (5.9%) in the silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively, which was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.135). However, no patient discontinued the treatment because of retrograde ejaculation and the condition was reversible, resolving within a few days of cessation of treatment. However, Imperatore et al. [23] reported that retrograde ejaculation was significantly different between silodosin (2%) and tamsulosin (8%). In the present study, six patients had orthostatic hypotension, two in the silodosin group (3.8%) and four in the tamsulosin group (7.8%), which was not statistically significantly different. These results are in agreement with those of Kumar et al. [22], who reported orthostatic hypotension in 3.3% and 6.6% in the silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively; and also in agreement with Imperatore et al. [23] who reported a nonsignificant difference in orthostatic hypotension of 2% and 6% in the silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively. However, only four patients in our present study discontinued treatment (two in each group) and were excluded from the study, while two patients in the tamsulosin group with orthostatic hypotension completed the treatment course.

The results from the present study show a low mean (SD) number of pain episodes in both groups of 1.3 (0.4) and 1.4 (0.3) in the silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively, which was not statistically significantly different (P = 0.15). These results were in agreement with Kumar et al. [22], who reported a mean (SD) number of pain episodes of 0.8 (0.9) and 1.70 (1.2) in the silodosin and tamsulosin groups, respectively; and also in agreement with Imperatore et al. [23] who reported a nonsignificant difference between the silodosin and tamsulosin groups of 1.6 (0–4) and 1.7 (0–4), respectively. The pain relieving effects of the α-blockers may be explained by the blocking of C-fibres responsible for mediating pain [25].

In conclusion, silodosin is more effective than tamsulosin in the management of DUS for the stone clearance rate and stone expulsion time; however, a multicentre study on a larger scale is needed to confirm its efficacy and safety.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Source of Funding

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- 1.Curhan G.C. Epidemiology of stone disease. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erturhan S., Erbagci A., Yagci F., Celik M., Solakhan M., Sarica K. Comparative evaluation of efficacy of use of tamsulosin and/or tolterodine for medical treatment of distal ureteral stones. Urology. 2007;69:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segura J.W., Preminger G.M., Assimos D.G., Dretler S.P., Kahn R.I., Lingeman J.E. Ureteral stones clinical guidelines panel summary report on the management of ureteral calculi. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997;158:1915–1921. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervenakov I., Fillo J., Mardiak J., Kopecny M., Smirala J., Lepies P. Speedy elimination of ureterolithiasis in lower part of ureters with the alpha1-blocker-Tamsulosin. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;34:25–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1021368325512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tzortzis V., Mamoulakis C., Rioja J., Gravas S., Michel M.C., de la Rosette J.J. Medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral stones. Drugs. 2009;69:677–692. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollingsworth J.M., Rogers M.A., Kaufman S.R., Bradford T.J., Saint S., Wei J.T. Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:1171–1179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons J.K., Hergan L.A., Sakamoto K., Lakin C. Efficacy of alpha-blockers for the treatment of ureteral stones. J Urol. 2007;177:983–987. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Urological Association. Ureteral Calculi: 2007 Guideline for the Management of Ureteral Calculi, EAU/AUA Nephrolithiasis Panel. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Ureteral-Calculi.pdf; 2007 [accessed January 2014].

- 9.Tiselius H.G., Ackermann D., Alken P., Buck C., Conort P., Gallucci M. Guidelines on urolithiasis. Eur Urol. 2001;40:362–371. doi: 10.1159/000049803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki S., Tomiyama Y., Kobayashi S., Kojima Y., Kubota Y., Kohri K. Characterization of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes mediating contraction in human isolated ureters. Urology. 2011;77 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.09.034. 762.e13-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi S., Tomiyama Y., Hoyano Y., Yamazaki Y., Kusama H., Itoh Y. Gene expressions and mechanical functions of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes in mouse ureter. World J Urol. 2009;27:775–780. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0396-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porpiglia F., Destefanis P., Fiori C., Fontana D. Effectiveness of nifedipine and deflazacort in the management of distal ureter stones. Urology. 2000;56:579–583. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00732-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellabella M., Milanese G., Muzzonigro G. Randomized trial of the efficacy of tamsulosin, nifedipine and phloroglucinol in medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2005;174:167–172. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161600.54732.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griwan M.S., Singh S.K., Paul H., Pawar D.S., Verma M. The efficacy of tamsulosin in lower ureteral calculi. Urol Ann. 2010;2:63–66. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.65110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossi M., Roumeguère T. Silodosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2010;27(4):291–297. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S10428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed A.F., Al-Sayed A.Y. Tamsulosin versus alfuzosin in the treatment of patients with distal ureteral stones: prospective, randomized, comparative study. Korean J Urol. 2010;51:193–197. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yilmaz E., Batislam E., Basar M.M., Tuglu D., Ferhat M., Basar H. The comparison and efficacy of 3 different alpha1-adrenergic blockers for distal ureteral stones. J Urol. 2005;173:2010–2012. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000158453.60029.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Ansari A., Al-Naimi A., Alobaidy A., Assadiq K., Azmi M.D., Shokeir A.A. Efficacy of tamsulosin in the management of lower ureteral stones: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of 100 patients. Urology. 2010;75:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agrawal M., Gupta M., Gupta A., Agrawal A., Sarkari A., Lavania P. Prospective randomized trial comparing efficacy of alfuzosin and tamsulosin in management of lower ureteral stones. Urology. 2009;73:706–709. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coll D.M., Varanelli M.J., Smith R.C. Relationship of spontaneous passage of ureteral calculi to stone size and location as revealed by unenhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178 doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.1.1780101. 101e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta S., Lodh B., Singh A.K., Somarendra K., Meitei K.S., Singh S.R. Comparing the efficacy of tamsulosin and silodosin in the medical expulsion therapy for ureteral calculi. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1672–1674. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6141.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S., Jayant K., Agrawal M.M., Singh S.K., Agrwal S., Parmar K.M. Role of tamsulosin, tadalafil, and silodosin as the medical expulsive therapy in lower ureteric stone: a randomized trial (a pilot study) Urology. 2015;85:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imperatore V., Fusco F., Creta M., Di Meo S., Buonopane R., Longo N. Medical expulsive therapy for distal ureteric stones: tamsulosin versus silodosin. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2014;86:103–107. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2014.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sur R.L., Shore N., L’Esperance J., Knudsen B., Gupta M., Olsen S. Silodosin to facilitate passage of ureteral stones: a multi-institutional, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2015;67:959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinnman E., Nygårds E.B., Hansson P. Peripheral alpha-adrenoceptors are involved in the development of capsaicin induced ongoing and stimulus evoked pain in human. Pain. 1997;69:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]